About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Seven years of British determination to bring South Carolina to her knees met failure. The spirit that had long resisted royal edict and church canon, the fierce desire and indomitable will to be masters of their own destinies, and the dauntless courage that had carved a new way of life from a wilderness were again threatened by oppression; so, little difference was felt among nationalities and creeds, causing a unity to grow among the new world “peasants and shepherds” that shook the foundations of old regimes.

By midsummer, 1781, the Continentals under General Nathaniel Greene had gained virtual control of South Carolina. The retreating British. disillusioned and sick with summer heat, united forces under Colonel Stewart at Orangeburg and began their march to Charleston. Early in September the 2,300 well-equipped British camped in cool shade beside the gushing springs of Eutaw, little dreaming the Continentals were close upon their heels. General Greene, hearing of Washington’s plan to encircle and embarrass the British at Yorktown, determined to prevent Southern aid from reaching the beleaguered Cornwallis. Contingents under Marion, Pickens, Lee, William Washington, Hampton and other South Carolina leaders were called together, and reinforcements from other colonies joined them. These 2,092 poorly-equipped, underfed, and near-naked Americans camped on Sept. 7th. on the River Road at Burdell’s Plantation, only seven miles from Eutaw Springs. Strategy for the ensuing attack is accredited to the genius of the dreaded “Swamp Fox,” General Francis Marion, who knew every foot of the Santee swamps and river.

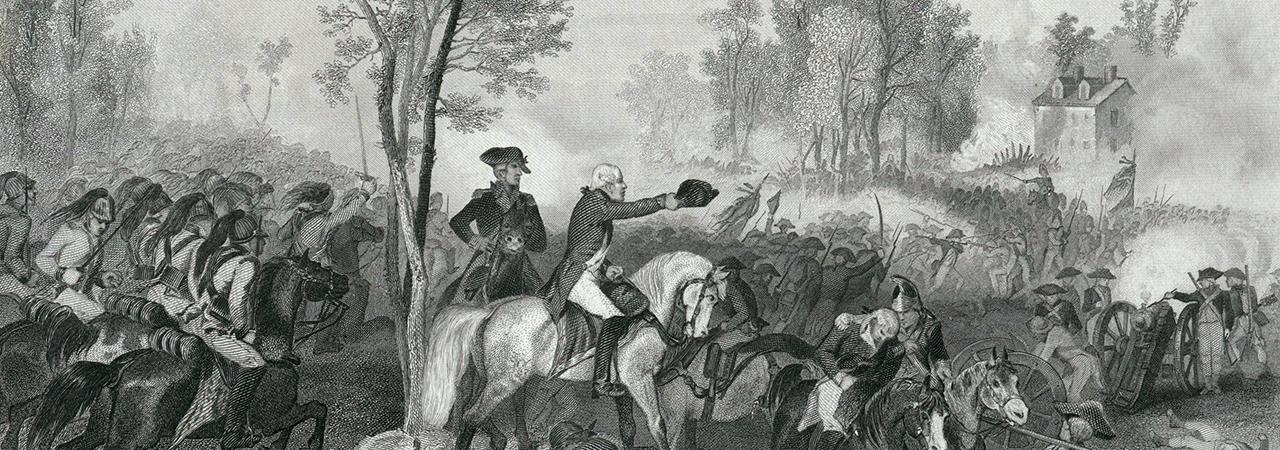

The 8th dawned fair and intensely hot, but the Americans, on short rations and with little rest, advanced in early morning light toward the springs. At their approach the surprised British left their uneaten breakfast and quickly threw lines of battle across the road in a heavily wooded area. Behind them in cleared fields stood a large brick home with a high-walled garden. The woods and waters of Eutaw Creek were on the north. Heavy firing soon crackled and boomed through the shady woods. At first the center of the American line caved in, but while opposing flanks were fighting separate battles, Greene restored the center with Sumner’s North Carolina Continentals. The whole British line then began to give, but Colonel Stewart quickly pulled up his left-flank reserves, forcing the Americans to retreat under thunderous fire. The encouraged British shouted, yelled, and rushed forward in disorder; whereupon Greene (according to J. P. Petit) “brought in his strongest force: the Maryland and Virginia Continentals, Kirkwood’s Delaware’s, and Wm. Washington’s South Carolina cavalry . . . with devastating effect.” The British fled in every direction and the Americans took over their camp. Only Major Majoribanks, on the British right flank and pushed far back into the woods near Eutaw Creek, was able to hold his unit together. Major Sheridan took hasty refuge in the brick home, Colonel Stewart gathered some of his men beyond, and from this vantage they “picked off” many American officers and men.

Greene sent Wm. Washington’s cavalry to deal with Majoribanks, but penetrating the woods with horses was too difficult, so Washington tried to encircle and rout, thus exposing himself to dangerous fire. His horse was shot from under him, he himself was wounded. and his company practically ravaged. When a hand to hand fight developed, a British soldier poised his sword over the wounded Washington, but Majoribanks saw and gallantly turned it aside.

In camp, eating the deserted breakfast, and feeling the battle was won, the hungry, thirsty Americans began plundering the English stores of food, liquors, and equipment. Thoroughly enjoying themselves they ignored their leaders’ warnings and commands. Majoribanks, realizing the disorder, fell upon them. Sheridan and Stewart pounded at their right, and Coffin came in from their left. The stunned Americans fought this impossible situation bravely, but they were put to flight from the British camp.

After more than four hours of indecisive battle under a merciless sun, both armies had had enough. Casualties were extremely high. “Blood ran ankle-deep in places,” and the strewn area of dead and dying was heart-breaking. Greene collected his wounded and returned to Burdell’s Plantation. Stewart remained the night at Eutaw Springs but hastily retreated the next day toward Charleston, leaving behind many of his dead unburied and seventy of his seriously wounded. The gallant Majoribanks, wounded and on his way to Moncks Corner, died in a Negro cabin on Wantoot Plantation. He was buried beside the road, but when lake waters were to cover that area his remains were removed by the S.G.P.S.A. to their present resting place at Eutaw Springs Battlefield.

The claim of several historians that the British won the battle is challenged by Christine Swager in her book The Valiant Died: The Battle of Eutaw Springs September 8, 1781. The book argues that, first, at the end of the battle, the British held the majority, but not the entirety, of the field where the main battle took place. Greene held part of the field where the initial skirmish spilled out of the woods into the clearings. Swager also argues that Greene meant to re-engage the enemy on the following day, but was prevented from doing so because the excssively wet weather conditions negated much of his firepower.

Both armies did not leave the vicinity for at least a full day following the battle. When Greene withdrew, he left a strong picket to oppose a possible British advance, while Stewart withdrew the remnants of his force towards Charleston. His rear was apparently under constant fire at least until rendezvousing with reinforcements near Moncks Corner.

Stewart reported casualties of 85 killed, 351 wounded and possibly as many as 420 missing, a casualty rate of over 40%. Some evidence suggests these numbers were higher. American losses as reported by Greene were 139 dead, 375 wounded, and 41 missing.

Despite winning a tactical military victory the British lost strategically. Their inability to stop Greene’s continuing operations forced them to abandon most of their conquests in the South, leaving them in control of a small number of isolated enclaves at Wilmington, Charleston, and Savannah. The British attempt to pacify the south with Loyalist support had failed even before Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown.

Lord Edward Fitzgerald, later to become famous as a United Irish rebel, served as a British officer at the battle and was badly wounded.

The State Song of South Carolina contains the line “Point to Eutaw’s Battle Bed” in reference to this battle.