About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

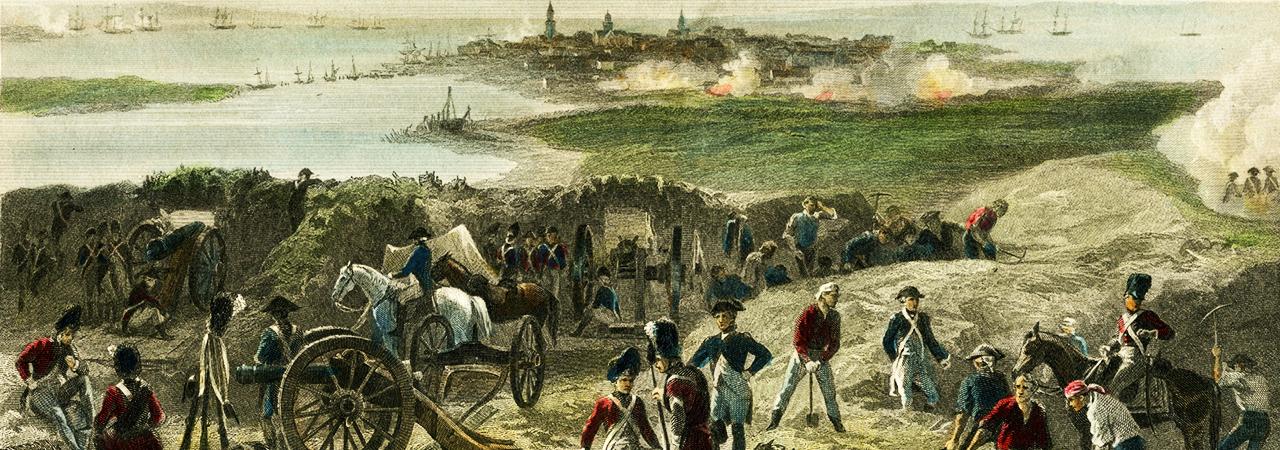

In 1778, the British Commander-in-Chief in America Lt. General Henry Clinton turned his attention to the South, where partisan fighting between Patriot militia and Tories had been heavy. Clinton had been there once before on June 28, 1776 when Colonel William Moultrie had defeated Clinton and Commodore Sir Peter Parker at the Battle of Fort Sullivan. The British had tried to approach Charleston by water and had failed to reach the city proper.

General Clinton and the British government back in London believed that if the British controlled the South, Tories would flock to support the British and Clinton would be able to overwhelm General George Washington in Virginia. During the winter of 1778-1779, the British took control of Georgia including the cities of Savannah and Augusta. They soon began planning the capture of the important port city of Charleston, South Carolina.

In response to the loss of Georgia in December 1778, the Continental Congress replaced native North Carolinian Maj. General Robert Howe with Bostonian Maj. General Benjamin Lincoln as Southern Department Commander. Lincoln had proven to be an able motivator of militia. But that was New England militia, he would not have nearly as much success with Carolina militia. Lincoln’s first task was to retake Georgia.

On May 11, 1779, General Lincoln was able to reoccupy Augusta, Georgia. In September, he was joined by French Admiral d’Estaing in laying siege to Savannah. The British held out for a month. In October, D’Estaing abandoned the siege and sailed south to the West Indies for the winter. Without naval support, Lincoln was forced to give up the siege and return to Charleston, South Carolina.

In December 1779, General Clinton sailed himself sailed south bound for Charleston from New York City. The British fleet included ninety troopships and fourteen warships with more than 8,500 soldiers and 5,000 sailors. Because they had been delayed several months in leaving, the fleet now sailed through stormy seas. The first storm hit on December 27 and lasted three days. On January 1, 1780 another storm hit and lasted six days. This pattern continued and the fleet was separated. From March 11 until the 21th the British fortified their position which was located where the Wappoo Creek flowed into the Ashley River. They mounted artillery to shell American ships and keep the Ashley River secure. They then moved upstream and north, away from Charleston, slowly securing the plantations along the way while the Americans shadowed them from across the river.

Under the cover of fog on March 29th, the British crossed the Ashley River upstream from the heavily fortified Ashley Ferry and established themselves on Charleston Neck. When the Americans learned that the British were on the Neck, they abandoned their breastworks at Ashley Ferry. By April 1st, the British had moved down into position to begin their siege works.

Meanwhile, naval maneuvering in Charleston Harbor for the Americans was a disaster. In December 1779, four frigates had arrived on orders from Congress under the command of Commodore Abraham Whipple, which were joined by four ships from South Carolina and two French ships. There were 260 guns afloat and forty guns at Fort Moultrie. Before the British ever arrived, Whipple informed Maj. General Benjamin Lincoln that the flotilla could not defend the bar that blocked the entrance to Charleston Harbor.

General Lincoln questioned Commodore Whipple’s conclusion, but Whipple was backed up by a naval board. Whipple chose to first withdraw to the mouth of the Cooper River. Meanwhile the British began their approach on March 20th. When Whipple saw the size of the British attack fleet, he scuttled the ships at the entrance of the river. On April 8th, the British fleet moved in with fire only from Fort Moultrie.

On April 12th, Lt. General Henry Clinton ordered Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton and Major Patrick Ferguson to capture Monck’s Corner. It was a crossroads just south of Biggins Bridge near the Santee River. Five hundred rebels under General Isaac Huger were stationed there with orders from General Lincoln to hold the crossroads so that communications with Charleston would remain open.

On the evening of April 13, 1780, Lt. Colonel Tarleton gave orders for a silent march. Later that night, they intercepted a messenger with a letter from Huger to Lincoln and thus learned how the rebels were deployed. At three o’clock in the morning on the 14th, the British reached the American post, catching them completely by surprise and quickly routing them. Following the skirmish, the British fanned out across the countryside and effectively cut off Charleston from outside support.

On April 2nd, siege works were begun about 800 yards from the American fortifications. During the first few days of the siege, the British operations were under heavy artillery fire. On April 4th, they built redoubts near the Ashley and Cooper Rivers to protect their flanks. On April 6th, a warship was hauled overland from the Ashley River to the Cooper River to harass crossings by the besieged to the mainland.

At this point on the 12th, Lt. General Henry Clinton ordered Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton to secure the far bank as described previously in the Background. Governor John Rutledge left the city on the 13th. On the 21st a parlay was made between Lincoln and Clinton, with Lincoln offering to surrender with honor. That is, with colors flying and marching out fully armed, but Clinton was sure of his position and quickly refused the terms. A heavy artillery exchange followed.

On April 23rd, Lt. General Charles Cornwallis crossed the Cooper River and assumed command of the British forces blocking escape by land. Finally on April 24th, the Americans ventured out to harass the siege works. The lone American casualty was Tom Moultrie, brother of William Moultrie. On April 29th, the British advanced on the left end of the canal that fronted the city’s fortifications with the purpose of destroying the dam and draining the canal.

The Americans knew the importance of that canal to the city’s defenses and responded with steady and fierce artillery and small arms fire. By the following night, the British had succeeded in draining some water. By May 4th, several casualties had been sustained and the fire had been so heavy that work was often suspended. On the 5th, the Americans made a countermove from their side, but by the 6th, almost all of the water had drained out of the heavily damaged dam and plans for an assault began.

On that same day, May 6th, Fort Moultrie surrendered. On May 8th, General Clinton called for unconditional surrender from Maj. General Benjamin Lincoln, but Lincoln again tried to negotiate for honors of war. On May 11th, the British fired red-hot shot that burned several homes before Lincoln finally called for parlay and to negotiate terms for surrender. The final terms dictated that the entire Continental force captured were prisoners of war. On May 12th, the actual surrender took place with General Lincoln leading a ragged bunch of soldiers out of the city.

The senior officers including Maj. General Benjamin Lincoln eventually were exchanged for British officers in American hands. For all others in the Continental army, a long stay on prison boats in Charleston Harbor was the result, where sickness and disease would ravage them. The defeat left no Continental Army in the South and the country wide open for British taking. Even before Lincoln surrendered, the Continental Congress had already appointed Maj. General Horatio Gates to replace him.

The British quickly established outposts in a semicircle from Georgetown to Augusta, Georgia, with positions at Camden, Ninety-Six, Cheraw, Rocky Mount and Hanging Rock in between. Parole was offered to back country rebels and many accepted, including Andrew Pickens. Soon after securing Charleston, Lt. General Henry Clinton gave command of the Southern Theatre to Lt. General Charles Cornwallis and on June 5th, he sailed north back to New York.

General Clinton’s one order to General Cornwallis before he left, was to maintain possession of Charleston above all else. Cornwallis was not to move into North Carolina if it jeopardized this holding. Clinton also had ordered that all militia and civilians be released from their parole. But in addition, they must take an oath to the Crown and be at ready to serve when called upon by His Majesty’s government. This addition angered many of the locals and led to many deserting or ignoring the order and terms of their parole.

This was a severe blow to the colonies. It was the greatest loss of manpower and equipment of the war for the Americans and gave the British nearly complete control of the Southern colonies.

*courtesy of the Patriot Resource