About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

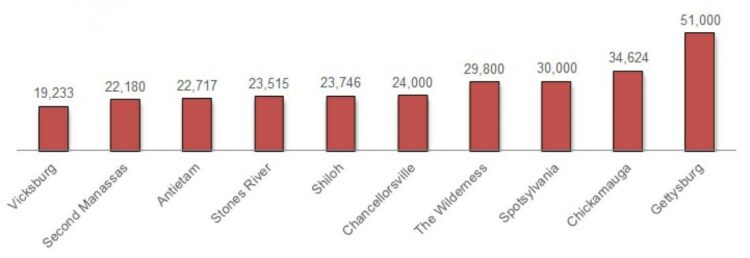

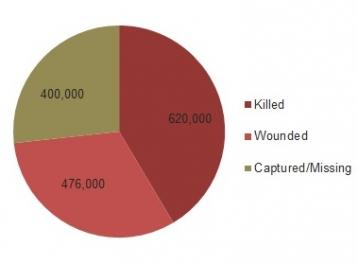

The Civil War was America’s bloodiest conflict. The unprecedented violence of battles such as Shiloh, Antietam, Stones River, and Gettysburg shocked citizens and international observers alike. Nearly as many men died in captivity during the Civil War as were killed in the whole of the Vietnam War. Hundreds of thousands died of disease. Roughly 2% of the population, an estimated 620,000 men, lost their lives in the line of duty. Taken as a percentage of today’s population, the toll would have risen as high as 6 million souls.

The human cost of the Civil War was beyond anybody’s expectations. The young nation experienced bloodshed of a magnitude that has not been equaled since by any other American conflict.

The numbers of Civil War dead were not equaled by the combined toll of other American conflicts until the War in Vietnam. Some believe the number is as high as 850,000. The Civil War Trust does not agree with this claim.

New military technology combined with old-fashioned tactical doctrine to produce a scale of battle casualties unprecedented in American history.

Even with close to total conscription, the South could not match the North’s numerical strength. Southerners also stood a significantly greater chance of being killed, wounded, or captured.

This chart and the one below are based on research done by Provost Marshal General James Fry in 1866. His estimates for Southern states were based on Confederate muster rolls–many of which were destroyed before he began his study–and many historians have disputed the results. The estimates for Virginia, North Carolina, Alabama, South Carolina, and Arkansas have been updated to reflect more recent scholarship.

Given the relatively complete preservation of Northern records, Fry’s examination of Union deaths is far more accurate than his work in the South. Note the mortal threat that soldiers faced from disease.

A “casualty” is a military person lost through death, wounds, injury, sickness, internment, capture, or through being missing in action. “Casualty” and “fatality” are not interchangeable terms–death is only one of the ways that a soldier can become a casualty. In practice, officers would usually be responsible for recording casualties that occurred within their commands. If a soldier was unable to perform basic duties due to one of the above conditions, the soldier would be considered a casualty. This means that one soldier could be marked as a casualty several times throughout the course of the war.

Most casualties and deaths in the Civil War were the result of non-combat-related disease. For every three soldiers killed in battle, five more died of disease. The primitive nature of Civil War medicine, both in its intellectual underpinnings and in its practice in the armies, meant that many wounds and illnesses were unnecessarily fatal.

Our modern conception of casualties includes those who have been psychologically damaged by warfare. This distinction did not exist during the Civil War. Soldiers suffering from what we would now recognize as post-traumatic stress disorder were uncatalogued and uncared for.

Approximately one in four soldiers that went to war never returned home. At the outset of the war, neither army had mechanisms in place to handle the amount of death that the nation was about to experience. There were no national cemeteries, no burial details, and no messengers of loss. The largest human catastrophe in American history, the Civil War forced the young nation to confront death and destruction in a way that has not been equaled before or since.

Recruitment was highly localized throughout the war. Regiments of approximately one thousand men, the building block of the armies, would often be raised from the population of a few adjacent counties. Soldiers went to war with their neighbors and their kin. The nature of recruitment meant that a battlefield disaster could wreak havoc on the home community.

The 26th North Carolina, hailing from seven counties in the western part of the state, suffered 714 casualties out of 800 men during the Battle of Gettysburg. The 24th Michigan squared off against the 26th North Carolina at Gettysburg and lost 362 out of 496 men. Nearly the entire student body of Ole Miss–135 out 139–enlisted in Company A of the 11th Mississippi. Company A, also known as the “University Greys” suffered 100% casualties in Pickett’s Charge. Eighteen members of the Christian family of Christianburg, Virginia were killed during the war. It is estimated that one in three Southern households lost at least one family member.

One in thirteen surviving Civil War soldiers returned home missing one or more limbs. Pre-war jobs on farms or in factories became impossible or nearly so. This led to a rise in awareness of veterans’ needs as well as increased responsibility and social power for women. For many, however, there was no solution. Tens of thousands of families slipped into destitution.

Compiling casualty figures for Civil War soldiers is a complex process. Indeed, it is so complex that even 150 years later no one has, and perhaps no one will, assemble a specific, accurate set of numbers, especially on the Confederate side.

A true accounting of the number of men in the armies can be approached through a review of three primary documents: enlistment rolls, muster rolls, and casualty lists. Following any of these investigative methods one will encounter countless flaws and inconsistencies–the records in question are little sheets of paper generated and compiled 150 years ago by human beings in one of the most stressful and confusing environments to ever exist. Enlistment stations were set up in towns and cities across the country, but for the most part only those stations in major northern cities can be relied upon to have preserved records. Confederate enlistment rolls are virtually non-existent.

Muster rolls, generated every few months by commanding officers, list soldiers in their respective units as “present” or “absent.” This gives a kind of snapshot of the unit’s composition in a specific time and place. Overlooking the common misspelling of names and general lack of specificity concerning the condition of a “present” or “absent” soldier, muster rolls provide a valuable look into the past. Unfortunately, these little pieces of paper were usually transported by mule in the rear of a fighting army. Their preservation was adversely affected by rain, river crossings, clerical errors, and cavalry raids.

Casualty lists gives the number of men in a unit who were killed, wounded, or went missing in an engagement. However, combat threw armies into administrative chaos and the accounting done in the hours or days immediately following a battle often raises as many questions as it answers. For example: Who are the missing? Weren’t many of these soldiers killed and not found? What, exactly, qualifies a wound and did armies account for this the same way? What became of wounded soldiers? Did they rejoin their unit; did they return home; did they die?

A wholly accurate count will almost certainly never be made. The effects of this devastating conflict are still felt today.

“Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

–Abraham Lincoln, 2nd Inaugural Address