About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Author: Eugene Tyler Chamberlain

Date:1893

Annotation: Hawaiian annexation.

After a century of American rule, many native Hawaiians remain bitter about how the United States acquired the islands, located 2,500 miles from the West Coast. In 1893, a small group of sugar and pineapple-growing businessmen, aided by the American minister to Hawaii and backed by heavily armed U.S. soldiers and marines, deposed Hawaii’s queen. Subsequently, they imprisoned the queen and seized 1.75 million acres of crown land and conspired to annex the islands to the United States.

On January 17, 1893, the conspirators announced the overthrow of the queen’s government. To avoid bloodshed, Queen Lydia Kamakaeha Liliuokalani yielded her sovereignty and called upon the U.S. government “to undo the actions of its representatives.” The U.S. government refused to help her regain her throne. When she died in 1917, Hawaii was an American territory. In 1959, Hawaii became the 50th state after a plebiscite in which 90 percent of the islanders supported statehood.

The businessmen who conspired to overthrow the queen claimed that they were overthrowing a corrupt, dissolute regime in order of advance democratic principles. They also argued that a Western power was likely to acquire the islands. Hawaii had the finest harbor in the mid-Pacific and was viewed as a strategically valuable coaling station and naval base. In 1851, King Kamehameha III had secretly asked the United States to annex Hawaii, but Secretary of State Daniel Webster declined, saying “No power ought to take possession of the islands as a conquest…or colonization.” But later monarchs wanted to maintain Hawaii’s independence. The native population proved to be vulnerable to western diseases, including cholera, smallpox, and leprosy. By 1891, native Hawaii’s were an ethnic minority on the islands.

After the bloodless 1893 revolution, the American businessmen lobbied President Benjamin Harrison and Congress to annex the Hawaiian Islands. In his last month in office, Harrison sent an annexation treaty to the Senate for confirmation, but the new president, Grover Cleveland, withdrew the treaty “for the purpose of re-examination.” He also received Queen Liliuokalani and replaced the American stars and stripes in Honolulu with the Hawaiian flag.

Cleveland also ordered a study of the Hawaiian revolution. The inquiry concluded that the American minister to Hawaii had conspired with the businessmen to overthrow the queen, and that the coup would have failed “but for the landing of the United States forces upon false pretexts respecting the dangers to life and property.” Looking back on the Hawaii takeover, President Cleveland later wrote that “the provisional government owes its existence to an armed invasion by the United States. By an act of war…a substantial wrong has been done.”

President Cleveland’s recommendation that the monarchy be restored was rejected by Congress. The House of Representatives voted to censure the U.S. minister to Hawaii and adopted a resolution opposing annexation. But Congress did not act to restore the monarchy. In 1894, Sanford Dole, who was beginning his pineapple business, declared himself president of the Republic of Hawaii without a popular vote. The new government found the queen guilty of treason and sentenced her to five years of hard labor and a $5,000 fine. While the sentence of hard labor was not carried out, the queen was placed under house arrest.

The Republican Party platform in the presidential election of 1896 called for the annexation of Hawaii. Petitions for a popular vote in Hawaii were ignored. Fearing that he lacked two-thirds support for annexation in the Senate, the new Republican president, William McKinley, called for a joint resolution of Congress (the same way that the United States had acquired Texas). With the country aroused by the Spanish American War and political leaders fearful that the islands might be annexed by Japan, the joint resolution easily passed Congress. Hawaii officially became a U.S. territory in 1900.

When Capt. James Cooke, the British explorer, arrived in Hawaii in 1778, there were about 300,000 Hawaiians on the islands; however, infectious diseases reduced the native population. Today, about 20 percent of Hawaii’s people are of native Hawaiian ancestry, and only about 10,000 are of pure Hawaiian descent. Native Hawaiians were poorer, less healthy, and less educated than members of other major ethnic groups on the islands.

Sugar growers, who dominated the islands’ economy, imported thousands of immigrant laborers first from China, then Japan, then Portuguese from Madeira and the Azores, followed by Puerto Ricans, Koreans, and most recently Filipinos. As a result, Hawaii has one of the world’s most multicultural populations.

In 1993, a joined Congressional resolution, signed by President Bill Clinton, apologized for the U.S. role in the overthrow. The House approved the resolution by voice vote. The Senate passed it 65 to 34 votes.

Document: Daniel Webster, Secretary of State, on July 14, 1851, wrote to Luther Severance, representing the United States at Honolulu:

The Government of the United States was the first to acknowledge the national existence of the Hawaiian Government, and to treat with it as an independent state. Its example was soon followed by several of the Governments of Europe; and the United States, true to its treaty obligations, has in no ease interfered with the Hawaiian Government for the purpose of opposing the course of its own independent conduct or of dictating to it any particular line of policy. In acknowledging the independence of the Islands, and of the Government established over them, it was not seeking to promote any peculiar object of its own. What it did, and all that it did, was done openly in the face of day, in entire good faith, and known to all nations. . . . But while thus indisposed to exercise any sinister influence itself over the counsels of Hawaii, or to overawe the proceedings of its Government by the menace or the actual application of superior military force, it expects to see other powerful nations act in the same spirit.

Mr. Webster went further, directing Mr. Severance to return to the Hawaiian Government an act of contingent surrender to the United States, placed in his hands by that Government, and specifically warned Mr. Severance against encouraging in any quarter the idea that the Islands would be annexed to the United States.

Up to January 16, 1893, the broad principles laid down in Mr. Webster’s quoted words were not only the rule of conduct for the Government of the United States in its relations with the Government of Hawaii; but they were also recognized by those who desire, as well as by those who do not desire, the annexation of the Hawaiian archipelago to this country. The state papers of Secretary Marcy and Secretary Blame, and the published utterances of other distinguished citizens of the United States who have regarded annexation as the ultimate and desirable destiny of these islands of the Pacific, will be searched to no purpose for indications of a belief that annexation should be brought about otherwise than in fidelity to treaty obligations, openly in the face of day, in entire good faith and known to all nations, and without the menace or actual application of superior military force. A belief to the contrary is so repugnant to the traditions and temper of the American people, and so clearly involves adherence to the theory of insular colonial expansion by conquest, that one may safely assert it will find scant favor among the people of the United States.

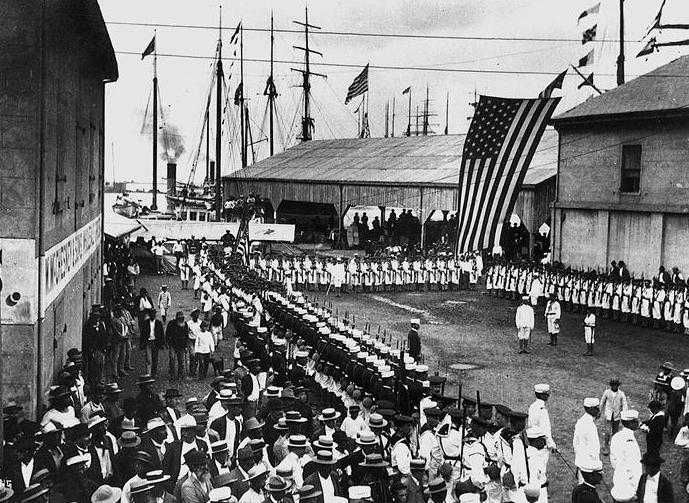

The dethronement of Queen Liliuokalani and the establishment of an oligarchy on the island of Oahu, “until terms of union with the United States of America have been negotiated and agreed upon,” were effected on the afternoon of Tuesday, January 17, 1893, in the presence of a considerable body of the naval forces of the United States, armed with Gatling guns, and stationed in the immediate vicinity and in plain sight of the Palace and Government Building, where the so-called revolution was consummated.

The local causes of this so-called revolution, remote and proximate, are relatively immaterial to the United States. They, with the general issue of annexation, dwindle before the question: What were the purpose and the effect of the presence of the forces of the United States in Honolulu on January the sixteenth and seventeenth?

The recognized government of a nation with which we were at peace had officially notified Minister Stevens, our representative, of its ability to preserve order and protect property. The Vice-Consul-General of the United States, Mr. W. Porter Boyd, testifies that no uneasiness was felt at the consulate, and that the landing of the troops was a complete surprise to him. All the signs of street life betokened good order, and, soon after the blue-jackets had trailed their artillery through the streets, the population of Honolulu was enjoying the regular Monday evening out-of-door concert of the Hawaiian Band. The landing of the troops was promptly followed by the protests of the proper authorities of the kingdom and the island, transmitted officially to Minister Stevens. No evidence has been presented to Commissioner Blount to show that there was any apprehension or any desire for the presence ashore of the men of the Boston under arms, except on the part of the members of the Citizens Committee of Safety. The matter was not referred to at the mass meeting of the foreign population, organized by that committee, and held but a few hours before the troops landed.

The Committee of Safety, at whose request Mr. Stevens summoned the troops, did not prefer that request as American citizens. It could not, for only five of its thirteen members owed allegiance to and were under the protection of the United States. By the admission of several of their own number to Mr. Blount, they were engaged in plotting secretly the overthrow of the government and the establishment of themselves in power until they could transfer the Islands to the United States, and Minister Stevens was in their full confidence at the time they asked for, and he ordered, the lauding of the troops. They had been threatened with arrest by the government they planned to overthrow, and he had promised to protect them. The troops of the Boston were the only means he had of keeping good that promise, and he did not scruple to use them for it. But even to the thirteen engaged in the plot the danger of arrest was not so imminent as to deter them from requesting Mr. Stevens not to land the troops too soon for their purposes. Mr. W.0. Smith, the attorney-general of the Provisional Government and a leader in the committee, testifies that at a conference on Monday afternoon, at four o’clock, “our plans had not been perfected, our papers had not been completed, and, after a hasty discussion–the time being short–it was decided that it was impossible for us to take the necessary steps, and we should request that the troops be not landed until the next morning, the hour in the morning being immaterial–whether it was nine, eight, or six o’clock in the morning–but we must have further time to prevent bloodshed.” Nevertheless the “Boston’s” men landed at five o’clock, Mr. Stevens being apparently the only man on the Island of Oahu who deemed their presence necessary at that time.

To keep pace with Mr. Stevens haste the Committee of Safety met secretly a few hours later and selected Judge Sanford B. Dole as the civil head of their oligarchy, and Mr. John II. Soper, a citizen of the United States, as the head of its military forces, then in existence only in the imagination of the conclave. Mr. Soper admits that he did not agree to accept the command of the provisional “army” until he was assured that Minister Stevens would recognize the Provisional Government on Tuesday. On their part both Judge Dole and Minister Stevens apparently did not have entire confidence in the prowess of “General” Soper, as witness the following letter to Judge Dole the next day:

U. S. Legation, Jan. 17, 1893. Think Captain Wiltse will endeavor to maintain order and protect life and property, but do not think he would take command of the men of the Provisional Government. Will have him come to the Legation soon as possible and take his opinion and inform you soon as possible.Yours truly, John L. Stevens.

The purpose of the presence of the blue-jackets, in the minds of the committee that asked for it, is summed up in the admission of Judge Dole that when the troops were first furnished they could not have gotten along without their aid, and of Mr. Henry Waterhouse of the Committee:

We knew the feeling of those who were in power then–that they were cowards–that by going up with a bold front and they supposing that the American troops would assist us, that would help us out.

The forces of the United States, thus brought ashore against the protest of a friendly Power, at the request of men engaged in a plot to overturn that Power, were stationed, remote from the residences of Americans, less than a hundred yards from the Government Building, designated by Minister Stevens as the place in which the Provisional Government should be established to secure his recognition, and in plain sight of the Queens palace windows. Admiral Sketrett sums up the disposition of the forces thus:

The American troops were well located if designed to promote the movement for the Provisional Government, and very improperly located if only intended to protect American citizens in person and property.

The Queen was dethroned and the oligarchy established by proclamation, read by a citizen of the United States, shortly before three o’clock, and recognized, in the name of the United States, by Minister Stevens before it was in possession of any point held in force by the Queen’s government. With more prudence Captain Wiltse, in command of the “Boston,” declined to recognize it until it came into possession of the military posts of the Queen, as it did by her voluntary surrender of them early in the evening. Her surrender was in terms to the superior force of the United States, and until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon the facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representative, and on this understanding it was accepted by the junta.

On February 25, 1843, King Kamehameha III ceded the Hawaiian Islands to Lord George Paulet under duress of the guns of Her Majesty’s ship “Carysfort,” subject to review by the government of Queen Victoria, and the British flag was raised over Honolulu. On July 31 of the same year Rear Admiral Richard Thomas, representing the Queen, declined to accept the cession, and recognized the King as the lawful sovereign of the Islands, stating that this act of restoration should be accepted by the King

as a most powerful and convincing proof not only of the responsibility he is under to render immediate reparation for real wrongs committed upon British subjects or their property, but also of the importance which attaches to the maintenance of those friendly and reciprocally advantageous relations which have for so many years subsisted between the two nations.

The people of Hawaii have dedicated one of the public squares of Honolulu to the memory of this just and generous restoration of their national life.

The questions raised by Commissioner Blount’s report—and the statement of facts given in these pages rests on the testimony of annexationists–take precedence of any question of territorial expansion. Through the action of their representative the United States were placed on January16 and 17 in the position of armed invaders of a friendly state, giving countenance and moral support to a plot to overturn a Government, which could not otherwise have succeeded and would not otherwise have been attempted. The character of that Government does not enter into the question of the observance of our treaty obligations to it or into that consideration which is due to the weak from the strong in the mind of every American.

Eugene Tyler Chamberlain