About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

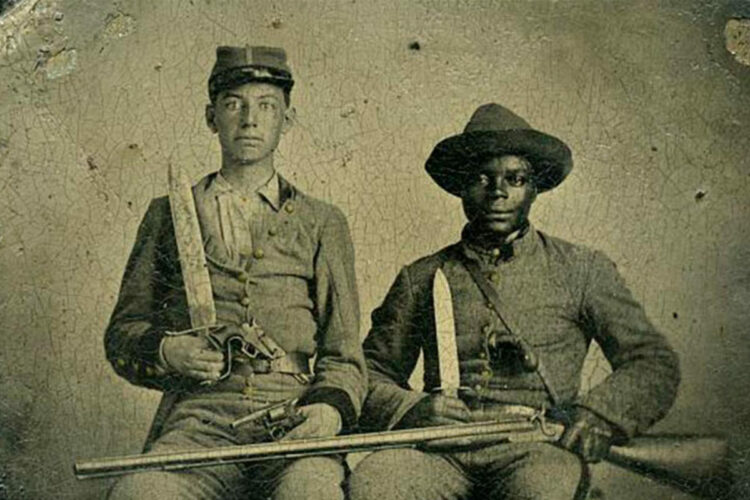

As a topical subject for many years has stemmed the topic of black soldiers whom fought for the Confederacy, whereas each individual historian typically differs on conclusions, especially when it’s relating to their ancestry.

The article published below is an outlook of archival research, originally published in 2012. As these form of pieces are opinion related, it’s up to the individual to determine if you deem such information vital, accurate, or dismissive.

The National Archives and Records Administration has a substantial, though scattered, set of records for “Black Confederates.” Thousands of body servants, laborers, cooks, musicians, teamsters, etc., encamped with and served the Confederate Army. But if one is looking for African Americans who were regularly enlisted to serve under arms, both the subject and the sources are problematic. To my knowledge, no NARA records have come to light that document the service of African-American soldiers fighting for the South to any significant degree.

The notion that black troops fought to defend a nation founded primarily to preserve slavery is not as absurd as some might believe, however. Records show that the Confederate War Department received—and declined—offers of “colored companies” in 1861.

Researching Black Confederates involves looking at many different records, so precise definition and status are important. For example, the NARA has a muster roll of the field, staff and band of the 1st South Carolina Infantry for January 1– February 28, 1862. Beside the musicians’ names is a comment: “The Band is composed entirely of Negroes—free men of color— They are borne upon the muster rolls of several of the Companies of the Regiment.” The NARA’s Compiled Military Service Records (CSRs) include files for each of these men. They served in the army, but they had separate status from regularly enlisted soldiers, confirmed by Confederate Army regulations. No rolls are known to have survived for the few African-American companies raised in Richmond in March 1865, when the Confederate Congress belatedly authorized such enlistments.

NARA’s Confederate Service records show that the 1st Regiment Native Guards, Louisiana Militia, was made up of free men of color. But that militia unit was not considered part of the Confederate Army and did not see battle.

Despite widespread claims that modern historians have conspired to conceal knowledge of black Confederates, the late archivist Arthur W. Bergeron Jr. noted there is substantial literature on the subject, dating as far back at least as a chapter in Joseph T. Wilson’s The Black Phalanx (1887), and extending through accounts such as Bell Irvin Wiley’s Southern Negroes, 1861- 1865 (1938) and James H. Brewer’s The Confederate Negro: Virginia’s Craftsmen and Military Laborers, 1861-65 (1969), to Bruce Levine’s Confederate Emancipation: Southern Plans to Free and Arm Slaves During the Civil War (2007). These scholarly studies, however—some of which have made use of NARA records—have had little impact on public perception of the issue.

A small number of individuals of African descent who were apparently able to pass as whites do seem to have served as Confederate soldiers. The number of African Americans who served seems to be roughly on par with the number of black soldiers who were found out, ejected from the Army and then put to work as laborers. In addition, in The Confederate Negro, James Brewer quotes a Confederate report stating that late in the conflict a group of Richmond hospital attendants were temporarily armed and positioned in the trenches.

It has been pointed out that Confederate records are incomplete, so evidence for blacks in Southern service could have been lost. In fact, although there are gaps, the records are so extensive—especially when supplemented by the “Miscellaneous Unfiled Slips and Papers Belonging in Confederate Compiled Service Records”—as to preclude such a possibility. Records for Confederate soldiers do not generally indicate race, but often those records do provide some form of physical description that would indicate the soldier’s complexion.

Most of the NARA’s holdings on African Americans in the Confederacy can be found in a series of Slave Rolls that is part of Record Group 109, the “War Department Collection of Confederate Records.” These are monthly reports indicating the date and place of the report, the slaves’ names, amounts paid to their owners and the name of the man in charge.

One NARA source does suggest that a few blacks supported the Confederate government: A very small percentage of case files among the records of the postwar Southern Claims Commission are for “colored” applicants whose claims were rejected because witnesses testified to their allegiance to the secessionist cause.

In contrast, a formidable mountain of documentation exists to indicate that most Southern blacks preferred the Union cause. Record Group 393, “Records of U.S. Army Continental Commands,” bulges with documentation on thousands of slaves who deserted their masters when Federals approached. As Southern historian C. Vann Woodward wrote in his 1964 foreword to a new edition of Bell Wiley’s 1938 study: “The evidence destroys the legend of the Negro’s indifference to freedom.”