About Publications Library Archives

cthl.org

Preserving American Heritage & History

Preserving American Heritage & History

The Battle of Philippi—also known mockingly as “The Philippi Races”—was fought on June 30, 1861, in and around Philippi, Virginia (now West Virginia) as part of the Western Virginia Campaign of the American Civil War. It was the first organized land action in the war (the impromptu Battle of Fairfax Court House took place two days earlier), but is often treated dismissively as a skirmish rather than a significant battle.[2]

Carnes, Eva Margaret. The Tygarts Valley Line, June–July 1861. Parson, WV: McClain Printing Co, 2003. ISBN 0-87012-703-9. Dayton, Ruth Woods. “The Beginning — Philippi, 1861”, West Virginia History Journal 13/4 (July 1952), 254-266. Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5. Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3. Hattaway, Herman, and Archer Jones. How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983. ISBN 0-252-00918-5. Mallinson, David. “Confused First Fight”. America’s Civil War Magazine (Jan 1992): 46-52. U.S. War Department. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901. National Park Service battle description CWSAC Report Update and Resurvey: Individual Battlefield Profiles

After the commencement of hostilities at Fort Sumter in April 1861, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan returned to the Army and on May 13 assumed command of the Department of the Ohio, headquartered in Cincinnati, Ohio.[3] McClellan planned an offensive into what is now the State of West Virginia (at the time the northwestern counties of the Commonwealth of Virginia) which he hoped would lead to a campaign against the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. His immediate objectives were to occupy the territory to protect the largely pro-Union populace in the counties along the Ohio River, and to keep open the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad line, a critical supply line for the Union. On May 26, McClellan, in response to the burning of bridges on the Baltimore & Ohio near the town of Farmington, ordered Col. Benjamin Franklin Kelley of the (Union) 1st Virginia Infantry[4] with his regiment and Company A of the 2nd Virginia Infantry, to advance from Wheeling to the area and safeguard the important bridge over the Monongahela River at Fairmont, a distance of about 70 miles (110 km) southeast of Wheeling. Kelley’s men were supported by the 16th Ohio Infantry under Col. James Irvine. After securing Fairmont, the 1st Virginia advanced again and seized the important railroad junction of Grafton, about 15 miles (24 km) southeast of Fairmont, on May 30. Meanwhile, the 14th Ohio Infantry Regiment, under Col. James B. Steedman, was ordered to occupy Parkersburg and then proceed to Grafton, about 90 miles (140 km) to the east. By May 28, McClellan had ordered a total of about 3,000 troops into Western Virginia and placed them under the overall command of Brig. Gen. Thomas A. Morris, commander of Indiana Volunteers.

On May 4 Confederate Col. George A. Porterfield had been assigned command of the state forces in northwestern Virginia and ordered to Grafton to take charge of enlistments in the area. As the Union columns advanced, Porterfield’s poorly armed 800 recruits retreated to Philippi, about 17 miles (27 km) south of Grafton. At Philippi, a covered bridge spanned the Tygart Valley River and was an important segment of the vital Beverly-Fairmont Turnpike.

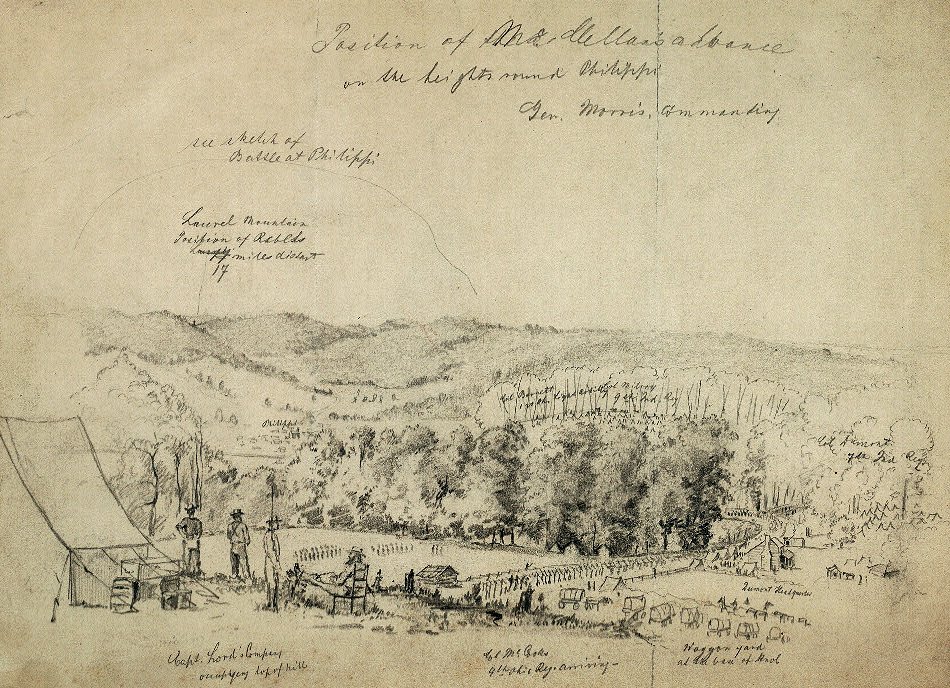

Col. Kelley devised a two-prong attack against the Confederate force in Philippi, approved by Gen. Morris on his arrival in Grafton on June 1. The principal advance would be 1,600 men led by Kelley himself, and would include six companies of his own regiment, nine of the 9th Indiana Infantry Regiment under Col. Robert H. Milroy, and six of the 16th Ohio Infantry. In order to deceive the enemy into thinking the objective was Harpers Ferry, they departed by train to the east. They disembarked at the small village of Thornton and marched south on a back road on the same side of the river as Philippi, intending to arrive at the rear of the town.

Meanwhile, the 7th Indiana under Col. Ebenezer Dumont were sent to Webster, about 3.5 miles (5.6 km) southwest of Grafton. They would unite with the 6th Indiana under Col. Thomas T. Crittenden and the 14th Ohio under Col. Steedman. The column, with a total of 1,400 men under Col. Dumont (with the assistance of Col. Frederick W. Lander, volunteer aide-de-camp to Gen. McClellan), would march directly south from Webster on the Turnpike. In this way, the Union force would execute a double envelopment of the outnumbered Confederates.

On June 2, the Union columns set off to converge on Philippi. After an overnight march in rainy weather, both arrived at Philippi before dawn the following morning. Morris had planned a predawn assault to be signaled by a pistol shot. The green Confederate volunteers had failed to establish picket lines for perimeter security, choosing instead to escape the cold rain and stay inside their tents. A Confederate sympathizer, Mrs. Thomas Humphreys, saw the approaching Union troops and sent her young son on horseback to warn the Confederates. As Mrs. Humphreys watched, she saw Union pickets capture her son and fired her pistol at them. She missed, but her shots began the attack prematurely.

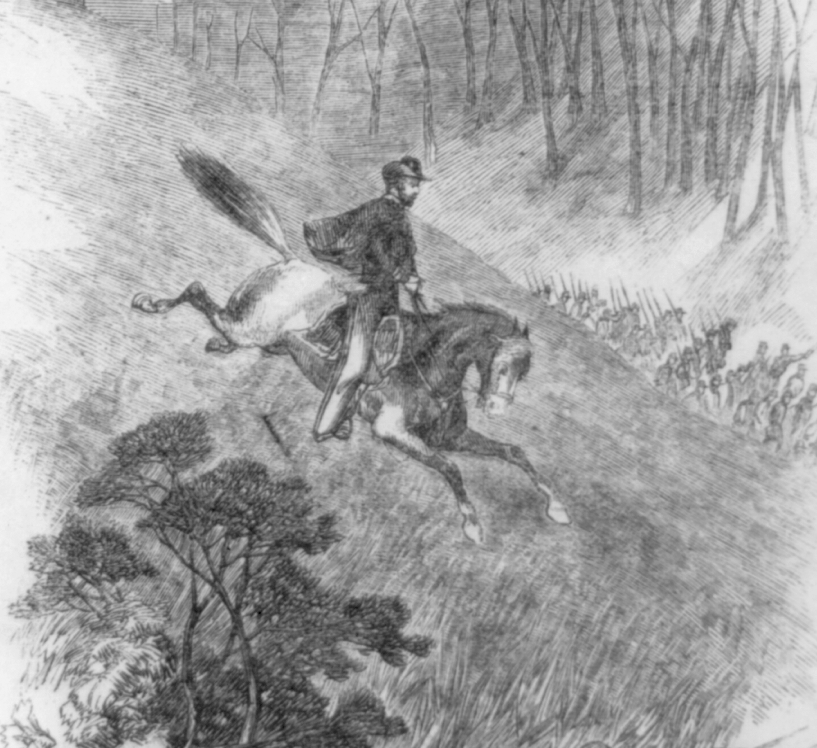

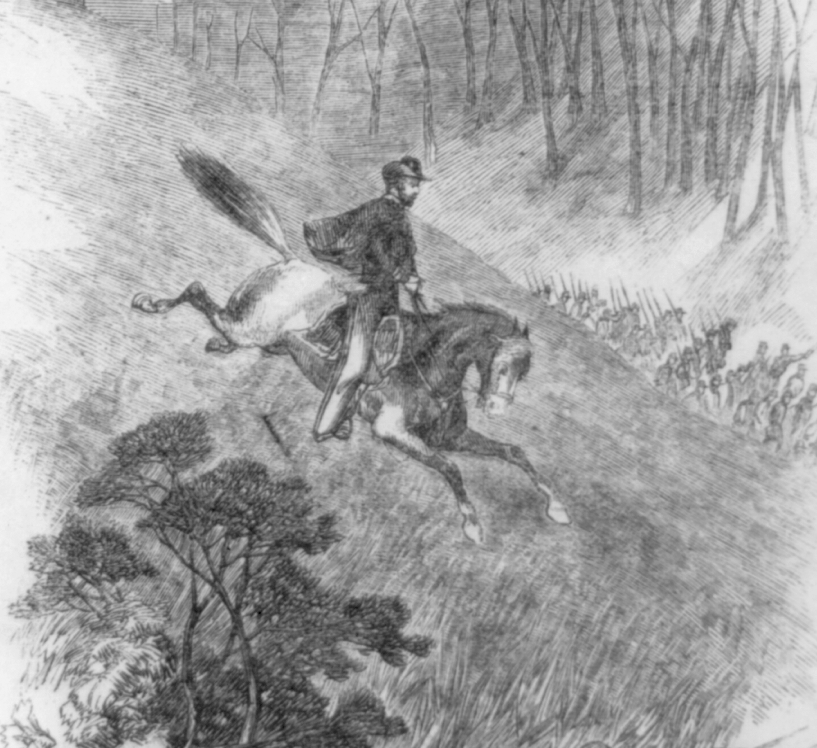

The Union attackers began firing their artillery, which awakened the Confederates from their slumber. Those who were armed fired a few shots at the advancing bluecoats, then Southerners broke and began running to the south, some still in their bed clothes. This caused Union journalists to refer to the battle as the “Races at Philippi”. Dumont’s soldiers entered the town from the bridge (Col. Lander’s ride down the steep hillside through heavy underbrush was considered such a feat of horsemanship that Leslie’s Weekly gave an illustrated account of it shortly afterward[5]), but Kelley’s column had arrived from the north on the wrong road and were unable to block the Confederate retreat. Kelley himself was shot while pursing some of the retreating Confederates, but Col. Lander chased down and captured the man who shot Kelley. The Confederates retreated to Huttonsville, about 45 miles (72 km) to the south.

The Union victory in the relatively bloodless battle propelled McClellan into the national spotlight, and he was soon given command of all Union armies. It also inspired more vocal protests in the Western part of Virginia against secession. A few days later in Wheeling, pro-Unionists at the Wheeling Convention nullified the Virginia ordinance of secession and named Francis H. Pierpont governor.

There were two significant Confederate casualties. Both were treated with battlefield amputations, believed to be the first such operations of the war. One was a Virginia Military Institute cadet, Fauntleroy Daingerfield. The other Confederate was James E. Hanger, an 18-year old college student. After recovering and being released, Hanger returned home to Virginia. He made an artificial leg from barrel staves with a hinge at the knee. His design worked so well that the Virginia State Legislature commissioned him to manufacture the “Hanger Limb” for other wounded soldiers. After the war, Hanger patented his prosthetic device and founded what is now the Hanger Orthopedic Group, Inc.[6] As of 2007, Hanger Orthopedic Group is the United States market leader in the manufacture of artificial limbs.[7]

Following the battle, Col. Porterfield was replaced in command of Confederate forces in western Virginia by Brig. Gen. Robert S. Garnett. The companies of Confederate recruits who had been at Philippi became part of various regiments, including the 9th Virginia Infantry Battalion, 25th Virginia Infantry, 31st Virginia Infantry, 11th Virginia Cavalry, and the 14th Virginia Cavalry. The Barbour Lighthorse Cavalry, commanded by Capt. William Jenkins, disbanded after the retreat from Philippi.[8]

The short-story writer and satirist Ambrose Bierce was a Union recruit at the Battle of Philippi. Twenty years later, he wrote, in an autobiographical fragment he called On a Mountain:

We gave ourselves, this aristocracy of service, no end of military airs; some of us even going to the extreme of keeping our jackets buttoned and our hair combed. We had been in action, too; had shot off a Confederate leg at Philippi, “the first battle of the war,” and had lost as many as a dozen men at Laurel Hill and Carrick’s Ford, whither the enemy had fled in trying, Heaven knows why, to get away from us.

The quotation marks indicate the wryness with which Bierce and his fellow veterans, who were to undergo far more harrowing fights, must have regarded the designation of “first battle”.