About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Born on January 8, 1831, in Knoxville, in Crawford County, Pemberton grew up and attended the local schools in Rome, where his family lived for almost thirty years.

He studied medicine and pharmacy at the Reform Medical College of Georgia in Macon, and in 1850, at the age of nineteen, he was licensed to practice on Thomsonian or botanic principles (such practitioners relied heavily on herbal remedies and on purifying the body of toxins, and they were viewed with suspicion by the general public).

He practiced medicine and surgery first in Rome and its environs and then in Columbus, where in 1855 he established a wholesale-retail drug business specializing in materia medica (substances used in the composition of medical remedies). Some time before the Civil War (1861-65), he acquired a graduate degree in pharmacy, but the exact date and place are unknown.

Pemberton’s business opened its doors in 1860 and had $35,000 worth of the latest most high-tech equipment on its side. Some of it was even designed and patented by the company itself, which one reporter from the Atlanta Constitution called “a magnificent establishment” in 1869.

When the labs were relocated to Atlanta, he dubbed Pemberton’s business “one of the most splendid Chemical Laboratories that there is in the country.” And though he was also called “the most noted physician Atlanta ever had,” accolades and respect did not prevent him from joining the fray of war when the time came.

Pemberton joined the army of the Confederacy in May 1862, and was made first lieutenant. As a founding member of the Third Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Pemberton defended the city of Columbus became lieutenant colonel as a result.

When Union troops under General James Wilson’s command reached Columbus one Easter Sunday of 1865, Pemberton was in direct line of fire and almost died. The battle would directly impact the rest of his life and ultimately lead to both his greatest success and biggest weakness due to his subsequent addiction to morphine.

Had Pemberton not been injured by both gunshot and sword wounds, he likely would’ve never resorted to morphine in the first place. That would’ve arguably prevented him from inventing Coca-Cola, but also liberated him from the future troubles of having a substance abuse problem.

The wounded soldier became hooked almost immediately, using it initially to relieve his pain. Unfortunately, he ultimately fell victim to the chemical as a lifelong crutch for whatever mental maladies and psychological ailments he was suffering from.

When the smoke of the Civil War cleared and America busied itself with the duty of getting back to living, Pemberton partnered with Columbus physician Austin Walker and expanded his lab. The idea was to develop new products and sell medical and photography supplies, and branch out into cosmetics.

The Sweet Southern Bouquet perfume was a success, and in 1869, the veteran formed the Pemberton, Wilson, Taylor and Company firm and moved to Atlanta the following year. As a trustee of Atlanta Medical College (which is now the modern-day Emory University Medical School), he solidified the reputation of himself and of his labs as sophisticated and state-of-the-art.

The original beverage was called Pemberton’s French Wine Coca and hit the market in 1885. With coca leaves imported from South America adding a particular twist what would otherwise be a mere soft drink, Pemberton sold the soda as a nerve tonic, mental aid, headache remedy — and a cure for morphine addiction.

The seemingly all-curing jack of all trades drink sold rather well, with Pemberton later admitting to an Atlanta newspaper reporter that he based it on an Italian-French beverage called Vin Mariani which was previously endorsed by Pope Leo XIII. That one, too, contained stimulating coca leaves.

Pemberton differentiated his particular drink by adding extracts from other tropical plants, like the caffeine-containing kola nut from African trees and the Central American damiana shrub leaf — which was rumored to contain aphrodisiac properties.

When hushed whispers of alcohol prohibition began to hit Atlanta’s city government in 1886, Pemberton feared his new and popular drink could soon be banned. Though this change in laws was actually enacted that very year, prohibition in the city only lasted for one year.

Nonetheless, the now renowned shift from Pemberton’s French Wine Coca to Coca-Cola had already taken root.

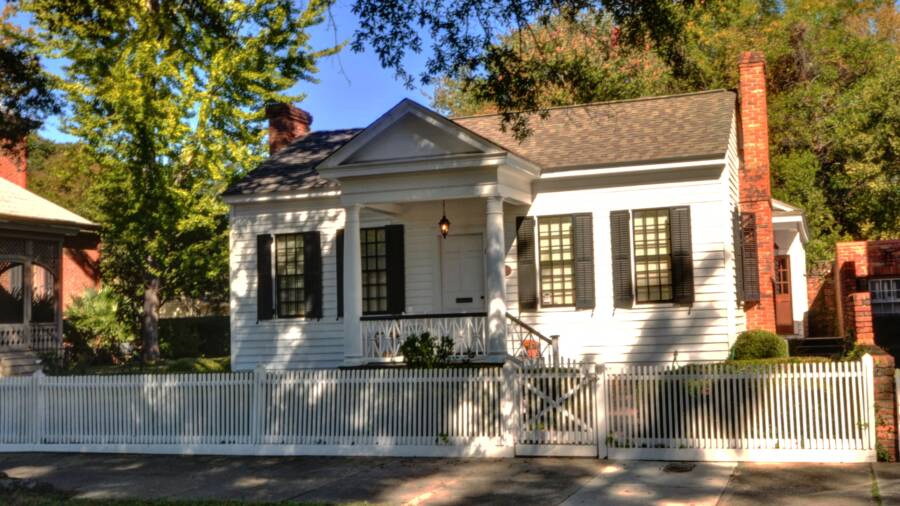

At his Marietta Street home, the pharmacist-turned-war-veteran began a series of experiments on the drink using an industrial-sized mixing-and-filter machine that ran from the building’s second story down to the ground level.

Pemberton sent out samples of his new alcohol-free iteration to pharmacies around Atlanta. His nephews were in charge of recording and collating customer reactions, which led to one of Pemberton’s main breakthroughs in arriving at the final concoction — adding citric acid to combat the syrup’s intense sweetness.

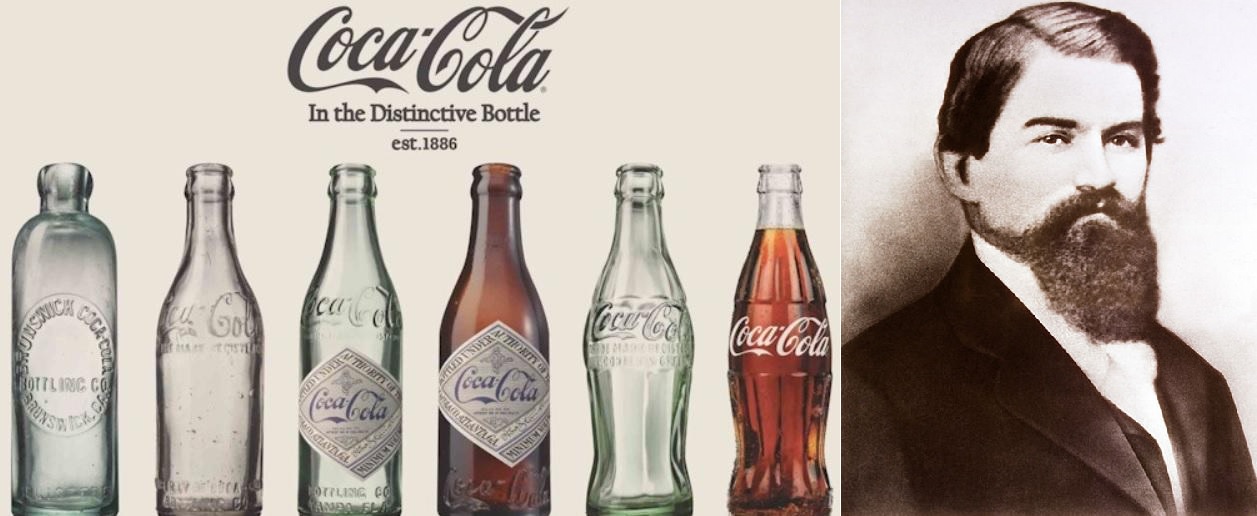

The final version was finished in May 1886 and was initially sold only in syrup form at the Jacob Pharmacy in town. Sold for five cents per portion, it would be mixed on the spot with water before customers drank it. Only eight years later did Pemberton decide to bottle the beverage, cut out the middle man, and expand. He formed Pemberton chemical Company to market it and put his son in charge of production. Charles Pemberton eventually succumbed to his own morphine addiction and died.

As for the name — Coca-Cola — it was Pemberton’s bookkeeper Frank Robinson who coined the billion-dollar moniker. He even designed the logo, which is still in use today, more than a century later.