About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Sioux, or Dakota, Indians, a large and powerful tribe of Indians, who were found by the French, in 1640, near the headwaters of the Mississippi River. The Algonquiens called them Nadowessioux, whence they came to be called Sioux. They occupied the vast domain extending from the Arkansas River, in the south, to the western tributary of Lake Winnipeg, in the north, and westward to the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains. They have been classed into four grand divisions – namely, the Winnebagoes, who inhabited the country between Lake Michigan as the Mississippi, among the Algonquians; the Assiniboines, or Sioux proper (the most northerly of the nation) ; the Minnetaree group, in Minnesota; and the Southern Sioux, who dwelt in the country between the Arkansas and Platte rivers, and whose hunting-grounds extended to the Rocky Mountains. In 1679 Jean Duluth, a French officer, set up the Gallic standard among them near Lake St. Peter, and next year he rescued from them Father Hennepin, who first explored the upper Mississippi. The French took formal possession of the country in 1685, when they were divided into seven eastern and nine western tribes. In wars with the French and other Indians, they were pushed down the Mississippi, and, driving off the inhabitants of the buffalo plains, took possession.

Others remained on the shores of the St. Peter. Some of them wandered into the plains of Missouri, and there joined the Southern Sioux.

In the War of 1812 the Sioux took sides with the British. In 1822 the population of the two divisions of the tribe was estimated at nearly 13,000. In 1837 they ceded to the United States all their lands east of the Mississippi, and in 1851 they ceded 35,000,000 acres west of the Mississippi for $3,000,000. The neglect of the government to carry out all the provisions of the treaties for these cessions caused much bitter feeling, and a series of hostilities by some of the Sioux ensued; but after being defeated by General Harney, in 1855, a treaty of peace was concluded.

Enraged by the failure of the government to perform its part of the bargain and the frauds practiced upon them, there was a general uprising of the Upper Sioux, in 1862, and nearly 1,000 settlers were killed. The Lower Sioux, of the plains, also became hostile, but all were finally subdued. Fully 1,000 were held captive, and thirty-nine were hanged.

Many bands fled into what was then Dakota Territory, and the strength of

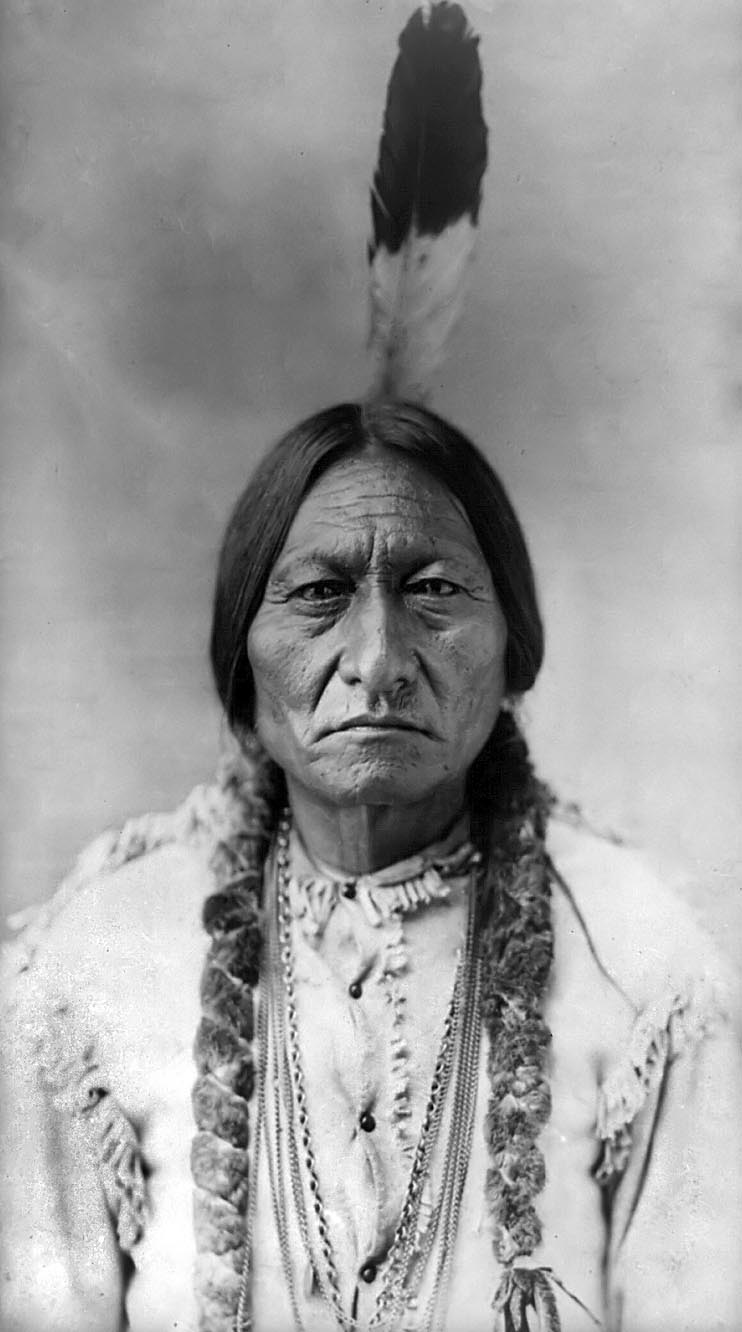

the nation was greatly reduced. The most guilty bands fled into the British dominions, while others, from time to time, attacked settlements and menaced forts. Loosely made treaties were violated on both sides. By one of these the Black Hills were made part of a reservation, but gold having been discovered there, the United States wished to purchase the tract, and induce the Indians to abandon that region and emigrate to the Indian Territory. They showed great reluctance to treat. Sitting Bull, Spotted Tail, and Red Cloud visited the national capital in 1875, but President Grant could not induce them to sign a treaty. Commissioners met an immense number of them at the Red Cloud agency, in September, but nothing was done. The sending of surveyors under a military escort to the Black Hills excited the jealousy of the Sioux, and they prepared for war. In the spring of 1876 a military force was sent against them, and in June a severe battle was fought, in which General Custer and all of his immediate command were slain. This battle will live in infamy, popularly referred to as “The Battle of Little Big Horn”, or “Custer’s Last Stand”. By whatever name it is called, it will be remembered as one of the most significant victories of the Indian Nations. While in the end their cause was lost, they demonstrated their superb bravery and military skill in defeating Custer and humiliating the US Army.

Later, after having been severely beaten in several encounters, the Indians returned, under full pardon, to their reservations.

The advancement made by the Christian or progressive portion of the Sioux Indians in the present South Dakota had long been regarded with disfavor by the pagan and conservative element under the leadership of Sitting Bull, Red Cloud, and Kicking Bear, and the latter eagerly waited for some pretext to bring the question of civilization or non-civilization to a decisive issue. In 1890 there was a failure on the part of the government to meet promptly some of its obligations to the Sioux, especially in the payment of annuities and of moneys due to the Indians for certain lands which they had sold. The crops, too, had failed; Congress had cut down the supplies; and there was naturally a feeling of dissatisfaction among the half famished Indians. Inefficient agents also had been sent out by the government who had little regard for anything save their own personal gain, and not much was done by them to allay the general discontent. All these circumstances combined to favor the designs of Sitting Bull and his associates. A widespread conspiracy was formed, and plans were made for a general uprising in the spring.

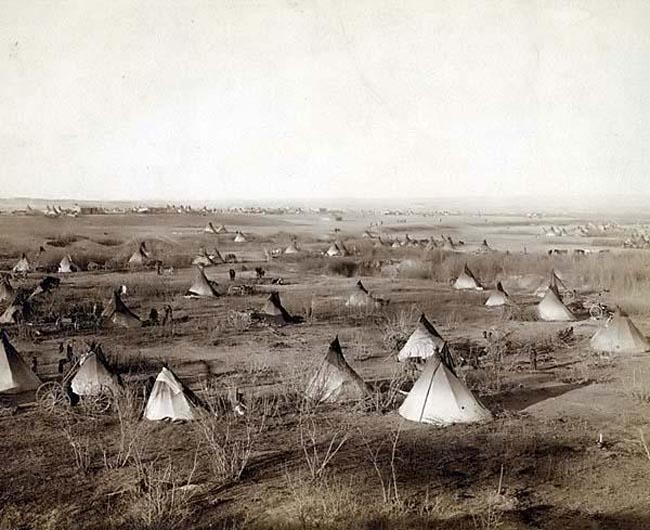

In September a Shoshone Indian, a medicine-man, began to predict the coming of an Indian Messiah. The Great Manitou had taken pity upon his suffering children. The Messiah would roll thirty feet of soil, timbered and sodded, upon their white oppressors, and all who escaped being smothered thereby would become buffaloes and catfish. But all the dead Indians would be restored to life; their hunting-grounds would be as in former days; herds of buffaloes and wild horses would again abound upon the prairies; the Indian millennium would be inaugurated. These glowing predictions were eagerly listened to and believed by large numbers of Indians. Late in October they began a series of ” ghost dances ” in anticipation of the Messiah’s coming; and, to show their devotion, the dancing was continued without intermission for five days and nights. To this hope Sitting Bull gave every encouragement. His adherents arrayed themselves in warpaint, and provided an ample supply of guns and ammunition. They refused to report themselves at the different agencies, and a few of the most desperate began burning and pillaging near Wounded Knee, and afterwards escaped to the Bad Lands.

On Dec. 15 a body of Indian police, acting under orders from General Miles, attempted to arrest Sitting Bull in his camp, about 40 miles northwest of Fort Yates, N. D. A skirmish ensued, and in it the noted chieftain, together with his son Crowfoot and six other Indians, was killed. The remnant of the band made its way to the Bad Lands. On Dec. 28 a battle occurred near Wounded Knee, S. D., between a cavalry regiment and the men of Big Foot’s band. Thirty of the whites were killed, while the Indian dead numbered over 200, including many of their women and children. Over 3,000 Indians then fled from the agency and encamped near White Clay Creek, where, on the next day, another encounter occurred. The result of this engagement was the dispersal of the Indians with heavy loss, and the death of eight soldiers of the 9th Cavalry. Several other skirmishes occurred during the week which followed, with loss of life on both sides. On Jan. 14, 1891, two councils were held with General Miles, and the chiefs, seeing the hopelessness of their cause, agreed to surrender their arms and return to the agency.

The war was practically ended, and on Jan. 21 the greater part of the troops were withdrawn from the neighborhood of the reservation. On the 29th, a delegation of Sioux chiefs, under charge of Agent Lewis, arrived in Washington for the purpose of conferring with the Secretary of the Interior. The conference began on Feb. 7, and continued four days, at the close of which the Indians were received by President Harrison at the White House. They were assured that the cutting down of the congressional appropriation was an accident, and that the government desired faithfully to carry out every agreement made. On their return home the chiefs stopped for a short time at Carlisle, Pa., where the children of several of them were attending school. In 1899 the total number of Sioux was 27,215, divided into nineteen bands, and located principally in South Dakota.