About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

The History of the Life of Rev. Wm. Mack Lee states that its author, William Mack Lee (1835-1932), was a body servant and cook for General Robert E. Lee during the Civil War and until the general’s death in 1870. However, this claim, like many others in W. M. Lee’s brief 1918 autobiography, has been disputed by recent scholarship. Much of Lee’s History has not been confirmed by independent evidence, while several claims that Lee made about his life before and after enslavement are contradicted by historical documents.

According to W. M. Lee’s story, he was raised at the General’s Arlington Heights estate, where he served “Marse Robert, as I called him” even after being legally emancipated in 1865 (p. 3).

W.M. Lee’s History portrays him as having been ordained “a Missionary Baptist preacher” in Washington, D.C., in 1881 and having gone on to found four separate congregations in southern Maryland and northern Virginia. The History also states that in 1887, W.M. Lee organized the State Benevolent Association of Virginia, an organization dedicated to relieving the physical needs of the poor. In 1912, W.M. Lee, according to the History, successfully raised the funds to build a stone and brick church for his fourth and final congregation in Churchland, Virginia.

W.M Lee published his History to help him raise money from white southerners to complete the financing for his Churchland, Virginia, pastorate. No doubt the minister’s claims in his History of having been wounded by a Yankee bullet and having served Robert E. Lee himself during the Civil War got the attention of southern whites whom W.M. Lee solicited for funds.

W.M. Lee’s History (1918) was published in Newport News, Virginia, by the Warwick Printing Co. The narrative alternates between first-person accounts written or dictated by Lee and a third- person narrative written by an unknown author—perhaps a reporter in “the office of the World-News” where Lee solicited donations for his church (p. 7). Lee hoped that his story “might cause some of the young negroes who have school advantages from childhood and early youth, to consider life more seriously and if men of my type had lived in their time, how far they would exceed them along lines of religious, educational and business activities” (p. 6).

Works Consulted: Niven, Steven J., “William Mack Lee,” African American National Biography, Vol. 5, Ed. Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, 204-06; “Media Images,” Virginia Historical Society, 7 Nov. 2008.

Copyright 1918, by Rev. Wm. Mack Lee

STILL LIVING UNDER THE PROTECTION

OF THE SOUTHERN STATES

GENERAL ROBERT E. LEE AND OTHER GENERALS

for whom Rev. William Mack Lee cooked four years

during the Civil War, when he was servant to

General Robert E. Lee–1861-1865

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

LC Subject Headings:

I was born June 12, 1835, Westmoreland County, Va.; 82 years ago. I was raised at Arlington Heights, in the house of General Robert E. Lee, my master. I was cook for Marse Robert, as I called him, during the civil war and his body servant. I was with him at the first battle of Bull Run, second battle of Bull Run, first battle of Manassas, second battle of Manassas and was there at the fire of the last gun for the salute of the surrender on Sunday, April 9, 9 o’clock, A. M., at Appomatox, 1865.

The following is a list of co-generals who fought with Marse Robert in the Confederate Army: Generals Stonewall Jackson, Early, Longstreet, Kirby, Smith, Gordon from Augusta, Ga. Beauregard from Charleston, S. C., Wade Hampton, from Columbia, S. C., Hood, from Alabama, Ewell Harrison from Atlanta, Ga., Bragg, cavalry general from Chattanooga, Tenn., Wm. Mahone of Virginia, Pickett, Forest, of Mississippi, Mosby, of Virginia, Willcox, of Tennessee, Lyons, of Mississippi, Charlimus, of Mississippi, Sydney Johnston, Fitzhugh Lee, nephew of Marse Robert, and Curtis Lee, his son.

The writer of this little book, the body servant of Gen. Robert E. Lee, had the pleasure of feeding all these men at the headquarters in Petersburg, the battles of Decatur, Seven Pines, the Wilderness, on the plank road between Fredericksburg and Orange County Court House, Chancellorsville, The Old Yellow Tavern, in the Wilderness, Five Forks, Cold Harbor, Sharpsburg, Boonesville, Gettysburg, New Market, Mine Run, Cedar Mountain, Civilian, Louisa Court House, Winchester and Shenandoah Valley.

At the close of the struggle, General Lee said to General Grant: “Grant, you didn’t whip me, you just overpowered me, I surrender this day 8,000 men; I do not surrender them to you, I surrender on conditions; it shall not go down in history I surrendered the Northen Confederate Army of Virginia to you. It shall go down in history I surrendered on conditins; you have ten men to my one; my

Page 4

men, too, are barefooted and hungry. If Joseph E. Johnston could have gotten to me three days ago I would have cut my way through and gone back into the mountains of North Carolina and would have given you a happy time.” What these conditions were I do not know, but I know these were Marse Robert’s words on the morning of the surrender: “I surrender to you on conditions.”

At the close of the war I did not know A from B, although I had been preaching two years before the war. I was married six years before the war. My wife died in 1910. I am the father of eight daughters and I have twenty-one grand children and eight great-grand children. My youngest child is 42 years old.

I was raised by one of the greatest men in the world. There was never one born of a woman greater than Gen. Robert E. Lee, according to my judgment. All of his servants were set free ten years before the war, but all remained on the plantation until after the surrender.

The following from the Bedford Bulletin, a paper published in the town of Bedford, Va., which town I am now visiting, situated in the mountains in full view of the famous Peaks of Otter; while soliciting means here to finish my church near Norfolk, I caught inspiration to give the readers of this little book, my friends, and friends and admirers of Marse Robert, a brief history of his body servant and cook, the Rev. William Mack Lee, and will, I hope, cause you to purchase one at the price named on back of same, as I will never be able to write another; I am too old.

“Rev. William Mack Lee, one of the best known colored men in the South, is in town this week making an effort to raise funds to complete the payment on his church near Norfolk. He is a Baptist minister and built the church at a cost of $5,500, of which all has been paid except about $500, and he wants to raise this before he returns home.

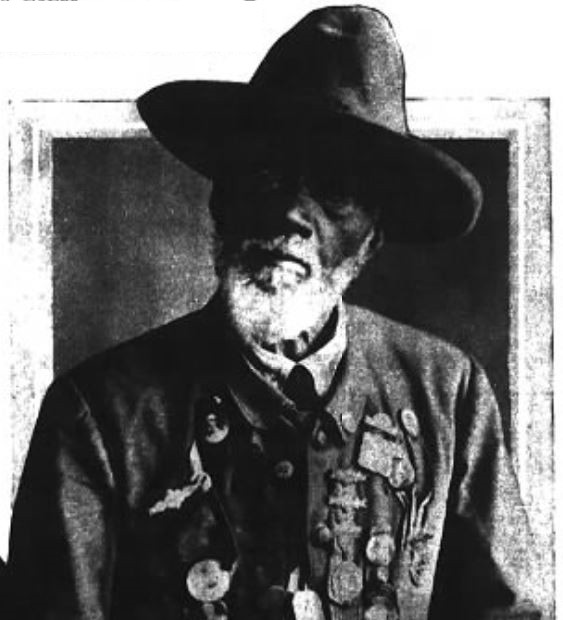

“He was born on the plantation of Gen. Robert E. Lee, in Westmoreland County, 81 years ago, and at the outbreak of the civil war went to the front as the body servant of his distinguished master. He cooked and waited on the Southern chieftian during the entire four years of the war, being with him at the surrender at Appomatox. The fact that the war had set him free was of small moment to him, and he stayed with his old master until his death. He is a negro of the old type, distinguished looking, polite in manner, and, despite his age, is straight, firm of step and

Page 5

bids fair to serve his congregation for many more years. The first day he was in town, he went to the old Burwell homestead, now the home of Mr. John Ballard, because he and his master had stopped there while on a visit to Bedford, soon after the war, and was greatly disappointed to find that the last member of the Burwell family was dead.

“He will be in town all of this week, and if you want to help him pay for his church you will find him on the streets or some one will tell you where he can be found.“

I have been preaching the gospel of Jesus Christ the best I knew, with my limited preparation, for 57 years. My master, at his death, left me $360 to educate myself with. I went to school. I studied hard at the letter, but my greatest learning came from Jesus Christ. God sent me out to preach, and when God sends a man out, he is qualified both with the Holy Ghost and the Spirit. He makes his words sharp as a two-edged sword, and his feet as a burning pillar of brass.

I was ordained in Washington, D.C., July 12, 1881, as a Missionary Baptist preacher. The beginning of my work as an ordained minister was with the Third Baptist Church, Northwest, Washington, D.C., which I built with 20 members, at a cost of $3,000. This church increased from 20 to 500 members during my pastorate. I also built another church in the same city, a frame building, 20 x 36 feet long, at a cost of $2,000. I took this church with 8 members and left it with 200 at the close of two years.

My next pastorate was at Cantorsville, about eight miles northeast of Baltimore, Md., in Baltimore county. There were 12 members of this church, when I took charge. I erected for a house of worship a frame building 22 x 38 at a cost of $3,500. At the end of four years the membership had increased from 12 members to 365. I resigned this charge and took a church in Norfolk county, Virginia, six miles from the city of Norfolk. In this little town called Churchland, I erected a brick building, stone front, for a house of worship, at a cost of $5,500, in the year 1912, all of which has been paid, with the exception of about $500. When I began the building of this last house for God, I sought aid from abroad. I went into three states and by the help of the Lord, and good friends of Virginia, North and South Carolina, I have succeeded in raising over $5,000 for this last project. I preached in 36 counties in South Carolina in 1915, 28 counties in North Carolina, and 23 counties in Virginia. The following is a lst of cities and towns that responded to my call for help in relieving the ndebtedness

Page 6

of my church:–Virginia: Norfolk, Portsmouth, Berkley, Brambleton, Newport News, Hampton, Cape Charles, Eastville, Pocomoke City, Charles City, Suffolk, Lynchburg, Danville, Crewe, Blackstone, Petersburg, Ivor, Waverley, Zuni, Appomattox, Bedford, Roanoke and Hollins. South Carolina: Columbia, Charleston, Summersville, Kingtree, Lake City, Bennettsville, Florence, Mullen, Hartsville, Darlington, Marion, Dillon, Latta, Sumpter, Spartansburg, Orangeville, and Branchville. North Carolina: Raleigh, Wilmington, Rocky Mount, Goldsboro, Greensville, Greensboro, Selma, Clinton, Tarboro, Little Washington, Edenton, Elizabeth City, Wilson, Windsor, Kinston, LaGrange Beaufort, Durham, Hamlet, Rockingham, Gibsonville, Lovington, Ahoskie, Tunis, Reidsville, Winchester.

Having stayed on Marse Robert’s plantation 18 years after the war and with limited schooling, I am not ashamed to give my history to the world that it might cause some of the young negroes who have school advantages from childhood and early youth, to consider life more seriously and if men of my type had lived in their time, how far they would exceed them along lines of religious, educational and business activities. I contribute my success to my teaching from God. When John was writing on the Isle of Patmos, God appeared to him and said, “Write no more, John, seal up what thou hast written.” John fell face foremost. God said, “Rise upon your feet, fear not, I am he who was persecuted, seal up what has been writen and write no more.” The apostle Paul says the letter kills a man, but the word of God makes him alive in our Lord Jesus Christ. A man gets nothing for starting a journey, but gets pay for being faithful and, holding out to the end. If a man lives according to the ten commandmants, he will be blessed, because the chief word in the decalogue, obedience; and obedience to God is service to man.

In addition to my pastoral duties I found time to look after the bodily wants of my fellowman as well as his spiritual needs. To this end I organized the State Benevolent Association of Virginia, for colored people, at Charlottesville in 1887. In 1888 I organized at Washington, D. C., the Supreme Grand Lodge United States Benevolent Association of the District of Columbia. The district associations of Virginia, Maryland, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania are under jurisdiction of the Grand Lodge, whose office and building is located at 428 R Street, N. W., Washington. I am elected Grand Chief for life at a salary of $50 per month and traveling expenses.

Page 7

This association pays sick dues and death benefits and aids its members while out of employment by allowing a weekly sum of $2.00 for 4 weeks each, or until employment is secured, and gives each unfortunate a chance to pay back same to the Association in easy installments of 25 cents a month until the amount has been paid, so advanced by the Association’s Treasurer. The brotherhood requires its members to help those find employment who are not employed.

I have some gavels made out of the poplar where Marse Robert bade farewell to his comrades and instructed them to go home and make themselves good citizens and may I urge those who read this book, especially my people, to take the advice of the humble writer, try to make yourselves good citizens by being industrious, save your money, educate yourselves, buy property, etc., let your religion be more practical and less sentimental. The best friends we have are the Southern people who know all about our raising, and if we colored people want to get along well with the white people, we must show our behavior to, respect and be obedient to them. These are my views to our race.

Your respectable, obedient servant,

REV. WM. MACK LEE.

General Robert E. Lee’s cook and body servant of the Civil War.

Still limping from a yankee bullet, an old darkey, with a grizzled beard and an honest face, hobbled into the office of the World-News at a busy hour yesterday.

“Kin you white folks gimme a little money fur my church?” he asked, doffing his tattered as he bowed.

Typewriters tickled their hurried denial.

The aged negro cocked his head on one side. “What, I ain’t gwine ter turn away Ole Marse Robert’s nigger is yer? You didn’t know dat I was Gen. Robert Lee’s cook all through de wah, did yer?” Every reporter in the office considered that introduction sufficient, and listened for half an hour to William Mack Lee, who followed General Robert E. Lee as body guard and cook throughout the Civil War. When the negro lifted his bent and broken figure from a chair to take his leave every man in the office reached into his pocket, for a contribution.

Page 8

“The onliest time that Marse Robert ever scolded me,” said William Mack Lee, “in de whole fo’ years dat I followed him through the wah, was, down in de Wilderness–Seven Pines– near Richmond. I remembah dat day jes lak it was yestiday. Hit was July the third, 1863.

“Whilst we was in Petersburg, Marse Robert had done got him a little black hen from a man and we named the little black hen Nellie. She was a good hen, and laid mighty nar every day. We kep’ her in de ambulants, whar she had her nest.

“On dat day–July the third–we was all so hongry and I didn’t have nuffin in ter cook, dat I was jes’ plumb bumfuzzled. I didn’t know what to do. Marse Robert, he had gone and invited a crowd of ginerals to eat wid him, an’ I had ter git de vittles. Dar was Marse Stonewall Jackson, and Marse A. P. Hill, and Marse D. H. Hill, and Marse Wade Hampton, Gineral Longstreet, and Gineral Pickett and sum others.

“I had done made some flanel cakes, a little tea, and some lemonade, but I ‘lowed as how dat would not be enuff fo’ dem gemm’n. So I had to go out to de ambulants and cotch de little black hen, Nellie.

There was a tear in William Mack Lee’s voice, but in his eye I fancied that I saw the happy light that always dances in the eyes of his race at the thought of a fowl for cooking.

“I jes’ had to go out and cotch little Nellie. I picked her good, and stuffed her with breod stuffin, mixed wid butter. Nellie had been gwine wid us two years, and I hated fer to lose her. We had been gettin’ all our eggs from Nellie.

“Well, sir, when I brung Nellie inter de commissary tent and set her fo’ Marse Robert he turned to me right fo’ all dem gimmin and he says: ‘William, now you have killed Nellie. What are we going to do for eggs?”

“‘I jes’ had ter do it, Marse Robert.’ says I.

‘No, you didn’t William; I’m going to write Miss Mary about you. I’m going to tell her you have killed Nellie.’

“Marse Robert kep’ on scoldin’ me mout dat hen. He never scolded ’bout naything else. He tol’ me I was a fool to kill de her whut lay de golden egg. Hit made Marse Robert awful sad ter think of anything bein’ killed, whedder der ’twas one of his soljers, or his little black hen.”

Page 9

“I have even seed him cry. I never seed him sadder dan dat gloomy mownin’ when he tol’ me ’bout how Gineral Stonewall Jackson had been shot by his own men.

“He muster hurd it befo’ but he never tol’ me til’ nex’ mawnin’.

“‘William,’ he says ter me, ‘William, I have lost my right arm.’

“‘How come yer ter say dat, Marse Robert?’ I axed him. ‘Yo ain’t bin in no battle sence yestiddy, an’ I doan see yo’ arm bleedin’.

“‘I’m bleeding at the heart, William,’ he says, and I slipped out’n de tent, ’cause he looked lak he wanted to be by hisself.

“A little later I cum back an’ he tol’ me dat Gineral Jackson had bin shot by one of his own soljers. The Gineral had tol’ ’em to shoot anybody goin’ or comin’ across de line. And den de Gineral hisself puts on a federal uniform and scouted across de lines. When he comes back, one of his own soljers raised his gun.

“‘Don’t shoot. I’m your general,’ Marse Jackson yelled.

“‘Dey said dat de sentry was hard o’ hearin’. Anyway, he shot his Gineral an’ kilt him.

“‘I’m bleeding at the heart, William,’ Marse Robert kep’ a sayin’.

“On July de twelf, 1863, I was shot myself,” continued the old darkey, heaving a deep sigh as he withdrew his thoughts from the death of General Stonewall Jackson.

“Yer see dat hole in my head? Dat whar a piece er de shell hit me. Anudder piece struck me nigh de hip.

“I had jes give Marse Robert his breakfas’ an’ went to git old Traveler fer him to ride ter battle. Traveler was Marse Robert’s horse what followed him ’round same as a dog would, and would never step on de dead men, but allers walked betwixt and aroun’ ’em.

“I went out an’ curried and saddled Traveler. I hyeard dem jack battery guns begin to pop an’ bust an’ roah. I saddled Traveler and tuck him in front o’ Marse Robert’s tent.

Page 10

“Jes’ as Marse Robert cum out’n his tent a shell hit 35 yards away. It busted, and hit me, an’ I fell over.

“I must o’ yelled, ’cause Marse Robert said he ain’t never hyeard no noise like de wan I hollered. He cum over and tried to cheer me up, an’ I hollered lak one o’ dem jackass guns.

“Marse Robert lafed so hard ’cause he said he ain’t never seed a nigger holler so loud. An’ den he called for de ambulants an’ dey tuck me ter de hospital.”

William Mack Lee has all the praise in the world for “Marse Robert.” He tells many interesting incidents of the Southern hero’s life in the tent and field.

The old negro is here now trying to raise $418 with which to complete a fund of $5,000, most of which he has already secured, for building a church. He has built four churches and is now working on his fifth.

Among the white churches contributing to his fund are nine Baptist, eight Methodist, and six Episcopalians, in Norfolk, four Baptst in Danville, and churches in Lynchburg, Bedford, Crew, Blackstone and Appomattox.

William Mack Lee was born in Westmoreland County, Va., at the old Stafford House, on the Potomac River, 1835. He is 84 years old. He was raised by General Lee as his personal servant.

“Tell de white folks heah to be good ter me an’ my church,” says William. “Tell ’em not ter turn away Robert’s ole nigger.”