About Publications Library Archives

cthl.org

Preserving American Heritage & History

Preserving American Heritage & History

John Tyler is famous for being the first vice president in the history of the United States to assume the full power of the presidency upon the death of a sitting president.

John Tyler is famous for being the first vice president in the history of the United States to assume the full power of the presidency upon the death of a sitting president.

In what became known as the “Tyler Precedent”, John Tyler’s rise to the presidency happened rather fortuitously, as some may describe. It is for this reason his opponents and detractors called him “His Accidency” — meaning someone who came to the presidency by accident.

With the exclusion of the Annexation of Texas, which happened towards the end of his tenure, John Tyler typically goes down the historical annals as one of the least memorable U.S. presidents.

John Tyler’s date of birth was March 29, 1790. He was born on a plantation in Virginia. His parents were John and Mary Armistead. In total, Tyler had seven siblings – two brothers and five sisters.

Aside from being a plantation owner, Tyler’s father was heavily involved in the American Revolution; he was also a Virginia governor and a federal judge. The Tyler family also had huge admiration for Thomas Jefferson.

When John Tyler was 7, he lost his mother, Mary Armistead. Five years later, he secured admission into the prestigious College of William and Mary Preparatory School. Tyler spent close to 5 years in the school, graduating in 1807. He then studied law and got admitted to the bar in 1809.

John Tyler and Letitia Christian got married on March 29, 1813. Their marriage produced seven children.

A couple of years prior to Tyler becoming president, Letitia Christian Tyler suffered a stroke. She would, however, recover slightly but later succumb a few years after her husband made it into the white house – she died in 1842.

Tyler remarried a couple of years later. He got married to the 24-year-old Julia Gardiner on June 26, 1844. He was 30 years older than her and their marriage was done in secret because his daughter hated their union. Tyler had seven children with Julia Gardner.

Very surprising for the time, all 14 children of John Tyler survived into adulthood. In total, he had 8 sons and six daughters. Like their father, some of the children joined the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. For example, John Tyler Jr. served as the Assistant Secretary of War.

Another son of his, Lyon Gardiner Tyler (1853 – 1935), went on to become the President of the College of William and Mary from 1888 to 1919.

Due to his father’s friendship with Thomas Jefferson, John Tyler grew up being a strong advocate of Jeffersonian policies and views. He initially considered himself a Jeffersonian Republican, pushing for greater state rights and freedom.

Starting his political career in 1811, as a member of the Virginia Legislature, he would go on to serve in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1811 to 1816. He made a return to the House on two separate occasions – 1823 to 1825; and 1838 to 1840.

When the War of 1812 broke out, John Tyler enlisted in the Virginia militia. However, he did not feature heavily in any battles of the war.

Between 1816 and 1821, he served as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives. He represented the 23rd district in Virginia. Also, he was the 23rd governor of the state of Virginia between 1825 and 1827. Shortly after his governorship tenure was over, John Tyler became a U.S. Senator, serving from 1827 to 1836.

In the lead-up to the 1840 presidential election, the Whig Party paired John Tyler with party nominee William Henry Harrison. The duo developed quite a very good partnership. They came to be known as “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too”.

Thus, Tyler was crucial in their win over incumbent President Martin Van Buren. The Virginia-born politician was able to offer Harrison and the Whig Party the needed support from the South.

As vice president of William Harrison, John Tyler served for only 32 days. He spent many of those days not even in the capital Washington D.C., but at his home state Virginia.

10th President of the United States

10th President of the United StatesUpon the death of President Harrison, John Tyler was sworn in as the 10th President of the United States. His oath was administered on April 6, 1841.

Due to the absence of any legal framework in the Constitution providing for the death of a sitting president, Tyler could not take for himself a vice president. The U.S. had hit a constitutional quagmire: should the vice president take full powers of the presidency or should he just serve as an acting president. Tyler insisted on the former. He ascended to the presidency, taking full powers of the office. Three days after his swearing-in, he is reported to have given an inaugural speech. Such was Tyler’s strong desire to quickly stamp himself in all the full glory of the presidency.

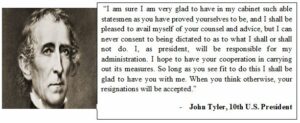

However, Tyler’s swearing-in as president was met with some amount of resistance from Harrison’s cabinet. Many of them were opposed to Tyler acquiring the full powers of the presidency. Some of them even wanted him to serve in an acting capacity. The strong-willed Tyler did not even budge when some of Harrison’s cabinet insisted that he consult with them before making any executive decision.

John Tyler was a man of his own, caring little about what his cabinet or party said. He bulldozed his way through many decisions. In so doing, many of his cabinet members had extreme difficulties working with him. With the exclusion of his Secretary of State Daniel Webster, all the cabinet that he inherited from his predecessor, William Harrison, resigned by September 1841.

As time progressed, he also fell out of favor with his Whig Party. He was quick to use his veto to halt the reestablishment of a national bank – the Third Bank of the United States. He always believed that the formulation of policies must reside at the presidency and not in the confines of Congress. John Tyler would end his tenure with no significant political affiliation or party affiliation.

During his presidency, he helped secure the Webster-Ashburton Treaty with the former colonial master, Great Britain. The treaty, which was signed in August 1842, was designed to mark the boundary between the United States and Canada. The borderline was drawn between Maine and Brunswick, Canada, stretching up to Oregon.

Tyler also secured some trade deals in China. Under the Treaty of Wanghia of 1844, American traders were allowed into Chinese ports without submitting themselves to Chinese laws.

And shortly before he left the White House, John Tyler – a Manifest Destiny enthusiast and advocate – worked very hard to secure a resolution that enabled the United States to annex Texas.

In the latter years of his presidency, it was obvious that Tyler was in no way going to win the presidential election of 1844. He had successfully alienated himself from the Whig Party; his cabinet had very little faith in him, and there was still that cloud of illegitimacy hanging over his head.

Tyler left office in March 1844 and retired to his home state Virginia, taking up a bit of farming. During his retirement from active politics, he served as the Chancellor of his former college – the College of William and Mary.

A staunch supporter of states’ rights, and the “popular sovereignty” that came with it, John Tyler backed the Compromise of 1850 that allowed for Utah and New Mexico to decide for themselves whether to be a free state or a slave state. And very certainly, Tyler was in complete agreement with the Stephen Douglas-sponsored Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 that reinforced the popular sovereignty principle.

Therefore, it was not surprising when he lent his support to the Confederacy, prior to the break out of the American Civil War. He was totally in favor of the seven Confederate states seceding from the Union.

On January 18, 1862, John Tyler died. For a couple of days prior, he had been suffering from what experts believe was dysentery because he had vomited and had severe dizziness. The final blow was the stroke he suffered on January 18.

On January 18, 1862, John Tyler died. For a couple of days prior, he had been suffering from what experts believe was dysentery because he had vomited and had severe dizziness. The final blow was the stroke he suffered on January 18.

Shortly before his death, John Tyler had gotten himself elected as a Congressman in the Confederacy. To the South’s dismay, he was unable to take up the position because he passed away.

Tyler was given a befitting burial by the Confederate States of America. His coffin was draped with the Confederate flag and buried in Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia.

In terms of the legacy John Tyler left behind, many may argue that his accomplishments as president of the United States were very minimal, barring the annexation of Texas. To show how much Tyler wanted to leave a bit of a lasting legacy, mention can be made of the bill that he signed to annex Texas, just three days before leaving office. The Treaty of Annexation of Texas, which was signed in April 1844, was initially shot down by the legislature. However, John Tyler insisted on getting a joint resolution – a joint resolution demands a simple majority in both legislative houses. In the end, John Tyler was able to get the bill passed on February 28, 1845 – just a few days before he left office.

Tyler gets quite a lot of sticks from politicians and historians today because he was the only U.S. president in history to support the Confederacy and the secession of Southern States from the Union. For this reason, he was considered a traitor for over sixty years.

John Tyler’s successor, James K. Polk – an expansionist – was inaugurated as the eleventh President of the United States on March 4, 1845.

THE PROCESSION

IN HONOR OF EX-PRESIDENT TYLER will proceed from the Hall of Congress at 12 o’clock to-morrow, under the direction of Colonel Thomas H. Ellis as Chief Marshal of the day.

It will move forward to St. Paul’s Church, where the funeral sermon will be preached by the Rt. Rev. Bishop Johns, of the Episcopal Church.

After the services in the church shall be concluded, the procession will again move forward to Hollywood Cemetery, where the remains of the deceased will be interred.

The following will be the order of the procession, viz: