About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

For example, Robert Cartmell was a young farmer and slaveowner who lived in Jackson, Tennessee. In the 1850s, Cartmell complained about his slaves a lot. He found that unless he personally supervised their work, the slaves did not do what he assigned them.

Slaves were always present at Clover Bottom, a racetrack owned by Andrew Jackson. Many of the trainers, stableboys, and riders were black. After the races, they gathered in the nearby woods, barbequed chicken, drank whiskey, and “made the woods ring with noise,” Thomas said.

Family relationships and friendships were very important. In some cases, slaves and free blacks together were able to build their own institutions like churches and informal schools.

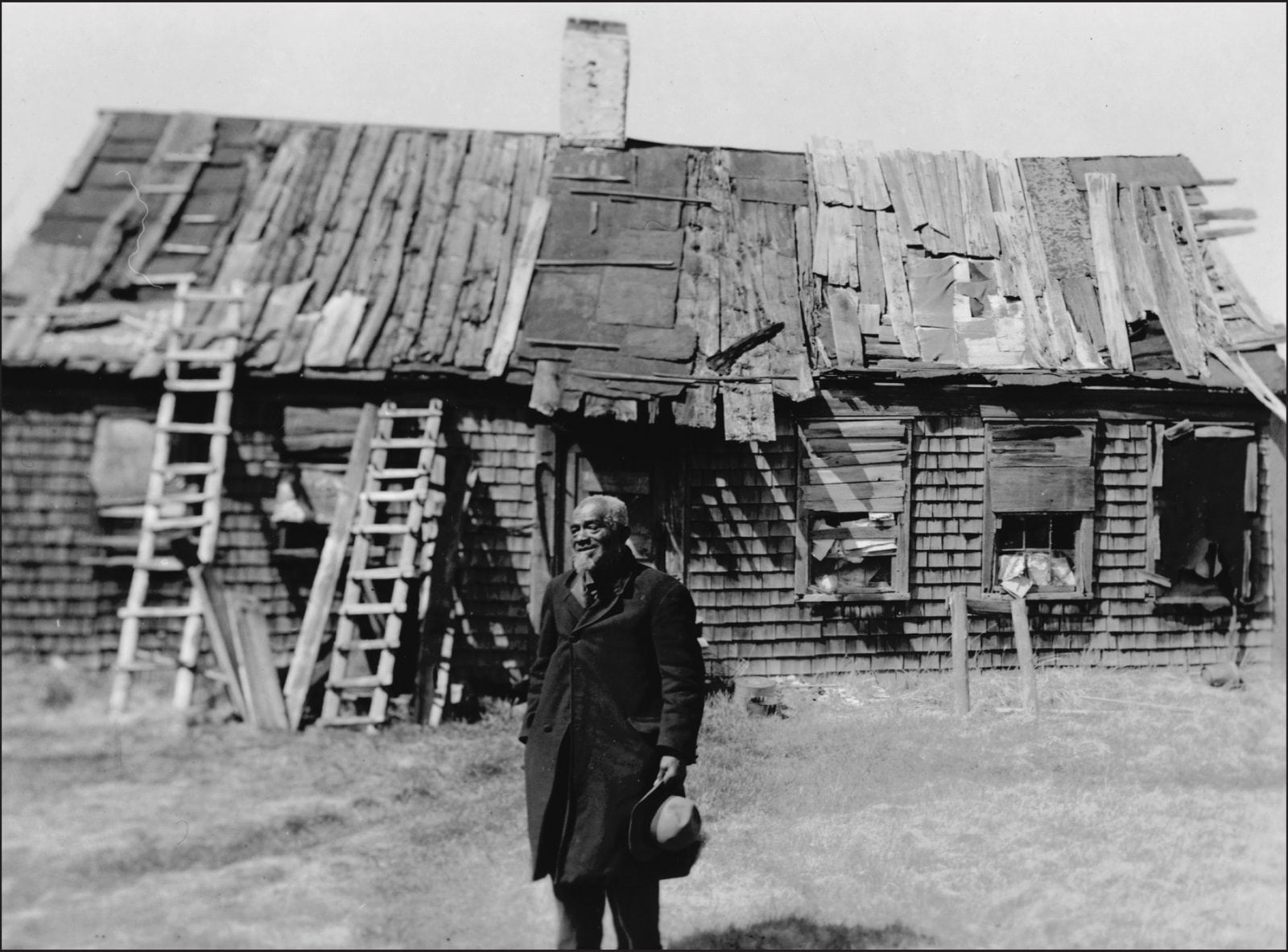

.. who worked on his farm at the Hermitage and at his plantations in other states. At one time he owned more than 150 people.

Jackson generally wanted his slaves to be treated well. He told one overseer “that he was to treat them with great humanity, feed and cloath them well, and work them in moderation.” But Jackson could occasionally be cruel, ordering a slave whipped for running away or being impudent .

The document shown on this page relates to one of the more significant events in Jackson’s life. When an overseer killed one of Jackson’s slaves, Jackson wanted the overseer tried for murder and went to extraordinary efforts to have the event investigated.

Gilbert was a slave on Jackson’s Big Springs plantation in Alabama, “who caused Jackson considerable trouble.” He ran away in 1822 and was captured, so Jackson had him moved to his home, the Hermitage. Gilbert unsuccessfully ran away from there in 1824 and 1827, re-captured the last time after being on the run for two months.

The overseer, Ira Walton, wanted to punish Gilbert, but Jackson had forgiven the slave every time. Walton testified later at his trial that this “had made him (Gilbert) much worse and more difficult to be controlled,” adding that “Gilbert was the most insolent slave he owned.”

Jackson finally agreed that Gilbert should be whipped, though “moderately with small rods [sticks].” Walton tied Gilbert up and walked him through the woods to whip him in front of the other slaves. Something happened during that walk that resulted in Gilbert’s death.

Walton claimed that Gilbert slipped out of the ties and attacked him. In the fight that ensued, Gilbert was stabbed and collapsed. Jackson summoned a doctor, but Gilbert died from his wounds.

Jackson then sent this note to the coroner. The note says:

“An unfortunate occurrence has taken place today on my farm, between my overseer, & one of my negro men, which terminated in the death of the latter. Notwithstanding I believe the fatal stab was given in Self Defense, still as I wish justice to be done, I request a coroner inquest over him.”

A seven member jury was quickly assembled, several of whom were Jackson’s relatives by marriage. The jury heard from Walton, and saw the bruises on his body. A slave boy who witnessed the fight also said Gilbert attacked Walton. The jury decided not to indict Walton because it was self-defense.

Despite the ruling of the jury, Jackson fired Walton. Jackson then got in touch with Andrew Hays, the state prosecutor. Jackson said he considered himself “the guardian of my slave, [and] it is my duty to prosecute the case so far as justice to him [the slave] may require it.”

Jackson later signed a bill to indict Walton for murder, but a grand jury returned a verdict of ‘Not a True Bill,’ which meant that Walton was released from further prosecution.

While Jackson never said so, apparently he was greatly upset by Gilbert’s death. He went beyond what would have been considered the norm for the times in trying to get Walton tried for murder. One historian concludes that for whatever reason, Jackson “was genuinely troubled by Gilbert’s death.”

Today we can only guess at what the factors affecting Jackson’s attitude may have been.