About Publications Library Archives

cthl.org

Preserving American Heritage & History

Preserving American Heritage & History

Tensions were high in 1861, and deviations from Quakerism were made when Friends, both Northern and Southern, had to choose whether to prioritize the sanctity of union, support abolition, or remain neutral. Each of these decisions had its share of repercussions within the religious community, and the Quakers themselves found their mindsets changing as the tide of the war rolled on, whether they chose to fight, support the war effort, or abstain from involvement.

Friends had to decide which was the greater sin: violence or slavery. Quakerism preached against both, leaving its subjects in opposition to the South’s Peculiar Institution but unwilling to take up arms against the Confederacy. Some, like Daniel Wooton, enlisted for the preservation of the Union and became engaged in the morality of the fight: “We all know the Bible says thou shalt not kill: but what are we to do with those persons that rebell against the law of our country,” the young cavalryman wrote to a friend back home. “Did God set dow[n] and let the Devil take the uppermost seat in heaven when he caused the rebellion there? no Sir!” This appeal to religion serves as justification for Wooton, but it also presents a question: which tenet of Quaker faith was the most important?

This text was extracted and prepared by James Pemberton, merchant, philanthropist, and clerk to the yearly meeting of Quakers. It states that Quakers should not participate in governments active in war, or contribute to the promotion of war through business or other activity. It also condemns all forms of slavery and indentured servitude, and requires all Quakers to free anyone so held. David Brion Davis and Steven Mintz wrote in their book, “The Boisterous Sea of Liberty: A Documentary History of America from Discovery through the Civil War,” that “Slavery posed special problems for Quakers, who strove to lead sinless lives. In 1774, the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting forbade Quakers from buying or selling slaves and required masters to free slaves at the earliest opportunity. Two years later, the meeting directed Friends to disown any Quakers who resisted pleas to manumit their slaves. For Quakers, as for many later abolitionists, slavery could never be reconciled with the Golden Rule or with the other bedrock Judeo-Christian precept that God “is no respecter of Persons”—or in other words, that worldly titles, status, and privilege do not matter in the ultimate scheme of things.”

…In this time of Singular Difficulty and tryal…we are unanimous in sentiment that…friends [Quakers] should be particularly vigilant in and watchful Christian care over themselves & each other….

And as we have for some years past been frequently concerned to exhort & advise Friends to withdraw from being active in Civil Government…we find it necessary to give our sense & judgment, that if any making Profession with us, do accept or continue in public offices of any kind, either of Profit or Trust, under the present Connections, & unsettled state of public affairs, such are acting therein contrary to the profession, & principles we have ever maintained since we were a religious society…. We are United in judgment that such who make religious profession with us and do either openly or by connivance pay any fine, penalty or tax in lieu of their personal services for carrying on the war under the prevailing commotions, or who do consent to, and allow their children, apprentices, or servants to act therein, do thereby violate our Christian testimony and by so doing, manifest that they are not in religious fellowship with us….

We affectionately desire, that Friends may be careful to avoid engaging in any trade or business tending to promote war, and particularly from sharing or partaking of the spoils of war, by buying, or vending [selling] prize goods of any kind….

On the subject of obtaining liberty to the Bondmen among us…a Committee of 32 friends was appointed…. It is earnestly recommended…to persevere in a further close Labour for the Convincement of those professing with us, who yet continue in the Iniquitous Practice of depriving any of their just right to Liberty, and for the exaltation of our Testimony against it, agreeable to the sense of judgment of the said committee….

We the committee appointed to take under our Consideration the deeply affecting case of our oppressed fellow men of the African race and others as also the state of those who hold them in Bondage, have several times met and heard the concurring sentiments of diverse other friends and examined the reports form the Quarterly meetings, by which it appears that much labor & care hath been extended since the last year for the Convincement of such of our Members who had, or yet have them in possession, many of whom have of late from under hand & seal properly discharged such as were in their position from a State of slavery.

Yet sorrowful it is, that many there are in Membership with us, who, notwithstanding the Labour bestow’d still continue to hold these People as Slaves under the Consideration whereof we are deeply affected, and United in Judgement, that we are loudly called upon to a faithful Obedience to the Injunction of our blessed Lord “to do all Men as we would they should do unto us” and to bear a clear testimony to these truths that “God is no respecter of Persons” and that “Christ died for all Men without distinction,” which we earnestly and affectionately entreat may be duly consider’d int he awful and alarming Dispensation, and excite to impartial justice and judgment to black and white, rich and poor.

Under the calming influence of pure love, we do with great unanimity give it as our sense & judgment that quarterly & Monthly Meetings should still speedily unite in further close labor with all such as are slaveholders and have any right of membership with us, and where any members continue to reject the advice of their brethren, and refuse to execute proper instruments of writing for releasing from a state of slavery such as are in their power, or on whom they have any claim, whether arrived to full age or in their minority, and no hopes of the continuance of friends labor being profitable to them that Monthly meetings, after having discharg’d a Christian duty to such should testify their disunion with them….

Even as Wooton enlisted and became more supportive of the Union cause, some Quakers were caught up in the dilemma of conscription. Those who wished to remain free of the violence attempted to push for conscientious objector status, but they were often met with hefty fines to avoid the draft and public disapproval. In April 1862 a group of North Carolina friends visited the State Assembly in an attempt to plead for exemption, which was granted “upon the payment of a $100 tax or the performance of alternative service, such as working in the coastal Salt Works or as medics.” This was nullified by the Confederate Conscription Bill passed only two days after, and it was not until that October that Quakers were free from the draft by the Exemption Act. The act did, however, require friends to send a substitute or pay a $500 fine.

Quakers were thus faced with choosing isolation from their faith or their communities. Some who decided to take up arms were scrutinized and condemned by the Society of Friends, but those who abstained from combat, both Union and Confederate, were accused of being unpatriotic and sympathizing with the adversary. Quaker civilians also faced difficult choices; though she was a Southerner, Delphina Mendenhall welcomed starved and tattered Union soldiers into her home because it aligned with her religious principles of generosity and compassion. This would not have been a popular act, but it attests to the dedication and morality of the Quakers.

The war certainly complicated life for Friends, making them choose between different compelling yet contrasting ideologies of their faith. They were forced to pick the lesser of two evils, faced either with disapproval from their congregation or moral conundrum. Some would not even support the war effort, believing that it was inherently against their moral and religious code. For Quaker soldiers, however, the war served to enhance their decision to fight. Daniel Wooton, who had enlisted apprehensively and spent his first few years battling shame and regret, became hopelessly devoted to his service after the Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, appealing to faith and God to justify his decision: “I came to the conclusion by serving my country I would be serving my God and friends also, there fore I resolved to enlist and risk my chances with that of my fellow soldiers.”

There is no one trend, then, for Quaker behavior in the Civil War. Each position held risks, and Friends were forced to determine which element of their religion was of the most significance: abolition or nonviolence. The motivations behind the choices made were, however, more visible. Quaker faith would remain steadfast during war time but Quaker justifications, as with all religions, were tuned to fit a moral code.

“All warfare is based on deception,” Sun Tzu wrote in The Art of War, an ancient Chinese military treatise, often regarded as one of the most influential books ever written on war strategy. For centuries, Sun Tzu’s words have been gospel for military strategist, businessmen and lawyers alike.

Military deception is as old as war itself. The great city of Troy fell to the Greeks largely because of the Trojan horse—a deception. Smoke screens, a deceptive technique used to mask the movement of military units, were first used by the Greeks during the Peloponnesian War in the 5th century BC. During the Gothic War between the Byzantium Empire and the Kingdom of Italy, Roman General Belisarius lit a long chain of campfires to exaggerate his troop’s size, causing the much larger army of Goths to flee in panic. The Mongols often lured their enemies into traps by feigning retreat. They also used straw dummies to give an impression of a larger army.

Deception proved very fruitful during the American Revolution in 1780. When the continental forces under the command of Colonel William Washington attacked a fortified barn near Camden, South Carolina, where the Loyalists under Colonel Henry Rugeley had barricaded themselves, the Colonel asked his men to surround the barn and prepare a pine log that resembled a cannon. He pointed the “cannon” towards the building and threatened to blow it away if the Loyalists didn’t surrender. Rugeley’s men meekly surrendered without a single shot having been fired.

Quaker guns played a small but significant role during the American Civil War. From the American Civil War: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection:

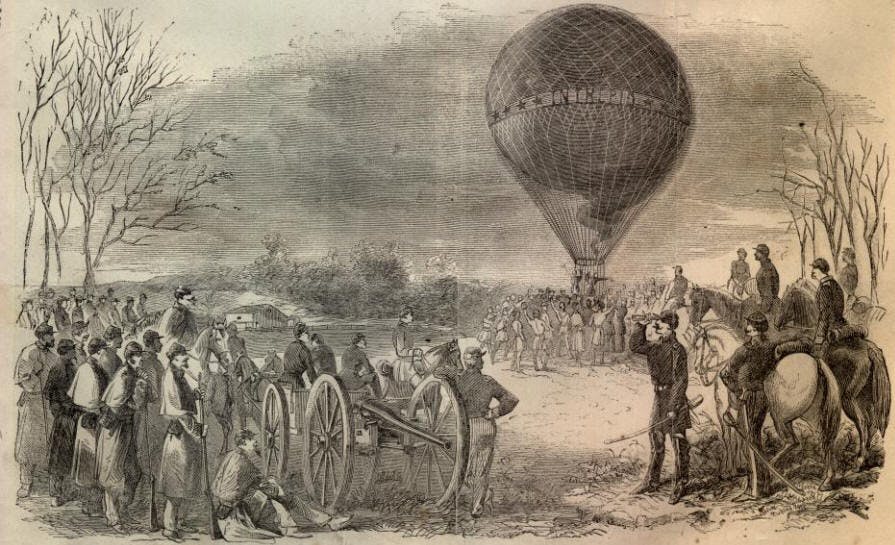

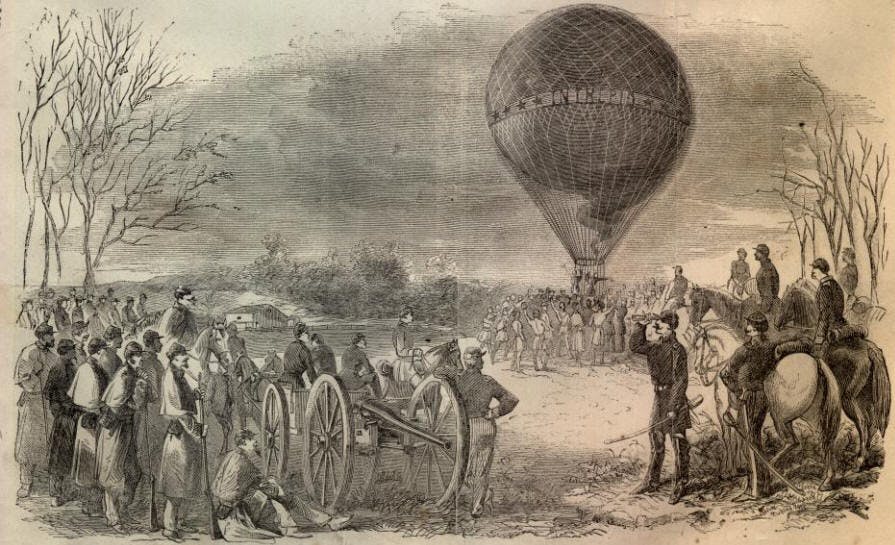

One early example of Quaker guns occurred on September 28, 1861, when Confederate forces evacuated Munson’s Hill , Virginia, leaving their earthworks to an advancing Union force. When the Union soldiers reached the Confederate lines, they discovered two logs and one stovepipe guarding a shallow ditch rather than the three Parrot guns reported by Union scouts.

During Major General George B. McClellan ‘s Peninsula Campaign (March—July 1862), Confederate defenders attempting to delay the Army of the Potomac again resorted to deception. In early 1862 McClellan, never an aggressive commander, refused President Abraham Lincoln’s repeated request that he advance south from Washington to Richmond, choosing to believe reports that he faced almost 100,000 Confederate troops at Manassas Junction, supported by more than 300 artillery pieces. In reality, his front was opposed by only 40,000 soldiers and a wide assortment of Quaker guns. McClellan’s hesitation combined with the gullibility of Union scouts led to a delay of weeks, which allowed Confederate general Joseph E. Johns ton to organize the defenses of the Confederate capital.

When Johnston ordered the evacuation of the Manassas-Centreville line, newspaper reporters quickly noticed that he had left a significant quantity of desperately needed artillery. To McClellan’s humiliation, after closer inspection it was determined that the ”artillery” were logs painted black. In the Siege of Yorktown (April 5—May 3, 1862), Confederate major general John B. Magruder also made extensive use of Quaker guns. The Union side also employed Quaker guns in the Peninsula Campaign (March-July 1862).