About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

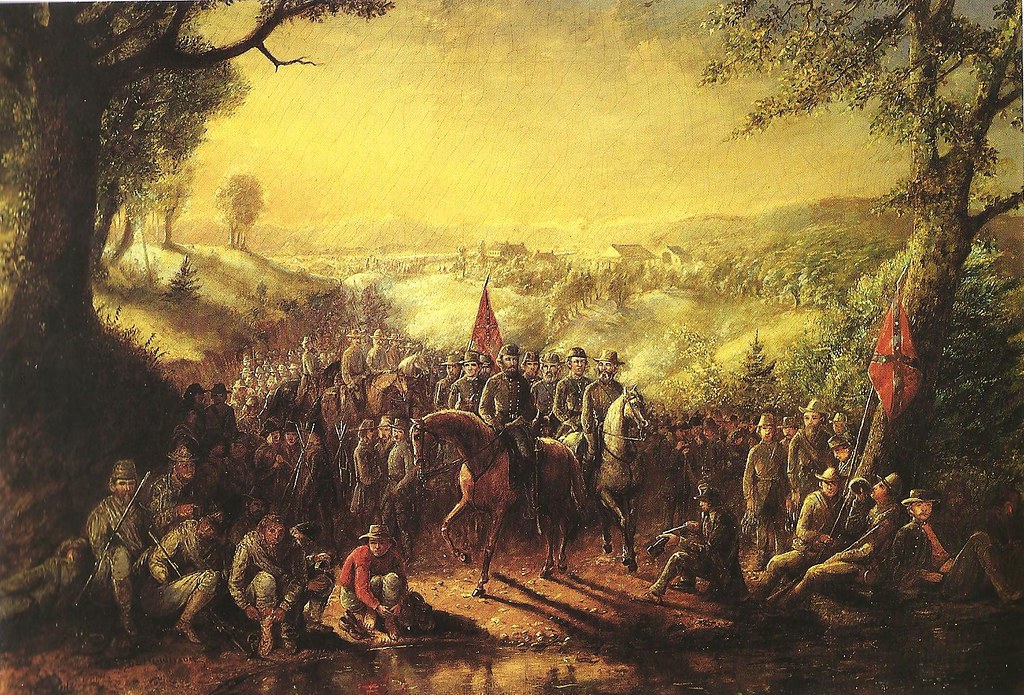

The man who earned the nickname “Stonewall” at Bull Run lived up to his new moniker, and then some, with a campaign of diversion and obstruction in the Shenandoah Valley that quite possibly saved Richmond from falling in the spring of 1862. Using speed and the lay of the land to maximum advantage, General Thomas Jackson foiled the attempts of three Union commands to destroy his small army, whose furious marching earned them a nickname of their own: “Jackson’s foot cavalry.”

As part of the Federal’s Peninsula Campaign, Major General Nathaniel P. Banks was charged with expelling Jackson from the valley, clearing the way for Irvin McDowell and George McClellan to converge on Richmond. Jackson’s orders from Joseph E. Johnston were simply to keep Banks busy. But Jackson, emboldened by bad intelligence, led 3,400 men into Kernstown in March against what turn out to be a 9,000-man infantry division commanded by Brigadier General James Shields, and were routed. The cloud of defeat, though, contained a silver living: Lincoln, feeling threatened by Jackson’s persistence, decided to keep Banks in the valley and McDowell’s Corps near Fredericksburg, depriving McClellan of more than 30,000 troops.

"It was said by some of the boys who timed us that we once marched three miles in thirty-three minutes" -- One of Jackson's infantryman

“If the enemy can succeed so readily in disconcerting all our plans by alarming us first at one point, then at another,” said McDowell after his march was halted, “he will paralyze a large force with a very small one.” Jackson’s strategy was a brilliant study in just that: “Always mystify, mislead and surprise the enemy. Never fight against heavy odds if… you can hurl your own force on only a part. A small army may thus destroy a large one.”

Jackson embarked on his Valley Campaign with 17,000 men, half the enemy’s strength. In May, Jackson faked a move to Richmond by marching his army across the Blue Ridge, then trained back and won the Battle of McDowell on May 8. Banks’s division expected the next attack at Strasburg. Instead, Turner Ashby’s cavalry feinted attacks at Strasburg while Jackson marched across Massanutten Mountain into the Lurary valley and routed a small Union force at Front Royal on May 23. Suddently Jackson was ten miles east of Banks’s flank with a two-to-one man advantage.

Ashby was one of two men instrumental in helping Jackson outmaneuver the Federals. Known as the Black Knight, he was “light, active, skilful, and we are tormented by him like a bull with a gadfly,” wrote one Union soldier. The other was the mapmaker Jedediah Horchkiss, whose detailed surveying of the valley gave Jackson a tremendous advantage over his opponents in navigating the tricky terrain. The Hotchkiss map Jackson carried was eight and a half feet long.

The Foot Cavalary Strikes

FROM FRONT ROYAL., JACKSON’S ARMY MARCHED NORTH AND won the Battle of Winchester on May 25, forcing Banks across the Potomac and taking so many supplies off him that the Rebels took to calling him “Commissary Banks.” Lincoln ordered McDowell and Fremont, now in command west of the Blue Ridge, to converge on Stasburg, cutting off Jackson’s escape route back through the valley. For all practical purposes, the coordinated attack on Richmond was scotched.

Though both Fremont’s and McDowell’s foced (under Shields’s command) were closer to Strasburg,Jackson beat them there along the Valley Pike, slipping through on June 1. The speed with which his men marched through the valley and then back again — 646 miles in 48 days all told — is what earned them comparison to cavalrymen. But this glory came at a high price. “He druv us like Hell,” said one veteran. An officer said that Jackson considered “all who were weak and weary, who fainted by the wayside, as men wanting in patriotism.” Another criticized his “utter disregard for human suffering.”

In fact, Jackson was almost without an army for the spring, driving his troops to near mutiny during the winter with an ill-conceived campaign into West Virginia. The same men who would come to call him “Old Jack” during the Valley Campaign had earlier called him “Old Tom Fool.” Jackson’s famous eccentricities — his aversion to pepper and his habit of sucking lemons on the battlefield — certainly played into this, as well as his religious fervor. “Praying and fgihting appeared to be his idea of the ‘whole duty of man’,” said General Richard Taylor.

After escaping through Stasburg, the chase was on, and the combined forces of Fremont and shields, marching parallel on either side of the Shenandoah River, threatened to overwhelm Jackson’s army. Ashby once again kept the two commands distracted and separated, picking fights and burning bridges until he was killed June 6 near Harrisonurg in a skirmish with the Pennsylvania Bucktails. Jackson made it to Port Republic, setting up defenses near the only intact bridge, with Fremont and Shields stranded on opposite sides of the river from one another.

A token force under Richard S. Ewell fought with Fremont on the Battle of Cross Keys on June 8, keeping him at bay while Jackson concentrated the rest of his force, almost 8,000 men, against 3,000 of Shields’s men at the Battle of Port Republic on June 9. Whipped again, the Union slowly retreated from the valley. Jackson had won five battles against three Union commands totaling 33,000 men, bringing superior numbers to each battle save Cross Keys. In all he diverted 60,000 Union troops from Richmond, and Jackson himself took on an aura of invincibility that would last until his death.