About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Events leading to the Battle of New Market Heights began during the blistering summer of 1864, when overall Federal commander Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant directed the Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, to relentlessly push the Confederates south from the Rappahannock River toward the Appomattox River. To counter that strategy and stop the Union drive, General Robert E. Lee put his undermanned Army of Northern Virginia into a complex array of trench lines and fortified strongpoints defending Richmond and its supply routes running through Petersburg.

In addition to watching Grant’s powerful army, Lee also had to keep a wary eye on the Army of the James, a force of 35,000 men in the XVIII and X corps and a cavalry division, entrenched in and around Williamsburg, Va. Commanded by the militarily inept but politically well-connected Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, that army boasted the largest contingent of black troops of any Union force. Butler had used his political influence to get appointed commander of the Department of Virginia and North Carolina, and then made himself commander of the Army of the James.

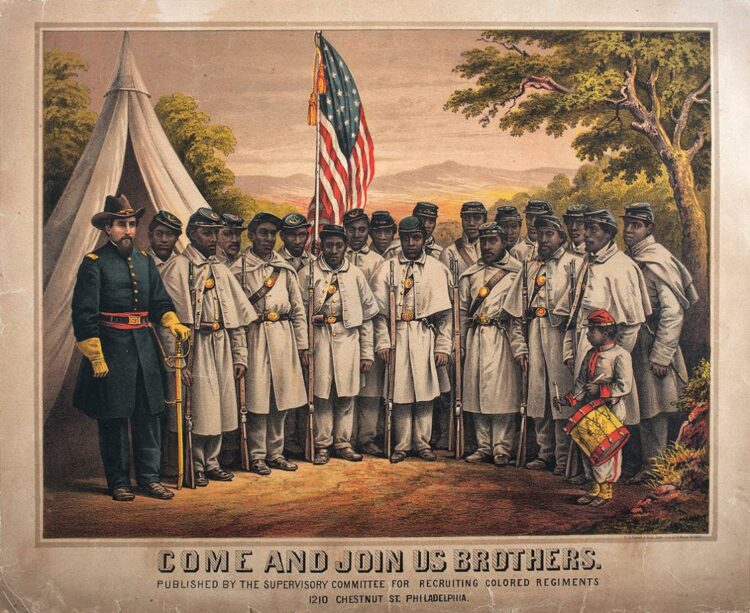

During the winter of 1863-64, Butler sent raiding parties beyond his fortified lines to find black recruits to bolster the ranks of his regiments of U.S. Colored Troops (USCT). General Order 46, issued December 5, 1863, made his position clear: “The recruitment of colored troops has become the settled purpose of the Government….It is the duty of every officer and soldier to aid in this recruiting, irrespective of personal predilection.”

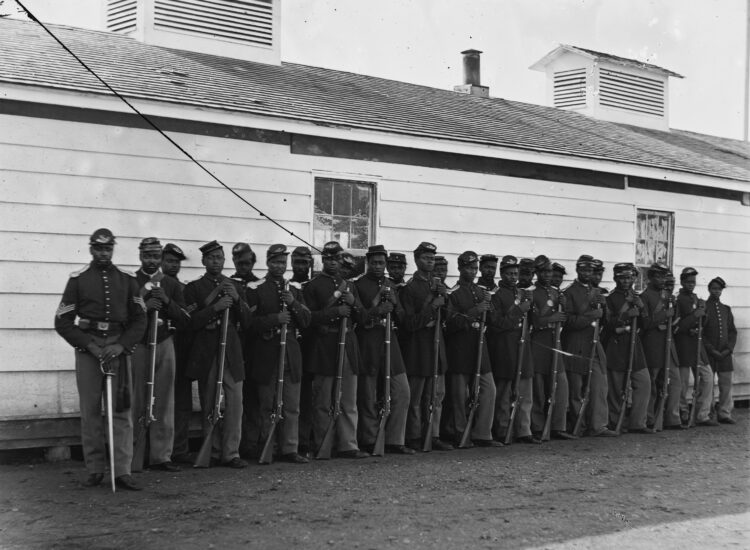

Though black troops had been permitted to join the Union Army, they were not allowed to gain commissions and were led by white officers. Black units were also placed in their own brigades. In the Army of the James, black troops made up Brig. Gen. William Birney’s Colored Brigade of the X Corps. Brigadier General Charles J. Paine’s 3rd Division of the XVIII Corps was made up of three all-USCT brigades: the 1st Brigade led by Colonel John Holman, the 2nd Brigade commanded by Colonel Alonzo G. Draper and Colonel Samuel Duncan’s 3rd Brigade.

Early in May 1864, Butler moved his integrated army up to the vicinity of Bermuda Hundred on the James River. He fortified and then made several tentative and unsuccessful attempts to breach the Richmond defenses. On May 16, an assault by Confederate forces under General P.G.T. Beauregard forced Butler back into his trenches. Grant caustically described Butler’s army ‘as completely shut off from further operations against Richmond as if it had been in a bottle tightly corked.’

With Butler temporarily neutralized, Grant ordered the Army of the Potomac out of its trench lines at Cold Harbor on the night of June 12, marching 100,000 men almost 50 miles over rough and swampy terrain to the south side of the James River. With a presidential election only a few months away, Grant wanted a decisive victory to bolster the spirits of the war-weary North. Instead, he found himself in the frustrating siege of Petersburg.

Repulsed at every turn by the resourceful Lee, he finally listened to a complex plan proposed by General Butler on September 20 that Grant hoped would draw Lee’s attention and force him to redeploy troops north of the James, allowing the Army of the Potomac to launch a coordinated attack against the South Side Railroad, a critical supply line into Petersburg. And if Butler succeeded in capturing Richmond, Grant reasoned, so much the better.

Early on the evening of September 28, Butler called a council of war to give his commanders, Maj. Gen. David Birney of the X Corps, Maj. Gen. Edward O.C. Ord of the XVIII Corps and Cavalry Division commander Brig. Gen. August V. Kautz, the details of the operation. In Butler’s mind, the primary objective remained the capture of Richmond, not drawing forces away from Petersburg.

The plan called for two divisions of Ord’s XVIII Corps, on the left wing, to make a surprise crossing of the James at Aiken’s Landing (after building a pontoon bridge across the river in the pre-dawn hours before the attack) and move up the Varnia Road to capture Confederate Fort Harrison. Ord’s forces would then wheel west and destroy the Confederate bridges at and above Chaffin’s Bluff, and race up the Osborn Turnpike for Richmond.

At precisely the same time, on the right wing, Birney’s X Corps, plus Paine’s USCT regiments detailed from the XVIII Corps, would cross the James River, advance from Deep Bottom, carry New Market Heights and strike out for Richmond on the New Market Road. Finally, Kautz’s cavalry would move to the Darbytown Road and, when New Market Heights was cleared, ride hard for the Confederate capital.

Paine’s black soldiers were to spearhead the attack on New Market Heights because Butler, as he put it, ‘wanted to convince myself whether the negro troops will fight, and whether I can take, with the negroes’ a stronghold that had denied previous Union attack. Butler had been an early advocate for arming black men, and had done so when he was overseeing the occupation of New Orleans in 1862.

Butler was mindful of the July disaster at the Crater, where black troops had been poorly led — really not led at all — by a drunken commander, and he developed copious instructions for his plan and the proposed attack, some 16 pages worth of material. Butler briefed his generals, and the plan was put in motion. Throughout the night and into the pre-dawn hours of September 29, the narrow roads and meandering country lanes of Henrico County shuddered under the steady tread of thousands of marching men. Some units were on the move even before Butler outlined the final details of his plan to his corps commanders.

The X Corps was scheduled to arrive at Bermuda Hundred a full day before the attack in order to give it sufficient rest. But General Birney misunderstood the original order to move out, and the X Corps did not begin arriving at the rendezvous point until 2 a.m. on September 29. Tired, hungry and understrength because of stragglers, the X Corps, including the accompanying XVIII Corps USCT men detailed to storm the earthworks at New Market Heights, would be going into battle with no hot food and almost no rest.

Butler always anticipated that his attacks would catch the Confederates unaware. But the movements of so many men could hardly be kept secret, and by 4 a.m., the Rebel defenders of New Market Heights were already under arms and having a hot breakfast, awaiting the arrival of the Union attackers. The multilayered breastworks, fronted by a double line of abatis, held Brig. Gen. John Gregg’s 2,000 veterans, five infantry regiments from the famous Texas Brigade led by Colonel Frederick Bass, dismounted cavalry from Virginia and South Carolina under Brig. Gen. Martin Gary, and cannoneers of the Rockbridge Artillery and Richmond Howitzers.

While the Confederates breakfasted, Union officers quietly moved through the darkness and ordered the exhausted men to wake up and stand to arms. Christian Fleetwood, a sergeant major in the 4th USCT, noted in his diary: ‘Regimental papers and knapsacks…packed away. Coffee boiled and line formed.’

New Market Heights, with its signal tower and batteries of artillery at each end, loomed ahead. Butler expected General Birney to have almost 16,000 troops for the attack, including Paine’s 3,800 USCT men, but because of the late arrival of much of the X Corps and significant straggling on route, Birney could count on only 10,300 effectives. Nevertheless, Birney formed up the X Corps in three columns. He planned to attack the Confederate defenses at New Market Heights with only one of them, Paine’s 3rd Division of USCT. One of the two remaining columns would be held in reserve; the other would pin down potential Confederate reinforcements and await orders before joining the assault.

Butler rode through the USCT ranks, urging the men to charge the enemy with the words ‘Remember Fort Pillow’ on their lips. The first wave of attackers would be advancing without percussion caps on the locks of their rifles because Butler believed that would prevent the troops from pausing to fire and reload. He wanted to avoid confusion among the mostly untested soldiers and allow the officers issuing orders to be heard.

The men of the USCT shouldered their muskets, smartly formed ranks and passed through the defenses of Deep Bottom, heading north through the fog-shrouded pre-dawn darkness. Around 5:30 a.m., the crackling of musket fire announced that skirmishers of the 22nd USCT, part of Holman’s brigade, had opened the engagement by driving back the advance pickets posted by Gregg above the Kingsland Road.

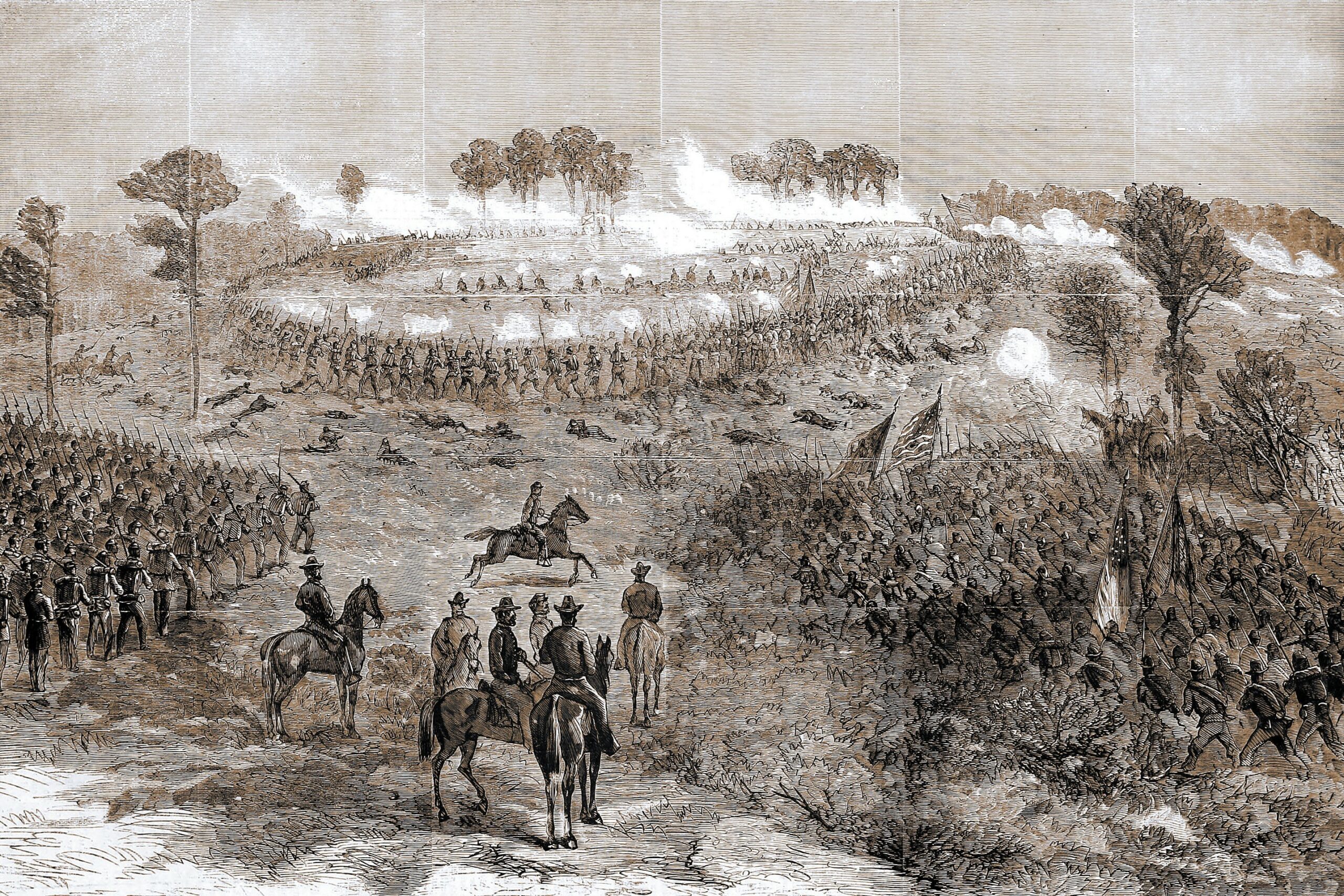

The soldiers of Duncan’s small brigade of the 4th and 6th USCT that followed had no way of knowing that most of the other units of Paine’s division that were to be in the attack had been delayed by swampy terrain, so they were spearheading the attack on their own. The geography of the battlefield would continue to work against the attacking troops. To reach the Confederate earthworks, the USCT soldiers had to cross about 500 yards of a rising plain. Across this plain ran Four Mile Creek, creating a marshy but not impassible swamp. Beyond the creek lay a deep, heavily wooded ravine that ran parallel to the New Market Road. Beyond the ravine another open plain of about 300 yards sloped northward toward the road and the Confederate breastworks.

As the sun slowly burned through the dense ground fog, the long blue lines of the 4th and 6th USCT began to emerge from the mists. The Confederate defenders put down their coffee, picked up their rifles and — peering into the gray half-light of dawn — searched for their targets. With no covering artillery barrage, the Battle of New Market Heights opened like a shadow play upon a mostly silent stage. Duncan’s two regiments deployed in a skirmish line about 200 yards long, the 4th leading and the 6th echeloned to the left rear. He described his men disappearing ‘as they entered the fog that enwrapped them like the mantle of death.’

The Confederates continued to hold their fire as the Federals crossed the open field, stumbled through the wooded ravine and splashed through the marshes of Four Mile Creek. Word raced through the Confederate ranks that black troops were attacking. Pickets shouted, ‘Niggers, boys, niggers,’ as they tumbled into the earthworks. Without waiting for orders, reinforcements from up and down the line quickly came to the aid of their comrades.

The USCT soldiers pressed on to a line of chevaux-de-frise, implanted logs drilled with holes holding a crisscross of sharpened wooden stakes. Many of the men dropped to the ground, hesitant to make a final push to the breastworks. With most of the officers dead or wounded, the sergeants of the 4th USCT assumed leadership. After the battle, Fleetwood described the carnage in his diary: ‘When the charge was started, our Color guard was full; two sergeants and ten corporals. Only one of the twelve came off that field on his own feet. Most of them are there still….It was a deadly hailstorm of bullets sweeping men down as hail-stones sweep the leaves from trees….It was very evident that there was too much work cut out for our two regiments….We struggled through two lines of abatis, a few getting through the palisades, but it was sheer madness….’

As the 4th USCT became entangled in the first line of abatis, the morning calm exploded when Bass’ veteran gunmen opened fire. Caught in the open, the 4th USCT was blown apart in a matter of minutes. Color bearers and officers made easy targets for the defenders.

The valiant attackers’ meager foothold lasted only moments. Bass’ Texans swarmed out of the earthworks and pounced upon their adversaries. Most of the attackers were killed outright, but some were briefly taken prisoner. Confederate accounts differ about what happened to the captured black soldiers. Some reports indicate that the captives and some of the wounded were quickly shot. Other accounts indicate that the black troopers were offered the choice of Libby Prison or becoming regimental servants.

With Duncan felled by four wounds, command passed to Colonel John W. Ames of the 6th USCT. Instead of supporting the 4th USCT, the men of the 6th launched their own attack. It fared no better than the previous onslaught. With the two regiments shot to pieces, Ames began a withdrawal. The entire action had taken about 40 minutes. With the sun barely up, the Confederate firestorm had effectively destroyed Duncan’s brigade as a fighting unit.

Unwilling to accept failure, Birney and Paine chose to repeat the unsuccessful tactics, this time using Draper’s 1,300-man 2nd Brigade. At about 7 a.m., Draper’s regiments, the 5th, 36th and 38th USCT, dutifully moved out.

But unlike Duncan, Draper aligned his regiments into a column, with the 5th USCT leading, followed by the 36th and 38th. Instead of presenting a long line of targets, Draper’s front was only six companies wide and 10 ranks deep.

It didn’t make any difference, however. Draper’s attackers marched into another devastating blast of musket and artillery fire from the Confederate position. Like Duncan’s men before them, the brave black troopers hacked their way through the obstacles and struggled toward the earthworks. And like Duncan’s company sergeants before them, Draper’s sergeants took up the colors and rallied their men when their officers were killed or wounded.

Draper’s is the only official after-action report filed by any Union officer in the Official Records. Submitted on October 6 while he recuperated from his wounds, it describes the second assault developing much like the first one: ‘After passing about 300 yards through young pines, always under fire, we emerged upon the open plain about 800 yards from the enemy’s works….Within twenty or thirty yards of the rebel line we found a swamp which broke the charge….Our men were falling by the scores. All the officers were striving constantly to get the men forward.’

The efforts of the white officers and black noncoms yielded success. After withstanding withering fire for what Draper called ‘a half hour of terrible suspense,’ the Confederate fire seemed to slacken. Draper’s men swept up the remnants of the 4th and 6th USCT, and the determined attackers surged forward into the Confederate positions.

Sergeants James H. Harris and Edward Ratcliff, Private William Barnes and 36th USCT Private James Gardiner were among the first to enter the Confederate trenches. Gardiner shot and bayoneted a Confederate officer trying to rally his men on the ramparts.

Corporal Miles James of the 36th lost the use of his left arm (it was later amputated) but continued firing at the enemy with his right. Barnes and Harris each suffered multiple wounds but refused to leave the field.

While it does not detract from the heroism of Duncan’s and Draper’s regiments, New Market Heights was in fact virtually abandoned, defended only by a small rear guard, by the time the attacking Union forces spilled into the Confederate trench lines. Nonetheless, J.D. Pickens of the Texas Brigade acknowledged the fighting qualities of their attackers, writing, ‘I want to say in this connection that, in my opinion, no troops up to that time had fought us with move bravery than did those Negroes.’

Gregg had indeed ordered his men to redeploy and reinforce Confederate defenses along the Varnia Road between Forts Harrison and Gilmer. But instead of going directly to the aid of Fort Harrison, which eventually fell to Ord’s XVIII Corps, the Texas Brigade and the dismounted cavalry units took up positions along the Confederates’ intermediate line of defense.

If questions persist about how New Market Heights fell, there has never been any debate about the devastating losses suffered by its attackers. The actual fighting lasted only about 80 minutes, and when it was over around 8 a.m., Duncan’s brigade had suffered 68 killed, almost 300 wounded and 22 missing. Draper’s brigade sustained 63 dead, 366 wounded and 23 missing. And for some of the men of Draper’s brigade, the day’s slaughter was not yet over. For reasons never adequately explained, Paine ordered the battered remnants of the 5th USCT to withdraw from New Market Heights and move to support the attack on Fort Gilmer. The regiment suffered another 100 casualties in that ultimately unsuccessful action.

Butler’s report to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton four days after the battle in part read: ‘My colored troops under General Paine…carried intrenchments at the point of a bayonet….It was most gallantly done, with most severe loss. Their praises are in the mouth of every officer in this army. Treated fairly and disciplined, they have fought most heroically.’ Butler had his answer as to whether black men could fight.

Northern correspondents were also captivated by the role of the USCT, focusing on their bravery and, to Butler’s undoubted relief, generally ignoring the fact the attacks fell short of their goal of capturing Richmond. The New Market Heights dispatch of the New York Herald’s Thomas M. Look clearly shows how the fog of battle reveals only part of what really transpires on the killing ground: ‘Their charge in the face of the obstacles interposing was one of the grand features of the day’s operation….They never halted or faltered, though their ranks were sadly thinned by the charge, and the slashing was filled with the slain and wounded of their number.’

Veteran correspondent Henry Jacob Wisner of The New York Times echoed the sentiment of many observers when he wrote, ‘it was a wonderful, a sublime sight to see those black men stand up to the rack….’

Thomas Morris Chester, a black reporter for the Philadelphia Press, filed an October 5 dispatch from ‘a mere 5 1/2 miles from Richmond.’ In it, he declared that Paine’s division ‘had covered itself with glory, and wiped out effectively the imputation against the fighting qualities of colored troops.’ He amplified his conviction two weeks later: ‘One thing is certain, that the colored troops who compose this division…convinced the most skeptical that Negroes will not only fight, but do it desperately….’

Confederates saw things in a different light. The Richmond Examiner opined that ‘the country will be surprised that so much noise had been made and so little damage done.’ On October 14, Columbia’s Daily South Carolinian carried a letter stating, ‘Birney’s whole corps came against the position held by General Gary’s brigade, and was so severely handled that, when the order came for us to fall back, it permitted our thin line, though at close quarters at the time, to retire in order and without injury.’

Butler wanted more than mere words to herald the sacrifices made by his black soldiers. Only two avenues were open to him. One was promotion in rank, and the other was to award a medal authorized by Congress in 1862 for bravery on the battlefield, the Medal of Honor. Privates Barnes, Gardiner and Veal, along with Corporal James, were quickly promoted to sergeants. But there were no promotions for the 10 men who were already sergeants. The surviving white officers of the 4th USCT petitioned the War Department to authorize lieutenant’s bars for Sgt. Maj. Fleetwood, but their request was denied. Butler tried to promote Sergeant Milton M. Holland of the 5th USCT to captain, but the War Department refused to issue the commission.

With avenues of promotion shut down, that left the Medal of Honor. The award had not yet acquired the lofty status it holds today, and the criteria necessary for recognition were very different from modern standards. During the Civil War, 1,520 men and one woman received the Medal of Honor, but only 16 black soldiers and five black sailors earned the award.

Before the Medal of Honor could be awarded, recommendations from surviving regimental officers had to first go to division headquarters and then to Butler and a team of his subordinates. They sifted and winnowed the names and forwarded those remaining on the list to General Grant, where they were further reviewed and then sent to the War Department.

For months, no word came from Washington. Finally, on April 6, 1865, the War Department bestowed the Medal of Honor on 14 black veterans of New Market Heights. The recipients, except for Sergeant Alfred Hilton who died in a hospital on October 21, 1864, continued to serve with their regiments until the war ended. Sergeants Powhatan Beatty of the 5th USCT and Fleetwood and Alexander Kelly of the 6th USCT helped capture Fort Fisher in 1865. Sergeant Miles James of the 36th USCT asked to remain on active duty in spite of losing his arm, and was permitted to serve with the regimental provost guard. James marched with his company into Richmond on April 3, 1865, making him the only recipient of the Medal of Honor to reach the objective for which he and his comrades had sacrificed so much.

Sergeant Majors Milton M. Holland, of the 5th, and Fleetwood witnessed the surrender of General Joseph E. Johnston at Durham Station, N.C., on April 26, 1865. Almost 35 years later to the day, on April 25, 1898, Fleetwood offered his services to raise and equip a volunteer company of black soldiers and officers to fight in Cuba. The government never responded to his offer. Fleetwood died on September 28, 1914. His daughter, Edith, presented Fleetwood’s Medal of Honor to the Smithsonian Institution in 1948.

Holland later founded the Alpha Insurance Company, one of nation’s first black-owned insurance firms, and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Sergeant James Harris of the 38th USCT, who died on January 28, 1898, would also receive the Medal of Honor and be buried in the hallowed ground of Arlington.

Sergeant Robert Pinn of the 5th returned to his home in Stark County, Ohio, and opened a contracting business. Later he attended Oberlin College, studied law and, after being admitted to the bar, served as a U.S. pension attorney. He was active in the Grand Army of the Republic until his death on January 1, 1911. The historical record for the remaining Medal of Honor men is sparse. But when Beatty, the first of the Medal of Honor recipients to enlist and the last to die, was buried on December 16, 1916, a unique chapter in the history of black Americans in the Civil War ended.