About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

The Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia

The Battle of Fredericksburg began on the morning of Thursday, December 11, 1862 when invading Union soldiers attempted to cross the Rappahannock River directly across from the town of Fredericksburg on a hastily constructed pontoon bridges being built under a shroud of thick fog.

Fording the river was not feasible for the Union Army of the Potomac; the ice was half an inch to an inch thick in places, and more men would have been lost to exposure than to enemy fire.

The Confederate defenders, under the cover of the fog, fired at the military engineers constructing the bridges from the town, hiding in the cellars of the houses when the Union artillery fired on them in an attempt to prevent them from stopping the bridge construction. Eventually, after seven hours of delay, the Union forces ferried troops in boats across the river to drive the Confederates from the town. The attacking Yankees suffered substantial losses in the process of

creating a bridgehead for the pontoon bridges to be completed. The defending Confederates withdrew to their main lines on the heights that ran parallel to the west of the town

With the construction of the pontoon bridges done later that evening and with the town firmly under Union control, US Major General Ambrose Burnside ordered his 122,000 man Army of the Potomac across the bridges on Friday, December 12th.

Meanwhile, on the hills and high ground beyond Fredericksburg in hastily dug trenches and earthworks, the 78,500 men of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia commanded by CS General Robert E. Lee waited.

The main action of the battle began on the cold and foggy morning of Saturday, December 13th and lasted until sunset early that evening.

The fog began to clear and the Confederates realized where the attack was coming from. A young Southern officer, Major John Pelham of CS Major General J.E.B. Stuart‘s Horse Artillery decided to head it off. Using just two cannons — one Blakley rifled cannon and one 20-pounder Napoleon smooth-bore — the young officer and several men charged to the front of his own lines and began to shell the flanks of the Union attackers. The Blakley was destroyed after firing just one shot, but the reliable Napoleon poured a solid shot into the Yankee lines. His single gun was the target of four Union cannon batteries (about 20 or so artillery pieces), but he and his men refused to withdraw until they were almost out of ammunition. Pelham’s actions help up the Union advance for half an hour, buying time for the Confederates to get their position ready.

Seeing the young man in action, General Lee said to his aides, “It is glorious to see such courage in one so young.” Pelham would be killed three months later on Tuesday, March 17, 1863, at the ripe old age of 25. In memory of his courageous actions at Fredericksburg he would be remembered by history as “The Gallant Pelham.”

The Union plan was to turn the Confederate right (southern) flank, attacking under the cover of fog, but for some reason, General Burnside changed his mind about committing the whole of his Grand Division; part of which was kept back in reserve. In an ironic twist of history, had the whole division been in position there when Union soldiers under US Brigadier General George G. Meade made the only successful breakthrough of the Confederate position — and taking an estimated 3,000 prisoners in the process — they might have successfully held off the counterattack by CS Brigadier General Jubal Early‘s reserves and even turned the battle into a decisive Union victory.

In spite of Meade’s brief breakthrough, the fortified Confederate lines on their southern flank commanded by CS Major General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson held. It is said that Jackson later remarked, “I did not think a little red earth would frighten them. I am sorry that they are gone. I am sorry I fortified.”

The Sunken Road And Marye’s Heights

On the northern flank, the battle was taking a very different course.

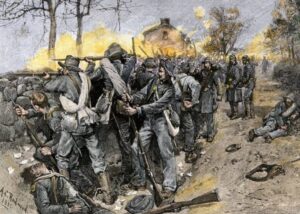

The sunken road at the foot of Marye’s Heights was the perfect natural defensive position. The defending Confederates dug a small trench into the road near the stone wall that bordered the sunken road from the then steep, wide-open plains between the town and the Confederate position. The sunken road runs along the foot of the Marye’s Heights on top of which CS Major General James Longstreet‘s artillery was positioned. The sunken road itself was defended by 2,500 Georgia soldiers under the command of CS Brigadier General Thomas R.R. Cobb — who would later be mortally wounded fighting with his men.

To make the position more challenging for the Yankee invaders, there was a four-foot deep drainage canal about several hundred yards in front of — and running parallel to — the stone wall itself. On the day of the battle, the canal was full of icy water that some Union soldiers attempted to ford, and later would die from exposure to the cold. The attacking Union regiments had to cross this canal on wooden planks and reform their units hastily under constant deadly artillery fire from Marye’s Heights.

By noon of that day, General Burnside concentrated his attacks on Marye’s Heights, ordering his brigades to storm the heights and take the stone wall.

The first Union assault came in the freezing late morning and was halted by the defending Confederates with a steady barrage of rifle fire. By firing volley after volley in shifts of four lines — one ling moving up while the first went to the rear to reload and the others repeating this action — Cobb’s Georgia troops poured constant fire onto the advancing Yankees.

To make matters even worse for the Union attackers, Confederate artillery on Marye’s Heights had the ground before the stone wall covered and well sighted. In the almost prophetic words of CS Colonel E. Porter Alexander, General Longstreet’s chief of artillery, “General, we cover that ground now so well that we will comb it as with a fine-tooth comb. A chicken could not live in that field when we open on it.”

It is hard to visualize the slaughter that took place that bitterly cold December day.

Just try to imagine if you were one of those blue-coated men for a moment. You cross over hastily laid planks over a freezing drainage trench, feet and legs cold from the icy water. You hastily form up into lines, all the while solid cannot shot slams down around you, throwing men around right and left in bloody messes. Then, on command, you march forward, up a steady inclining ground towards the stone wall with musket balls flying all around you. Men falling down in the line. Stepping around not just the dead, but the dying — bloody men who might reach out for help in their pain, or try to stand up at the most inappropriate moment. Then the closer you get to the stone wall, the cannons would fire out canister shot — large balls of iron effectively turning a smooth-bore cannon into a giant shotgun. Gaps would appear in the line. Then suddenly either you would be shot down and join the growing under of wounded and screaming men and boys, or you would be tripped and land among them, realizing that the bodies of those men were your only chance to block the bullets fired from the rifles of the entrenched screaming and cheering Confederates shouting their terrible Rebel Yell.

On the other side of the coin, imagine if you were one of the Confederates defending that stone wall. While the wall itself — entrenched in places with wooden abatis — and trench provided a little protection, musket balls would still fly over the top of the wall. Imagine you were there behind that wall, cold and afraid, hearing the bullets fly over past your head, even slamming into the stone in front of you. Also imagine men and boys — some of them friends and neighbors — falling around you as musket fire takes off the top of their heads, the trench pulling up with blood beneath your feet. Hearing the shouts and hurrahs of the approaching Yankees. Imagine placing your rifle on the top of the wall, pulling the hammer back, awaiting the command to fire, the whole time thinking the next bullet whizzing past could take out your eye, or much worse.

On the one hand, there must have been the strange and fierce exhalation of battle as they loaded and fired in shifts in almost mechanical sequence. They must have felt that terrible sense of power at pulling the trigger — or simply aiming and firing as quickly as they could before a stray musket ball hit them. A soldier resting his musket on top of the wall could aim and fire with deadly accuracy. The tragic sight of all those falling and twitching bodies piling up before them must have been gruesome to behold, worse knowing that many of them were dead by their own hands.

Fourteen separate and utterly foolhardy frontal assaults were made by seven Union divisions throughout the day. No Yankee soldier made it to within twenty paces (30 feet or so) of the stone wall before being shot down. The exemplary courage of those blue-coated men cannot be denied, despite the madness of their orders and the senseless waste of life that resulted in this futile series of attacks.

At least one Union soldier, Color Sergeant Thomas Plunkett of the 21st Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry lost both of his forearms and was wounded in the chest by cannon fire from Alexander’s artillery. He picked himself and his regimental banner up, carrying the flag in the bleeding stumps of his ruined arms, holding it close to his chest, his blood staining the ripped and bullet-tattered US colors. He continued on, either in shock or in determination, until another member of the color guard took the flag from him and he was ordered to retire to the rear. For his actions during the battle, Sergeant Plunkett received the Medal of Honor.

The insanity of the attack on Marye’s Heights only ended with the early December sunset, and even then sharpshooters on both sides continued to pick off enemy targets throughout the night with sporadic firing.

Kirkland’s Unusual Request

The Union soldiers held their positions back in the town, but couldn’t rescue the thousands of their wounded lying with the dead in agony on the slope below Marye’s Heights. Union men unhurt on the hill stayed down, using the dead bodies of their comrades as shields for protection and warmth. Some of them even stripped their dead comrades of their overcoats and clothes to protect themselves from the bitter cold. The Confederate soldiers rested behind the stone wall but remained alert. Even exposing their heads above the wall invited a volley of bullets from the Union snipers among the dead.

The Confederate defenders sat behind the stone wall, covered in their blankets desperate to stay warm and alert to movements from the enemy. Just a few dozen yards in front of them lay nearly ten thousand dead or wounded Yankees. The injured Union soldiers were helpless and cold, many of them in terrible pain and unable to move back to their lines. Their fellow soldiers could not come forward without risk of being shot by anxious and fearful Johnny Rebs behind the stone wall.

The men and boys on both sides could only sit tight and wait for the sunrise and renewed fighting. It was a long and very terrible night.

During the night, the agonizing cries for water, and warmth filled the air. Some of these men froze to death in the night, other wounded men were literally frozen to the frosty ground in their own blood — which in many cases sealed off their wounds. Many of them could not move or were too afraid of drawing enemy fire to try. All they could do was lay there in their agony. Thousands of them. The sound those wounded soldiers made must have been an eerie and terrible out coming out of the cold, darkened fields behind the stone wall.

It was these terrible sounds of pain and fear that 19-year-old Sergeant Richard Kirkland was listening to as his regiment held the position they were assigned to, replacing the men who had been fighting in that spot most of the previous day. Even though the dying men were the enemy, an invader, it wasn’t easy for the tender-hearted young man to listen to those men and boys crying, praying, and suffering horribly. He couldn’t rest when those calls for help were so close and sounded very desperate.

No matter if a person was born in South Carolina, in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Illinois, Texas, or Massachusetts; cries of pain and misery have no accent, no uniforms.

By sunrise the next morning, young Kirkland could not listen any longer. He knew he had to do something, anything to help ease the suffering he heard.

Kirkland sought out the captain of his company and made his strange, daring, and unbelievable request. To the shock of the captain in charge of Kirkland’s company, the sergeant came to him seeking permission to leap over the wall and into danger, for the simple purpose of offering water to wounded enemy soldiers. The captain realized that sergeant Kirkland was determined to carry out his plan, but could not grant the request on his own authority.

The company commander sent Kirkland to see the regimental commander, Colonel John D. Kennedy. Kennedy had known Kirkland as his neighbor for many years and knew what sort of young man he was. He too was stunned by Kirkland’s proposal. He too could not grant approval, but neither could he deny the brave young man either. So Kennedy reluctantly authorized Kirkland to report directly to General Kershaw himself to make the request — possibly with the hope that Kirkland would withdraw his proposal right then and there.

Undaunted, Sergeant Kirkland went to Kershaw’s headquarters at the nearby Stevens House to ask permission of the general.

From a room on the top floor of the house, General Kershaw surveyed the battlefield. He too must have seen the dead and wounded enemy soldiers — and certainly risked enemy sniper fire as well. Perhaps it was this scene, one which likewise tore at Kershaw’s heart, that prepared him for his young visitor.

Aides came in and out of the headquarters. Orders and reports were being delivered, every officer wondering what Burnside would do next. How would the Confederates respond? His mind was fixed on the battle which had taken place the day before, and was preparing for another day of battle when the young sergeant approached him with his unusual request.

General Kershaw was no doubt stunned by what Sergeant Kirkland proposed to do. Like Kennedy, he too knew the young man as a friend and neighbor, knew that this boy was young and a weathered veteran of half a dozen battles, determined. He had risked his life many times over bravely fighting to defend his home from invasion. Now he sought to risk his life on what might be a foolhardy and dangerous endeavor.

At first Kershaw tried to dissuade Kirkland from the idea, telling him that if he went over the wall he would not make several yards before being killed by enemy snipers. He could have simply refused the request and ordered Kirkland back to his post. Instead he listened as the stricken young man pleaded with him to let him try and give water to some of the wounded. He also could not deny the sight of the wounded Yankees beyond the wall bothered him as well.

As his commanding officer, General Lee would so famously state looking over the same gristly sight: “It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it.”

For whatever reason, General Kershaw granted the young Kirkland his unusual request, although he told the sergeant that he could not show a white handkerchief, as it might cause the Union officers to assume that the Confederates wanted to talk, or even surrender. Kirkland knew it was a risk he had to talk about and agreed.

Kirkland Mission Of Mercy

Several men in Kirkland’s unit offered their canteens, though none of them were brave enough to volunteer to go with him over the wall. After filling the canteens at the Stevens House well and leaving his rifle, he crawled over the wall and out into the dense smoke and fog which still lingered thick on the battlefield.

Both his comrades and his commanding officer, General Kershaw, watched anxiously as Kirkland made his way out to the fallen Union soldiers.

Almost at once, the sharp sounds of gunfire filled the air around Kirkland from the Union sharpshooters. They assumed Kirkland had gone onto the field to rob the dead and wounded Union soldiers. Kirkland ignored the fire, dropping low and crawled to the nearest wounded Yankees after what must have felt like a very long time.

He sat up, resting the wounded enemy soldier’s head with great care, and began to pour water down the man’s dry and burning throat. Kirkland straightened out the soldier’s broken limb and placed a knapsack underneath the man’s head. He then covered the man with an overcoat and left a full canteen, taking the Union soldier’s empty canteen and moving to the next wounded man.

Slowly the firing stopped as the Union sharpshooters realized what Kirkland was doing and watched on in amazement. His errand of mercy brought a wave of new cries for water from the helpless men scattered on the frozen ground. Many of them were too weak and hurt to speak, but could only raise one trembling hand into the air. Their silent calls were answered by Sergeant Kirkland.

No doubt Kirkland was still scared as he carried out his mission. By no means had the shooting stopped completely along the line, and there was still great risk of being hit by an enemy sniper — or even killed by one of the frightened and pain-crazed Yankees that lay before him. Indeed there were so many wounded he could not possibly have helped all but the ones closest to the stone wall, or risk being killed or captured by the Yankees farther away.

When his first supply of canteens ran out, Kirkland walked quickly back to the well and filled the canteens a second time. When he left the battlefield and returned behind the wall, the shooting on both side rang out again, the battle temporarily continuing in that part of the battlefield. But when Kirkland once again appeared on the field, the rifles mostly became silent around him.

Several of the dying Union soldiers gave Kirkland letters to send to their families, and one gave the young sergeant his watch — which remains an heirloom of the family today.

The Angel Of Marye’s Heights

The Battle of Fredericksburg itself would end officially later that evening when both sides called for a truce to collect the dead and wounded. Burnside and his invading Yankees later retreated back across the Rappahannock River the following day. The official casualty report of the decisive Confederate victory lists a grand total of 18,030 Americans killed, wounded, and missing (12,653 Union and 5,377 Confederate) among them four generals.

According to accounts, which vary, sergeant Kirkland’s mission of mercy lasted anywhere from a few minutes to at least an hour, or so. The soldiers on both sides near him watched him intently, amazed at his courage. His own comrades cheered him. Some of the Union soldiers at the bottom of the hill even cheered him. Once he was satisfied that all the wounded men he could get to were warm and had water, he returned over the wall for the final time exhausted.

Some exaggerated accounts — mostly written after the war — suggested that Kirkland strolled out among the wounded unafraid and that the firing simply stopped while he was there as if protected by guardian angels. Highly unlikely considering the situation. Bullets were still being fired by snipers from both sides the whole time. The truth is usually less glamorous. More likely the early morning fog and the mercy of Union sharpshooters that protected Kirkland — that and staying low to the ground and likely crawling from wounded man to wounded man.

Some accounts suggest that there might have been more than one “angel” that day and that other Confederates might have gone over the wall to help. Colonel James Hagood of the 1st South Carolina Infantry noted a Confederate soldier did in fact bring water to at least one wounded Union man, who raised his canteen to signal to his comrades that he was all right, causing all Union sniping to cease briefly. Captain Augustus Dickert of the 3rd South Carolina Infantry, cited a similar incident but credited a Georgia soldier with the brave and kind act. He also noted that the soldier made his way back and over the wall “…amid a hail of bullets knocking up the dirt all around him.”

At least one modern historian (and I use that term quite loosely) suggested that the entire Kirkland story might even be a fictitious legend, based on the lack of official accounts written at the time. Also not necessarily accurate since many individual acts of courage often didn’t make official reports anyhow unless they somehow affected the course of a battle — such as The Gallant Pelhem’s stand. Kirkland’s actions took place after the major fighting had ended and did nothing to affect the course of the battle itself.

General Kershaw himself must have breathed a sigh of relief when the young sergeant returned the final time. He would remember for the rest of his life what he had witnessed. Years later, he would recall the story 18 years later when he wrote an account of Fredericksburg titled: “Richard Kirkland, the Humane Hero of Fredericksburg” for the Charleston (SC) News and Courier in January of 1880. The story would be reprinted 12 days later in The New York Times.

Confederate veteran T.M Rembert, Kirkland’s best friend in Company E who bunked with him during the War and recorded the account of his friend’s mission of mercy in his personal diary, wrote a short narrative that was published in the Confederate Veteran magazine in 1903 detailing the story told here today.

Other people who witnessed this great act of compassion included Colonel W.D. Trantham, an officer in Kershaw’s Brigade, would recall the story during a Memorial Day speech in 1899.

Sadly, Thantham would also be with Richard Kirkland when he fell mortally wounded and died at the Battle of Chickamauga, Georgia on Saturday, September 19, 1863, at the age of 20 — one of 1,657 Southern men and boys killed during the battle.

Richard Kirkland is buried at the Old Quaker Cemetery in Camden, South Carolina. Canteens are often found placed at the gravesite out of respect for his human act of compassion by admirers.

Another statue depicting Kirkland giving water to a wounded Union soldier can be found at the entrance of the National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, erected by the descendants of Union Veterans in the spirit of gratitude for the memory of this young South Carolinian — this young American.

During his life, Richard Kirkland was never honored for his act of great compassion. Nor were his actions necessarily unique as there are many stories told and untold about simple acts of great humanity during the War by men on both sides. While there is little doubt that this story is as much legend in some places as it is in fact in others, Sergeant Richard Kirkland’s selfless mission of mercy is a very human story about empathy, brotherly compassion, and great personal courage in a time of senseless and useless slaughter.

A sunken road and a wall of stoneAnd Cobb’s grim line of gray

Lay still at the base of Marye’s hillOn the morn of a winter’s day.And crowning the frowning crest aboveSleep Alexander’s guns,While gleaming fair in the sunlight airThe Rappahannock runs.On the plains below the blue lines glowAnd the bugle rings out clear,As with bated breath they march to deathAnd a soldier’s honored bier. For the slumbering guns awake to lifeAnd the screaming shell and ballFrom the front and flanks crash through the ranksAnd them them where they fall. And the gray stone wall is ringed with fireAnd the pitiless leaden hailDrives back the foe to the plain below,Shattered and crippled and frail.Again and again a new lines formsAnd the gallant charge is made,And again and again they fall like grainIn the sweep of a reaper’s blade.And then from out of the battle smokeThere falls on the lead-swept airFrom the whitening lips that are ready to dieThe piteous moan and the plaintive cryFor “water everywhere.And into the presence of Kershaw braveThere comes a fair-faced ladWith quivering lips as his cap he tips,“I can’t stand this,” he said.Stand what? the general sternly saidAs he looked on the field of slaughter,“To see those poor boys dying out thereWith no one to help them, no one to care,And crying for water! water!If you’ll let me go, I’ll give them some.Why, boy, you’re simply mad;They’ll kill you as soon as you scale the wallIn this terrible storm of shell and ball,The general kindly said.Please let me go, the lad replied.

May the Lord protect you, then!And over the wall in the hissing airHe carried comfort to grim despairAnd balm to the stricken men. And, as he straightened their mangled limbsOn their earthen bed of pain, The whitening lips all eagerly quaffedFrom the canteen’s mouth the cooling draughtAnd blessed him again and again.Like Daniel of old in the lion’s den,He walked thought the murderous air

With never a breath of the leaden airTo touch or to tear his gray-clad form,For the hand of God was there.And I am sure in the Book of Gold,Where the blessed angel writesThe names that are blessed of God and menHe wrote that day with his shining penThen smiled and lovingly wrote again,The Angel of Marye’s Heights. ~ Walter A. Clark, 1908