On August 20, 1864, a chosen group of 600 Confederate officers left Fort Delaware as prisoners of war, bound for the Union Army base at Hilton Head, S.C. Their purpose–to be placed in a stockade in front of the Union batteries at the siege of Charleston.

The 600 were landed on Morris Island, at the mouth of Charleston Harbor. Here they remained in an open 1 1/2 acre pen, under the shelling of friendly artillery fire. Three died on the starvation rations issued as a retaliation for the conditions of Union prisoners at Andersonville, Ga. and Salisbury, N.C.

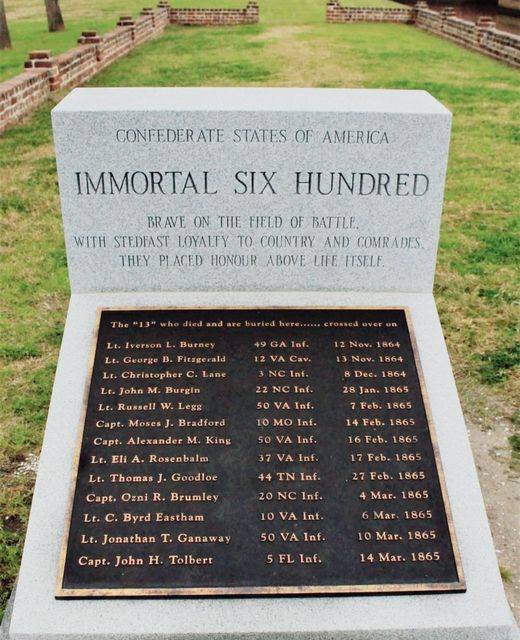

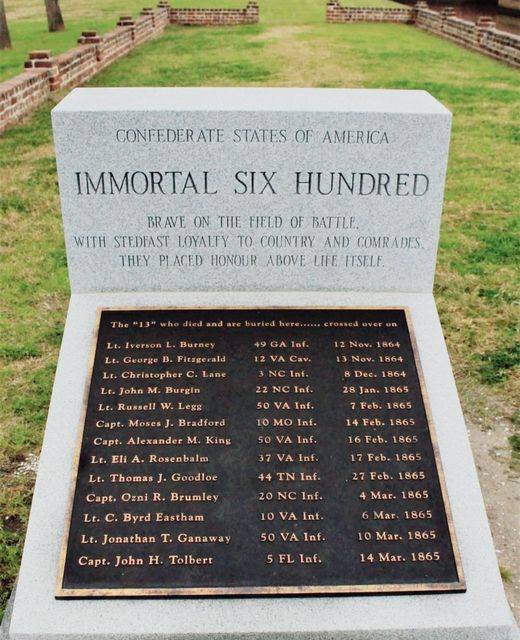

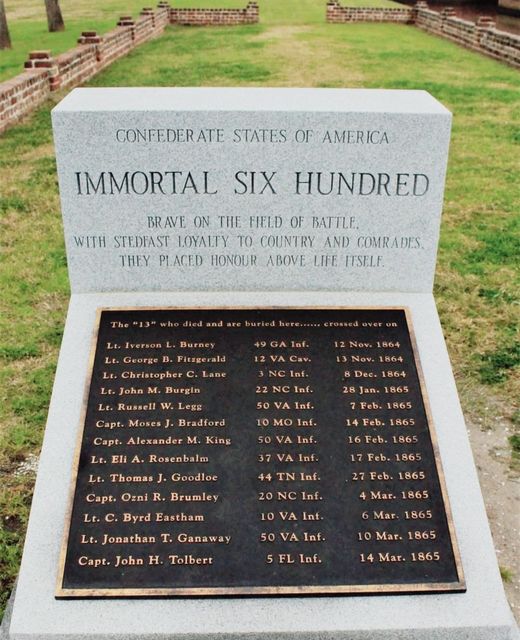

On October 21, after 45 days under fire, the weakened survivors were removed to Fort Pulaski, Ga. Here they were crowded into the cold damp casements of the fort. On November 19, 197 of the men were sent back to Hilton Head to relieve the overcrowding. A “retaliation ration” of 10 ounces of moldy cornmeal and soured onion pickles was the only food given for 42 days. Thirteen men died at Fort Pulaski and five at Hilton Head.

The remaining members of the Immortal Six-Hundred were returned to Fort Delaware on March 12, 1865, where an additional twenty-five died. They became famous throughout the South for their adherence to principle, refusing to take the Oath of Allegiance under such adverse circumstances.

To this day there has never been a monument or museum exhibit to tell the story of the Immortal Six-Hundred. The Immortal 600 Memorial Fund was established to see that their story is finally told. Tax-deductible contributions to this fund may be made to:

“Death before dishonor”: The ‘Immortal 600’ –human shields 130 years before Saddam Hussein by George W. Contant

“…your officers, now in my hands, will be placed by me under your fire, as an act of retaliation.”

With that fearful threat in the Summer of 1864 by Federal Major General John G. Foster, Commander of the Department of the South, to Confederate Major General Samuel Jones, Commander of the Department of South Carolina, events were set in motion which would change the face of the “ethics of war” forever. Foster had learned that the Rebels had removed about 600 Yankees from the overcrowded Andersonville Prison, in Georgia, and placed them in the City of Charleston because Andersonville was just too crowded. Foster knew exactly where they were located and had already made arrangements in preventing his daily shelling from hitting their position, but for him, this was not enough. After months of hearing about atrocities being carried out in Southern prisons, the North was in no mood to be understanding, and Foster quickly saw the political possibilities of “spinning” the situation in Charleston to the Union’s favor in world opinion and to retaliate by having a like number of Confederate prisoners sit “in harm’s way”.

International military custom clearly stated that the deliberate mistreatment of prisoners was illegal, but surely the world would understand that the Union must retaliate against these Rebel “fiends”. Better yet, he thought, perhaps if he placed them in front of his own artillery the Rebels might not fire at them, thereby allowing his gunners to fire on the city unimpeded. The authorities in Washington understood the political “hay” that could be made, and permission to have a Confederate officer sent to Foster was not long in coming. Soon, 600 prisoners would arrive from Fort Delaware to be placed in front of Fosters’ batteries on tiny Morris Island, in Charleston Harbor, making it impossible for the Confederates to perform counter-battery fire on those guns without possibly killing their own men. Long before Saddam Hussein placed American hostages around his missile and other military sites, the U.S. government would use “human shields” of their own. As “600” historian Mauriel Phillips Joslyn recently put it, “[t]he long history of the chivalric code, and the medieval laws of war governing captives bit the dust in that summer of 1864.”

By mid-August, the thousands of Confederate prisoners at Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island, in the Delaware River, we’re excited to hear rumors that 600 men were to leave for the South, possibly to be exchanged and sent home. On August 20, the rumors were at least partially confirmed as 600 officers were placed on the aging sidewheeler Crescent City, bound for Charleston Harbor. But, unknown to them, they were not going to be exchanged.

The trip was uneventful until just before arriving when the ship ran aground on Cape Romain Shoal, South Carolina. The Rebels, not perceiving that exchange was not in their future, immediately conspired to escape, but before long a Federal gunboat came alongside, putting an end to their plans. For the next several days they languished in the hold of the ship, not knowing what their fate would be. Another escape attempt was made on August 27, but, it, too, was foiled after the only three to escape the ship stumbled into Federal pickets onshore and were returned. They finally reached Charleston on September 1, still unaware of their true fate.

For a time the ship lay anchored under the guns of Battery Gregg, in the direct line of Confederate fire, while a rude stockade was built on Morris Island. Even though he knew it was impossible for the Confederates to move their Yankee prisoners –Sherman was wreaking havoc farther south and blocked any routes in that direction– Foster continued his war of words with his Confederate counterpart, threatening to place his prisoners on the island if the northerners were not immediately removed from the city. For Foster, things were working very well, except his continual barrage of the city was failing to cause its capitulation.

The “600” –now actually about 560, as 40 or so desperately ill men had been sent to Federal hospitals– were landed on Morris Island on September 7. Now things went awry for Foster as the Confederates were not cowed by this and continued to fire on the island. For 45 days, the Rebel officers endured shelling. A total of 18 shells exploded over the stockade and duds actually landed inside, but miraculously no one was killed. Finally, the Confederates were able to move their Federal prisoners to Columbia, South Carolina, but Foster held the “600” for another two weeks and increased the intensity of the shelling. Soon, Washington began to realize that stubborn Charleston would not surrender. Since Sherman was getting closer every day, Foster was ordered to cease firing and wait. But, even with this, the “600’s” ordeal would continue.

With the prisoners now a burden, Foster tried to get Washington to exchange them, but his idea was rejected. Instead, they were sent to Fort Pulaski, Georgia, and subjected to extremely poor living conditions and the bone-chilling Winter of 1865 –one of the coldest in memory. It wasn’t until March that they were shipped to City Point, Virginia, ostensibly for exchange. For most of them, it did not come. They were held on board, often seeing their friends from Fort Delaware passing by on their way to being exchanged, but another problem had arisen which prevented them from being released. According to Joslyn, the “600” –now down to 290– were in such poor physical condition as be an embarrassment to the Government which had been so loud in decrying the conditions of Andersonville. So, they were packed off back to Fort Delaware to be “fattened up” before release.

The remnant was not released until July of 1865. As the years after the war wore on, the survivors began calling themselves “The Immortal 600”, a phrase probably coined by “600” survivor John Ogden Murray, who wrote about his experiences in The Immortal Six Hundred. They became heroes throughout the South for their courage and for refusing to take the Oath of Allegiance before the War was over. Instead, as Joslyn put it, they chose death before dishonor.