About Publications Library Archives

cthl.org

Preserving American Heritage & History

Preserving American Heritage & History

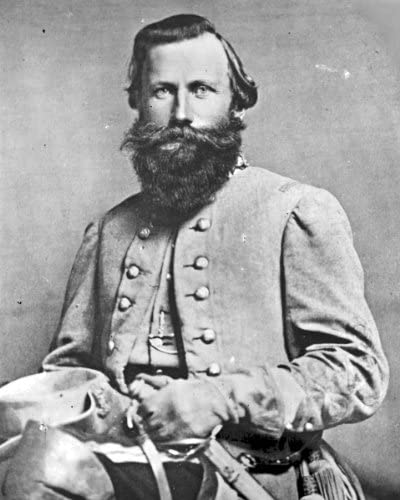

Born on February 6, 1833, James Ewell Brown (“Jeb”) Stuart was one of the more colorful cavaliers in the Army of Northern Virginia. Stuart enrolled at the the US Military Academy at West Point and graduated in 1854. His first service was the 1st US Cavalry in the Kansas territory, though he was transferred east in 1859. As a lieutenant, Stuart was with the US Army force that marched to Harper’s Ferry to put down the bloody revolt begun by John Brown, a violent abolitionist. When the Civil War broke out, Stuart resigned his commission with the United States Army and offered his services to Virginia. He was given the rank of colonel of the 1st Virginia Cavalry and assigned to the Shenandoah Valley.

Stuart’s wartime career was marked by spectacular exploits that made good news articles for Virginia newspapers. Stuart made a name for himself at the first Battle of Bull Run where his troopers swept down on retreating Union soldiers. He was promoted to brigadier general in September, 1861, and given a brigade of cavalry to command in the Army of Northern Virginia. During the Peninsula Campaign Seven Days Battles near Richmond, Stuart and his command succeeded in riding all the way around the Union Army. His ride became the subject of many news stories and a song called “Riding A Raid”. In July, 1862, General Stuart became a major general and was assigned to command the cavalry force in Lee’s army.

The general loved parties and gloried in being the center of attention. At every opportunity his staff would arrange dances and parties at homes that they decorated with flowers, ribbons, and crossed sabers. His camp attracted many officers who modeled themselves after the dashing Stuart. The general wore a plumed hat and fancy jackets adorned with brass buttons and gold lace trim. Many of his officers dressed in a similar fashion after their commander. Stuart also loved songs, poems, and a good joke, some of which he played on his infantry commander, “Stonewall” Jackson. The two officers worked extremely well as a team and Stuart used his cavalry to not only scout for Lee’s army, but to strike at Union supply lines and outposts at will. As the war carried on, Stuart’s adventures became famous in the North as well. Few Union officers were comparable in the use of mounted troopers.

Even his most ardent admirers had a difficult time defending the general’s actions during the Gettysburg Campaign. General Lee’s orders to Stuart gave the cavalryman some leeway, so he took advantage of a confused situation to raid Union supply lines and ride northeast around the Army of the Potomac into Pennsylvania. This happened while Lee moved his Army of Northern Virginia up the Shenandoah Valley and into Maryland and Pennsylvania. Separated by about 80 miles, Lee had no way of telling where Stuart was. Nor could Stuart use his cavalry to be Lee’s “eyes and ears” to inform him of where the Union army was. General Stuart did not arrive at Lee’s headquarters until long after the Battle of Gettysburg had opened, and Lee openly expressed his displeasure at Stuart for riding off and not keeping in contact with the army.

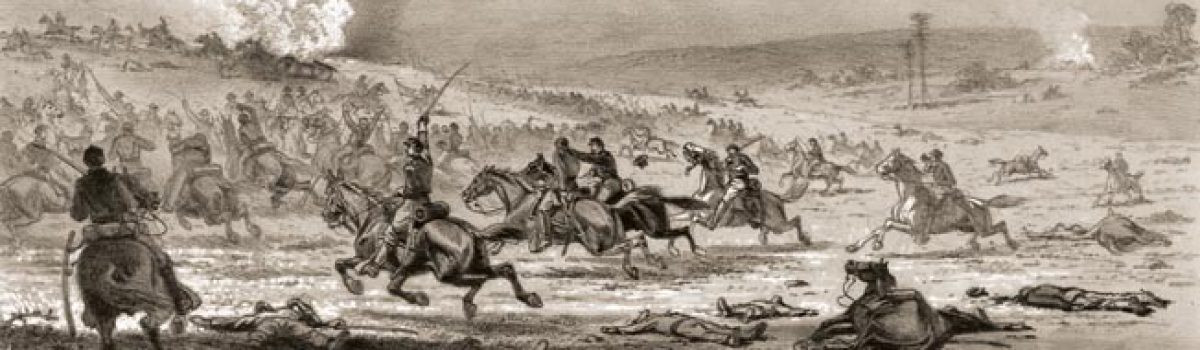

On July 3rd, General Stuart moved his cavalry division eastward to attempt to get around the Union right flank and raid the Union army’s supply lines. He was stopped and defeated in a pitched battle with Union cavalry three miles east of Gettysburg that afternoon. General Stuart’s troopers covered the army’s retreat back to Virginia and despite the controversy of his actions, Stuart was able to recover his reputation over the next six months.

When the spring of 1864 arrived, General Stuart found himself facing a new Union cavalry commander, General Philip H. Sheridan. Sheridan was ordered by General Grant to lead a raid upon Richmond while the Union army fought Lee’s army in the Battle of the Wilderness that May. On May 11, Stuart’s forces intercepted Sheridan at Yellow Tavern in front of Richmond and the gallant cavalier was mortally wounded. Taken to a hospital in Richmond, Jeb Stuart died the next day. He is buried in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond. His passing marked a turn of fortunes for the Confederate cavalry of Lee’s army, and he is still admired today as one of the greatest cavalry commanders of the Civil War.

JEB Stuart rode around Hooker’s, then Meade’s, army on the 28th and 29th of June, 1863, operating under specific instructions received in a letter dated June 23 from General Lee. The letter, written in the hand of Walter Taylor, one of Lee’s aides, is recorded at page 23 of the Gettysburg Letterbook. Lee’s instructions were:

“You will be able to judge whether you can move around their army without hindrance, doing all the damage you can and cross the river east of the mountains. . . after crossing the river you must move on and feel the right of Ewell (Early at York), collecting information, provisions, etc.”

Stuart followed Lee’s instructions fairly well. With three cavalry brigades (Fitz Lee’s, Rooney Lee’s, and Wade Hampton’s), he crossed the Potomac the night of the 27th near Dranesville, passed through Rockville early on the morning of the 28th, capturing there a 125 wagon supply train heading for the Union army, and moved north toward Westminister, Meade’s selected base of operations, destroying telegraph lines. This forced Washington to communicate with Meade by courier, delaying considerably the time in which intelligence of rebel movements reached Meade’s headquarters at Middleburg. At Hood’s Mill, Stuart sent his brigades east and west along the line of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, destroying bridges. The night of the 28th, he scouted west, encountering the movement of the Union 2nd and 5th corps which were heading northeast toward Westminister and Union Mills. The morning of the 29th, Stuart entered Westminister, skirmishing with a Union cavalry detachment, scattering it and chasing it some distance toward Baltimore. Stuart spent the night of the 29th at Union Mills, with the Union 5th and 6th corps approaching. The morning of the 30th, after waiting for Kilpatrick’s cavalry division to pass his front in the direction of Hanover, Stuart followed and struck Kilpatrick’s rear in the streets of Hanover, diverting Kilpatrick from the purpose of his mission, locating the whereabouts of the rebel force known to be at York and Wrightsville. Breaking off the engagement in the afternoon, Stuart, with his captured train and prisoners, passed around York and headed northwest through Dover and Dillsburg, reaching Carlisle on July 1.

Though Stuart did not actually open direct communication with Early’s division, he certainly “felt” Early’s presence, which explains his attack on Kilpatrick’s rear. Stuart knew that Early was at York on the 29th, that he would be moving west to join Ewell, as that was Lee’s plan as explained to him when he met with Lee at Paris, Fauquier County, on June 22. Indeed, White’s cavalry, operating with Early, had been to Hanover, burning railroad bridges, on the 29th, and Stuart’s pickets and scouts certainly came very close to contacting Early’s cavalry squadrons that were roaming the country around Hanover.

As explained in The Gettysburg Letterbook, the controversy that developed over Stuart’s ride around Hooker was created, in large measure, by Charles Marshall, aide de camp to Lee, who claimed responsibility for drafting the text of Lee’s “official” Jan 1863 operations report. In the report, Lee constructed a story to support his public position that, when he entered Pennsylvania, he did not intend to draw the Union army into a general battle at Gettysburg; instead, the report says, he intended to move on Harrisburg, by way of Carlisle and the Wrightsville bridge, but, because he was operating without the benefit of reconnaissance reports from Stuart, he was forced by circumstance (the illusory threat of the Union army moving west of South Mountain) to move his army east of the mountains, which brought it “unexpectedly” upon Meade’s advance at Gettysburg. After the war was over, Marshall pushed this story in an address he made on the occasion of Lee’s birthday in 1896, and it was repeated by Frederick Maurice in the book, Charles Marshall, Aide de Camp to General Lee, published in 1925. It has been adopted by most civil war writers without questioning either Marshall’s credibility, or his veracity. In fact, Lee knew all he needed to know of the movement of the Union army, during June 27-July1, based upon the paramount principle of concentration both he and the Union army commander were constrainted by the realities of warfare to obey.

Certainly Stuart’s cavalry could make no contribution to the battle itself, for cavalry had no place on a Civil War battlefield: The horsemen charging around would be wiped out quickly by the massed infantry fire of the long range rifles available, their range extending 1,000 yards, accurate fire at 700 to 800 yards. Cavalry stands on the sidelines when the King of Battle (infantry) is at work. The cavalry of both sides did collide in a separate battle on July 3rd, some three miles from the battlefield at Gettysburg, but it added no advantage to the scales of victory for either side.

John S. Mosby, Stuart’s Cavalry in the Gettysburg Campaign, Moffat, Yard & Co. 1908

Edward G. Longacre, The Cavalry at Gettysburg, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1986

Mark Nesbitt, JEB Stuart and the Gettysburg Controversy, Stackpole Books, 1994

Historical Publication Committee, Encounter at Hanover: Prelude to Gettysburg, 1963

Frederic Shriver Klein, Just South of Gettysburg, Newman Press, 1963