About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Date:1936

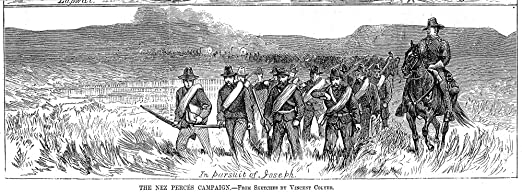

Annotation: Account of the pursuit and capture of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce in 1877.

The last great war between the U.S. government and an Indian nation ended at 4 p.m., October 5, 1877, in the Bear Paw Mountains of northern Montana. Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce nation surrendered 87 men, 184 women, and 147 children to units of the U.S. cavalry. For 11 weeks, he led his people on a 1,600 mile retreat toward Canada. He engaged 10 separate U.S. commands in 13 battles and skirmishes, and in nearly every instance he either defeated the American forces or fought them to a standstill. But in the end, the Nez Perce proved no match for Gatling guns, howitzers, and cannons.

At that moment, Joseph delivered one of the most eloquent speeches in American history. He spoke no English, but his translated remarks having handed his rifle to Col. Nelson Miles, Joseph concluded:

The little children are freezing to death…. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many I can find…. Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.

One of his terms of surrender was that his people be returned to their homeland.

For thirty-one years, Joseph fought for his peoples’ return to eastern Oregon’s Wallowa Valley, where his people had produced the famous appaloosa horse, bred for speed and endurance. He met with three American presidents to argue his case: Rutherford Hayes, William McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt. He died at the age of 64 in 1904.

In 1877, the U.S. government sent General Oliver Howard to force the Nez Perce to move to an Idaho reservation. Chief Joseph and his band left for the reservation, but before they could reach it, several Nez Perce youths, disillusioned by broken treaty promises and white encroachment on their land, attacked and killed 18 white settlers.

Chief Joseph then began a three month, 1,600 mile flight to Canada with four separate U.S. military units in pursuit. repeatedly turned the tables on numerically superior forces. They eluded and out-fought 2,000 army soldiers in 13 battles before finally surrendering in a Montana snowstorm, just 40 miles from the Canadian border. Only 418 men, women, and children out of 800 who had set out were left. During the final battle, General Miles attempted to seize Chief Joseph under a flag of truce, but the chief had to be exchanged when the Nez took a white lieutenant prisoner.

Under the terms of the surrender, the Nez Perce were promised that they could live on a reservation in Lapwai, Idaho. But instead the Nez Perce were sent to Oklahoma. Half the tribe died from disease on the trip. A decade later the Nez Perce were relocated on a reservation in eastern Washington.

The surrender of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce ended a decade of warfare between Indians and the U.S. government in the Far West. It meant that virtually all western Indians had been forced to live on government reservations.

Document: The Pursuit and Capture of Chief Joseph

By Charles Erskine Scott Wood

The battle in White Bird Canyon was the first armed conflict of the Nez Perce War. I helped bury the dead in that canyon. The next clash was the two-day battle on the north fork of the Clearwater, July 11 and 12, 1877. Then Chief Joseph’s retreat through the Lolo Pass began, only to end at Bear Paw Mountain, Montana, within about thirty miles of the British line and safety. (Joseph could easily have made his escape by pushing his march a little further, but, as General Howard anticipated, he kept his eye on our rate of progress and when we slowed down, he did the same.)

If the battle of the Clearwater is considered as the start and the surrender at Bear Paw Mountain as the finish, General Howard and I were the only two persons who were in the Nez Perce campaign from beginning to end. Some joined us later, and the entire command was stopped by order a day’s journey from the scene of the surrender. Of the small detachment with which Howard pushed on to find Miles, he and I were the only ones who had participated in the earlier part of the campaign. And now I am the only survivor of the little group which stood on the rolling hilltop at Snake Creek and watched Joseph come up to surrender. Therefore I feel it is somewhat of an obligation for me to give my own experiences in the Nez Perce War.

After the battle of the Clearwater, came skirmishes at the beginning of Lolo Trail, then the battle at Big Hole, where Gibbon was wounded; then the early morning attack at Camas Meadows, where Joseph ran off with our pack train and we, recovering only about half, had to stop at Henry Lake and send into Virginia City, Montana, for pack horses and wagons. Then we built the bridge across the Yellowstone River and brought over it the first wagons that had ever gone through the National Park. Joseph’s trail had let us so far through some of the most terrific fastnesses of the Rocky Mountains.

Howard had wired Sturgis to have his six or seven troops of the Seventh Cavalry watching for Joseph’s debouchments from the mountains somewhere in the neighborhood of Hart Mountain, for we judged by his line of trail and the trend of the water-courses and passes that he would have to descend from the mountains at that point. We tried to send messengers ahead of the Nez Perce to give Sturgis definite information of our coming, but not one of our couriers got through, all being killed by the Indians. Nevertheless it did not seem possible for Joseph to make the maneuver in this country which he had done at the eastern end of the Lolo Trail — that is, go over the hills and around the waiting enemy. I shall never forget the actual pass through which he made his exit into Clark Basin near Hart Mountain. It was the spout of a funnel — the dry bed of a mountain torrent, with such precipitous walls on either side that it was like going through a gigantic rough railroad tunnel. Had Sturgis remained at Hart Mountain in accordance with instructions, ready and watching, Joseph’s escape would certainly have been blocked. But in the night Joseph had sent a few of his young men quietly around Sturgis’ force toward Hart Mountain. There, at daybreak, they stirred up a great dust by tying sagebrush to their lariats and riding around furiously, dragging the bundles of brush along the ground. Sturgis thought Joseph’s whole body had got past him, and started in pursuit of the long dust trail, abandoning the mouth of the pass. When he saw it clear Joseph went through safely. The young men who had acted as decoys made a long circuit and joined Joseph out on the easy plains of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers.

At this time Howard sent a written order down the Yellowstone by boat to Miles at Fort Keogh and a duplicate overland by mounted messenger. I myself wrote this order, which was in substance as follows:

Joseph and his band have eluded Sturgis and he is now continuing his retreat toward British Columbia, and we believe is aiming at refuge with Sitting Bull. He is traveling with women and children and wounded at a rate of about twenty-five miles a day; but he regulates his gait by ours. We will lessen our speed to about twelve miles a day and he will also slow down. Please at once take a diagonal line to head him off with all the force at your command, and when you have intercepted him send word to me immediately and I will by forced marching unite with you.

I am not sure whether that order mentioned the fact that we had with us two old Indians whose daughters were in Joseph’s camp: Old George and Captain John, and an interpreter, Arthur Chapman, a Nez Perce squaw-man, in whom Joseph had great confidence. We believed that if Joseph could be stopped he would surrender without further resistance on our arrival. I do think there was some such information given to Miles in the order I wrote or verbally by messenger. Nevertheless the essential thing was to notify him of Joseph’s whereabouts, of which at this time he had no knowledge at all, the direction of his flight, and his rate of march, and also our intention of slowing down till we heard from Miles. My memory is clear on these particulars.

When General Howard left his own military department (Department of the Columbia), at the eastern end of the Lolo Trail, he sent General Sherman at Washington a telegram which I wrote. Its substance was:

Shall I continue pursuit of the hostile Nez Perces beyond the limits of the Department of the Columbia? And if so, what provision will be made for the subsistence of my troops, horse and foot?

In due time, and before we reached the Yellowstone, General Sherman’s reply reached us, which I remember was about as follows:

Pursue the Indians until captured or driven beyond the boundaries of the United States. When captured, care for them as prisoners of war in your own Department. Subsist on the country as the Indians do.

As the Indians were sweeping the country bare ahead of us, this last seemed a poor joke. But we did manage to subsist, although at times on very meager rations — and when tobacco ran out, it was tragic.

I mention these dispatches now, to show how thoroughly General Howard and all of us were affected by the words “When captured, care for them as prisoners of war in your own Department.” This meant Idaho, so far as the Indians were concerned. From that time on no one, including General Howard, had any other thought but that when the Indians were captured they would be taken back to Idaho.

This should be kept in mind when I come to the surrender, for it was Joseph’s claim that he was promised as a condition of the surrender that he and his people would be taken back to their own country.

Miles acknowledged the receipt of Howard’s order, and said he would at once set out on the diagonal line to intercept Joseph. The messenger returned and said that he had delivered the order to Miles and that Miles had immediately issued orders to his command, and made all necessary preparations that night, including rations, ammunition, horse feed and two howitzers, and had at daybreak set out at a rapid pace on the diagonal line which General Howard hoped would enable him to intersect the Indian line of march.

When General Howard was told of this rapid efficiency, he was as happy as a schoolboy, and said, “That is just like him! I knew we could depend on Miles.”

We lessened then our pace to about twelve miles a day in accordance with our communication to Miles, and so proceeded for a few days, following the Indian trail, until Howard felt certain that sufficient time had elapsed for Miles, with his mounted command, to have made the interception and to have sent word to him by mounted messenger. Meanwhile, Sturgis and his cavalry joined our command on the Musselshell, September 20th. Here we received word from Miles that he was in hot pursuit on the diagonal line indicated. Again Howard was jubilant. We continued at our leisurely pace for about a week and then received a dispatch from Fort Benton, addressed to either General Howard or Colonel Gibbon, to the effect that the Indians had crossed the Missouri at the mouth of the Musselshell and that Miles was closing in along the diagonal line of interception. We now pushed on rapidly and at Carrolton on the Missouri took the steamer Benton and in one day went up the Missouri to Cow Island, where the Indians had crossed. General Howard now began to worry about Miles, fearing he had been surrounded as Gibbon had been. He felt in view of all the information received it was ample time he had received word from Miles. But at Cow Island a messenger from Miles arrived, saying the Indians did not suspect his whereabouts and that he was closing in on the line of interception as planned. Howard estimated that by this time Miles should have met the hostiles, and he grew more uneasy; so with Miles’ messenger as guide he set out October 3rd accompanied by his two aides, who were his son Guy and myself, and seventeen men, including the two old Indians who had daughters in the hostile camp — Old George and Captain John — and Arthur Chapman, the Nez Perce squaw-man.

The wreck of the freighter’s train greeted us as we left the steamer. It was now very cold and we had only “buffalo-chips” for fuel. We bivouacked that night on the open prairie. Some of the men got sick from the villainous alkali water-melted snow, caught in buffalo wallows. At earliest daylight of the 4th of October we resumed our quest of Miles, still following the Indian trail. In the afternoon we saw a man at a distance across the prairie, evidently puzzled by our appearance. General Howard sent a couple of our scouts to bring him in. He turned out to be a bearer of mail and dispatches for Miles from Miles’ post at Fort Keogh, and was trying to find him. He was a frontiersman called Slippery Dick or “Liver-Eating Johnson” — because, by his own story and popular report, he was supposed to have eaten a piece of the liver of an Indian whom he had killed and scalped, thereby following the tradition of the Indians, that if one ate a part of the heart or liver of an enemy, he would acquire all the bravery of the dead man.

We continued our march with this liver-eating recruit. I, with two of our scouts, branched from the direct line of march, and went off on the prairie after a herd of buffalo. I shot one, and found that by chance I had killed what is known as a “Silk Robe” buffalo, that is, an animal whose coat was nearly as soft as beaver-fur. It was a very rare and valuable specimen, and I was anxious to preserve it. The two scouts set to work skinning the buffalo, and they had just finished and the hide had been rolled up by one of the scouts and loaded on his pommel, when one of the soldiers came riding back at full speed, saying that General Howard ordered us to close up — there were Indians ahead. Regretfully we threw the hide to the coyotes and rode to join our party.

Against the snow of Bear Paw Mountain some ten miles away we saw what seemed to be a line of black ants crawling down the butte. They turned out to be some of Miles’ Cheyenne scouts. While I was absent, one, or as I think two, scouts overtook us and said they were messengers from Miles to Sturgis who had been sent to notify the latter that the Nez Perce had been encountered.

Later I was told by other scouts they had been sent to notify Howard also, and having missed him, had reported to Colonel Edwin Mason, next in command.

After the surrender there was so much bitterness toward Miles in the Howard command and so many stories afloat that my memory has been confused. The last message from Miles that I remember had been received at Cow Island on about September 27th, and I know Howard had been worried because he did not hear further. One explanation may be that the messengers went first to Sturgis, then to Howard’s command, but he having pushed on ahead, they reported to Colonel Edwin Mason.

When Howard met Miles at Bear Paw he said, “Why didn’t you let me know? I was afraid you had met Gibbon’s fate.” When I told Howard in private conversation, as I shall relate later, that I distrusted Miles because he had failed to notify us to hurry, Howard defended Miles. Nevertheless I do not remember Miles’ telling me messengers had been sent to Howard, even though they had missed him. There was a prevalent opinion that Miles did not want Howard to close up for fear Howard, as senior officer, would by operation of military law, supersede him in full command. I think in all this confusion the proper solution is to accept Miles’ own statement that he did send messengers to Howard, and to assume that the messengers who overtook us had been to Howard’s camp but missed him. After all these years I would not want to put my memory forward as exact.

Still it would be interesting to know the exact purport of Miles’ messages. If the one to Sturgis asked him to come at once to his support and relief, Sturgis with his fresh cavalry should have arrived on the scene at least as soon as the returning messengers, but in fact these troops never arrived on the Bear Paw field at all, nor made any effort in that direction, nor seemed to be expected. If the message to Howard was to close up by forced marches as agreed, Colonel Mason would have done this, and if Howard’s personal presence was desired why did Miles meet him so coldly, and in his official report make not the slightest allusion to his personal presence nor to the important part played by the two old Indians and Chapman, the interpreter? They would have vouched for Howard’s presence and the proximity of his whole command — facts that really brought about the surrender. Could it have been possible that Colonel Miles did not wish Howard to be present (lest he oust him from command and share credit for the surrender)? As Miles’ messengers were sent off immediately after the first attack it would seem Miles anticipated victory, and that the messages were to that effect, declaring any junction of forces, either by Sturgis or Howard, unnecessary. Every commander who had surprised these Nez Perce — Perry, Gibbon and Sturgis — had confidently expected that after the first assault all would be over, since such had been their experience with all other Indians they had met. If Miles also shared this confidence and sent, immediately after the attack, messages anticipating victory and showing any junction of forces to be unnecessary, then the failure of Mason to push on to overtake Howard and his small escort, and above all the failure of Sturgis ever to arrive on the scene are understandable.

With the above explanation to show that I was very likely wrong in having held that Miles did not send back some message to Howard, I shall go on with my story as I remember the incidents. This particular incident is not important. What are important as historical facts are the conversations between Howard and Miles in Miles’ tent at Bear Paw and between Howard and myself at that time and the subsequent train of events and incidents. As to all these my memory is absolutely clear; they were burned in.

As we approached Miles’ camp that cold snowy evening it was dark, and we saw the flashes of the rifles from the rifle pits on both sides. Miles met us with his adjutant, Lieutenant Oscar Long, and an orderly and perhaps two or three soldiers all mounted. General Howard dismounted and we all followed his example. Howard advanced toward Miles, who had also dismounted, and Howard held out his hand, saying very delightedly “Hello Miles! I am glad to see you. I though you might have met Gibbon’s fate. Why didn’t you let me know?”

Miles made no answer to this but replied with a cold formal greeting and asked the general to come to his tent while he was having a separate tent prepared for him. Howard motioned to the Indians Old George and Captain John, and said, “Miles, I have two old Nez Perce Indians here who have daughters in the hostile camp. I have brought them as witnesses and negotiators. Also Arthur Chapman there has lived with these Indians and they trust him. I wish you would have them all taken care of.”

As I remember it Miles told Long to take care of them, keeping the Indians under guard, and they all went off accompanied by the General’s son, Lieutenant Guy Howard. Miles and Howard went on to Miles’ tent, I following.

General Howard said as we entered, “Lieutenant Wood always occupies my tent with me; he is my aide-de-camp and is adjutant general in the field for my command.” Colonel Miles nodded in my direction at this, and then General Howard plunged earnestly into the heart of the matter:

“Miles, you have given me the sort of assistance I wanted, and what I expected of you. You stopped those Indians, and I intend to see you have the credit for it. I know you are ambitious for a star (the insignia of a brigadier-general) and I am going to do all I can to help you. We will have a surrender tomorrow. These old Indians will tell Joseph and the others that I am here on the spot and my entire command is only one day’s march away which they will be by the time we are through negotiating tomorrow. We will have a surrender, beyond shadow of a doubt — and I repeat — you shall receive the surrender. Not until after that will I assume command. Tomorrow morning you and I will talk things over.”

Colonel Miles’ entire manner changed; he became cordial, thanked the General for all he had said, and added “You must be very tired. We will meet in the morning to arrange matters.”

When we left the tent and entered the one assigned to us, I said to General Howard, in substance:

“General, I am a little surprised at what you have just said, and feel as your aide I ought to speak very freely, as the confidence you have in me deserves. You have just said that you are going to help Miles to a star. I feel that is very impulsive and may lead to some feeling on Gibbon’s part. He is a much older man of the Civil War than Miles and we have left him behind us, wounded at the Big Hole battle. He also is an aspirant for a star, and his Civil War record gives him a great superiority over Miles. But, of course, Miles has a father-in-law, Senator Sherman, and his uncle-in-law, General Sherman, and other political influence. But that is not exactly what I am troubled about. You have told Miles you are not going to assume command until after the surrender. Now, the Articles of War expressly say when two commands meet, the senior officer must assume command of all, so I do not think this chivalrous act of yours will have any recognition in military law, and, if there is any criticism hereafter, you will certainly have to bear the responsibility.”

“Yes, yes,” he said, “I know that. But this is an act of generosity not uncommon between commanders, and I am willing to bear the responsibility, as of course I must.”

“Well,” I replied, “General, the chief thing is your command, in which is my own regiment. They have followed you from the Battle of the Clearwater and across the Bitter Root Mountains and the Rockies, — a terrific march, filled with hardships, and now, only a day’s march away, you halt them there and deprive those ragged and footsore foot troops and the jaded and worn out cavalry of their right to be in at the death.”

“Well,” he said, “that touches me very deeply, but we will adjust it so that my own immediate command will be given full credit. I will have Miles in his report say that my entire command was present and assisting at the surrender which in a military sense they are. As you say, they are only one march off. Joseph will know all this tomorrow from Captain John and Old George and Chapman, and it will be because of the presence of myself and my command that they will see how hopeless is further conflict. So my immediate command will produce the surrender. In a military sense it is present on the ground.”

“Well,” I said, “all right. I am not convinced, but I have nothing more to say. I do not trust Colonel Miles. I am sorry to say it, but I do not trust him. When you asked him this evening when you first met, “Why didn’t you let me know, Miles?” he didn’t answer, and you hurried on to tell him he had given you the assistance you had expected of him, and he never answered. He knows the Articles of War, and I think he deliberately refrained from sending you a report, because he knew that by forced marching in one day, or two at the most, it would place you here on the spot and in command by the fixed rules of military law. Of course he could not foresee your doing this chivalrous deed — letting him receive the surrender and taking all the credit.”

I give this as I remember it and it is substantially accurate. It was too important and has been too often repeated to be forgotten. When I had concluded General Howard put his left hand on my shoulder (he had lost the right at Fair Oaks) and said:

“Wood, you are wrong to distrust Miles. Why, I would trust him as fully as I would you. He was an aide-de-camp on my staff during the Civil War, just as you are now. I got him his first regiment. I would trust him with my life.”

This ended the discussion. The bedding was brought in and we went to sleep. Next morning General Howard, his son Guy, I, Colonel Miles and his adjutant Lieutenant Long, the interpreter Arthur Chapman, and the two old Indians, Old George and Captain John, all met at a rather commanding spot on the rounding brow of a hill opposite to one where were the rifle pits dug by the trapped Indians. In the winding ravine between lay their camp, but now all its inmates were dug into the hill for protection. After a little discussion between General Howard and Colonel Miles which I did not hear, as I, Long and Guy Howard were off to one side, Chapman was called and was told to tell the two old Indians to go in and assure Joseph and White Bird and all the rest, that General Howard himself was here, ready to be their friend; that his whole command was only one march away and if necessary would be brought up and the fight resumed, which could now have only one end. Chapman was also told that the old men could say that if the band surrendered they would be supplied with food and blankets and otherwise taken care of. All the warriors would be considered as honorable prisoners of war, and there would be no trials or executions for anything done in the past. I am sorry I do not remember whether it was distinctly said that they would all be returned to the country of their people in Idaho. I am very sure nothing was said about their being returned to their homes in the Wallowa or the Imnaha valleys, because General Howard well knew that the government had given its final decision in that matter and that those valleys would never again be Nez Perce territory. It was on this very decision of the government that General Howard had held his last council with Joseph and the other chiefs, at the conclusion of which they had agreed to give up their claims to the Wallowa and Imnaha valleys and to take allotments in the existing Nez Perce reservation in Idaho. But I am very sure that no matter what the exact words were, everyone there, including General Howard, understood and fully expected the final disposition to be the return of these prisoners to the Department of the Columbia — that is to say, to the Lapwai reservation in Idaho.

I must here recall attention to the telegram of Sherman’s, mentioned above, to the effect that the Indians if captured were to be taken to the Department of the Columbia (which meant Idaho). Everybody took this as an accepted fact, including the old Indians, Captain John and Old George, and the interpreter, Chapman. It was one of those accepted facts which become part of a contract or agreement, as much as if definitely expressed in words. Colonel Miles had had two conferences with Joseph before we arrived. In these conferences he had promised in clear terms that if Joseph surrendered, he and his people would be returned to their own country, and I feel that if Miles promised this at any time, it unavoidably became a condition of any surrender Miles received as full commander.

I will a little later quote another order I wrote at General Howard’s dictation, which will show how after the surrender he himself was still firmly of the opinion that he not only might but that he must return the Nez Perce to the Department of the Columbia. Every excuse made for not doing so — that it was for the welfare of the Indians, that the whites would take revenge on them, that it would bring on another Indian war, though perhaps good reasons in a way — clearly broke faith with the Indians and repudiated one of the conditions of the surrender.

Without digressing further, let me say that on that same day, the 5th of October, the ground covered with a light fall of snow, the surrender was agreed on. About an hour or so before sunset there came from the ravine below, up to the knoll on which we were standing, a picturesque and pathetic little group. Joseph was the only one mounted, and he sat, his rifle across his knees at each side of his horse talking earnestly. Slowly they mounted to where we stood at the top. General Howard and Colonel Miles were grouped together, and a little retired, myself, Lieutenant Howard, Lieutenant Long, and further back an orderly and Arthur Chapman, the interpreter. Still further away, at some little distance, a courier stood at the head of his horse, holding loosely the bridle while the horse pawed the snowy ground. When the Indians reached the summit those on foot stopped and went back a little, as if all was over. Then, nothing but silence. Joseph threw himself off his horse, draped his blanket about him, and carrying his rifle in the hollow of one arm, changed from the stooped attitude in which he had been listening, held himself very erect, and with a quiet pride, not exactly defiance, advanced toward General Howard and held out his rifle in token of submission. General Howard smiled at him, but waved him over to Colonel Miles, who was standing beside him. Joseph quickly made a slight turn and offered the rifle to Miles, who took it. Then Joseph stepped back a little, and Arthur Chapman stepped forward so as to be between Joseph and the group of two-Howard and Miles. I was standing very close to Howard, with a pencil and a paper pad which I always carried at such times, ready for any dictation that might be given. Joseph again addressed himself to General Howard, as was natural, for he had had several councils with Howard, including the last one which led to the war. He said (Chapman interpreting):

“Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before — I have it in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Too-hul-hul-sit is dead. Looking Glass is dead. He-who-led-the-young-men-in-battle is dead. The chiefs are all dead. It is the young men now who say ‘yes’ or ‘no.’ My little daughter has run away upon the prairie. I do not know where to find her-perhaps I shall find her too among the dead. It is cold and we have no fire; no blankets. Our little children are crying for food but we have none to give. Hear me, my chiefs. From where the sun now stands, Joseph will fight no more forever.”

(He-who-led-the-young-men-in-battle was his brother, Alikut.)

As Joseph finished he drew his blanket over his head and turned to walk away to where his friends had remained standing, but I motioned to him to wait. Colonel Miles took a paper from Lieutenant Long and stepped aside with General Howard and showed it to him. General Howard read it attentively, then looked up and smiled and said, “That is all right, Miles.” Colonel Miles then walked away with Lieutenant Long, and General Howard, now assuming command said to me, “Mr. Wood, take Chief Joseph as prisoner of war into camp; see that he is well treated, not in any way annoyed, but carefully guarded against escape.” I had Chapman translate this to Joseph and I nodded pleasantly to the chief and tried to look, at least, as if it were all friendly. I beckoned him to come with me, and he promptly came forward, and we started to walk back. I noticed that Colonel Miles and Lieutenant Long, who had gone together to where the courier stood at the head of his horse, did not at once dispatch the message which had been shown to Howard, but that with the courier they were slowly walking back into camp. Presently I saw the courier galloping away. Colonel Miles returned and joined General Howard. They overtook me and Chief Joseph just as we reached the tent assigned to him. General Howard told Miles he had put me in charge of the prisoner, and he would be glad if Miles would issue orders to have him carefully guarded. When I had seen Joseph into his tent and had said to him through Chapman that we wished to make him very comfortable and if there was anything he wanted, or anyone he wanted to see, or any messages he wanted to send, he was to communicate his wishes to Chapman. I told him I myself would see him again. For General Howard and all the soldiers I wished him good luck and hoped his troubles were over, and then left him. It will be observed that true to Indian custom, Joseph had not spoken for White Bird. That night this chief with his family and a few of his band escaped and finally joined Sitting Bull in Canada. General Howard maintained that in permitting this Joseph had violated the terms of surrender, and so the government was not bound to return the Indians to the Department of the Columbia.

I had written in lead pencil Joseph’s speech as he gave it through Chapman, but eventually I gave the original to the adjutant general of the army, at his request, because he said he had in his archives the speeches of Chiefs Logan, Red Jacket and one other of the great Indian chiefs I forget the name-and he would like to add this speech of Joseph’s to the collection. I gave it to him, and as it was not long I made a copy immediately. Later, after I had resigned from the army, and was on one of my visits to Washington to appear before the Supreme Court, I went into the War Department and as a matter of curiosity asked to see this lead-pencil memorandum which I had made, as I had lost my own copy. The clerks made diligent search for it, but the then adjutant general told me it had disappeared. I have done my best now to reconstruct it from memory, but it will be found correctly given in the account of the surrender which I wrote for a Chicago newspaper and in the article I later wrote for the Century Magazine.

I wrote in these articles all that I here say in criticism of Colonel Miles and more, and all that I will hereafter say in this introduction. Also, I freely criticized Miles to my former fellow-officers stationed at Vancouver Barracks, where Miles, now a general, was located in command of the Department of the Columbia. I was then practicing law in Portland, Oregon, just across the Columbia from Vancouver, Washington, and General Miles and I frequently met at formal functions, but he never accused me of doing him an injustice. Indeed, he never alluded to the matter. This present comment is therefore not as if I for the first time censured one whose lips were sealed in death.

General Howard almost immediately after Joseph’s surrender prepared to leave with his command for the steamer Benton, ordered to wait for us on the Missouri. The river was beginning to run low by reason of the freezing nights, and both the captain of the steamer and General Howard were exceedingly anxious to be off before navigation closed. As a part of his final adjustment of matters relating to the Indians, Howard issued an order to Colonel Miles, which I wrote. It was substantially as follows:

Col. Nelson A. Miles, etc.