About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

On March 10, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln appointed Ulysses S. Grant as General-in-Chief of the Armies of the United States. Grant brought with him, from his successes in the Western Theater of the war, a reputation for the doggedness that Lincoln was seeking in his generals. Unlike other Union generals, Grant was tenacious.

Upon his arrival in Washington, Grant drafted a plan to get the various Union armies in the field to act in concert. He also devised his Overland Campaign to invade east-central Virginia. Unlike previous campaigns into that area, Grant’s plan focused upon defeating General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia rather than capturing or occupying geographic locations. Grant instructed General George Meade, who commanded the Army of the Potomac, “Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also.” Grant realized that, with the superior resources he had at his disposal, Lee would lose a war of attrition, as long as Northern troops persistently engaged the Confederates.

On May 4, 1864, Grant launched his Overland Campaign when the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers, occupying an area locally known as the Wilderness. For the next eight weeks, the two sides engaged in a series of horrific battles that produced unprecedented numbers of casualties. Following a bloody frontal assault at Cold Harbor that cost the Federals roughly 13,000 casualties, Grant abandoned his hope to defeat Lee’s army head-on. Instead, Grant aimed to isolate the Army of Northern Virginia at Richmond and slowly starve it into submission by cutting off its supply lines. The key to the plan was capturing Petersburg, Virginia.

Petersburg, Virginia, sits on the south bank of the Appomattox River, approximately twenty miles south of Richmond. During the Civil War, the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad was an important conduit for supplies to the Confederate capital. Besides the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad, two other rail lines converged at Petersburg. The Weldon Railroad (also called the Petersburg and Weldon Railroad) connected Petersburg to the Confederacy’s last linkage to overseas markets at Wilmington, North Carolina. Farther to the west, the South Side Railroad joined Petersburg to Lynchburg, Virginia, and points westward. If Grant could cut the rail lines, it would force Lee to abandon Richmond.

Although Grant’s focus during the summer and fall of 1864 was on cutting off supply routes into Petersburg, he also launched several assaults north of the James River against Richmond. Grant recognized that forcing Lee to defend two fronts would thin the Confederate defenses around Petersburg, enhancing Union expectations for success. At the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm and New Market (September 29-30, 1864) federal soldiers captured Fort Harrison and other portions of Richmond’s outer defenses along Darbytown and New Market Roads.

Darbytown and New Market Roads run roughly parallel to each other into Richmond from the southeast. The federals anchored the right flank of their lines outside Richmond at Darbytown Road, several miles north of New Market Road. Attempting to regain the ground lost at the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm and New Market Road (September 29-30, 1864), Lee ordered an offensive against the newly extended federal lines one week later.

On October 7, 1864, two Confederate divisions turned the Union right flank and forced the Yankees defending Darbytown Road to retreat south to the safety of the federal earthworks at New Market Road. Later that day, the Yankees entrenched at New Market Road repulsed a second Confederate assault, forcing the Rebels to retreat to the Richmond defenses.

Determined to re-secure the area they had abandoned outside of the Confederate capital, Lee ordered Major. General Charles Field and Major General Robert Hoke to build a new line between the Federals and Richmond’s inner defenses. The work began on October 11. The next morning, Union pickets observed the construction activity and reported it up the line through Major General August V. Kautz to Major General Benjamin Butler to Grant.

Upon learning of Lee’s efforts to create new breastworks outside of Richmond, that afternoon Grant ordered Butler to drive the Rebels away from the new works. Butler selected the 1st and 3rd divisions of Major General Alfred Terry’s 10th Corps for the mission. Butler advised Terry to expect to encounter up to 6,000 Confederates and that Kautz’s cavalry would support him. Concerned that his infantry totaled only 4,700 soldiers, Terry requested more men, but Butler refused.

Terry’s soldiers moved forward at 4 a.m. on October 13, for an attack on the enemy lines scheduled for dawn. When Kautz’s late arrival delayed the assault, however, the Federals spent the next few hours completing reconnaissance and organizing battle lines.

While Terry conducted his surveillance, Lee strengthened his left after learning the Yankees were attempting to flank him. At 10:30 a.m., Terry advised Butler, “As at present advised, I think we cannot pierce their works except by massing on some point and attacking in column. I hesitate to do this without further instructions from you after our conversation of last night. Please direct me in regard to it.”

At 12:10 p.m., Butler directed Terry to remain in position until he could consult with Grant. Upon being apprised of the situation, Grant cautioned Butler that “I would not attack the enemy in his intrenchments.” Before Grant’s recommendation reached the field, however, Kautz reported to Terry that he had found an opening in the Confederate line that he believed he could exploit. Despite his misgivings, Terry ordered his men to move against the Rebels.

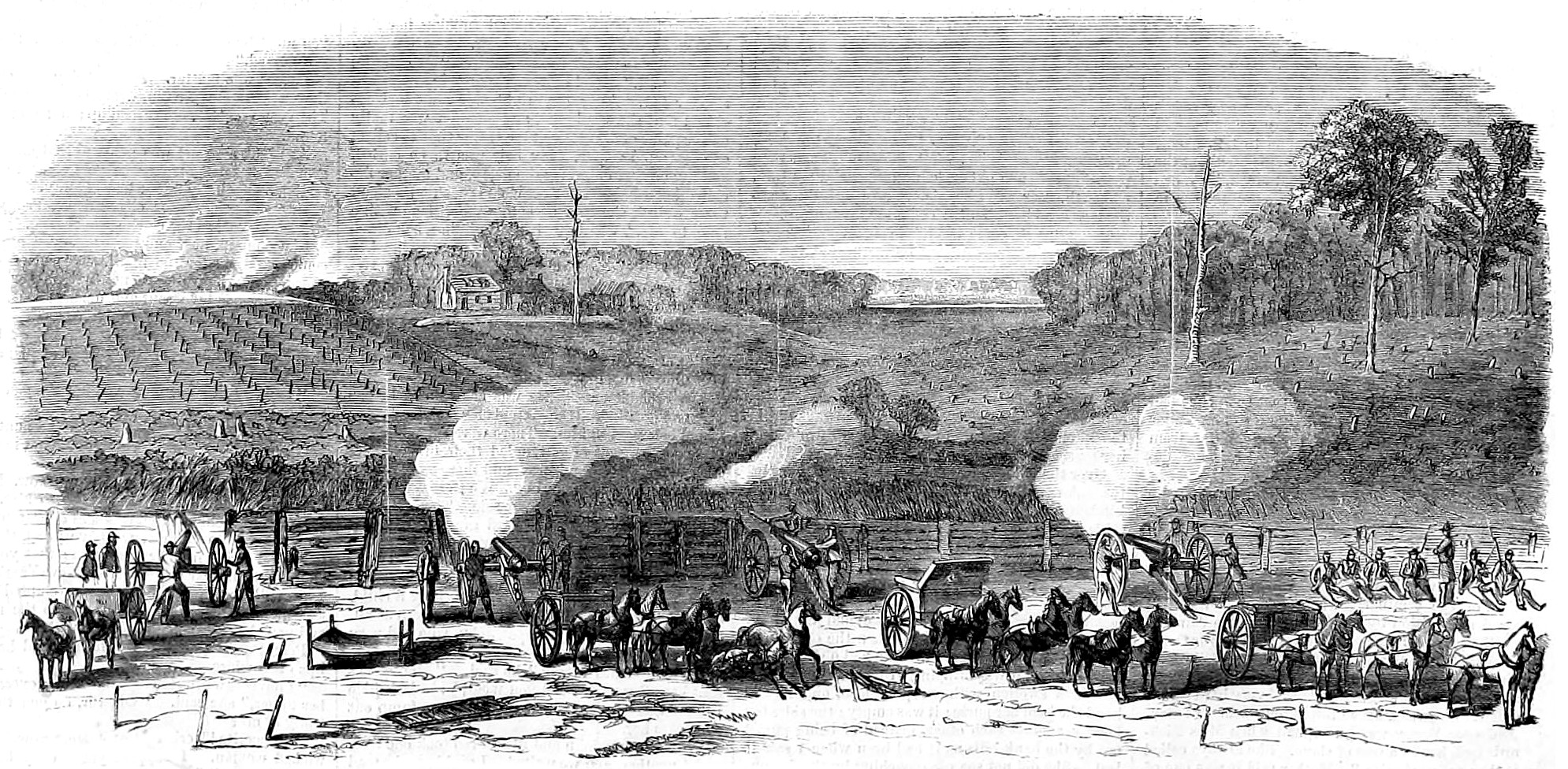

Shortly before 2 p.m., the Bluecoats attacked a Rebel position approximately one-half mile south of Charles City Road. The Confederate infantry caught the Federals in a crossfire while they raked them with artillery fire. Some of the strike force, which included men from the 10th Connecticut, 62nd Ohio, 39th Illinois and 67th Ohio, reached the Rebel breastworks before being repulsed. By 3 p.m., the assault was a disaster, and Terry ordered a retreat. The Confederates pursued until federal artillery fire drove them back. By 6 p.m. the battle was over, and Terry’s men had returned to their lines.

Although the Rebels lost about 513 soldiers compared to 437 Union casualties (thirty-six killed, 358 wounded, and forty-three captured), the Battle of Darbytown Road was a Confederate victory. The Federals failed in their attempt to prevent Lee from constructing new defenses east of Richmond.