About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

At the end of what had been a long and difficult day, Sgt. Maj. Christian A. Fleetwood of the 4th United States Colored Infantry recorded in his diary that he “Charged with the 6th at daylight and got used up…saved colors.” Terse though it may be, Fleetwood’s entry opens a window onto a tale of heroism that is extraordinary, even by the standards of the American Civil War.

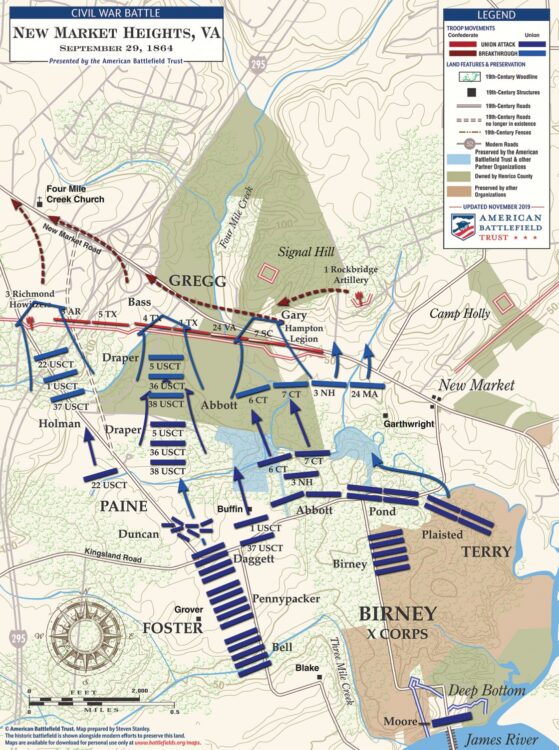

On Sept. 29, 1864, during the Battle of New Market Heights (part of the larger Battle of Chaffin’s Farm) near Richmond, several regiments of United States Colored Troops launched an assault on a well-fortified Southern position at the gates of the Confederate capital. Because of this action, 14 black soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor, the U.S. military’s highest decoration for acts of valor in combat. These men represent the largest group of African-Americans from a single battle to be so recognized.

They fought in hellish conditions. New Market Heights – a portion of which has been preserved by the Civil War Trust – was defended by one of the most storied units in Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, the Texas Brigade. Formerly commanded by John Bell Hood, the Texans were now led by John Gregg. Joining the Texans was a brigade of dismounted cavalry led by Martin W. Gary which included Hampton’s Legion, another legendary unit. Artillery batteries anchored each end of the Confederate line, exposing the Federal flanks to deadly enfilading fire. The defenders were protected by the trenches from which they fought, plus formidable natural and artificial obstacles, including two lines of abatis, and a swamp through which the Union attackers had to wade while under enemy fire.

The brave black soldiers in blue assigned the task of taking that position were undeterred, successfully carrying the rebel works and opening the way to the capital. Indeed, a Confederate soldier later admitted, “upon 29th September, Richmond came nearer to being captured, and that, too, by negro troops, than it ever did during the whole war.”

This victory came at tremendous cost. The attack on New Market Heights fell primarily on two African-American brigades with a combined strength of just over 2,000 men. When the smoke cleared, there were well over 800 casualties, including more than 130 dead.

The attackers at New Market Heights were remarkable individuals, none more so than the 14 men awarded the Medal of Honor: William H. Barnes, Powhatan Beaty, James H. Bronson, Christian A. Fleetwood, James Gardiner, James H. Harris, Thomas R. Hawkins, Alfred B. Hilton, Milton M. Holland, Miles James, Alexander Kelly, Robert A. Pinn, Edward Ratcliff, and Charles Veal.

The stories of Fleetwood, James, and Beaty illustrate just how impressive these men were.

A free African-American from Baltimore, Christian Fleetwood helped found one of the first black-owned newspapers in the South before enlisting in the 4th USCT in 1863. By the time of the New Market Heights assault, he had been promoted to sergeant major. During the combat, Fleetwood witnessed his regiment’s flag bearer go down. Rushing forward, he seized the national colors, carrying them throughout the rest of the fight and somehow surviving what he later described as “a deadly hailstorm of bullets, sweeping men down as hailstones sweep the leaves from the trees.” Several months later, the white officers of Fleetwood’s regiment organized a petition calling for him to receive an officer’s commission, stating “they would gladly welcome him as one of themselves.” The War Department denied the request. After the war, Fleetwood continued to serve the public, working in several government positions and commanding a battalion in the D.C. National Guard.

Born enslaved in Virginia, Miles James was a corporal in the 36th USCT when he fought at New Market Heights. His heroism in battle is described by his Medal of Honor citation: “Having had his arm mutilated, making immediate amputation necessary, loaded and discharged his piece with one hand and urged his men forward; this within 30 yards of the enemy’s works.” After the amputation, James requested permission to stay in the army. His commanding officer supported the request, writing, “He is one of the bravest men I ever saw. . .He is worth more with his single arm, than a half dozen ordinary men.”

Like Miles James, Powhatan Beaty was born into slavery in Virginia. A sergeant in the 5th USCT, Beaty played a critical role in the Union’s victory at the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm. When every officer in his company was killed or wounded, Beaty took command. Keeping his men organized in the face of heavy fire, Beaty led them forward in an attack that broke the Confederate line. After the war, he became a prominent Shakespearean actor, performing across the nation to rave reviews. A man of many talents, he also wrote a play that focused on the transition from slavery to freedom. In the early 21st century, a highway bridge near Richmond was named in Beaty’s honor.

The attackers at New Market Heights punched a hole in the Confederate defenses around Richmond. That the rest of the Union army was unable to exploit this opening takes nothing away from their achievement. Thomas Morris Chester, then the only black correspondent for a major daily newspaper, declared that the victorious division had “covered itself with glory” and predicted that it had “wiped out effectually the imputation against the fighting qualities of the colored troops.”