About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

The First Battle of Boonville was a minor skirmish of the American Civil War, occurring on June 17, 1861, near Boonville in Cooper County, Missouri. Although casualties were extremely light, the battle’s strategic impact was far greater than one might assume from its limited nature. The Union victory established what would become an unbroken Federal control of the Missouri River, and helped to thwart efforts to bring Missouri into the Confederacy.

Four battles were fought at Boonville during the Civil War: the first battle forms the main subject of this article, while the others are described below under other battles at Boonville.

At the onset of the Civil War, Missouri, like many border states in the Union, was deeply divided over whether to support the United States under Abraham Lincoln, or join the nascent Confederacy under Jefferson Davis. Claiborne F. Jackson, the pro-Southern governor, wanted his state to secede, but Missouri’s overall sentiment was initially neutral. An elected State convention did not pass a secession ordinance, as Jackson had hoped it might.

However, pro-secession elements did not let this setback dissuade them. They seized the small Federal armory in Liberty, Missouri, planning to subsequently confiscate a much more sizable stock of weapons located at the St. Louis Arsenal. This plot was temporarily thwarted by an energetic young officer, Captain Nathaniel Lyon. Lyon allied himself with Missouri Congressman Frank Blair and anti-slavery German immigrants in St. Louis to secure the arsenal for the Union. In the process, Lyon used a mixed force of U.S. Army Regulars and Federally enrolled Missouri Volunteers (mostly ethnic Germans) to capture the Missouri Volunteer Militia (MVM) which had assembled (purportedly for an innocuous annual drill) at Camp Jackson on the outskirts of St. Louis on May 10, 1861.

When Lyon unwisely attempted to march his prisoners through the streets of St. Louis, a deadly riot erupted. The Missouri General Assembly, far more secessionist than the state’s population at that time,[1] convened an emergency session that night, and passed a series of emergency bills creating the Missouri State Guard, and granting Governor Jackson near-dictatorial powers to take any actions necessary to “repel invasion” (by Federal forces) and “suppress insurrection” (by Missourians enlisted in Federal forces).[2] The new State Guard began organizing statewide in nine decentralized military districts, initially structured around the independent militia companies of the pre-Camp Jackson MVM. State Guard authorities also worked to manage the large numbers of volunteers who flooded into Jefferson City to protect the state capitol from Federal attack that Jackson’s supporters believed were imminent.[3]

Attempts were made to reconcile the two sides. A semi-formal truce was negotiated between General William S. Harney Commander of the Western Department of the U.S. Army and Missouri State Guard Major General Sterling Price. They agreed to maintain order in the parts of the state under the control of their various forces, protect the persons and property of all persons, and avoid actions which might excite conflict. Harney unofficially agreed to (generally) restrict Federal forces to metropolitan St. Louis. Price ordered that the mustering of Missouri State Guard volunteers in Jefferson City be halted. Instead, potential guardsmen were directed to muster with regional commanders in nine new Military Districts, the organizational course of action initially envisioned under the post-May 10 Military Bill.[4]

Harney understood that Price had would hold the state for the Union, and in fact, Price promised him that should Confederate forces enter Missouri, the MSG would fight alongside the U.S. Army to drive the Confederates out. At the same time however, representatives from Governor Jackson and Missouri’s Lt Governor, Thomas C. Reynolds were meeting with Confederate authorities asking them to send send an army into Missouri.[5] They promised Confederate President Jefferson Davis that the Missouri State Guard would cooperate with the Confederate Army to drive Federal forces from Missouri and “liberate” the state.

Missouri Unionists felt that Harney’s confidence in Governor Jackson and General Price was dangerously misplaced, and that Harney’s unilateral adherence to the “truce” was endangering the state. In a stream of letters and cables to the Lincoln government, they demanded Harney’s removal, and eventually on May 30, General Harney was superseded by (recently promoted) Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon.

Lyon, Jackson, and Price met one last time, on June 11, at the Planter’s House hotel in St. Louis. Jackson demanded that Federal forces remain isolated in St. Louis and that pro-Unionist Home Guard companies of Missouri Unionists around the state be disbanded. Jackson made a wide variety of promises, but all his position came down to: Federal abandonment of the state (outside St. Louis); disarmament of all Missouri Unionists (except those officially enlisted in the four regiments called for under Lincoln’s April militia call); and no meaningful verification. (Federal authorities would rely on Jackson’s and Price’s good will and assurances that they would hold the state for the Union.)

In the face of Jackson’s inflexible position, Lyon (according to Governor Jackson’s secretary) eventually stated that rather than allow Jackson to dictate to the federal Government he (Lyon) would “see you, and you, and you, and you, and every man, woman, and child in the state dead and buried.” Lyon concluded by turning to the Governor, and stating “This means war. In an hour one of my officers will call for you, and conduct you out of my lines.”[6]

Governor Jackson and General Price fled toward the capital at Jefferson City, arriving there on June 12. They ordered the bridges on the main rail lines burned. After quickly concluding that Jefferson City could not be held, Jackson and the State Guard departed for Boonville the next day. General Lyon promptly set out after them by steamboat, with two Federal volunteer regiments, a company of U.S. regulars and a battery of artillery—about 1,700 men in all. His goal was to seize the capital and disperse the State Guard.

Price hoped to buy enough time to consolidate State Guard units from Lexington and Boonville, though he planned to withdraw from Boonville if Lyon approached. State Guard Colonel John S. Marmaduke’s unit began organizing at Boonville, while Brig. Gen. Mosby M. Parsons was instructed to take up a position 20 miles (32 km) to the south in Tipton. At this juncture, Price left Boonville due to illness and joined the forces assembling at Lexington. This was unfortunate, as it left the governor—a politician—in charge. Instead of retreating, Jackson decided to make a stand, because he feared political fallout if he made another withdrawal. Many of his men were eager to face the enemy, but they were armed only with shotguns and hunting rifles, and lacked sufficient training to fight effectively at the time. Marmaduke was opposed to giving battle, but he reluctantly assumed command of the waiting state forces.

Lyon, meanwhile, had reached Jefferson City on June 15, learning that Jackson and Price had retreated towards Boonville. Leaving behind 300 troops of the 2nd Missouri Volunteers to secure the capital, Lyon resumed his pursuit of Price on June 16, landing about 8 miles (13 km) below Boonville on June 17. Informed of Lyon’s approach, Jackson attempted to call up Parsons’ command at Tipton, but it was unable to arrive in time.

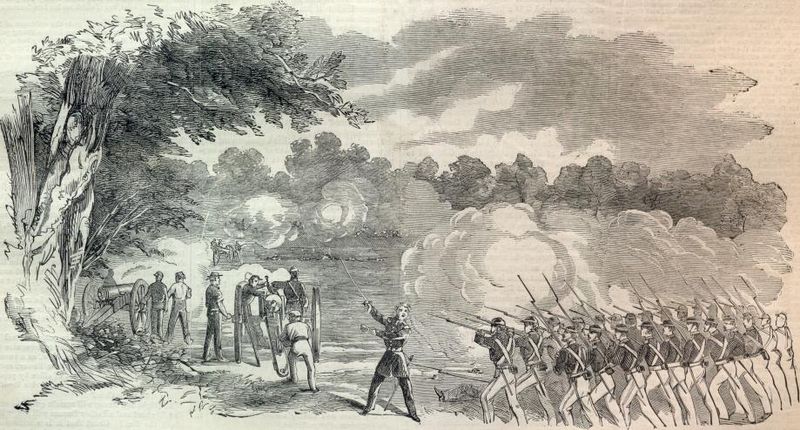

The battle itself was actually little more than a skirmish, but it was one of the first significant land actions of the war, and had grave consequences for Confederate hopes in Missouri.

After disembarking, Lyon’s troops marched along the Rocheport Road toward Boonville at around 7 am. Part of Marmaduke’s eager but ill-equipped State Guard force waited on a ridge behind the bluff, totalling about 500 men. They had no artillery support, since it was all with Parsons at Tipton. Inexplicably, Governor Jackson, observing from a mile or so away, held his only reasonably-disciplined and organized command the long established (St. Louis) Washington Blues militia company (usually known as “Captain Kelly’s Company”) in reserve; it would take no part in the battle.[7]

Lyon’s command encountered State Guard pickets as they approached the bluffs, but Lyon deployed skirmishers and continued to push his men forward rapidly. The Union artillery (Captain Totten’s battery, Company F, 2nd U.S. Lt Artillery) quickly displaced sharpshooters stationed in the William Adams house, while Union infantry closed with the line of guardsmen and fired several volleys into them, causing them to retreat. This portion of the fighting lasted barely 20 minutes. Some attempts were made to rally and resist the Federal advance, but these collapsed when a Union company flanked the Guard’s line, supported by cannon fire from a light howitzer on the river steamer Augustus McDowell. As Marmaduke feared, the Guard’s retreat rapidly turned into a rout. The guardsmen fled back through Camp Bacon and the town of Boonville; some continued on to their homes, while the rest retreated with the Governor to the southwest corner of Missouri. Lyon took possession of Boonville at 11 am.

The short fight at Boonville and the State Guard’s precipitate retreat earned the battle the nickname of “The Boonville Races.”

Federal casualties were light, with five men killed or mortally wounded and seven less seriously injured. There are no reliable figures of casualties for the Missouri State Guard: but it appears five were killed or mortally wounded and ten wounded, while about 60 to 80 were captured. Lyon seized the State Guard’s supplies and equipment, which included two iron 6-pounder cannon without ammunition, 500 obsolete flintlock muskets, 1200 pair of shoes, a few tents, and food.

The real impact of the Battle of Boonville was strategic, far out of proportion to the minimal loss of life. The Battle of Boonville effectively ejected the secessionist forces from the center of Missouri, and secured the state for the Union. Price realized he could not hold Lexington and retreated, though he would return three months later to re-take the city. Secessionist communications to the strongly pro-Confederate Missouri River valley were effectively cut, and would-be recruits from slave-owning regions north of the Missouri River found it difficult to join the Southern army. Provisions and supplies also could no longer be obtained from this section of the state.

A second result of the battle was demoralization. While the Missouri State Guard would fight and win on other days (most notably at Wilson’s Creek and Lexington just two and three months later, respectively), it was badly dispirited by this early defeat. Lyon’s victory gave the Union forces time to consolidate their hold on the state, while Marmaduke’s disappointment led him to resign from the Missouri State Guard and seek a regular commission in the Confederate Army. Marmaduke and Price would team up again during Price’s great Missouri Raid of 1864, culminating in their defeat at the Battle of Westport on October 23 of that year, which in turn put an end to significant Confederate operations in the state.

Following the battle of June 17, Boonville would serve as the scene for three other Civil War engagements, all of extremely minor importance:[8]

The Second Battle of Boonville was fought on September 13, 1861, when Colonel William Brown of the Missouri State Guard led 800 men in an attack on 140 pro-Union Boonville Home Guardsmen while the Union soldiers were eating breakfast. Due to rain, the Confederates wrapped their flags in black sheathing, which the Home Guard mistook as a sign of no quarter. Highly motivated by a perception that the fight was one of “victory or death”, the Home Guardsmen managed to defeat the State Guard troops, killing Colonel Brown in the process.

The Third Battle of Boonville was fought on October 11, 1863, during Shelby’s Great Raid, and saw General Joseph Shelby‘s troops engage Union forces in the city. When Federal reinforcements arrived the next day, the Confederates retreated westward.

The Fourth Battle of Boonville was fought on October 11, 1864 between Unionists and elements of General Sterling Price’s Army of Missouri, who had occupied the town. This skirmish resulted in a Confederate victory, though Price’s forces abandoned the city the following day.