About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Few ties are as strong as the military bands of brotherhood.

The Gist of the Matter

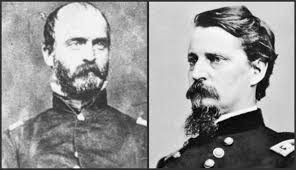

Two soldiers, close friends for years, had the unlikely distinction of meeting (sort of) for the last time at Gettysburg. One fought for the Union, one for the Confederacy. One died in battle. The other nearly became President of the United States.

Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (1824-1886) was a Pennsylvanian of a solid middle class background, named for a hero of the War of 1812. He had a West Point education (Class of 1844), graduating mid-class, assigned to the infantry, and then proving his soldierly mettle mostly as a quartermaster. In private life, he married Almira (Russell) in 1850, and had two children who predeceased him. He received various assignments and promotions and, once the Civil War began, he was made a Brigadier General in the infantry. During the Peninsula Campaign, General George McClellan telegraphed the War Department that “Hancock was superb today.” The nickname “Hancock the Superb” stuck.

Lewis Armistead

Although born in North Carolina, Lewis Armistead (1817-1863) came from a pedigreed First Family of Virginia background. Military service ran in his blood. His father and four uncles all served in the War of 1812. One uncle was commander at Fort McHenry, of Star-Spangled Banner fame. He went to West Point, but resigned midway – possibly for a disciplinary action, possibly academically – or possibly both. Notwithstanding, his influential family arranged for him to receive a commission as Second Lieutenant in the Regular Army about the same time he was expected to graduate. Nicknamed “Lo” for “Lothario,” he married twice. Both wives died young. Two of his three children died before they were five.

The War With Mexico

Many historians today consider the War with Mexico (1846-48) the precursor to the American Civil War. It thrust West Point classmates and alumni (or even dropouts) together, tempering in battle the talents that presaged the Civil War fifteen years later. They were all American soldiers then. Some bonds of camaraderie could withstand the strains that would follow.

Hancock and Armistead found themselves serving together in Mexico. They fought bravely, intelligently and honorably, were decorated for valor, and earned brevet (on-the-field) promotions. They also became lifelong friends, and remained close despite a decade of varying paths in their respective careers. When Lo Armistead tragically lost his wives and children, it was Hancock who came to his side.

California

Gold was discovered in California in 1848 and ignited a mad rush to that far-away place for the riches everyone hoped to find. Naturally law and order had to be preserved, and by 1858-9, the two mid-range officers and friends, Hancock and Armistead, found themselves reunited in Southern California. Now in their late thirties, they were tempered by the personal and professional challenges life throws at everyone.

Their friendship which had always remained strong, now became cemented in California. The bond deepened to a point that they both considered themselves “close as brothers.”

Both men considered themselves Democrats as well, but not overly “political.” Both, however, were solidly for the “union,” whose uniform they had proudly worn for more than a decade.

As the country drifted into the chasm that would pull it apart, discussions obviously abounded about the choices they had to make. Winfield Scott Hancock was not openly hostile to the South and replied simply, “I shall not fight upon the principle of state-rights, but for the Union, whole and undivided.” He returned East to join the Union Army, where his experience, seniority and fine record quickly earned him promotions.

For Lewis Armistead, when Virginia seceded in May, 1861, his choice was painful but easy. Virginia was his country. He too was quickly promoted, but in the Army of Northern Virginia.

It is said in family lore and in apocryphal lore, that there was a farewell party the night the soldiers left California to go “home.” It is generally believed that Lo Armistead, considered a stern man personally, put his hand on Hancock’s shoulder and, in tears, told him, “Hancock, goodbye; you can never know what this has cost me and I hope God will strike me dead if I am ever induced to leave my native soil, should worse come to worse.” According to Pulitzer Prize winning author Michael Shaara in The Killer Angels, Armistead made a vow that God should strike him dead if he ever lifts his hand against Hancock. Either way, according to a memoir written years later by Almira Hancock, it was a very rough parting between the two men who had been so close for seventeen years.

Gettysburg and Afterwards

Lo Armistead was a Brigadier General in Pickett’s Division at the time of Gettysburg. Win Hancock was a Brigadier General in command of the Union’s center.

Fact and lore coincide on Pickett’s Charge on the third day of battle. Always brave and disciplined, Armistead skewered his hat with his sword, raised it high, and rallied his men, shouting, “Virginians! With me! Who will come with me?”

He made it all the way across that huge unprotected battlefield where it rained artillery shells and hundreds lay dead and dying, and reached the stone wall before he was wounded. Lore says he asked to be taken to General Hancock, but was told the General had been wounded an hour earlier. They never saw each other again. The facts and the sentiment are generally true.

Armistead’s wounds were not believed to be mortal, and the doctors expected his recovery. But he died from infection two days later, leaving his gold watch and other prized possessions to his dearest friend.

Hancock’s wounds were not mortal, but they were serious and lingering. After his basic convalescence, he returned to the field, and despite great pain, commanded his division at Petersburg.

After the war, he was promoted to Major General, remained in the US Army, and developed political ambitions. In 1880, he was the Democratic nominee for President. He lost the election to James A. Garfield by less than 40,000 votes out of 9 million cast.

Hancock, Almira Russell – Reminiscences of Winfield Scott Hancock – HardPress Publishing (reprint) 2013

Shaara, Michael – The Killer Angels – Mass Market Paperback, 1987