About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Born in Savannah, Georgia on January 21, 1813, Fremont was one four major generals appointed by President Lincoln, he was easily the most celebrated. As a Union general, Fremont’s major Civil War contribution was more political than military when he focused Union attention on the role emancipation should play in the North’s war policy.

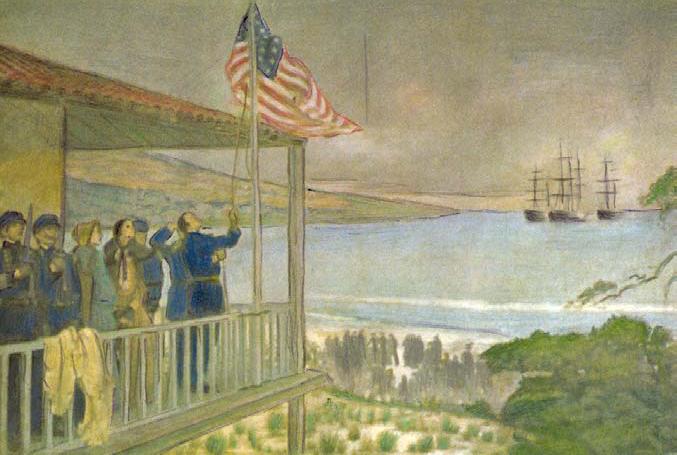

The magnetic and legendary “Pathfinder” became a national hero early in life for his trailblazing exploits in the Far West. A leader in wresting California from Mexico, he served as one of the state’s first senators and got rich in the Gold Rush. Fremont’s popularity and his antislavery position were equally instrumental in his being chosen the Republican Party’s first presidential nominee in 1856, the youngest man yet to run for the office. With Southern states threatening secession if he were elected, Fremont’s loss to James Buchanan forestalled disunion for another four years.

In Europe at the outbreak of the Civil War, he purchased a cache of arms in England for the North on his own initiative and returned to America. Abraham Lincoln, mostly for political reasons, appointed him major general in May 1861, placing him in command of the precarious Department of the West. Based in St. Louis, Fremont spent more energy fortifying the city and developing flashy guard units than equipping the troops in the field. His forces suffered several losses, particularly a major defeat at Wilson’s Creek that August.

Attempting to gain a political advantage in the absence of a military one, Fremont, in an unprecedented and unauthorized move, issued a startling proclamation at the end of the month declaring martial law in Missouri and ordering that secessionists’ property be confiscated and their slaves emancipated. The action was cheered by antislavery Republicans, but Lincoln, concerned that linking abolition to the war effort would destroy Union support throughout the slave-holding border states, asked Fremont at the very least to modify the order.

The Pathfinder refused, sending his wife, the politically influential daughter of former Senate leader Thomas Hart Benton, to Washington to talk to the president. Displeased with Fremont’s effrontery, Lincoln revoked the proclamation altogether and removed him from command. Pressure from his fellow Republicans forced Lincoln to give the popular Fr6mont another appointment, and in March 1862 he was named head of the army’s new Mountain Department, serving in Western Virginia.

Over the following two months, he endured several crushing losses against Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson during the Confederate general’s brilliantly successful Shenandoah Valley Campaign. After a military reorganization placed him under the command of former subordinate John Pope, Fremont angrily resigned his post, never to receive a new Civil War appointment.

In 1864, however, he began another presidential bid with the backing of a cadre of Radical Republicans, but withdrew from the race in September and threw his support to Lincoln after a rapprochement in the party. When he lost most of his fortune by the end of the war, Fremont tried the railroad industry. His reputation damaged by an 1873 conviction for his role in a swindle, he nevertheless resumed his political career, and later in the decade began serving as territorial governor of Arizona but depended on his wife’s income from writing during most of his later years. He died in New York City, July 13, 1890.