About Publications Library Archives

cthl.org

Preserving American Heritage & History

Preserving American Heritage & History

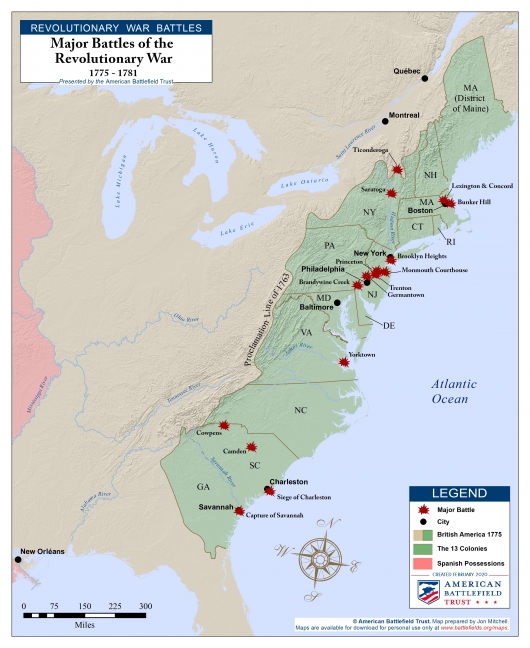

The Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Siege of Fort Ticonderoga

The Battle of Chelsea Creek

The Battle of Bunker (Breeds) Hill

The Battle of Quebec

The Battle of Long Island (Brooklyn Heights)

The Battle of White Plains

The Battle of Fort Washington

The Battle of Trenton

The Battle of Princeton

The Battle of Oriskany

The Battle of Bennington

The Battle of Brandywine

The Battle of Saratoga (Freeman’s Farm)

The Battle of Germantown

The Battle of Saratoga (Bemis Heights)

The Battle of Monmouth

The Capture of Savannah

The Siege of Charleston

The Battle of Camden

The Battle of King’s Mountain

The Battle of Cowpens

The Battle of Guilford Courthouse

The Battle of Eutaw Springs

The Battle of Yorktown

For the better part of the 17th and 18th centuries, the relationship between Great Britain and her North American colonies was firm, robust, and peaceable. The colonies enjoyed a period of “salutary neglect”; meaning that the colonial governments were more or less able to self-govern without intervention from Parliament. This laissez-faire approach allowed the colonies to flourish financially, which in turn proved profitable for the mother country as well. However, this period of tranquility and prosperity would not last.

Great Britain had amassed an enormous debt following the French and Indian War; so, as a means to help alleviate at least some of the financial burden, they expected the American colonies to shoulder their share. Beginning in 1763, Great Britain instituted a series of parliamentary acts for taxing the American colonies. Though seemingly a reasonable course of action – considering the British had come to the defense of the colonies in the French and Indian War – many colonials were livid at the levying of taxes. From 1763 to 1776, Parliament, King George III, royal governors, and colonists clashed over regulations of trade, representation, and taxation. Despite the growing unrest, many Americans perceived war and independence as a last resort.

By 1775, however, tensions reached a boiling point. Both sides prepared for war as negotiations continued to falter. Fighting began outside of Boston in the spring of 1775 during a British raid to seize munitions at Lexington and Concord. British regulars arrived on the Lexington Green early on the morning of April 19 and discovered the town’s militia awaiting their arrival. The “minutemen” intended only a show of force, and were dispersing, when a shot rang out. The American War of Independence had officially begun.

The militia harassed the British all the way from Concord to Boston, and then surrounded the city. In an attempt to drive the colonials away from the city, British forces attacked the Americans at Breed’s Hill on June 17th, resulting in heavy casualties for the redcoats in the war’s first major battle. George Washington arrived that July to assume command of the American forces, organized as the Continental Army. Washington then forced 11,000 British soldiers to evacuate Boston the following March, when Henry Knox successfully led 12 artillery pieces from Fort Ticonderoga to Dorchester Heights overlooking the city below.

By the early spring of 1776, the war had expanded to other regions. At Moore’s Creek in North Carolina and Sullivan’s Island at Charleston, American forces stopped British invasions. After initial successes, particularly the capture of Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York, an American invasion of Canada stalled and ended in failure at the end of the year. As 1775 rolled into 1776, the British rapidly built up forces in New York and Canada to strike back.

After a series of five consecutive defeats for Washington’s army at Long Island, Harlem Heights, White Plains, Fort Lee, and Fort Washington, the British captured New York City in the summer of 1776. Following the capture of the city, the British drove Washington’s army across New Jersey, winning several additional battles along their advance. That winter, however, Washington revived the American cause by winning spirited victories at Trenton and Princeton, New Jersey.

In 1777, the British launched two major offensives. In September, General William Howe captured Philadelphia, winning battles at Brandywine and Germantown. Despite the losses, the inexperienced soldiers of the Continental Army performed well and gained a measure of confidence, believing that they could very well stand up to the British. Then, in October, British General John Burgoyne invaded upstate New York via Canada, winning several initial victories. Later, however, his army became bogged down thanks in part to efforts of American militia units at Oriskany, Fort Stanwix, and Bennington. Then, after a stunning defeat in an open battle, Burgoyne surrendered his entire field army at Saratoga, New York.

The American victory at Saratoga was a turning point of the war, for it convinced the French monarchy that the Americans could actually defeat the British in battle. As a result, a formal military alliance was signed between the French and American governments in 1778, which entailed increased financial and military support. The alliance had even more positive implications for the Continental Army, because it forced the Parliament to funnel manpower and resources to fight the French across the globe, rather than sending them to North America.

That same winter, a few months prior to the formal signing of the alliance, Washington’s army retired to Valley Forge, not far from the British garrison in Philadelphia. While arriving rather disheveled, disheartened, and largely undisciplined, the army underwent a rigorous training program under the direction of Baron von Steuben. He instilled in the soldiers a sense of pride, resilience, and discipline, which transformed the army into a force that was capable of standing toe-to-toe with the British.

In 1778, the British consolidated their forces in New York and Canada and prepared to launch an invasion of the South. In the meantime, in the west, American forces under George Rogers Clark captured several British posts, culminating with a victory at Vincennes, Indiana, and the surrender of a much larger British force.

To the North, the British abandoned Philadelphia for New York with Washington hot on their heels. His army caught up to the redcoats at Monmouth, New Jersey, where an intense battle ensued. After arriving late to the battle and rallying his wavering troops, Washington made several defenses and counterattacks against the surging British force. Though inconclusive with no clear victor, the battle demonstrated the growing effectiveness of the Continental Army. Upon finally reaching New York, British forces never again ventured far from their secure base there.

In 1779, with fighting on a global scale and a stalemate developing in the North, the British began to focus their efforts on conquering the South, in hopes of quelling the rebellion once and for all. That autumn, British forces captured Savannah and Charleston and smashed General Gates’ army in Camden, South Carolina, forcing his army’s surrender. However, the Continental Army won battles at King’s Mountain and Cowpens, stemming the tide of British advance. Undeterred, the British army under General Charles Lord Cornwallis then moved across North Carolina before fighting its way into Virginia.

While General Cornwallis fought his way into Virginia, a brutal civil war erupted among the civilian population of the Carolinas. General Nathanael Greene recaptured most of South Carolina, fighting battles at Ninety Six, Hobkirk’s Hill, and Eutaw Springs. While Greene lost most of the battles in which he fought, he skillfully used his mixed force of militia and Continental regulars to maneuver the British out of the Carolinas’ interior, forcing them toward the coastal cities and towns.

By the summer of 1781, Virginia was ablaze with battles along the colony’s coast and across its center. As General Marquis de Lafayette doggedly forced Cornwallis toward the coastal defenses around Yorktown, Virginia, he persuaded Washington to move the Continental Army from Connecticut to Virginia. Washington, along with a French fleet and army commanded by General Rochambeau, arrived in Virginia on September 19th, 1781, effectively sealing shut any escape route for Cornwallis. Following a siege and a series of attacks on the British position, Cornwallis surrendered his army to Washington.

“Surrender of Lord Cornwallis”Oil painting by John Trumbull, 1820

Following Yorktown, both sides consolidated their forces and waited while peace negotiations took place in Paris. There were many small actions near New York City, in western Pennsylvania, and along the Carolina coast, but large-scale fighting had ended. At the time that the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, ending the war in favor of the American colonists, the British still controlled Savannah, Charleston, New York, and Canada.

The War of Independence is forever ingrained within our American identity and provides all Americans a sense of who we are, or, at the very least, who we should be. Our forefathers fought for liberty, freedom, and republican ideals the likes of which had never before been seen in any style of organized government preceding them. In many ways then, the American Revolution was an experiment: an experiment which overthrew the rule of a foreign power; an experiment which defeated the world’s most powerful military; and an experiment which laid the groundwork for a nation attempting to create itself. The low din of battle, fought all those years ago, continues to echo the hearts and minds of Americans to this very day.

In collaboration with Battlefield Trust for the Overview