About Publications Library Archives

cthl.org

Preserving American Heritage & History

Preserving American Heritage & History

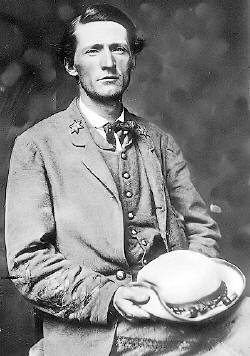

Colonel John Singleton Mosby, son of Alfred D. Mosby. of Amherst county, was born December 6, 1833, at Edgemont, Powhatan county, the residence of his maternal grandfather, Rev. McLaurin. At the age of sixteen years, he entered the University of Virginia, where his course of study was terminated by an unfortunate difficulty with a fellow student, in which the latter was wounded. Mosby was punished for this affair by imprisonment, but the attorney who had vigorously prosecuted him aided him during this confinement in the study of law, the profession which he subsequently followed at Bristol, Va.. until the secession of Virginia. During his residence at Bristol, he married Pauline, daughter of Beverely J. Clarke, of Kentucky, prominent in the United States Congress, and the diplomatic service.

Colonel John Singleton Mosby, son of Alfred D. Mosby. of Amherst county, was born December 6, 1833, at Edgemont, Powhatan county, the residence of his maternal grandfather, Rev. McLaurin. At the age of sixteen years, he entered the University of Virginia, where his course of study was terminated by an unfortunate difficulty with a fellow student, in which the latter was wounded. Mosby was punished for this affair by imprisonment, but the attorney who had vigorously prosecuted him aided him during this confinement in the study of law, the profession which he subsequently followed at Bristol, Va.. until the secession of Virginia. During his residence at Bristol, he married Pauline, daughter of Beverely J. Clarke, of Kentucky, prominent in the United States Congress, and the diplomatic service.

He was first advised of the action of the Virginia convention, at Abingdon, and immediately enlisted in the Washington Mounted Rifles, under Capt. William E, Jones. He joined Stuart’s cavalry at Bunker Hill and made his first scout at Bull Run. When Jones became colonel of the First Virginia cavalry he was appointed adjutant of the regiment, with the rank of lieutenant. He captured his first prisoners in a scout from Warrenton in the spring of 1862.

When Jones was transferred to another regiment, Mosby was invited by Stuart to remain with him as a scout, and, in this capacity, he made a reconnaissance preparatory to Stuart’s famous Chickahominy raid, and as the guide led that expedition. After the Seven Days’ campaign, being sent in the direction of Fredericksburg, he saw the opportunity for independent service in Fauquier county and asked for such orders, but instead was sent to General Jackson. En route, he was captured but was exchanged in time to give Lee the information of Burnside’s movement toward Fredericksburg, and serve with Stuart in the Second Manassas and Maryland campaigns. He made an important scouting expedition before the battle of Fredericksburg and soon afterward was granted independent command.

General Lee, in his report of Confederate successes during the winter, noticed that Lieutenant Mosby had done much to harass the enemy, attacking him boldly on many occasions and capturing many prisoners. Thus began his famous operations, which continued throughout the war, and contributed in no slight degree to the success of the army. While in a sense independent, his command was always part of the cavalry of the army, and he made reports regularly to General Stuart or Lee.

During this period he was still of youthful appearance-was not of imposing frame, scarcely of medium height. In manner he was undemonstrative, but his brilliant gray eye revealed the gallant and friendship he was warm and tenacious. His mode of warfare, the object of which was to cut off the enemy’s Supplies and disturb his communications, was the same that made Platoff the hero of Russia during the French invasion and was commended by Jomini. His men had no superiors in the saddle and were expert pistol shots. They used neither sabers nor carbines. They were never very numerous, but what they lacked in numbers was Compensated for by high intelligence, inspired by reckless daring. Among them were some who deserve to rank with the heroes of romance. His rank in March 1863, was captain, but he was soon promoted major, and toward the close of the war had the rank of colonel.

Often large forces were sent against him, but he always evaded and frequently defeated them, capturing many prisoners. In March 1863, he captured the Federal General Stoughton, in camp near Fairfax, and a number of his men. During the battle of Chancellorsville, he attacked a Federal cavalry brigade, capturing several hundred prisoners. Near Chantilly, again, he defeated a large body of Federal cavalry, leading General Lee to exclaim: “Hurrah for Mosby! I wish I had a hundred like him.” Near Dranesville, with 65 men, he defeated 200 of the enemy and captured 83 prisoners. One of his most daring adventures was a reconnaissance in the Federal lines, by order of General Lee, after the battle of Chancellorsville, in which he and one companion captured six men, and with two of them, rode undetected past a column of Federal cavalry.

On another occasion, he rode in sight of the Washington capitol, and by a countryman, sent President Lincoln a lock of his hair, a token which Lincoln’s keen sense of humor fully appreciated. In addition to the numberless encounters along the border, he was of valuable service to Stuart in all his famous raids, including the movement into Pennsylvania, preceding the battle of Gettysburg.

Another very important service was his defeat of Sheridan’s plan to join Ulysses S. Grant, in the fall of 1864, by rendering it impossible for the Federals to rebuild the Manassas Gap Railroad, necessary to furnish Sheridan supplies and transportation. After the surrender at Appomattox, it was understood that he was not to be included in the terms granted to Lee, and on April 18th he made a truce with General Hancock at Winchester, pending negotiations. General Grant secured proper treatment of the brave officer and he surrendered at Salem, April 21, 1865, having then 600 men in line. His subsequent life was influenced greatly by the strong friendship between him and the great general who had ordered his honorable parole. He supported the candidacy of Grant for the presidency as the best way to restore amity in the Union but declined the office. Finally accepting the consulship at Hong Kong, under the administration of President Hayes, he won distinction by the official life. Subsequently, he returned to the practice of law and made his residence in San Francisco.

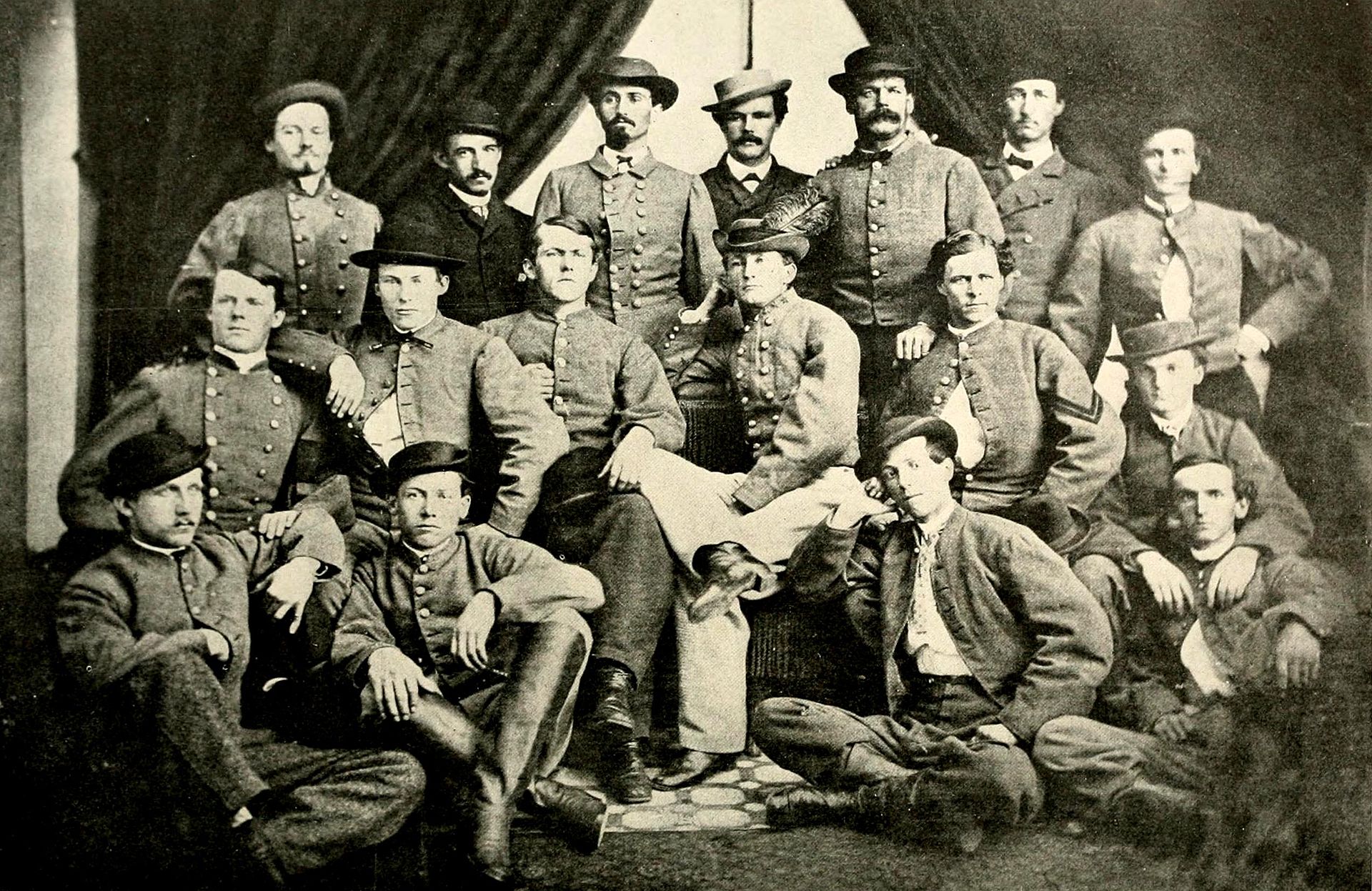

43rd Battalion, Virginia Cavalry (Mosby’s Raiders)

The total tally for the 43rd Battalion by October 1864 was 1,600 horses and mules, 230 beef cattle, 85 wagons and ambulances, and 1,200 captured, killed or wounded, including Union Brig. Gen. Edwin H. Stoughton who was captured in bed.