About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

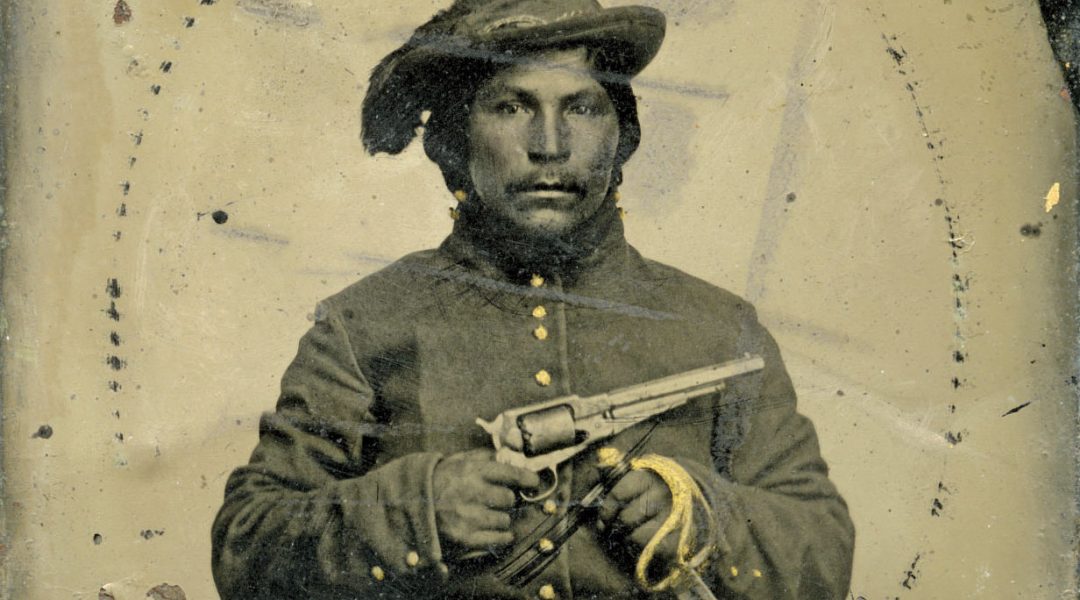

Author: George Bonga

Date:1863

Annotation:

In the midst of the Civil War, a thirty-year conflict began as the federal government sought to concentrate the Plains Indians on reservations. Violence erupted first in Minnesota, where, by 1862, the Santee Sioux were confined to a territory 150 miles long and just 10 miles wide. Denied a yearly payment and agricultural aid promised by treaty, these people rose up in August 1862 and killed more than 350 white settlers at New Ulm. Lincoln appointed John Pope (1822-1892), commander of Union forces at the Second Battle of Bull Run, to crush the uprising. Pope promised to deal with the Sioux “as maniacs or wild beasts, and by no means as people with whom treaties or compromises can be made.” When the Sioux surrendered in September 1862, 1808 were taken prisoner and 303 were condemned to death. Defying threats from Minnesota’s governor and a Senator who warned of the indiscriminate massacre of Indians if all 303 convicted Indians were not executed, Lincoln commuted the sentences of most, but did finally authorize the hanging of 37. This was the largest mass execution in American history, but Lincoln lost many votes in Minnesota as a result of his clemency.

In 1864, fighting spread to Colorado, after the discovery of gold led to an influx of whites. In November, 1864, a group of Colorado volunteers, under the command of Colonel John M. Chivington (1821-1894), fell on a group of Cheyennes at Sand Creek, where they had gathered under the governor’s protection. “We must kill them big and little,” he told his men. “Nits make lice” (nits are the eggs of lice). The militia slaughtered about 150 Cheyenne, mostly women and children.

In this letter, an Ojibway leader describes relations between Indians and missionaries to the clergyman who had helped to persuade Lincoln to commute most of the death sentences in Minnesota.

Document:

…The Missionaries & the Gov[ernmen]t has been trying for many years, to educate & civilize the Ind[ian]…. I am one of the many, who think it almost impossible to civilize the Ind[ian] as long as he inhabits this thick wooded country without a very large expenditure of money…. I have now been 35 years a pretty close observer of Ind[ian] affairs between the Gov[ernmen]t & Missionaries, & the Ind[ian]s. & I have always noticed, that after the Gov[ernmen]t has fulfilled its treaty stipulations about farming, never anything was done by Ind[ians] after, not even to enlarge his own garden. It could not be the expected of Missionaries, to have such large means, so as to show them what benefit they could derive by cultivating the soil and thereby induce them to adopt the habits of the whites.

The Ind[ian] & his father before him have been used to the chase, altho hard work, he is proud of it & thinks to cultivate the soil is only the work of hirelings & squaws & most of the men are ashamed to work in that way. Many a good advice has been given to them, all to no purpose. Starvation will come to him first, before he will cut down trees & dig up roots; when he very well knows it would much better his condition. It would seem, that they can’t perceive, that when their game is all killed off, which is disappearing very fast, they will then have to come down to the very lowest depth of degradation, if they are not exterminated, before that time reaches them….

The little I know of the whites leads me to think, that they will not allow their Ind[ian]s to roam in their midst much longer as well as all the Inds. who live near the white settlements, if the Ind[ian] could be induced to see his own good he would learn that the sooner he was removed from the whites, the better it would be for himself & for his children after him. Having lived the most of my life time with the Ind[ian]s, I easily perceive that the Ind[ian] of today is not the same kind of Ind[ian] that was 40 years ago, altho the same band. In those days we lived and mingled with them, as if we all belonged to one & the same family, our goods often out without lock & key, never fearing anything would go wrong. Far different is it now a days. There is that suspicion on either side, that when we hear of 10 or more Ind[ian]s gathered together, we feel anxious & ask each other, what that can mean, if it is not some bad design & on the Ind[ian] side, they have always some complaint to make. Some imaginary promise that the Gov[ernmen]t has not fulfilled, has led them to that belief, that the whites are combined to try & destroy them. It appears to us all, that there is something smoldering in the breast of the Ind[ian] that it will not take much to set it to a blaze. If that should ever take place, no one can foretell how far the flames will extend…..

Source: Gilder Lehrman Institute

Additional information: George Bonga to the Rev. Henry B. Whipple