About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

On a hot summer day in 1861, Union and Confederate troops lined up along Bull Run Creek preparing to fight the first major battle of the Civil War. Behind the Confederate lines was the town of Manassas Junction. There the Manassas Gap Railroad came east from the Shenandoah Valley. At Manassas Junction it connected with the Orange and Alexander Railroad as it headed south into central Virginia. The Confederates had amassed a small army under General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard to protect this vital railroad junction.

Union soldiers could hear the sounds of trains arriving behind Confederate lines. Perceptive Northerners knew the sound meant nothing but trouble. Five days earlier the Union army under Brigadier General Irwin McDowell began its slow march out of Washington D.C. As they left Washington, the Union force greatly outnumbered the waiting Confederates. At the time, both sides were operating under the delusion that one great victory would end the war. It appeared that the Federals with their superior numbers were on their way to winning that decisive victory. What the Federals had not anticipated was the Confederate use of railroads.

That summer there were two Confederate army groups in the northern part of Virginia, General Beauregard’s group at Manassas Junction and another under Brigadier General Joseph Eggleston Johnston, protecting the Shenandoah Valley. Johnston’s army was approximately fifty-four miles from Manassas Junction. Johnston was facing the aged Major General Robert Patterson. It was Patterson’s duty to make sure Johnston’s Confederates remained in the Valley away from Manassas. Johnston moved forward leading Patterson to believe he was about to be attacked. In fact, Johnston was marching most of his army of ten thousand eastwards to the town of Piedmont. There the Confederates boarded trains on the Manassas Gap Railroad heading to the Confederate line on Bull Run Creek. Most of the Confederates arrived just in time for the battle. The trip by rail was only thirty-four miles. Although it was a short distance, for an army of recent volunteers it would have been a two or three-day march. By the time of the battle the Confederates had almost as many troops as the attacking Northerners. Among those who rode by rail was a brigade under an eccentric professor from Virginia Military Institute. That brigade delivered the battle’s knockout blow and its general, Brigadier General Thomas Jonathan Jackson, would gain his sobriquet Stonewall.

It was the railroad that gave the Confederates their victory. If the battle had occurred in 1851, the Manassas Gap Railroad would not have existed and the Confederate troops could not have marched to the battle in time.

One historian has written that until the time of the Civil War armies moved no faster than they did in ancient Rome. Logistics, the transportation, quartering and supporting armies was forever changed by the use of railroads. Military tactics were also transformed. Now whole armies could be moved long distances in a few days. In the eastern theater of the war every battle was fought within twenty miles of a railroad or a navigable river. Soon Manassas Junction would join a long list of cities and towns such as Corinth, Chattanooga, Atlanta, and Petersburg which were important railroad junctions and would be the center of much of the fighting during the war. After the Battle of First Bull Run, there could be no doubt that the Civil War would be a railroad war.

Since ancient time, men were aware of the force created by the expansion of heated water into steam. In the late 18th century two events made harnessing steam power possible. James Watts developed a method to convert the oscillating motion of steam engines into a rotary motion to move wheels and with improvements in making iron; steam boilers could be built to withstand the pressures required by steam engines. In the 1820s railroads were developed in both England and America. Railroads represented a technological revolution equal to the recent development of personal computers and the internet. Transportation times were cut as much as ninety per cent. To control traffic, the newly invented telegraph followed the expanding railroads increasing communication to formerly isolated areas.

Railroads were vital to the industrial revolution in America that was beginning prior to the Civil War. Factories were connected to a larger population of potential consumers which provided more jobs and increased production. As businesses and wealth boomed there was an increase in inventors and consumer products. By the end of the 19th century America was transformed from an agrarian society into an industrial giant.

In the 1840s railroads became commercially practicable and by the 1850s there was an explosion of growth in the number of railroads. Nowhere was this growth greater than in the United States. In 1850 there were 9,000 miles of rail in America and by 1860 there were 30,000 miles of rail. The immensity of the American rail system can be illustrated by one fact. The Civil War was fought between two sides that controlled the largest and third largest railroad system in the world. The largest was the Union at 21,000, miles followed by Britain at 10,000 miles and third was the Confederacy at 9,000 miles.

Building railroads required tremendous amounts of capital. Much of the money, especially in the South, came from British bankers. This, as much as the shortage of cotton, was the reason many conservatives in Britain wanted to intervene and mediate a settlement before the warring parties destroyed each other and their railroad collateral.

Compared to the Union the Confederacy had one-third of the freight cars, one fifth of the locomotives, one eighth of rail production, one tenth of the telegraph stations and one twenty fourth of locomotive production. These numbers have led some to say the Confederate rail system was inferior to that of the Union. That is not correct. Soon the Confederate system was in a shambles while the Union system was strengthened. Yet, at the beginning of the war the Confederacy’s railroads were comparable to that of the Union. The Confederacy’s white population of 5.5 million was far smaller than the Union’s 18.5 million. Many Confederate states compared favorably to their Union counterparts when measured in terms of the percentage of population living within fifteen miles or a day’s journey of a railroad. The Confederacy also rated favorably in terms of per capita density of railroad structures such as stations and telegraph lines. During the 1850s most new railroads were built in the south and Midwest making most Confederate railroads newer than those of the northeast. Some of the best engineered railroads were in the South with two of America’s greatest engineering marvels, High Bridge and the Blue Ridge Tunnel being located in Virginia.

Neither Union nor Confederate railroads were ready for a war that would require the long distance transportation of large numbers of men and supplies. Compared to modern railroads Civil War railroads were primitive and dangerous. The rails were made of iron not steel, were much smaller and in need of constant repair. Very few railroads had gravel ballast to stabilize the rails leading to frequent derailments. Prior to the war, railroads were designed for short hauls to bring products to markets in the cities. Few railroads were longer than fifty miles. Among different railroad companies’ lines there was no uniform measurement or gauge of the distance between the two parallel rails of the track. In the North, there were thirteen different track gauges between the various railroads. With different gauges, locomotives and cars of one company could not travel on that of another. It was not until 1886, that all railroad companies adopted the four foot eight and one-half inch standard gauge. Compounding the problem of gauges, tracks of one company were not connected with those of another. At the onset of the war, five railroads were serving Richmond and none was connected. To go from one line to another, passengers had to find transportation across town to the other line. Likewise, freight had to be loaded and unloaded. It has been estimated that to move a regiment from one line to another caused a travel delay of five hours. In the South, little was done to rectify the problem. From a military standpoint when the war began both rail systems were in chaos. The side that could best manage and maintain its railroads was taking a big step towards victory.

When the war began both sides knew railroads would play an important role. There had been other wars where railroads played a part. In the Crimean War (1853 – 56) railroads had limited use for delivering supplies. Prior to the Franco – Austrian War (1859), the French and Piedmontese from Northern Italy had expanded their rail systems expecting an Austrian invasion. When the Austrian invasion came the allies rapidly amassed a large army to crush the Austrian invaders. These wars would not compare to the American Civil War and the extent of the use of railroads during the war. It would be fifty years until the First World War that the use of railroads in warfare would be of the same magnitude as the Civil War.

The first railroad targeted by the Confederates was the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. This railroad ran from Baltimore to Washington then west through slave holding Maryland through the arsenal town of Harpers Ferry crossing through parts of Virginia (now West Virginia) to Ohio. Four days after the attack on Fort Sumter, John Daniel Imboden then a Confederate captain received permission to take Harper’s Ferry and its arsenal. There was a diplomatic problem since Maryland had not yet decided whether it would secede from the Union. Imboden took Harper’s Ferry and then Colonel Thomas J. Jackson was placed in charge of the occupation. Harpers Ferry is located in a deep gorge making it impossible to defend. Jackson knew he would have to abandon the town and after Maryland voted not to secede he was given orders to destroy the railroad and the railroad equipment. Jackson’s taking of fifty-six locomotives and three hundred railroad cars was the largest capture of railroad equipment during the war. Jackson knew the value of the locomotives and the Confederacy’s inability to produce a sufficient number of them. Despite orders to destroy the equipment, Jackson had thirteen locomotives taken forty-eight miles overland by forty horse teams to Strasburg, Virginia the nearest Confederate rail terminal.

Early in the war both sides discovered that the military could not run a railroad. In the spring of 1862, after Confederates realized that Major General George Brinton McClellan intended to attack Richmond by way of the James River, General Joseph E. Johnston moved his army south from Manassas Junction to Richmond. The troops and their supplies were to be moved by way of the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad. Instead of civilian railroad managers, the Quartermaster Corps took charge of the operation. Order soon broke down into such pandemonium that a million pounds of meat which could not be moved had to be burned to keep it from falling into enemy hands.

The greatest movement of troops by rail during the war occurred in July 1862, when General Braxton Bragg moved over 31,000 Confederate troops from Tupelo, Mississippi to Chattanooga, Tennessee. Since it did not lead to an immediate battlefield victory or save a trapped army, this action is not as famous as the Confederate rail movement to Chickamauga or the Union rail advance to Chattanooga. Bragg was Commander of the Army of Mississippi stationed in Tupelo, Mississippi. Union Major General Don Carlos Buell was moving his army to the rail center at Chattanooga. Bragg needed to move his army to protect Chattanooga. The direct route to Chattanooga of 225 miles had been cut off when Federal troops took the rail junction of Corinth, Mississippi after the Battle of Shiloh. Bragg’s route was now 776 miles long. By rail his army traveled south to Mobile, Alabama then to Atlanta and finally to Chattanooga. Despite this circuitous route, Bragg reached Chattanooga in time to stop Buell from taking the city.

At the outset of the war Confederate strategists considered one of their great advantages was the use of interior lines. The Union would have to invade the Confederacy. The advantage of interior lines meant that the defending army could move faster between points than an invading army whose lines were being stretched. By taking one rail junction (Corinth) the Union proved that the value of interior lines could be greatly diminished in a railroad war.

The most important event affecting the Union railroads occurred on January 31, 1862, not on a battlefield but in Congress. Congress passed a bill authorizing President Lincoln as Commander in Chief, “to take possession of any and all railroads and telegraph lines in the United States.” Prior to this bill, administration of Union railroads had been in chaos. This was compounded by Simon Cameron who for the first year of the war was an inept and corrupt head of the War Department. Although the act was rarely used, railroad companies knew that if they did not cooperate they could be taken over by the government. About the same time, Edwin McMasters Stanton was appointed secretary of war. Stanton had been president of the Illinois Central Railroad. He established the United States Military Railroads to control Union railroads where necessary and operate railroads in the occupied South. Colonel Daniel Craig McCallum was appointed director and superintendent. By the end of the war, United States Military Railroads controlled two thousand miles of Confederate railroads and employed ten thousand workers.

Jefferson Davis did not have such power. To properly conduct a war there must be a centralized authority. That concept was an anathema to the Confederate cause of state’s rights and decentralized federal government. Railroad companies in the South had such little respect for the government they would sometimes charge military rates higher than those charged civilians. During the war three men, William Ashe, William Wadley and Frederick Sims was placed in charge of Confederate railroads. Each would find his task impossible due to his lack of authority. Not until February 1865, would the Confederate Congress give Jefferson Davis control of the railroads. By then it was too late.

When Edwin Stanton appointed Daniel McCallum superintendent of the United States Military Railroad he also appointed Herman Haupt as the North’s Chief Railroad Engineer. No man had a greater effect on military railroads in the Civil War than Herman Haupt. Haupt served the Union Army for only fifteen months. Nevertheless, the engineering genius left an indelible mark on the Northern rail system. At the time of the Civil War he was the best known railroad construction engineer in America. Early in 1862, he was embroiled in litigation with the governor of Massachusetts attempting to recoup personal funds he used in constructing the Hoosac Tunnel for the Troy and Greenfield Railroad. That spring, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton called upon Haupt and Daniel McCallum to manage the newly organized U. S. Military Railroad. They worked well together. Haupt took charge of construction and transportation while McCallum worked in the administrative office.

When called up, Haupt would not accept a commission and his title of general was honorary. He would accept no compensation for his services and rarely wore a uniform. Haupt reasoned that this would allow him to be able to get back to Massachusetts to pursue his litigation over the Hoosac Tunnel.

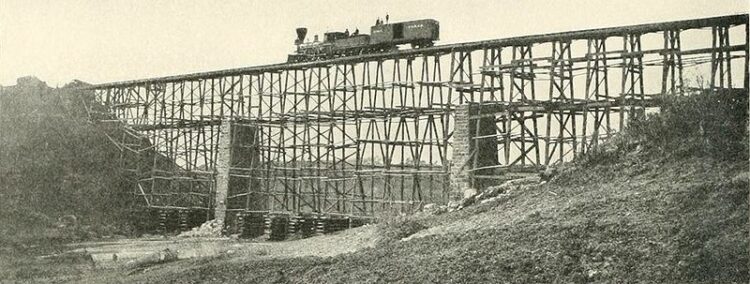

Haupt’s first assignment was to free a stranded army of forty thousand soldiers by rebuilding its railroad. After much delay in the spring of 1862, McClellan began a ponderous offensive movement against Richmond by taking his army down the Chesapeake Bay and marching up the York peninsula. General Irvin McDowell, who lost the Battle of Bull Run, was in command of an army of forty thousand stationed south of Washington D. C. at Aquia Creek Terminal on the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad. As Confederates retreated to Richmond’s defense, they destroyed three miles of railroad and burned two large bridges. McDowell and his army were stranded, unable to assist in the movement towards Richmond. Haupt faced a formidable task and his situation was made worse because his crew consisted of soldiers untrained in railroad construction working with few tools. Despite pouring rain the crews worked around the clock replacing the railroad in three days. Next came the rebuilding of the two destroyed bridges. The Pohick Creek Bridge was one hundred and fifty feet long with a thirty-foot elevation. Within a day the bridge was framed. The far greater challenge was the Potomac Creek Bridge which was almost four hundred feet long with an elevation of eighty feet. Haupt’s construction crew consisted of one hundred and twenty soldiers many of whom were terrified of climbing the high trestles. After nine days of working in the rain, a test train was successfully pulled by ropes over the bridge. Abraham Lincoln and several of his cabinet members came to view the bridge. Later, Lincoln told his War Committee, “That man Haupt has built a bridge across Potomac Creek, about four hundred feet long and nearly one hundred feet high, over which loaded trains are running ever hour and upon my word, gentlemen, there is nothing in it but beanpoles and cornstalks.”

In June of 1862, Haupt reorganized his construction corps. Many laborers brought into the corps were escaped slaves (contrabands) or slaves freed as the Union army moved through the South. Employment of freed slaves began in the first year of the war and was expanded by Haupt. Many were employed in the extensive rail yards that developed in Alexandria, Virginia. Railroads became corridors of protection for escaping slaves and rail junctions became their gathering places. Most provided only menial labor such as chopping wood or working on construction crews, but some became brakemen or firemen on trains. By the end of the war, railroads were probably the largest employer of freedmen in the occupied South.

General McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign ended in retreat and control of the Union army was given to Major General John Pope. The arrogant Pope had no use for railroad managers. Instead, he placed railroad operations under the control of his Quartermaster Department leading Haupt to resign. Soon the railroads were in chaos and the chastened John Pope asked Haupt to return. On August 24, 1862, Haupt was put in control of Pope’s railways. It was too late; on August 26, Stonewall Jackson fell upon Pope’s supply trains at Manassas junction. Through mismanagement trains had been left exposed to attack. Although estimates differ, somewhere between three hundred and four hundred freight cars and seven to eleven locomotives were lost to Jackson and his troops. Even with these losses, Northern industrial might ensured that the losses were soon replaced. The Union learned its lesson and began removing railroads from interference by army officers.

During the Battle of Gettysburg, the closest terminal was at Westminster on the Western Maryland Railroad. From there it was twenty miles by road to the battlefield. The railroad was a single track line with no sidings for long trains, turntables, water stations or telegraph. At best it could handle four trains a day which was totally inadequate to supply the army. Haupt brought in a large crew under his subordinate Adna Anderson to maintain the railroad while Haupt scheduled groups of five trains to come from Baltimore to Westminster on eight hour shifts. The trains brought in fifteen hundred tons of supplies per day and returned with thousands of wounded soldiers. Since there was no turntable at Westminster, trains made the return trip in reverse and water was supplied by bucket brigades from nearby streams.

Two months later, Haupt’s short but brilliant career would be ended by petty politics in the form of Massachusetts governor, John Albion Andrew. In late August, Andrew traveled to Washington to meet with Secretary of War Edmond Stanton to convince Stanton to make Haupt accept an army commission. Governor Andrew knew that if Haupt was an officer he would be unable to return to Massachusetts to continue his case against the state. Wanting to avoid a political confrontation, Stanton caved in and demanded that Haupt accept a commission. Haupt refused and Stanton relieved him of the position. Fortunately for the Union, Haupt’s influence continued in the form of well-trained subordinates who would carry on his work.

Railroads were favorite targets of raiders whether they were army units or guerilla bands. Southwest Virginia produced two thirds of the Confederacy’s salt and one third of its lead which was transported by the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. This railroad was subject to successful and unsuccessful raids every year of the war.

In the South much of the raiding was done by guerilla units which were not part of the regular army. The Confederate Congress authorized the Partisan Ranger Act in early 1862. The act authorized guerilla units to operate along the border and in enemy territory. Colonel John Singleton Mosby was the most prominent of the Confederate guerilla leaders. Unfortunately, many guerilla units viewed the act as a license for theft and murder. It is estimated that during the war there were thirty thousand Confederate guerillas operating near the railroads.

True destruction of railroads was done by large units such as Sherman’s army in its march to the sea. Cavalrymen with few tools and limited time could not do that much damage. Bridges could be burned but even then this could be of limited value. Large bridges had stone pilings which supported wooden spans. Dynamite was not invented until after the Civil War. Since it was next to impossible to quickly destroy the stone pilings the hardest part of rebuilding a bridge was not affected.

No essay on Civil War railroads would be complete without mentioning the Great Locomotive Chase of 1862 and the Northern civilian adventurer James J. Andrews. Andrews and twenty-three men who stole into Georgia wearing civilian clothes knowing they could be shot as spies, if captured. Their purpose was to damage and disrupt the use of the Western and Atlanta Railroad which ran from Atlanta to Chattanooga. The assault began on April 12, one day later than the planned April 11, starting date. In Georgia they boarded a train headed north to Chattanooga pulled by a locomotive named General. The passengers and crew left the train for breakfast at the Big Shanty, Georgia station There Andrews struck taking the locomotive and three boxcars. Stealing a locomotive at Big Shanty was an audacious move since the station was located next to a Confederate camp of four thousand soldiers. Andrews had not anticipated the dogged determination of the train’s conductor, William Allen Fuller. As he ate breakfast, Fuller heard the General leaving the station. Starting on foot and later using a handcar, Fuller began the chase.

Andrews had planned his action by studying railroad schedules to avoid head-on collisions with oncoming trains on the single track railroad. At Etowah Station, Andrews saw a locomotive named the Yonah with its steam up ready to move. The Yonah was old and slow so Andrews didn’t bother to disable her. This was a fatal mistake. At Kingston Georgia, he was delayed while three unscheduled trains came from the opposite direction. Andrews now realized the cost of starting a day late. His action was to be coordinated with an attack by Brigadier General Ormsby McKnight Mitchell towards Chattanooga. Andrews and his men had been delayed by unscheduled Confederate trains attempting to escape General Mitchell’s attack. Conductor Fuller was continuing on Andrew’s trail. Fuller’s handcar was derailed by torn up track, but was soon back on the track. At Etowah, Fuller used the undamaged locomotive, Yonah to continue the chase with the engine running at full throttle. Several times Andrew’s men tore up rails and blocked tracks with rail ties, but they could not burn bridges due to the wet weather. At Kingston, Fuller found himself only five minutes behind Andrews and at Rome, Fuller took over a faster locomotive, the Texas. The Texas had to be driven in reverse. Soon the trains were within sight of each other, traveling at dangerous speeds and only by a miracle the trains did not derail. Andrews unsuccessfully tried to slow Fuller by disconnecting boxcars and leaving them in Fullers’ way. After almost eighty-nine miles, the chase ended when the General ran out of fuel. Although Andrews and his men escaped into the nearby woods, all were soon captured.

The matter ended tragically with Andrews and seven of his men being executed as spies. Six of the raiders were the first soldiers to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor and later almost of the raiders who were soldier received the medal.

Although the raid was of little military value, the Great Locomotive Chase was the most spectacular and famous Civil War action involving trains. Over the years the chase has become shrouded in myths of burning brides, flaming boxcars and running gun battles. Much of that fame came from Hollywood, first by Buster Keaton’s 1926 silent movie comedy, The General and then the 1956 Walt Disney production, The Great Locomotive Chase, starring Fess Parker as Andrews.

In June of 1863 the Union Army of the Cumberland under the command of Major General William Starke Rosecrans, started an eighty-mile march to the vital rail junction at Chattanooga, Tennessee. By a series of brilliant flanking movements, the Federals drove the Confederates under General Braxton Bragg out of Chattanooga into northern Georgia. Confederate leaders in Richmond were well aware that Chattanooga was connected to the Western and Atlantic Railway which led one hundred and thirty- eight miles to Atlanta. If unchecked, General Rosecrans would be in Atlanta a year ahead of Major General William Tecumseh Sherman. Jefferson Davis ordered 13,000 Confederates under Lieutenant General James Longstreet to reinforce General Bragg. Riding a circuitous route over nine hundred and fifty miles of broken down southern rails half of Longstreet’s men arrived in time to join General Bragg and act as the crucial force that brought about the Confederate victory at Chickamauga. After the battle Rosecrans and his Union army retreated to Chattanooga where they were nearly surrounded by Confederates and on the verge of starvation. Almost immediately 23,000 Federals, members of the XI and XII Army Corps, began a seven state more than twelve-hundred-mile rail journey to near Chattanooga. They broke the Confederate siege and during the Battle of Missionary Ridge drove Southern forces away from the city. The next year, Chattanooga with its rail connection became the supply depot for William Sherman’s drive to Atlanta.

No series of campaigns better illustrate the importance of railroads to the military, the deterioration of the Confederate rail system, the Confederate ability to pull a miracle out of a hat, the overwhelming might of Union war-making resources and a stark difference in management styles. Thus the Chickamauga and Chattanooga campaigns are worth a detailed study.

After two months of watching General Rosecrans and his army of 60,000 men maneuver through Tennessee, President Jefferson Davis called a council of war on August 24, 1863. There General Robert E. Lee, Secretary of War James Alexander Sedden and other advisors met with Davis. Despite his crushing defeat at Gettysburg, Lee wanted to again move north looking for that elusive final victory. It may have been that Davis was reluctant to overrule his best general, but it took a full week of discussions before Davis finally decided to send troops from Virginia to the western theater. When asked to lead the units going to Tennessee, Lee declined. Davis, ever the indecisive micromanager, spent almost another week deciding which troops to send and how to send them. Finally, on September 5, Davis ordered General James Longstreet west with his army of 13,000.

While Davis dithered, the troop movement became a logistical problem far worse than first anticipated. The original Confederate route was to be a direct route of five hundred and fifty miles from Richmond into Tennessee by way of Knoxville to Chattanooga. On September 3, this route was cut off. In late summer of 1863, Major General Ambrose Burnside was in Kentucky commanding the 24,000-man Army of Ohio. Burnside had been the commander of Union forces when they suffered the devastating defeat at Fredericksburg. Burnside was directed to move into Tennessee and attack Knoxville while Rosecrans moved towards Chattanooga. As Burnside and his army came through the mountains towards Knoxville, the vastly outnumbered Confederate garrison abandoned the city without a shot being fired. With Knoxville in Union hands, the direct route from Richmond to Chattanooga was cut off. The Confederate troop movement of five hundred and fifty miles suddenly became one of nine hundred and fifty miles. Once again, the Federal’s severing and holding of a small part of a railroad line denied the Confederacy of the advantage of rapid movement on interior lines.

Major Frederick Simms and Quartermaster General Alexander Robert Lawton were in charge of planning the Confederate troop movement. These men had no authority to take command of the Confederate railroads. Lawton and Simms had to go hat in hand asking for help from the civilian managers of the various rail lines. Simms approached the president of the Cheraw and Darlington Railroad asking, “Do you…. need all your engines? I want two good ones for a month or so. Can you let me have them?” The route for the Confederate troops would be long and circuitous. After leaving Richmond, the Confederates divided into two groups that travelled over ten different rail lines. One group traveled through Charlotte, North Carolina and Columbia, South Carolina to reach Atlanta. The other came by way of Wilmington, North Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, and Savannah, Georgia.

On September 9, the first of Longstreet’s troops began the journey west. For the soldiers it would be a cramped, but joyful ride. All along the way soldiers were welcomed by civilians with cheers, good wishes and more importantly often with food. Despite the soldier’s enjoyment, it was a logistical nightmare. There were constant delays caused by breakdowns and accidents. The worst accident was a head on collision of two trains near Cartersville, Georgia. Fourteen to eighteen soldiers were killed and many more were severely injured. The troops traveled two routes over ten different rail lines and made eight transfers of troops due to unconnected or different gauges of tracks. Despite all of the problems, Longstreet and about half of his troops arrived near the Chickamauga battlefield September 19. It was not until September 25 that all of Longstreet’s men arrived. Longstreet arrived on the first day of the Battle of Chickamauga. Fighting on the first day had been indecisive. The arrival of Longstreet and his troops would turn the tide. On the second day the Confederates from Virginia formed the left of the Confederate line. When Federal troops were improperly moved, the aggressive Virginians would exploit the break in the Union line. Had it not been for the valiant stand of Virginia-born Union Major General George Henry Thomas, the Federal army might have been destroyed. As the Federals retreated into Chattanooga, Braxton Bragg refused to follow up his victory and take Chattanooga. Bragg was greatly criticized for this failure. However, he was content to cut off most of the Union supply lines, lay siege and starve out the Federals.

Three days after the battle in Washington, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton received two telegrams from Chattanooga. One was from Assistant Secretary of War and sometime Stanton spy, Charles Anderson Dana and the other came from major general and future president James Abram Garfield. Both messages urged that the government send to Chattanooga twenty to twenty-five thousand troops to save the Army of the Cumberland. Stanton knew that he had to act. Edwin M. Stanton could be arrogant, opinionated and abusive. All that said, he was a person who could get things done. After receiving the messages of Dana and Garfield, Stanton called a meeting of the war council to be held the next day. Stanton came right to the point. General Sherman and his troops were three hundred miles from Chattanooga with the prospect of having to rebuild the railroad as they marched. General Burnside was one hundred and ten miles away still involved with holding Knoxville. At the meeting he stated that thirty thousand troops from Virginia could be transported to Chattanooga in five days. All those at the meeting were stunned. Even the open-minded, Lincoln, had his doubts. Stanton’s argument was simple. If cotton traders could move twenty thousand bales of cotton that distance in five days, the railroads could ship twenty thousand men in the same amount of time. Stanton won his argument and he immediately began telegraphing railroad managers across the country. It had taken Jefferson Davis nearly two weeks to decide to send soldiers and arrange their transport. Stanton had soldiers marching to embarkation points within twelve hours of the meeting and troops boarding trains the morning of the next day, September 25.

The Army of the Potomac’s XI and XII corps made the trip. Both units and their commanders remained in the west and later followed General Sherman through Georgia the next year. Brigadier General Daniel C. McCallum commander of the U.S. Military Railroad was in charge of the movement. McCallum had the power to take over any railroad and he was not afraid to use that power. There would be no going to the railroads hat-in-hand. McCallum and his assistants immediately went to work arranging trains and time schedules for the operation. During the war much had been done to bring the Northern railroads to a standard track gauge. The twelve hundred-mile journey involved only one troop transfer due to incompatible track gauges. This is compared to the eight transfers during the shorter Confederate troop movement to Chickamauga. Although there were mishaps and delays, the movement ran remarkably smoothly with much of this being due to the superior maintenance of the Federal rail system. By October 6, all Union troops had arrived at Bridgeport, Alabama, which was twenty-eight miles from Chattanooga. From there they began the campaign to free Chattanooga, defeat the Confederates at the Battle of Lookout Mountain and drive them into Georgia.

One incident illustrates the single-mindedness of Edwin M. Stanton to see that Union troops were moved as rapidly as possible. Major General Carl Christian Schurz, a former New York politician, was angered when he was placed in a train traveling behind the trains carrying his troops. General Schurz ordered the station master in Graton, West Virginia to stop the 3rd division of the XI Corps until Schurz could join them. The station master refused saying only a direct order from the War Department could stop the movement. Schurz wired Stanton indignant that a mere station master would delay a major general. Stanton’s reply was rapid and explicit. Major general or not, Schurz was threatened with arrest and removal from command if he interfered with the troops’ movement. The trains would go through without delay.

There are several ways to compare the two movements. Confederate troops left Virginia for Chickamauga on September 9, and the last of the troops arrived there sixteen days later on September 25. The Federal troop movement took only eleven days from start to finish. The difference in the efficiency of the two movements is even more remarkable when one considers the Union troops moved over twelve hundred miles as compared to the Confederate nine hundred and fifty miles and that Federals moved twenty-two thousand troops as compared to the Confederate thirteen thousand men. While the Confederate movement was phenomenal, especially given the condition of Confederate, railroads, the Union movement represented the development of a crushing war-making power.

General Longstreet’s Chief of Staff Gilbert Moxley Sorrell made the trip to Chickamauga. He would write, “Never before were so many troops moved over such worn-out railways.” The railroads used by the Confederates on their way to Chickamauga were in the southern heartland and these worn-out railways had not yet seen Union destruction. They were falling apart because the Confederacy could not maintain them.

Had the Civil War ended after the September 1863 Battle of Chickamauga, the Confederacy would have been praised for its use of railroads. First Manassas, Bragg’s movement of thirty thousand troops in 1862 and the Battle of Chickamauga represented decisive use of railroads by the Confederacy. The war did not end in 1863 and the Confederate failure to maintain its railway system was a major contributor to its defeat.

Operation of a railroad requires constant maintenance and replacement of rails and equipment to continue the same level of service. The war’s requirements for the massive movement of men and supplies increased the rate of railroad deterioration. Rails could easily wear out in three years. The Confederate War Department estimated it would need 49,500 tons of new rails each year to maintain its tracks. Prior to the war the South relied heavily on the North and England to provide rails.

There is a belief that southern mills could not produce rail. This is wrong. In 1860, southern mills produced twenty-six thousand tons of rails, but Confederate leaders reduced rail production to zero. All steel production was shifted to armaments, allowing their rail system to slowly deteriorate. For extra rails the Confederacy took rails from smaller lines used to bring agricultural products into cities. This only exacerbated the Confederacy’s inability to move agricultural products and keep its troops fed. It has been estimated that if the siege of Petersburg had lasted another year Lee’s army would have starved to death due to the collapse of the Confederate rail system.

As rail deteriorated, especially after 1863, trains had to go slower meaning more trains were required to keep up the same delivery rates. In contrast, northern mills geared up to phenomenal rates of rail production. By way of example, prior to the Battle of Fredericksburg, Herman Haupt’s construction crew carried an extra ten miles of rail.

Operation of steam locomotives involves water, heat, pressure and the friction of large moving parts which are all enemies of iron. Steam locomotives require regular rebuilding with the replacement of major parts. The Confederacy was short of all those things needed to maintain a locomotive including lubricating oil, gauges, machine tools and skilled mechanics. At the end of 1863, the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad reported it had forty locomotives of which nine were useless and nine were under repair. Although some southern steel mills could produce locomotives, once the war began Confederate locomotive production fell to zero. Again armaments took priority over railroads. The only Confederate source of new locomotives was those stolen during the war.

In late 1864, Confederate Major General Robert Frederick Hoke was ordered to move his division forty-eight miles over the Piedmont Railroad. The first brigade to move took three days by rail and this did not include the time for trains to return. The rest of the division went by foot. By now Confederate soldiers could march faster than they could travel by rail.

Why did Confederate leaders allow such a valuable asset to deteriorate to ruin? Jefferson Davis was well aware of the importance of railroads and he was not uninformed about the problem. All through the war, there were pleas for help from railroad managers. Yet, Davis and other Confederate eiders ignored the pleas. Perhaps they felt the railroads could hold out long enough until Northerners would tire of the war and let the South go its own way. It was not to be.

After the Battle of Lookout Mountain, Abraham Lincoln found his fighting general in Ulysses Grant. Grant was made supreme commander of all Union armies. Grant had long deplored the failure of the various Northern armies to attack in one coordinated action. Grant appointed his friend William T. Sherman commander of the Western theater. Grant would attack Lee in Virginia, while Sherman and his army marched out of Chattanooga, driving south to take Atlanta.

Marching an army of over ninety-eight thousand men south 140 miles into enemy territory presented overwhelming logistical problems. Sherman’s railroad managers were William W. Wright, Anda Anderson and Eben C. Sneed. The three had been Herman Haupt’s best lieutenants. The route from Chattanooga to Atlanta was over the single track Western Atlantic Railroad. The railroad was a narrow corridor in enemy territory that had to be maintained and protected from Confederate guerrilla attack as the main body of the Union army marched on Atlanta.

Sherman began his advance on May 4, 1864. Opposing Sherman was General Joseph E. Johnston. Sherman tried to avoid direct attacks on the Confederate entrenchments. Instead he often made flank marches around Confederate works. These maneuvers forced Johnston to retreat from his fortifications to protect the railroad and prevent Sherman from getting between the Confederates and Atlanta. By July 5, Federals were within sight of Atlanta.

As Sherman moved south, the Union supply line was stretched further and further. It was necessary to rebuild tracks destroyed by retreating Confederates and maintain the overworked line. Blockhouses were built at important points to protect the railroad from marauding southern raiders. Retreating Confederates destroyed the bridge over the Chattahoochee River. The bridge was 780 feet long and 92 feet tall. Under the direction of E. C. Sneed, the bridge was rebuilt in four and one half days in the “beanpole and cornstalk” style of Herman Haupt. An admiring Haupt called it, “this greatest feat of its kind that the world has ever seen.” The railroad was often attacked by Confederate raiders, but Federal ability to rapidly repair the damage made the work of the raiders almost fruitless. When Confederate cavalry blew up a tunnel near Dalton, Georgia, one discouraged soldier commented, “Oh hell, didn’t you know that Sherman carries a duplicate tunnel.”

Jefferson Davis became frustrated with General Johnston’s inability to stop Sherman and as the siege of Atlanta began, Davis replaced Johnston with Lieutenant General John Bell Hood. Hood had lost the use of his arm at Gettysburg and a leg at Chickamauga. He was a hard fighter known for his impetuosity. Sherman was pleased with the move since he thought Hood would come out of his defenses and attack in the open. Hood did not let Sherman down. After a series of battles around Atlanta, the Federals forced the outnumbered Confederates to abandon the city. Contributing to Hood’s decision to leave Atlanta was the fact that Sherman’s army was sweeping around the city cutting its railroads and access to supplies from outside.

After abandoning Atlanta, Hood surprised the Federals by heading north in hopes of cutting the railroad forcing Sherman to retreat from Atlanta to protect his supply line. Sherman’s army was freed of opposition and it could make its march to the sea. Sherman had determined that he could sever his supply lines and march to Savannah his army literally living off the land. In the march to the sea, railroads were a special target of the destructive power of Sherman’s army. After Sherman’s army passed by a railroad all that was left was the embankments.

When he was appointed commander of all Union Armies, Ulysses Grant knew that in the Northern mind, the decisive fight would be against Robert E. Lee in Virginia. Grant stayed with the Army of the Potomac and though Major General Gordon Meade remained in command of the army for the rest of the war the campaign in Virginia was Grant’s. In May of 1864, Grant moved south into Virginia and fought a series of battles in what became known as the Overland Campaign. The Overland Campaign was five weeks of almost constant fighting with three major battles at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Courthouse and Cold Harbor. Despite horrendous losses that would have sent another general retreating to Washington, Grant kept on pushing with dogged determination knowing even if Lee’s losses were far less the South could not replace the soldiers it lost. As Grant moved south the Union Construction Corps followed. In two days in rebuilt fourteen miles of the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad.

Railroads played a crucial role in Grant’s next move. Petersburg, Virginia, a city of eighteen thousand, is located twenty miles south of Richmond. It was the railroad junction for the city of Richmond; four railroads came into Petersburg where they were combined into a single railroad heading to Richmond. If Petersburg fell, Richmond would fall with it.

In June, Grant moved south crossing the James River over a 2,100-foot-long pontoon bridge built by his engineers. The bridge is believed to be the longest ever built in military history. For the first time in the campaign, Grant got the jump on Lee. Lee was unaware of Grant’s move until Union troops were outside Petersburg. A small Confederate garrison stalled the Federal attack until Confederate reinforcements could come and hold the city forcing a siege.

All during the campaign General Grant was aware of the need to deny the Confederacy the use of its railroads. Early in the siege, he sent two divisions of cavalry to destroy rail lines of the Weldon and the Southside Railroads. Grant sent Gen. George Crook to destroy the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad in southwest Virginia. Crook’s men would burn a seven-hundred-foot bridge over the New River at Central Depot, Virginia (now Radford). Major General David Hunter moved down the Shenandoah Valley to destroy the Virginia Central Railroad at Staunton. Hunter then proceeded east, to take the rail junction at Lynchburg. Hunter was stopped because Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal Anderson Early was able to move troops by rail in time to reinforce the troops at Lynchburg. Major General Phil Henry Sheridan was sent to destroy railroads north of Richmond. Although the Confederacy did not have an engineering corps equal to that of the Union, Confederate engineers were somehow able to make enough haphazard repairs to keep the rails open.

In August Federals took control of the Weldon Railroad leaving the Southside Railroad the only line into Petersburg from the south. To supply the army of one hundred thousand, Northerners created a supply center metropolis known as City Point (Hopewell) on the James River. Supplies were brought up the river to City Point and there transferred to a newly built, eighteen-mile-long railroad, bringing provisions close to the siege lines that would stretch thirty miles.

The final attack on Lee’s lines began March 29, 1865. General Philip Sheridan with a cavalry corps and three infantry corps headed west to wrap around the Confederate line and cut the Southside Railroad. The armies met at a crossroads known as Five Forks where a Union victory gave the Federals control of the Southside Railroad. Grant then opened a massive attack on the Confederate lines which soon collapsed forcing the Confederates to abandon both Petersburg and Richmond. In his retreat Lee had hoped to join with the army of Joseph Johnston in North Carolina. Lee headed south along the Richmond, Danville Railroad. The Confederates had been without rations for thirty-six hours when they arrived at Amelia Court House. There they discovered lost orders caused their supply train to contain only ammunition and no food. While Confederates spent the day scouring the countryside for a day looking for food, Federals moved below Amelia Courthouse blocking the Confederate route south along the railroad. Lee was forced to turn west towards Lynchburg generally following the route of the Southside Railroad. The last sizeable battle of the retreat was fought near the town of Farmville. Fittingly, it was a fight over a railroad bridge and engineering marvel known as High Bridge. A supply train full of rations met the Confederates at Farmville. Many soldiers had not been fed when the train suddenly had to leave due to the arrival of Federal cavalry. The Confederate supply train would move west to a terminal known as Appomattox Station. The Confederates would never see the supplies. On April 9, after a failed attempt to break through Union lines, Lee realized that his army was surrounded and he could do nothing but surrender his exhausted army. The surrender occurred in the McLean House in the village of Appomattox Courthouse only a few miles away from the railroad terminal with its desperately needed rations.

At the end of the war, railroads played a role no one would have anticipated – helping a country grieve. It was the sad duty of the railroad to take home the body of the assassinated president. Abraham Lincoln was shot on Good Friday, April 14, 1865. A week later a somber seven car train left Washington for Springfield, Illinois following the same route Lincoln had taken to Washington for his inauguration.

There was an outpouring of grief never before seen in America. Thousands lined the tracks with uncovered heads sadly watching the train pass. In New York, like all cities where the train passed, almost the entire population turned out to mourn the dead president. New York was covered with bunting and banners. The most notable reading, “We shall not look upon his like again.” A procession of thousands followed the casket through Manhattan while several hundred thousand looked on. The train went up the Hudson and west following Lake Erie. At Cleveland a half-million mourners stood in the rain paying their respects. By the time Lincoln was laid to rest in Springfield an estimated seven million people had seen his casket. The train that took Abraham Lincoln home was the last train operated by the United States Military Railroad.