About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

The Battle of Antietam /ænˈtiːtəm/ also known as the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the South, fought on Wednesday, September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg, Maryland, and Antietam Creek, as part of the Maryland Campaign, was the first major battle in the American Civil War to take place on Union soil. It is the bloodiest single-day battle in American history, with 22,717 dead, wounded, and missing on both sides combined.[4]

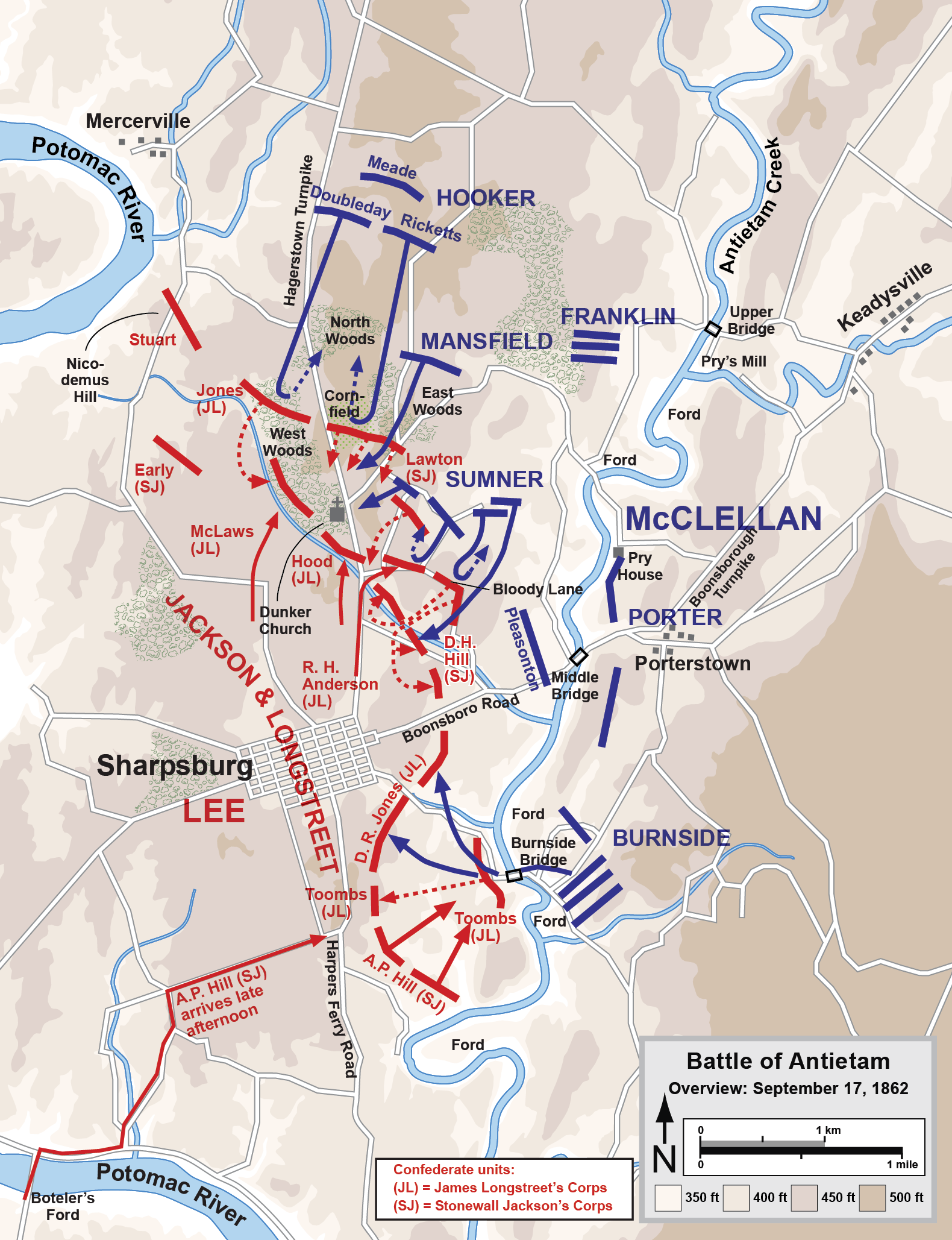

After pursuing Confederate General Robert E. Lee into Maryland, Union Army Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan launched attacks against Lee’s army, in defensive positions behind Antietam Creek. At dawn on September 17, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s corps mounted a powerful assault on Lee’s left flank. Attacks and counterattacks swept across Miller’s cornfield and fighting swirled around the Dunker Church. Union assaults against the Sunken Road eventually pierced the Confederate center, but the Federal advantage was not followed up. In the afternoon, Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s corps entered the action, capturing a stone bridge over Antietam Creek and advancing against the Confederate right. At a crucial moment, Confederate Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill’s division arrived from Harpers Ferry and launched a surprise counterattack, driving back Burnside and ending the battle. Although outnumbered two-to-one, Lee committed his entire force, while McClellan sent in less than three-quarters of his army, enabling Lee to fight the Federals to a standstill. During the night, both armies consolidated their lines. In spite of crippling casualties, Lee continued to skirmish with McClellan throughout September 18, while removing his battered army south of the Potomac River.[5]

Despite having superiority of numbers, McClellan’s attacks failed to achieve force concentration, allowing Lee to counter by shifting forces and moving interior lines to meet each challenge. Despite ample reserve forces that could have been deployed to exploit localized successes, McClellan failed to destroy Lee’s army. McClellan had halted Lee’s invasion of Maryland, but Lee was able to withdraw his army back to Virginia without interference from the cautious McClellan. Although the battle was tactically inconclusive, the Confederate troops had withdrawn first from the battlefield, making it, in military terms, a Union victory. It had significance as enough of a victory to give President Abraham Lincoln the confidence to announce his Emancipation Proclamation, which discouraged the British and French governments from potential plans for recognition of the Confederacy.

Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia—about 55,000 men[6]—entered the state of Maryland on September 3, 1862, following their victory at Second Bull Run on August 30. Emboldened by success, the Confederate leadership intended to take the war into enemy territory. Lee’s invasion of Maryland was intended to run simultaneously with an invasion of Kentucky by the armies of Braxton Bragg and Kirby Smith. It was also necessary for logistical reasons, as northern Virginia’s farms had been stripped bare of food. Based on events such as the Baltimore riots in the spring of 1861 and the fact that President Lincoln had to pass through the city in disguise en route to his inauguration, Confederate leaders assumed that Maryland would welcome the Confederate forces warmly. They sang the tune “Maryland, My Maryland!” as they marched, but by the fall of 1862 pro-Union sentiment was winning out, especially in the western parts of the state. Civilians generally hid inside their houses as Lee’s army passed through their towns, or watched in cold silence, while the Army of the Potomac was cheered and encouraged. Some Confederate politicians, including President Jefferson Davis, believed the prospect of foreign recognition would increase if they won a military victory on Northern soil; such a victory might gain recognition and financial support from Great Britain and France, although there is no evidence that Lee thought the South should base its military plans on this possibility.[7]

While McClellan’s 75,500-man Army of the Potomac was moving to intercept Lee, two Union soldiers (Corporal Barton W. Mitchell and First Sergeant John M. Bloss[8] of the 27th Indiana Volunteer Infantry) discovered a mislaid copy of Lee’s detailed battle plans—Special Order 191—wrapped around three cigars. The order indicated that Lee had divided his army and dispersed portions geographically (to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, and Hagerstown, Maryland), thus making each subject to isolation and defeat if McClellan could move quickly enough. McClellan waited about 18 hours before deciding to take advantage of this intelligence and reposition his forces, thus squandering an opportunity to defeat Lee decisively.[9]

There were two significant engagements in the Maryland campaign prior to the major battle of Antietam: Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s capture of Harpers Ferry and McClellan’s assault through the Blue Ridge Mountains in the Battle of South Mountain. The former was significant because a large portion of Lee’s army was absent from the start of the battle of Antietam, attending to the surrender of the Union garrison; the latter because stout Confederate defenses at two passes through the mountains delayed McClellan’s advance enough for Lee to concentrate the remainder of his army at Sharpsburg.[10]

General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was organized into two large infantry corps.[11] The First Corps, under Maj. Gen. James Longstreet, consisted of the divisions of:

The Second Corps, under Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, consisted of the divisions of:

The remaining units were the Cavalry Corps, under Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, and the reserve artillery, commanded by Brig. Gen. William N. Pendleton. The Second Corps was organized with artillery attached to each division, in contrast to the First Corps, which reserved its artillery at the corps level.

Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac, bolstered by units absorbed from John Pope’s Army of Virginia, included six infantry corps.[12]

The I Corps, under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, consisted of the divisions of:

The II Corps, under Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner, consisted of the divisions of:

The V Corps, under Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter, consisted of the divisions of:

The VI Corps, under Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin, consisted of the divisions of:

The IX Corps, under Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside (Brig. Gen. Jacob D. Cox exercised operational command during the battle), consisted of the divisions of:

The XII Corps, under Maj. Gen. Joseph K. Mansfield, consisted of the divisions of:

The cavalry division of Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton consisted of the brigades of Maj. Charles J. Whiting and Cols. John F. Farnsworth, Richard H. Rush, Andrew T. McReynolds, and Benjamin F. Davis.

Near the town of Sharpsburg, Lee deployed his available forces behind Antietam Creek along a low ridge, starting on September 15. While it was an effective defensive position, it was not an impregnable one. The terrain provided excellent cover for infantrymen, with rail and stone fences, outcroppings of limestone, and little hollows and swales. The creek to their front was only a minor barrier, ranging from 60 to 100 feet (18–30 m) in width, and was fordable in places and crossed by three stone bridges each a mile (1.5 km) apart. It was also a precarious position because the Confederate rear was blocked by the Potomac River and only a single crossing point, Boteler’s Ford at Shepherdstown, was nearby should retreat be necessary. (The ford at Williamsport, Maryland, was 10 miles (16 km) northwest from Sharpsburg and had been used by Jackson in his march to Harpers Ferry. The disposition of Union forces during the battle made it impractical to consider retreating in that direction.) And on September 15, the force under Lee’s immediate command consisted of no more than 18,000 men, only a third the size of the Federal army.[13] The first two Union divisions arrived on the afternoon of September 15 and the bulk of the remainder of the army late that evening. Although an immediate Union attack on the morning of September 16 would have had an overwhelming advantage in numbers, McClellan’s trademark caution and his belief that Lee had as many as 100,000 men at Sharpsburg caused him to delay his attack for a day.[14] This gave the Confederates more time to prepare defensive positions and allowed Longstreet’s corps to arrive from Hagerstown and Jackson’s corps, minus A.P. Hill’s division, to arrive from Harpers Ferry. Jackson defended the left (northern) flank, anchored on the Potomac, Longstreet the right (southern) flank, anchored on the Antietam, a line that was about 4 miles (6 km) long. (As the battle progressed and Lee shifted units, these corps boundaries overlapped considerably.)[15]

On the evening of September 16, McClellan ordered Hooker’s I Corps to cross Antietam Creek and probe the enemy positions. Meade’s division cautiously attacked the Confederates under Hood near the East Woods. After darkness, artillery fire continued as McClellan continued to position his troops. McClellan’s plan was to overwhelm the enemy’s left flank. He arrived at this decision because of the configuration of bridges over the Antietam. The lower bridge (which would soon be named Burnside Bridge) was dominated by Confederate positions on the bluffs overlooking it. The middle bridge, on the road from Boonsboro, was subject to artillery fire from the heights near Sharpsburg. But the upper bridge was 2 miles (3 km) east of the Confederate guns and could be crossed safely. McClellan planned to commit more than half his army to the assault, starting with two corps, supported by a third, and if necessary a fourth. He intended to launch a simultaneous diversionary attack against the Confederate right with a fifth corps, and he was prepared to strike the center with his reserves if either attack succeeded.[16] The skirmish in the East Woods served to signal McClellan’s intentions to Lee, who prepared his defenses accordingly. He shifted men to his left flank and sent urgent messages to his two commanders who had not yet arrived on the battlefield: Lafayette McLaws with two divisions and A.P. Hill with one division.[17]

McClellan’s plans were ill-coordinated and were executed poorly. He issued to each of his subordinate commanders only the orders for his own corps, not general orders describing the entire battle plan. The terrain of the battlefield made it difficult for those commanders to monitor events outside of their sectors, and McClellan’s headquarters were more than a mile in the rear (at the Philip Pry house, east of the creek), making it difficult for him to control the separate corps. Therefore, the battle progressed the next day as essentially three separate, mostly uncoordinated battles: morning in the northern end of the battlefield, midday in the center, and afternoon in the south. This lack of coordination and concentration of McClellan’s forces almost completely nullified the two-to-one advantage the Union enjoyed and allowed Lee to shift his defensive forces to meet each offensive.[18]

The battle opened at dawn (about 5:30 a.m.) on September 17 with an attack down the Hagerstown Turnpike by the Union I Corps under Joseph Hooker. Hooker’s objective was the plateau on which sat the Dunker Church, a modest whitewashed building belonging to a local sect of German Baptists. Hooker had approximately 8,600 men, little more than the 7,700 defenders under Stonewall Jackson, and this slight disparity was more than offset by the Confederates’ strong defensive positions.[19] Abner Doubleday’s division moved on Hooker’s right, James Ricketts’s moved on the left into the East Woods, and George Meade’s Pennsylvania Reserves division deployed in the center and slightly to the rear. Jackson’s defense consisted of the divisions under Alexander Lawton and John R. Jones in line from the West Woods, across the Turnpike, and along the southern end of the Miller Cornfield. Four brigades were held in reserve inside the West Woods.[20]

As the first Union men emerged from the North Woods and into the Cornfield, an artillery duel erupted. Confederate fire was from the horse artillery batteries under Jeb Stuart to the west and four batteries under Col. Stephen D. Lee on the high ground across the pike from the Dunker Church to the south. Union return fire was from nine batteries on the ridge behind the North Woods and twenty 20-pounder Parrott rifles, 2 miles (3 km) east of Antietam Creek. The conflagration caused heavy casualties on both sides and was described by Col. Lee as “artillery Hell.”[21]

Seeing the glint of Confederate bayonets concealed in the Cornfield, Hooker halted his infantry and brought up four batteries of artillery, which fired shell and canister over the heads of the Federal infantry, covering the field. All at once, the cornfield exploded into chaos as a savage battle raged through the area. Men beat each other over the head with rifle butts and stabbed each other with bayonets. Officers rode around on their horses swearing and cursing and yelling orders no one could hear in the noise. Rifles became hot and fouled from too much firing. The air was filled with a hail of bullets and shells.[22]

Meade’s 1st Brigade of Pennsylvanians, under Brig. Gen. Truman Seymour, began advancing through the East Woods and exchanged fire with Colonel James Walker’s brigade of Alabama, Georgia, and North Carolina troops. As Walker’s men forced Seymour’s back, aided by Lee’s artillery fire, Ricketts’s division entered the Cornfield, also to be torn up by artillery. Brig. Gen. Abram Duryée’s brigade marched directly into volleys from Colonel Marcellus Douglass’s Georgia brigade. Enduring heavy fire from a range of 250 yards (230 m) and gaining no advantage because of a lack of reinforcements, Duryée ordered a withdrawal.[20]

The reinforcements that Duryée had expected—brigades under Brig. Gen. George L. Hartsuff and Col. William A. Christian—had difficulties reaching the scene. Hartsuff was wounded by a shell, and Christian dismounted and fled to the rear in terror. When the men were rallied and advanced into the Cornfield, they met the same artillery and infantry fire as their predecessors. As the superior Union numbers began to tell, the Louisiana “Tiger” Brigade under Harry Hays entered the fray and forced the Union men back to the East Woods. The casualties received by the 12th Massachusetts Infantry, 67%, were the highest of any unit that day.[23] The Tigers were beaten back eventually when the Federals brought up a battery of 3-inch ordnance rifles and rolled them directly into the Cornfield, point-blank fire that slaughtered the Tigers, who lost 323 of their 500 men.[24]

…the most deadly fire of the war. Rifles are shot to pieces in the hands of the soldiers, canteens and haversacks are riddled with bullets, the dead and wounded go down in scores.

While the Cornfield remained a bloody stalemate, Federal advances a few hundred yards to the west were more successful. Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s 4th Brigade of Doubleday’s division (recently named the Iron Brigade) began advancing down and astride the turnpike, into the cornfield, and in the West Woods, pushing aside Jackson’s men.[26] They were halted by a charge of 1,150 men from Starke’s brigade, leveling heavy fire from 30 yards (30 m) away. The Confederate brigade withdrew after being exposed to fierce return fire from the Iron Brigade, and Starke was mortally wounded.[27] The Union advance on the Dunker Church resumed and cut a large gap in Jackson’s defensive line, which teetered near collapse. Although the cost was steep, Hooker’s corps was making steady progress.

Confederate reinforcements arrived just after 7 a.m. The divisions under McLaws and Richard H. Anderson arrived following a night march from Harpers Ferry. Around 7:15, General Lee moved George T. Anderson’s Georgia brigade from the right flank of the army to aid Jackson. At 7 a.m., Hood’s division of 2,300 men advanced through the West Woods and pushed the Union troops back through the Cornfield again. The Texans attacked with particular ferocity because as they were called from their reserve position they were forced to interrupt the first hot breakfast they had had in days. They were aided by three brigades of D.H. Hill’s division arriving from the Mumma Farm, southeast of the Cornfield, and by Jubal Early’s brigade, pushing through the West Woods from the Nicodemus Farm, where they had been supporting Jeb Stuart’s horse artillery. Some officers of the Iron Brigade rallied men around the artillery pieces of Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery, and Gibbon himself saw to it that his previous unit did not lose a single caisson.[28] Hood’s men bore the brunt of the fighting, however, and paid a heavy price—60% casualties—but they were able to prevent the defensive line from crumbling and held off the I Corps. When asked by a fellow officer where his division was, Hood replied, “Dead on the field.”[29]

Hooker’s men had also paid heavily but without achieving their objectives. After two hours and 2,500 casualties, they were back where they started. The Cornfield, an area about 250 yards (230 m) deep and 400 yards (400 m) wide, was a scene of indescribable destruction. It was estimated that the Cornfield changed hands no fewer than 15 times in the course of the morning.[30] Major Rufus R. Dawes, who assumed command of Iron Brigade’s 6th Wisconsin Regiment during the battle, later compared the fighting around the Hagerstown Turnpike with the stone wall at Fredericksburg, Spotsylvania’s “Bloody Angle”, and the slaughter pen of Cold Harbor, insisting that “the Antietam Turnpike surpassed them all in manifest evidence of slaughter.”[31] Hooker called for support from the 7,200 men of Mansfield’s XII Corps.

… every stalk of corn in the northern and greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the [Confederates] slain lay in rows precisely as they had stood in their ranks a few moments before.

Half of Mansfield’s men were raw recruits, and Mansfield was also inexperienced, having taken command only two days before. Although he was a veteran of 40 years’ service, he had never led large numbers of soldiers in combat. Concerned that his men would bolt under fire, he marched them in a formation that was known as “column of companies, closed in mass,” a bunched-up formation in which a regiment was arrayed ten ranks deep instead of the normal two. As his men entered the East Woods, they presented an excellent artillery target, “almost as good a target as a barn.” Mansfield himself was shot in the stomach and died the next day. Alpheus Williams assumed temporary command of the XII Corps.[32]

The new recruits of Mansfield’s 1st Division made no progress against Hood’s line, which was reinforced by brigades of D.H. Hill’s division under Colquitt and McRae. The 2nd Division of the XII Corps, under George Sears Greene, however, broke through McRae’s men, who fled under the mistaken belief that they were about to be trapped by a flanking attack. This breach of the line forced Hood and his men, outnumbered, to regroup in the West Woods, where they had started the day.[23] Greene was able to reach the Dunker Church, Hooker’s original objective, and drove off Stephen Lee’s batteries. Federal forces held most of the ground to the east of the turnpike.

Hooker attempted to gather the scattered remnants of his I Corps to continue the assault, but a Confederate sharpshooter spotted the general’s conspicuous white horse and shot Hooker through the foot. Command of his I Corps fell to General Meade, since Hooker’s senior subordinate, James B. Ricketts, had also been wounded. But with Hooker removed from the field, there was no general left with the authority to rally the men of the I and XII Corps. Greene’s men came under heavy fire from the West Woods and withdrew from the Dunker Church.

In an effort to turn the Confederate left flank and relieve the pressure on Mansfield’s men, Sumner’s II Corps was ordered at 7:20 a.m. to send two divisions into battle. Sedgwick’s division of 5,400 men was the first to ford the Antietam, and they entered the East Woods with the intention of turning left and forcing the Confederates south into the assault of Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps. But the plan went awry. They became separated from William H. French’s division, and at 9 a.m. Sumner, who was accompanying the division, launched the attack with an unusual battle formation—the three brigades in three long lines, men side-by-side, with only 50 to 70 yards (60 m) separating the lines. They were assaulted first by Confederate artillery and then from three sides by the divisions of Early, Walker, and McLaws, and in less than half an hour Sedgwick’s men were forced to retreat in great disorder to their starting point with over 2,200 casualties, including Sedgwick himself, who was taken out of action for several months by a wound.[33] Sumner has been condemned by most historians for his “reckless” attack, his lack of coordination with the I and XII Corps headquarters, losing control of French’s division when he accompanied Sedgwick’s, failing to perform adequate reconnaissance prior to launching his attack, and selecting the unusual battle formation that was so effectively flanked by the Confederate counterattack. Historian M.V. Armstrong’s recent scholarship, however, has determined that Sumner did perform appropriate reconnaissance and his decision to attack where he did was justified by the information available to him.[34]

The final actions in the morning phase of the battle were around 10 a.m., when two regiments of the XII Corps advanced, only to be confronted by the division of John G. Walker, newly arrived from the Confederate right. They fought in the area between the Cornfield in the West Woods, but soon Walker’s men were forced back by two brigades of Greene’s division, and the Federal troops seized some ground in the West Woods.

The morning phase ended with casualties on both sides of almost 13,000, including two Union corps commanders.[35]

By midday, the action had shifted to the center of the Confederate line. Sumner had accompanied the morning attack of Sedgwick’s division, but another of his divisions, under French, lost contact with Sumner and Sedgwick and inexplicably headed south. Eager for an opportunity to see combat, French found skirmishers in his path and ordered his men forward. By this time, Sumner’s aide (and son) located French, described the terrible fighting in the West Woods and relayed an order for him to divert Confederate attention by attacking their center.[36]

French confronted D.H. Hill’s division. Hill commanded about 2,500 men, less than half the number under French, and three of his five brigades had been torn up during the morning combat. This sector of Longstreet’s line was theoretically the weakest. But Hill’s men were in a strong defensive position, atop a gradual ridge, in a sunken road worn down by years of wagon traffic, which formed a natural trench.[37]

French launched a series of brigade-sized assaults against Hill’s improvised breastworks at around 9:30 a.m. The first brigade to attack, mostly inexperienced troops commanded by Brig. Gen. Max Weber, was quickly cut down by heavy rifle fire; neither side deployed artillery at this point. The second attack, more raw recruits under Col. Dwight Morris, was also subjected to heavy fire but managed to beat back a counterattack by the Alabama Brigade of Robert Rodes. The third, under Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball, included three veteran regiments, but they also fell to fire from the sunken road. French’s division suffered 1,750 casualties (of his 5,700 men) in under an hour.[38]

Reinforcements were arriving on both sides, and by 10:30 a.m. Robert E. Lee sent his final reserve division—some 3,400 men under Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson—to bolster Hill’s line and extend it to the right, preparing an attack that would envelop French’s left flank. But at the same time, the 4,000 men of Maj. Gen. Israel B. Richardson’s division arrived on French’s left. This was the last of Sumner’s three divisions, which had been held up in the rear by McClellan as he organized his reserve forces.[39] Richardson’s fresh troops struck the first blow.

Leading off the fourth attack of the day against the sunken road was the Irish Brigade of Brig. Gen. Thomas F. Meagher. As they advanced with emerald green flags snapping in the breeze, a regimental chaplain, Father William Corby, rode back and forth across the front of the formation shouting words of conditional absolution prescribed by the Roman Catholic Church for those who were about to die. (Corby would later perform a similar service at Gettysburg in 1863.) The mostly Irish immigrants lost 540 men to heavy volleys before they were ordered to withdraw.[40]

Gen. Richardson personally dispatched the brigade of Brig. Gen. John C. Caldwell into battle around noon (after being told that Caldwell was in the rear, behind a haystack), and finally the tide turned. Anderson’s Confederate division had been little help to the defenders after Gen. Anderson was wounded early in the fighting. Other key leaders were lost as well, including George B. Anderson (no relation; Anderson’s successor, Col. Charles C. Tew of the 2nd North Carolina, was killed minutes after assuming command)[41] and Col. John B. Gordon of the 6th Alabama. (Gordon received 5 serious wounds in the fight, twice in his right leg, twice in the left arm, and once in the face. He lay unconscious, face down in his cap, and later told colleagues that he should have smothered in his own blood, except for the act of an unidentified Yankee, who had earlier shot a hole in his cap, which allowed the blood to drain.)[42] Rodes was wounded in the thigh but was still on the field. These losses contributed directly to the confusion of the following events.

We were shooting them like sheep in a pen. If a bullet missed the mark at first it was liable to strike the further bank, angle back, and take them secondarily.

As Caldwell’s brigade advanced around the right flank of the Confederates, Col. Francis C. Barlow and 350 men of the 61st and 64th New York saw a weak point in the line and seized a knoll commanding the sunken road. This allowed them to get enfilade fire into the Confederate line, turning it into a deadly trap. In attempting to wheel around to meet this threat, a command from Rodes was misunderstood by Lt. Col. James N. Lightfoot, who had succeeded the unconscious John Gordon. Lightfoot ordered his men to about-face and march away, an order that all five regiments of the brigade thought applied to them as well. Confederate troops streamed toward Sharpsburg, their line lost.

Richardson’s men were in hot pursuit when massed artillery hastily assembled by Gen. Longstreet drove them back. A counterattack with 200 men led by D.H. Hill got around the Federal left flank near the sunken road, and although they were driven back by a fierce charge of the 5th New Hampshire, this stemmed the collapse of the center. Reluctantly, Richardson ordered his division to fall back to north of the ridge facing the sunken road. His division lost about 1,000 men. Col. Barlow was severely wounded, and Richardson mortally wounded.[44] Winfield S. Hancock assumed division command. Although Hancock would have an excellent future reputation as an aggressive division and corps commander, the unexpected change of command sapped the momentum of the Federal advance.[45]

The carnage from 9:30 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. on the sunken road gave it the name Bloody Lane, leaving about 5,600 casualties (Union 3,000, Confederate 2,600) along the 800-yard (700 m) road. And yet a great opportunity presented itself. If this broken sector of the Confederate line were exploited, Lee’s army would have been divided in half and possibly defeated. There were ample forces available to do so. There was a reserve of 3,500 cavalry and the 10,300 infantrymen of Gen. Porter’s V Corps, waiting near the middle bridge, a mile away. The VI Corps had just arrived with 12,000 men. Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin of the VI Corps was ready to exploit this breakthrough, but Sumner, the senior corps commander, ordered him not to advance. Franklin appealed to McClellan, who left his headquarters in the rear to hear both arguments but backed Sumner’s decision, ordering Franklin and Hancock to hold their positions.[46] Later in the day, the commander of the other reserve unit near the center, the V Corps, Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter, heard recommendations from Maj. Gen. George Sykes, commanding his 2nd Division, that another attack be made in the center, an idea that intrigued McClellan. However, Porter is said to have told McClellan, “Remember, General, I command the last reserve of the last Army of the Republic.” McClellan demurred and another opportunity was lost.[47]

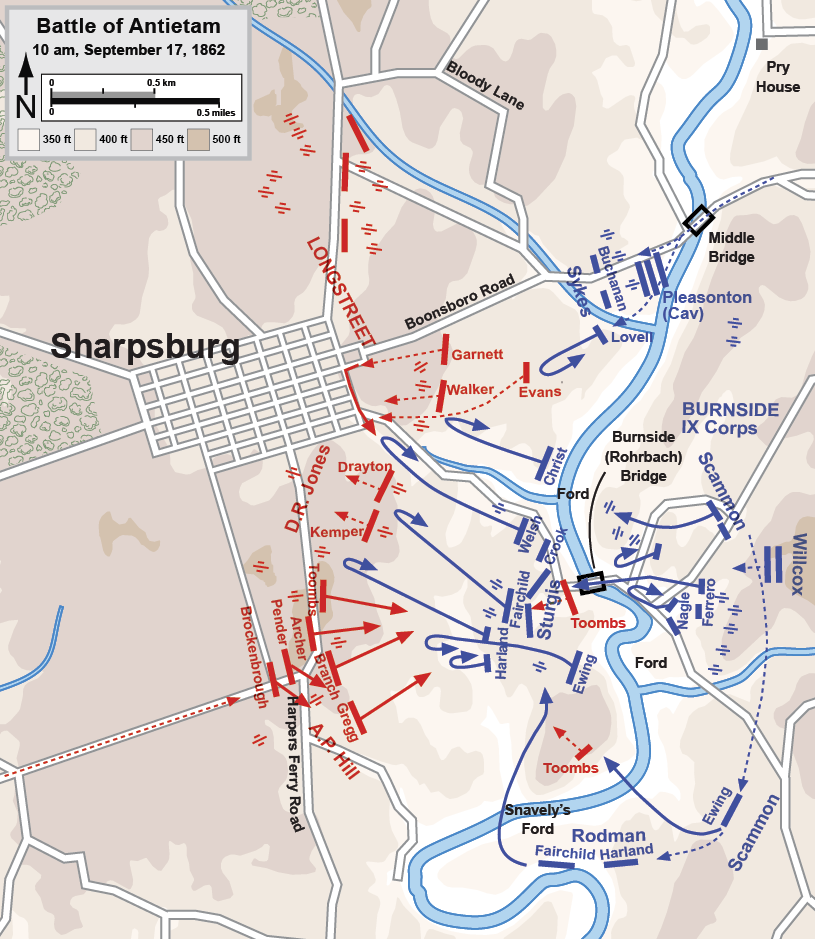

The action moved to the southern end of the battlefield. McClellan’s plan called for Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside and the IX Corps to conduct a diversionary attack in support of Hooker’s I Corps, hoping to draw Confederate attention away from the intended main attack in the north. However, Burnside was instructed to wait for explicit orders before launching his attack, and those orders did not reach him until 10 a.m.[48] Burnside was strangely passive during preparations for the battle. He was disgruntled that McClellan had abandoned the previous arrangement of “wing” commanders reporting to him. Previously, Burnside had commanded a wing that included both the I and IX Corps and now he was responsible only for the IX Corps. Implicitly refusing to give up his higher authority, Burnside treated first Maj. Gen. Jesse L. Reno (killed at South Mountain) and then Brig. Gen. Jacob D. Cox of the Kanawha Division as the corps commander, funneling orders to the corps through him.

Burnside had four divisions (12,500 troops) and 50 guns east of Antietam Creek. Facing him was a force that had been greatly depleted by Lee’s movement of units to bolster the Confederate left flank. At dawn, the divisions of Brig. Gens. David R. Jones and John G. Walker stood in defense, but by 10 a.m. all of Walker’s men and Col. George T. Anderson’s Georgia brigade had been removed. Jones had only about 3,000 men and 12 guns available to meet Burnside. Four thin brigades guarded the ridges near Sharpsburg, primarily a low plateau known as Cemetery Hill. The remaining 400 men—the 2nd and 20th Georgia regiments, under the command of Brig. Gen. Robert Toombs, with two artillery batteries—defended Rohrbach’s Bridge, a three-span, 125-foot (38 m) stone structure that was the southernmost crossing of the Antietam.[49] It would become known to history as Burnside’s Bridge because of the notoriety of the coming battle. The bridge was a difficult objective. The road leading to it ran parallel to the creek and was exposed to enemy fire. The bridge was dominated by a 100-foot (30 m) high wooded bluff on the west bank, strewn with boulders from an old quarry, making infantry and sharpshooter fire from good covered positions a dangerous impediment to crossing.

Go and look at [Burnside’s Bridge], and tell me if you don’t think Burnside and his corps might have executed a hop, skip, and jump and landed on the other side. One thing is certain, they might have waded it that day without getting their waist belts wet in any place.

Antietam Creek in this sector was seldom more than 50 feet (15 m) wide, and several stretches were only waist deep and out of Confederate range. Burnside has been widely criticized for ignoring this fact, starting with derision from Confederate staff officer Henry Kyd Douglas.[50] However, the commanding terrain across the sometimes shallow creek made crossing the water a comparatively easy part of a difficult problem. Burnside concentrated his plan instead on storming the bridge while simultaneously crossing a ford McClellan’s engineers had identified a half mile (1 km) downstream, but when Burnside’s men reached it, they found the banks too high to negotiate. While Col. George Crook’s Ohio brigade prepared to attack the bridge with the support of Brig. Gen. Samuel Sturgis’s division, the rest of the Kanawha Division and Brig. Gen. Isaac Rodman’s division struggled through thick brush trying to locate Snavely’s Ford, 2 miles (3 km) downstream, intending to flank the Confederates.[51]

Crook’s assault on the bridge was led by skirmishers from the 11th Connecticut, who were ordered to clear the bridge for the Ohioans to cross and assault the bluff. After receiving punishing fire for 15 minutes, the Connecticut men withdrew with 139 casualties, one-third of their strength, including their commander, Col. Henry W. Kingsbury, who was fatally wounded.[52] Crook’s main assault went awry when his unfamiliarity with the terrain caused his men to reach the creek a quarter mile (400 m) upstream from the bridge, where they exchanged volleys with Confederate skirmishers for the next few hours.[53]

While Rodman’s division was out of touch, slogging toward Snavely’s Ford, Burnside and Cox directed a second assault at the bridge by one of Sturgis’s brigades, led by the 2nd Maryland and 6th New Hampshire. They also fell prey to the Confederate sharpshooters and artillery, and their attack fell apart.[54] By this time it was noon, and McClellan was losing patience. He sent a succession of couriers to motivate Burnside to move forward. He ordered one aide, “Tell him if it costs 10,000 men he must go now.” He increased the pressure by sending his inspector general, Col. Delos B. Sackett, to confront Burnside, who reacted indignantly: “McClellan appears to think I am not trying my best to carry this bridge; you are the third or fourth one who has been to me this morning with similar orders.”[55]

The third attempt to take the bridge was at 12:30 p.m. by Sturgis’s other brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero. It was led by the 51st New York and the 51st Pennsylvania, who, with adequate artillery support and a promise that a recently canceled whiskey ration would be restored if they were successful, charged downhill and took up positions on the east bank. Maneuvering a captured light howitzer into position, they fired double canister down the bridge and got within 25 yards (23 m) of the enemy. By 1 p.m., Confederate ammunition was running low, and word reached Toombs that Rodman’s men were crossing Snavely’s Ford on their flank. He ordered a withdrawal. His Georgians had cost the Federals more than 500 casualties, giving up fewer than 160 themselves. And they had stalled Burnside’s assault on the southern flank for more than three hours.[56]

Burnside’s assault stalled again on its own. His officers had neglected to transport ammunition across the bridge, which was itself becoming a bottleneck for soldiers, artillery, and wagons. This represented another two-hour delay. Gen. Lee used this time to bolster his right flank. He ordered up every available artillery unit, although he made no attempt to strengthen D.R. Jones’s badly outnumbered force with infantry units from the left. Instead, he counted on the arrival of A.P. Hill’s Light Division, currently embarked on an exhausting 17 mile (27 km) march from Harpers Ferry. By 2 p.m., Hill’s men had reached Boteler’s Ford, and Hill was able to confer with the relieved Lee at 2:30, who ordered him to bring up his men to the right of Jones.[57]

The Federals were completely unaware that 3,000 new men would be facing them. Burnside’s plan was to move around the weakened Confederate right flank, converge on Sharpsburg, and cut Lee’s army off from Boteler’s Ford, their only escape route across the Potomac. At 3 p.m., Burnside left Sturgis’s division in reserve on the west bank and moved west with over 8,000 troops (most of them fresh) and 22 guns for close support.[58]

An initial assault led by the 79th New York “Cameron Highlanders” succeeded against Jones’s outnumbered division, which was pushed back past Cemetery Hill and to within 200 yards (200 m) of Sharpsburg. Farther to the left, Rodman’s division advanced toward Harpers Ferry Road. Its lead brigade, under Col. Harrison Fairchild, containing several colorful Hawkins’ Zouaves of the 9th New York, came under heavy shellfire from a dozen enemy guns mounted on a ridge to their front, but they kept pushing forward. There was panic in the streets of Sharpsburg, clogged with retreating Confederates. Of the five brigades in Jones’s division, only Toombs’s brigade was still intact, but he had only 700 men.[59]

A. P. Hill’s division arrived at 3:30 p.m. Hill divided his column, with two brigades moving southeast to guard his flank and the other three, about 2,000 men, moving to the right of Toombs’s brigade and preparing for a counterattack. At 3:40 p.m., Brig. Gen. Maxcy Gregg’s brigade of South Carolinians attacked the 16th Connecticut on Rodman’s left flank in the cornfield of farmer John Otto. The Connecticut men had been in service for only three weeks, and their line disintegrated with 185 casualties. The 4th Rhode Island came up on the right, but they had poor visibility amid the high stalks of corn, and they were disoriented because many of the Confederates were wearing Union uniforms captured at Harpers Ferry. They also broke and ran, leaving the 8th Connecticut far out in advance and isolated. They were enveloped and driven down the hills toward Antietam Creek. A counterattack by regiments from the Kanawha Division fell short.[60]

The IX Corps had suffered casualties of about 20% but still possessed twice the number of Confederates confronting them. Unnerved by the collapse of his flank, Burnside ordered his men all the way back to the west bank of the Antietam, where he urgently requested more men and guns. McClellan was able to provide just one battery. He said, “I can do nothing more. I have no infantry.” In fact, however, McClellan had two fresh corps in reserve, Porter’s V and Franklin’s VI, but he was too cautious, concerned he was greatly outnumbered and that a massive counterstrike by Lee was imminent. Burnside’s men spent the rest of the day guarding the bridge they had suffered so much to capture.[61]

The battle was over by 5:30 p.m. Losses for the day were heavy on both sides. The Union had 12,401 casualties with 2,108 dead. Confederate casualties were 10,318 with 1,546 dead. This represented 25% of the Federal force and 31% of the Confederate.[3] More Americans died in battle on September 17, 1862, than on any other day in the nation’s military history.[63] Several generals died as a result of the battle, including Maj. Gens. Joseph K. Mansfield and Israel B. Richardson and Brig. Gen. Isaac P. Rodman on the Union side (all mortally wounded), and Brig. Gens. Lawrence O. Branch and William E. Starke on the Confederate side (killed).[64] Brigadier General George B. Anderson got shot in the ankle during the defense of the Bloody Lane. He survived the battle wounded but later on in October he died after the inevitable amputation.

On the morning of September 18, Lee’s army prepared to defend against a Federal assault that never came. After an improvised truce for both sides to recover and exchange their wounded, Lee’s forces began withdrawing across the Potomac that evening to return to Virginia.[65]

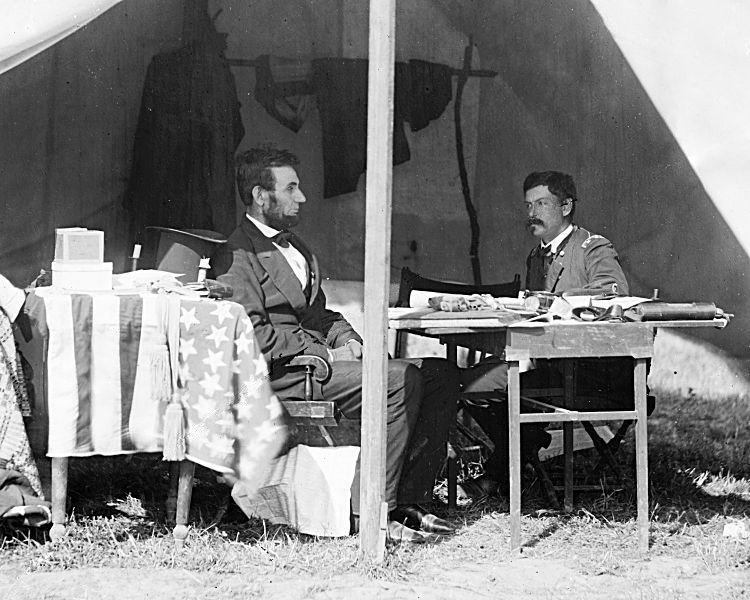

President Lincoln was disappointed in McClellan’s performance. He believed that McClellan’s cautious and poorly coordinated actions in the field had forced the battle to a draw rather than a crippling Confederate defeat. Historian Stephen Sears agrees.[66]

In making his battle against great odds to save the Republic, General McClellan had committed barely 50,000 infantry and artillerymen to the contest. A third of his army did not fire a shot. Even at that, his men repeatedly drove the Army of Northern Virginia to the brink of disaster, feats of valor entirely lost on a commander thinking of little beyond staving off his own defeat.— Stephen W. Sears, Landscape Turned Red

The president was even more astonished that from September 17 to October 26, despite repeated entreaties from the War Department and the president himself, McClellan declined to pursue Lee across the Potomac, citing shortages of equipment and the fear of overextending his forces. General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck wrote in his official report, “The long inactivity of so large an army in the face of a defeated foe, and during the most favorable season for rapid movements and a vigorous campaign, was a matter of great disappointment and regret.”[67] Lincoln relieved McClellan of his command of the Army of the Potomac on November 7, effectively ending the general’s military career.

Some students of history question the designation of “strategic victory” for the Union. After all, it can be argued that McClellan performed poorly in the campaign and the battle itself, and Lee displayed great generalship in holding his own in battle against an army that greatly outnumbered his. Casualties were comparable on both sides, although Lee lost a higher percentage of his army. Lee withdrew from the battlefield first, the technical definition of the tactical loser in a Civil War battle. However, in a strategic sense, despite being a tactical draw, Antietam is considered a turning point of the war and a victory for the Union because it ended Lee’s strategic campaign (his first invasion of the North). Historian James M. McPherson summed up the importance of Antietam in his Crossroads of Freedom:[68]

No other campaign and battle in the war had such momentous, multiple consequences as Antietam. In July 1863 the dual Union triumphs at Gettysburg and Vicksburg struck another blow that blunted a renewed Confederate offensive in the East and cut off the western third of the Confederacy from the rest. In September 1864 Sherman’s capture of Atlanta reversed another decline in Northern morale and set the stage for the final drive to Union victory. These also were pivotal moments. But they would never have happened if the triple Confederate offensives in Mississippi, Kentucky, and most of all Maryland had not been defeated in the fall of 1862.— James M. McPherson, Crossroads of Freedom

The results of Antietam also allowed President Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, which took effect on January 1, 1863. Although Lincoln had intended to do so earlier, he was advised by his Cabinet to make this announcement after a Union victory to avoid the perception that it was issued out of desperation (since the Confederates had the upper edge in the war prior to Antietam). The Union victory and Lincoln’s proclamation played a considerable role in dissuading the governments of France and Britain from recognizing the Confederacy; some suspected they were planning to do so in the aftermath of another Union defeat. When the issue of emancipation was linked to the progress of the war, neither government had the political will to oppose the United States, since it linked support to the South to support for slavery. Both countries had already abolished slavery, and the public would not have tolerated the government militarily supporting a sovereignty upholding the ideals of slavery.[69]

Conservation work undertaken by Antietam National Battlefield and private groups, has earned Antietam a reputation as one of the nation’s best preserved Civil War battlefields. Few visual intrusions mar the landscape, letting visitors experience the site nearly as it was in 1862.[70] Antietam was one of the first five Civil War battlefields preserved federally, receiving that distinction on August 30, 1890. The U.S. War Department also placed over 300 tablets at that time to mark the spots of individual regiments and of significant phases in the battle. The battlefield was transferred to the Department of the Interior in 1933. The Antietam National Battlefield now consists of 2,743 acres, while the Civil War Trust has preserved 240 acres around the site.[71]

In October 2012, the National Museum of Civil War Medicine displayed 21 original Mathew Brady 1862 photographs documenting the Battle of Antietam. Brady is considered the father of photojournalism.[72] He is known for his efforts to document the Civil War on a grand scale by bringing his photographic studio to the battlefields after receiving special permission from Lincoln in 1861.[73] On September 19, 1862, two days after the Battle of Antietam, Mathew Brady sent photographer Alexander Gardner and his assistant James Gibson[74] to photograph the carnage. In October 1862 Brady displayed the photos by Gardner in an exhibition entitled “The Dead of Antietam” at Brady’s New York gallery. Many images in this presentation were graphic photographs of corpses, a presentation new to America. This was the first time that many Americans saw the realities of war in photographs as distinct from previous “artists’ impressions”.[75] The New York Times published a review on October 20, 1862, describing how, “Of all objects of horror one would think the battle-field should stand preeminent, that it should bear away the palm of repulsiveness.” But crowds came to the gallery drawn by a “terrible fascination” to the images of mangled corpses which brought the reality of remote battle fields to New Yorkers. Viewers examined details using a magnifying glass. “We would scarce choose to be in the gallery, when one of the women bending over them should recognize a husband, a son, or a brother in the still, lifeless lines of bodies, that lie ready for the gaping trenches.”[76]

Captain James Hope of the 2nd Vermont Infantry, a professional artist, painted five large murals based on battlefield scenes he had sketched during the Battle of Antietam. He had been assigned to sideline duties as a scout and mapmaker due to his injuries. The canvasses were exhibited in his gallery in Watkins Glen, New York, until his death in 1892. He had prints made of these larger paintings and sold the reproductions. In the 1930s his work was damaged in a flood. The original murals were shown in a church for many years. In 1979, the National Park Service purchased and restored them.[77][78] They were featured in a 1984 Time-Life book entitled The Bloodiest Day: The Battle of Antietam.[79]