About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

While conditions were notoriously cold and harsh and provisions were in short supply, it was at the winter camp where George Washington proved his mettle and, with the help of former Prussian military officer Friedrich Wilhelm Baron von Steuben, transformed a battered Continental Army into a unified, world-class fighting force capable of beating the British.

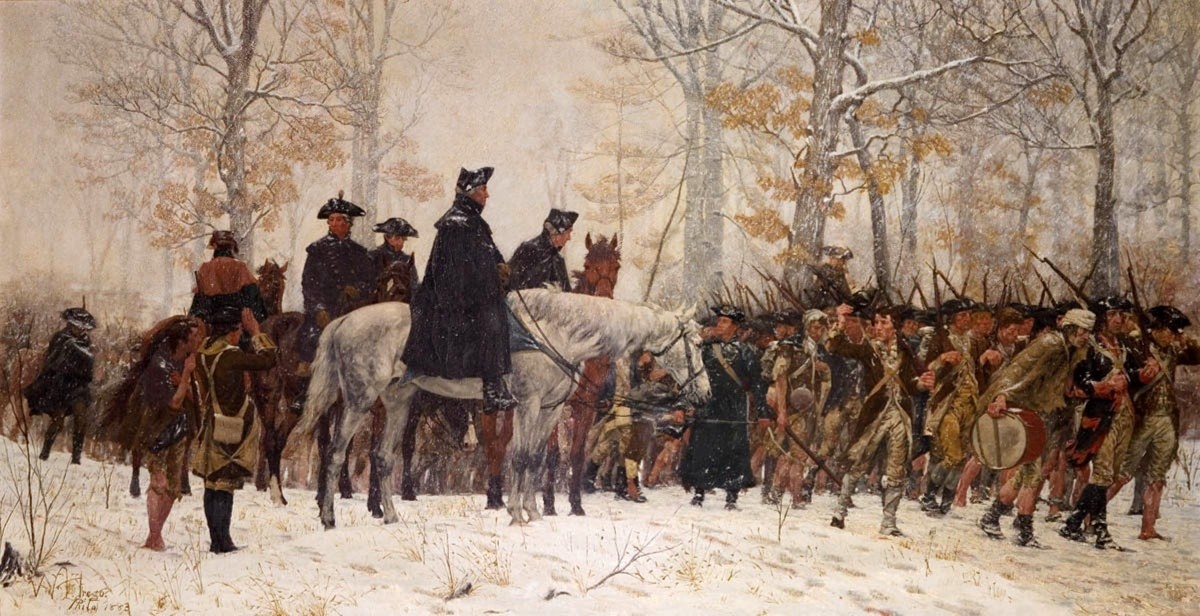

General George Washington and his weary troops arrived at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania six days before Christmas in 1777. The men were hungry and tired after a string of losing battles that had resulted in the British capture of the patriot capital, Philadelphia, earlier in the fall. The defeats had led some members of the Continental Congress to want to replace Washington, believing he was incompetent.

The Valley Forge winter camp site was approximately 20 miles northwest of Philadelphia—about a day’s march from the British-occupied American capital. Most of the land had previously been cleared for agriculture, leaving an open, rolling landscape.

Washington picked the spot because it was close enough to keep an eye on British troops sheltering in Philadelphia, yet far enough away to prevent a surprise attack on his own Continental Army. Washington and his men would remain at the camp for approximately six months, from December 1777 until June 1778.

Within days of arriving at Valley Forge, troops constructed 1,500 to 2,000 log huts in parallel lines that would house 12,000 soldiers and 400 women and children throughout the winter. Washington directed that each hut measure approximately 14 feet by 16 feet. Sometimes the soldiers’ families joined them in the space as well. Soldiers were instructed to search the countryside for straw to use as bedding, since there were not enough blankets for everyone.

In addition to the huts, the men built miles of trenches, military roads and paths. According to the National Park Service, one officer said the camp “had the appearance of a little city” when viewed from a distance. General Washington and his closest aides lived in a two-story stone house near Valley Forge Creek.

Popular images of life at Valley Forge depict tremendous suffering from cold and starvation. While it was cold, the National Park Service says there wasn’t anything out of the ordinary about the conditions at Valley Forge, characterizing the hardship as “suffering as usual” since the Continental soldier experienced a perpetual state of hardship.

A lack of organization, food and money shortages plagued the Continental Army throughout the first half of the seven-year-long revolution. These problems exacerbated the harsh living conditions at Valley Forge, during the third year of the war.

While the winter of 1777-1778 wasn’t exceptionally cold, many soldiers lacked proper clothing, which left them unfit to serve. Some were even shoeless. As Washington described in a December 23, 1777 letter to Henry Laurens, “…we have, by a field return this day made no less than 2,898 Men now in Camp unfit for duty because they are bare foot and otherwise naked…”

Army records suggest that each soldier received a daily ration of one-half pound of beef during January 1778, but food shortages during February left the men without meat for several days at a time.

Cold and starvation at Valley Forge were not even the most dangerous threats: diseases proved to be the biggest killer. As the National Park Service says, “Disease was the true scourge of the camp.” By the end of the six-month encampment, some 2,000 men—roughly one in six—died of disease. Camp records indicate that two-thirds of the deaths happened during the warmer months of March, April and May when soldiers were less confined to their cabins and food and other supplies were more abundant.

The most common illnesses included influenza, typhus, typhoid fever and dysentery—conditions most likely exacerbated by poor hygiene and sanitation at the camp.

Despite the harsh conditions, Valley Forge is sometimes called the birthplace of the American army because, by June of 1778, the weary troops emerged with a rejuvenated spirit and confidence as a well-trained fighting force.

Much of the credit goes to former Prussian military officer Friedrich Wilhelm Baron von Steuben. At the time, the Prussian Army was widely regarded as one of the best in Europe, and von Steuben had a sharp military mind.

Von Steuben arrived in Valley Forge on February 23, 1778. General George Washington, impressed by his acumen, soon appointed von Steuben temporary inspector general. In his role, von Steuben set standards for camp layout, sanitation and conduct. For instance, he demanded that latrines be placed, facing downhill, on the opposite side of camp as the kitchens.

More importantly, he became the Continental Army’s chief drillmaster. Von Steuben, who spoke little English, ran the troops through a gamut of intense Prussian-style drills. He taught them to efficiently load, fire and reload weapons, charge with bayonets and march in compact columns of four instead of miles-long single file lines.

Von Steuben helped to prepare a manual called “Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States,” also called the “Blue Book,” which remained the official training manual of the Army for decades.

The British soon tested the Continental Army’s newfound discipline at the Battle of Monmouth, which took place in central New Jersey on June 28, 1778. While many historians consider the Battle of Monmouth a tactical draw, the Continental Army fought for the first time as a cohesive unit, showing a new level of confidence, according to the American Battlefield Trust. The Americans used artillery to hold off British troops and even launched bayonet counterattacks—skills they had sharpened while drilling under von Steuben at Valley Forge.

“In the old days,” writes archivist and author John Buchanan, “the Continentals probably would have fled.” But, as Wayne Bodle writes in The Valley Forge Winter: Civilians and Soldiers in War, after their six months of training in the mud and snow of Valley Forge, Washington’s troops became imbued with “a deeper identification with and pride in their craft.”

Following British victories at the Battle of Brandywine (September 11, 1777) and the Battle of the Clouds (September 16), on September 18 General Wilhelm von Knyphausen led British soldiers on a raid of Valley Forge, burning down several buildings and stealing supplies despite the best efforts of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Hamilton and Captain Henry Lee to defend them. The engagement became known as the “Battle of Valley Forge.” The Continental Army left Valley Forge for good in June 1778.