About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

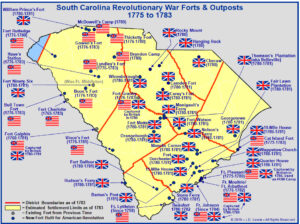

Forts were often already positioned in important locations or constructed at strategic points on the landscape. These locations were often where waterways or roads converged. They were built to defend these travel ways or to defend nearby towns and cities. Forts often dictated the military strategy of both sides.

At the start of the Revolutionary War, the American continent was already dotted with forts that had been constructed as recently as the French and Indian War fifteen years prior. Among these forts were large masonry forts like Fort Ticonderoga. Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York was manned by a small force of British soldiers when the war broke out in April of 1775. On May 10, 1775, Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen captured the fort and its garrison without firing a shot. This proved to be important, as that winter Colonel Henry Knox moved the artillery from Ticonderoga overland to Cambridge, Massachusetts. This artillery proved to be decisive in driving the British from the city of Boston in 1776.

Another fort that was a relic of the French and Indian War that found new use was Fort Stanwix in western New York. Rather than a masonry fort, this was an earthen and timber structure. In 1777, a detachment of British forces laid siege to the American held fort. The Americans held out and after fear that American reinforcements were heading to relieve the American garrison, the British broke off the siege and fell back.

Early in the war, though, forts were quickly constructed where they would be needed to protect armies. In June of 1775, American soldiers fortified Breed’s Hill outside of Boston and placed an earthen redoubt or small fort on the top of the hill. The British assaulted the position but were shot down in large numbers. Only after losing hundreds of soldiers were the British successful in capturing the position.

In South Carolina, forts were constructed to defend the city of Charleston from a British naval attack. On Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina troops built a large fort made from local abundant resources: palmetto trees and sand. When British warships attacked the half-finished fort in June of 1776, the softwood of the palmetto tree absorbed the shock of British cannonballs, and the Americans drove the Royal Navy back. To this day, the symbol of the palmetto tree still graces the flag of South Carolina for the role it played in the battle of Sullivan’s Island.

One of the most important fortified positions in North America was at West Point, New York. It was often described as “the key to the continent.” In addition to the land fortifications, a large naval chain was constructed to span the Hudson River to prevent British ships from navigating the water. In 1780, American General Benedict Arnold betrayed the United States and conspired with the British to capture the important fortifications at West Point. The plot ultimately failed but displayed the importance of the position and forts at West Point.

To build these forts and fortifications, both armies used engineers to layout the design and construction using the latest military science. When the war broke out in 1775, there were very few Americans who had the engineering education and military understanding of how to construct forts and fortifications. The French were well known for their prowess in designing forts and both sides often used their methods in designing and building forts and fortifications. European volunteers, such as Polish engineer Thaddeus Kosciuszko, joined the American army to help with the construction of forts. Kosciuszko would play an important role in building American fortifications at battlefields across the continent during the war. In addition to fortifying important locations, Kosciuszko would travel with the Continental Army and help with building fortifications while the army was on campaign.

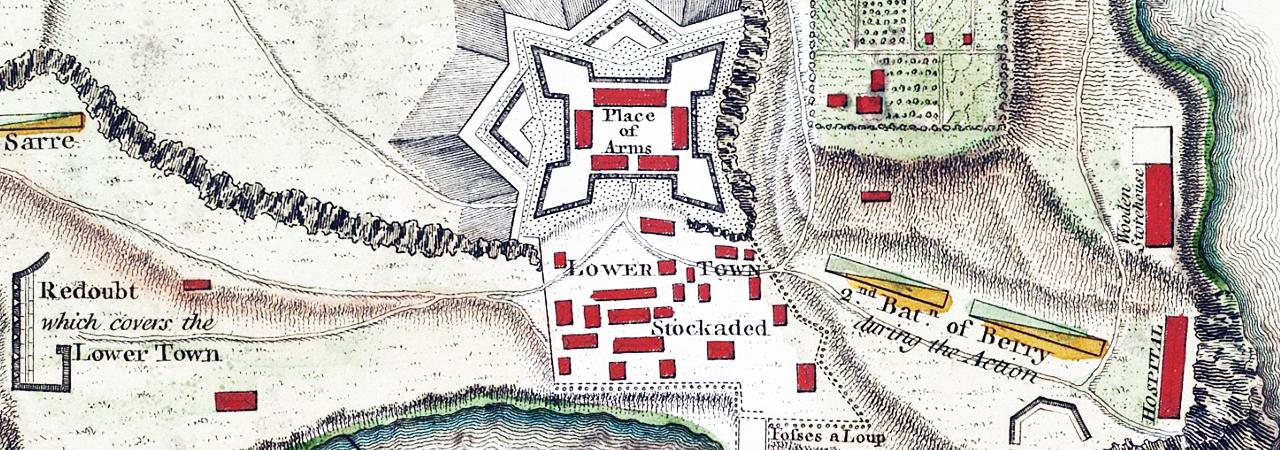

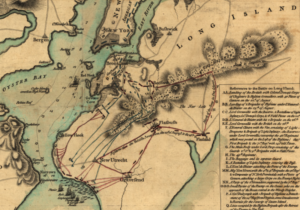

Armies often built numerous earthworks while on campaign. These earthworks followed a similar pattern in both armies. They would often have redoubts at locations of importance and then would connect the redoubts with earthen trenches. Soldiers and laborers would dig in the ground creating a dry moat and then would throw the dirt up to create a rampart. Outside of the dry moat they would place tangled tree branches that was called abatis that would act as an early form barbed wire and could entangle attacking troops. Often into the walls of the fortification they would drive large pieces of timber that had sharpened ends called fraises. Any troops assaulting the fortification would have to trudge through the abatis, drop into the dry moat and then make their way through the fraises to get over the ramparts, all the while under a galling fire from cannons and muskets. Both sides used sappers and miners for attacking entrenched positions. It was their job to move in the van of the assaulting column with axes and cut up these defenses to make holes for assaulting infantry.

At Boston, Charleston and Yorktown, thousands of yards of earthen fortifications were constructed by both armies during the sieges there. The final major battle of the Revolutionary War witnessed a massive creation of earthworks across the battlefield. At Yorktown, General Lord Cornwallis built numerous redoubts and trenches to defend his army. As the French and American troops arrived, they too constructed numerous earthen trenches called parallels (as they ran parallel to the British lines). They used this method to move closer and closer to the British lines to bombard their army with artillery. The final climactic action of the Revolutionary War occurred when American and French troops assaulted two British redoubts with bayonets only.

Ultimately, the linear tactics of battlefield warfare in the 18th century dictated that forts and fortifications were important and decisive components of warfare. Many of the same tactics and fortifications would continue to be used by militaries up to and through the American Civil War. In some cases, such as at Yorktown, the same earthworks used by the Revolutionary War soldiers were used by Civil War soldiers almost a hundred years later, displaying the universal importance of forts and fortifications, not only in the Revolution but in military history.