About Publications Library Archives

cthl.org

Preserving American Heritage & History

Preserving American Heritage & History

The North and the South were divided on an issue of human rights, but they were also divided over Christianity. Denominations were split. People on both sides pointed to the Bible in support of the looming, bloody war. And the religious ideologies of the time continue to affect Americans today.

In the decades before the Civil War, Christianity was blossoming in America. There were about 2,500 congregations in the states at the time of the American Revolution. By 1860, there were around 52,000, a nearly 2,000% increase in what is often called the “Second Great Awakening”.

First Presbyterian Church played a central part in the intersection of faith and the war. Thomas Hooke McCallie, whose children would later found McCallie School, led the church during the fighting. Jonathan Waverly Bachman, a native of Sullivan County, fought for the Confederates and served as a chaplain from October 1864 until the end of the war. After the fighting, Bachman became the pastor at First Presbyterian.

Oliver Otis Howard, a Union general from Maine, fought in the major battles of Chattanooga before leading Union forces as part of Major General William Tecumseh Sherman’s March to the Sea. After the war, Howard University in Washington, D.C., and Howard School of Academics and Technology in Chattanooga were named after him.

The increase in religion in the country meant the Civil War had to involve houses of worship, the majority of which supported the geographic ideology. Protestantism was the dominant denomination, but a sermon at a Methodist church in the South sounded widely different from one in the North.

Many Bible scholars and pastors at the time focused on interpreting the Bible literally. Southern faith leaders said the Bible endorsed chattel slavery, since it is mentioned in the story of Noah and by St. Paul, who in multiple letters said slaves should respect their masters. Given these references, Northern faith leaders had a more difficult argument to make, said Chris Carpenter, McCallie School dean of student academics.

“Jesus spoke about all kinds of different things. He did not speak about freeing slaves,” he said. “So it’s not only the verses that are about it, but it’s the omission of verses that are against it.”

Northern leaders had to make the case slavery was incompatible with the tenets of the faith, Carpenter said. The war would be the punishment for slavery. In the South, the suffering of battle was seen as a test of faith, much like the biblical story of Job. The majority of Christians on both sides believed bloodletting was necessary, Carpenter said.

When the war began, faith leaders on both sides said their army was fighting a just war and God was on their side, historians said.

This notion of divine providence directly affected the armies in the field, Guelzo said. A loss meant God was angry and the soldiers needed to double their repentance efforts to win back favor. Revivals in army camps were common. The army chaplain population swelled.

There were never enough military chaplains to meet the perceived needs of soldiers and their families, Carpenter said. There was gambling, drinking, sexual promiscuity and even cursing among the young soldiers. Generals, and the more religious soldiers, were concerned this believed heathenism would lead to God’s punishment. Families at home worried the soldiers’ loose ways could jeopardize their salvation.

Soldiers would write in letters home saying God gave them dispensation to swear. Chaplains often had to assure families their sons died painlessly and believing in God. At the time, people’s final words were cherished and seen as important indicators for salvation.

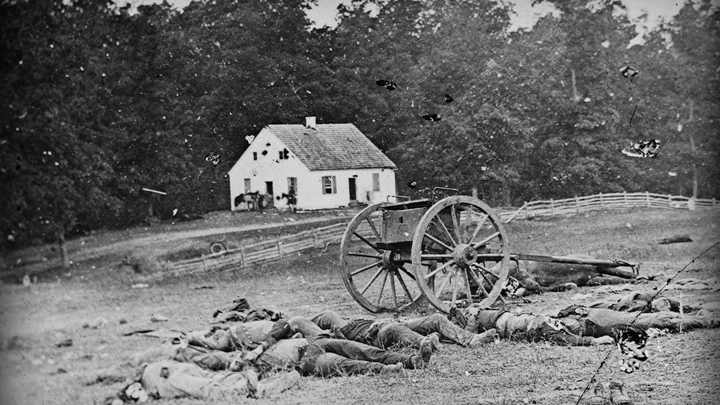

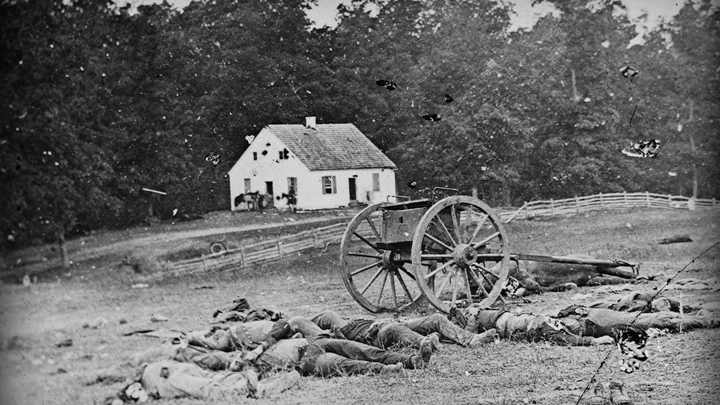

In the battlefield, churches were used as hospitals. Congregations met rarely, causing the churches to struggle financially. Faith leaders were also tasked with helping soldiers make sense of the violence they were seeing.

President Abraham Lincoln, who never had much of a religious profile, looked for a message from God in creating the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863. He saw God’s will in freeing the slaves. By that point, the South lost its momentum in the fighting, a major blow to the religious self-confidence of the Confederacy.

On the anniversary of the major Civil War battles in Chattanooga — the Battle of Lookout Mountain on Nov. 24, 1863, and Missionary Ridge on Nov. 25, 1863 — this story looks at the role faith played in the war then and today. Jim Ogden, historian at Chickamauga National Military Park, said this history has been lost.

“The whole … religious aspect of the era is something that certainly in the last 60 years or so has been largely ignored and is not readily noted today in some of the better histories,” Ogden said. “… Religion really needs to be written back into most of the histories of that mid-19th century period.”

“They go into this war really believing that God is on their side. Now, they’ve lost and how do you reconcile? And they come to the end of the war and it is a major factor in the ease with which the Confederacy surrenders because Southerners are looking at themselves and saying, ‘God is obviously against us in this war.'”

But the war’s end would not reconcile the faith leaders and believers on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line. The fissure had grown beyond repair.

“The Civil War creates a kind of crater in the landscape of American religion from which we are still emerging”.

Compared to other civil wars in history, the American war of four years was relatively short. A major reason for the surrender of the South was the role of faith in the war.

“The South simply rolls over and accepts its defeat,” he said. “And one factor in that rolling over is the sense is that ‘God is obviously against us.'”

On the eve of the war’s end, during his second presidential inaugural address, Lincoln underlined the religious tension the war would not resolve.

“It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged,” Lincoln said in the address. “The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes.”

While faith leaders played a prominent role in shaping social and political thought at the time of war, there was likely less church participation than people today believe.

“The religious landscape is so much different than our own time, but in ways, that might surprise people,” he said. “I think we have an idea of a society that is pervasively religious and pervasively Christian in the 19th century and I think that’s been rather exaggerated.”

The young men who were fighting the war were especially indifferent to religion. Pinning down the religiosity of those in the regiments is a difficult task.

“One of the questions that historians have talked about over the years but is hard to get a handle on is, how religious were the Civil War soldiers? And the answer that many Civil War soldiers would’ve given is not all that religious. Those who are religious think they are surrounded by heathen”.

It was common for soldiers to drill on the sabbath. Many gambled, drank and frequented brothels, much to the dismay of their hometown pastors and parents.

The end of the war in April 1865 marked the beginning of two religious trends, divided by the Mason-Dixon line, which still have influence today. The people of the South had to make sense of losing a war they felt God ordained. Residents in the North were welcoming their victory as the sign of divine favor.

Southern pastors did not tell people they were wrong for believing God was on the side of the Confederacy. Instead, the loss was re-framed as part of a larger divine plan, which gave birth to the Lost Cause myth, Carpenter said.

“The message that resonated was: ‘We lost, but we were right and your fathers and sons died fighting for noble cause,'” Carpenter said. ” This is the Lost Cause. This idea that we were fighting for our rights. We were fighting against oppression. And this is merely just another trial and tribulation for a righteous people, and (that message) came from the pulpits.”

Southern faith leaders said the loss was a form of punishment. Protestant theology shifted to say God does not always bless Christians with success. Sometimes, God blesses them with struggle and defeat as a sign of love.

The perceived sign of still being special gave a pass for the racial oppression and Jim Crow laws that came after, he said.

In the North, faith leaders had a sense of triumphalism and confidence that the war’s win was going to lead to Jesus’ return and the establishment of the holy kingdom on earth. Popular songs of the time, such as “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” underline this idea of the holy return at the end of the war.

But as the months after 1865 turned to years and decades, Northern leaders had to reconcile why Jesus had not returned. Faith leaders and followers lost confidence in revival-focused religion and a faith more rooted in social justice emerges. This social liberalism approach emphasizes meeting the immediate needs of people and rejects the more fundamental elements of Christianity.

Both dominant religious ideologies of the Civil War had to deal with failure. Some historians argue this led to more religious skepticism in the country.

But the idea of God’s work directly in the outcomes of daily life continues to influence life today, pointing to funerals when people say it was “someone’s time,” for example.

Prominent American pastors — including Pat Robertson, the Rev. Jerry Falwell and Jeremiah Wright — even said the terrorist attacks on Sept 11, 2001, were the result of national sin. People at the time reacted as though this was a new idea, when it is really an interpretation dating back to the Civil War.