About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

This section examines the changes that took place in voting, nominating procedures, party organization, and campaign strategies between 1820 and 1840; and explains why new political parties emerged in the United States between the 1820s and the 1850s and how these parties differed in their principles and their bases of support.

You will learn about the religious, cultural, and social factors that gave rise to efforts to suppress the drinking of hard liquor; to rehabilitate criminals; establish public schools; care for the mentally ill, the deaf, and the blind; abolish slavery; and extend women’s rights, as well as about the efforts of authors and artists to create distinctly American forms of literature and art.

In addition, you will read about the Native Americans and Mexicans who lived in the trans-Mississippi West; about the exploration of the Far West and the forces that drove traders, missionaries, and pioneers westward; and the way that United States acquired Texas , the Great Southwest, and the Pacific Northwest by annexation, negotiation, and war.

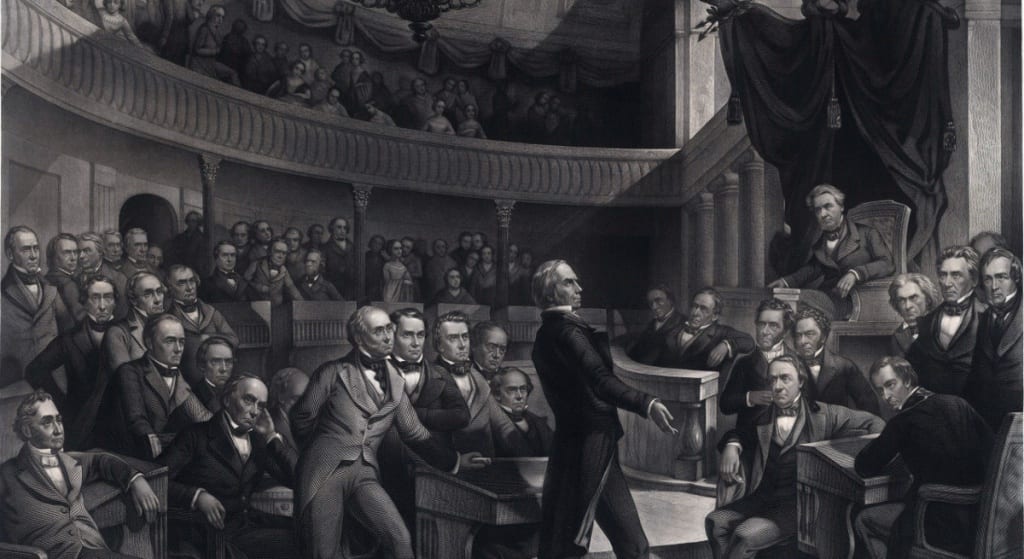

Finally, you will read about the diverging economic developments that contributed to growing sectional differences between the North and South, and about the Compromise of 1850, including the Fugitive Slave Law; the demise of the Whig Party and the emergence of the Republican Party; the Kansas-Nebraska Act; violence in Kansas; the controversial Supreme Court decision in the case of Dred Scott; and John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry.

Throughout the Western world, the end of the Napoleonic Wars brought an end to a period of global war and revolution and the start of a new era of rapid economic growth. For Americans, the end of the War of 1812 unleashed the rapid growth of cities and industry and a torrent of expansion westward. The years following the war also marked a notable advance of democracy in American politics. Property qualifications for voting and office holding were abolished; voters began to directly elect presidential electors, state judges, and governors; and voting participation skyrocketed. In addition, the antebellum era saw a great surge in collective efforts to improve society through reform. Unprecedented campaigns sought to outlaw alcohol, guarantee women’s rights, and abolish slavery.

Rapid territorial expansion also marked the antebellum period. Between 1845 and 1853, the nation expanded its boundaries to include Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. The United States annexed Texas in 1845; partitioned the Oregon country in 1846 following negotiations with Britain; wrested California and the great Southwest from Mexico in 1848 after the Mexican War; and acquired the Gadsden Purchase in southern Arizona from Mexico in 1853.

The period’s most fateful development was a deepening sectional conflict that brought the country to the brink of civil war. The addition of new land from Mexico raised the question that would dominate American politics during the 1850s: whether slavery would be permitted in the western territories. The Compromise of 1850 attempted to settle this issue by admitting California as a free state but allowing slavery in the rest of the Mexican cession. But enactment of the Fugitive Slave Law as part of the compromise exacerbated sectional tensions. The question of slavery in the territories was revived by the 1854 decision to open Kansas and Nebraska territories to white settlement and decide the status of slavery according to the principle of popular sovereignty. Sectional conflict was intensified by the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision, which declared that Congress could not exclude slavery from the western territories; by John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry; and by Abraham Lincoln’s election as president in 1860.

The period from 1820 to 1840 was a time of important political developments. Property qualifications for voting and officeholding were repealed; voting by voice was eliminated. Direct methods of selecting presidential electors, county officials, state judges, and governors replaced indirect methods. Voter participation increased. A new two-party system replaced the politics of deference to elites. The dominant political figure of this era was Andrew Jackson, who opened millions of acres of Indian lands to white settlement, destroyed the Second Bank of the United States, and denied the right of a state to nullify the federal tariff.

After the War of 1812, the American economy grew at an astounding rate. The development of the steamboat by Robert Fulton revolutionized water travel, as did the building of canals. The construction of the Erie Canal stimulated an economic revolution that bound the grain basket of the West to the eastern and southern markets. It also unleashed a spurt of canal building. Eastern cities experimented with railroads which quickly became the chief method of moving freight. The emerging transportation revolution greatly reduced the cost of bringing goods to market, stimulating both agriculture and industry. The telegraph also stimulated development by improving communication. Eli Whitney pioneered the method of production using interchangeable parts that became the foundation of the American System of manufacture. Transportation improvements combined with market demands stimulated cash crop cultivation. Agricultural production was also transformed by the iron plow and later the mechanical thresher. Economic development contributed to the rapid growth of cities. Between 1820 and 1840, the urban population of the nation increased by 60 percent each decade.

Two currents in religious thought–religious liberalism and evangelical revivalism–had enormous impact on the early republic. Religious liberalism was an emerging form of humanitarianism that rejected the harsh Calvinist doctrines of original sin and predestination. Its preachers stressed the basic goodness of human nature and each individual’s capacity to follow the example of Christ. At the same time, enthusiastic religious revivals swept the nation in the early 19th century. The revivals inspired a widespread sense that the nation was standing close to the millennium, a thousand years of peace and brotherhood when sin, war, and tyranny would vanish from the earth. In addition, the growth of other religions–African American Christianity, Catholicism, Judaism, the Mormon Church–reshaped America’s religious landscape.

During the first half of the 19th century, reformers launched unprecedented campaigns to reduce drinking, establish prisons, create public schools, educate the deaf and the blind, abolish slavery, and extend equal rights to women. Increasing poverty, lawlessness, violence, and vice encouraged efforts to reform American society. So, too, did the ideals enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, the philosophy of the Enlightenment, and liberal and evangelical religion. Reform evolved through three phases. The first phase sought to persuade Americans to lead more Godly daily lives. Moral reformers battled profanity and Sabbath breaking, attacked prostitution, distributed religious tracts, and attempted to curb the use of hard liquor. Social reformers sought to solve the problems of crime and illiteracy by creating prisons, public schools, and asylums for the deaf, the blind, and the mentally ill. Radical reformers sought to abolish slavery and eliminate racial and gender discrimination and create ideal communities as models for a better world.

At the end of the 18th century, the United States had few professional writers or artists and lacked a class of patrons to subsidize the arts. But during the decades before the Civil War, distinctively American art and literature emerged. In the 1850s, novels appeared by African-American and Native American writers. Mexican-Americans and Irish immigrants also contributed works on their experiences. Beginning with historical paintings of the American Revolution, artists attracted a large audience. Landscape painting also proved popular. An indigenous popular culture also emerged between 1800 and 1860, consisting of penny newspapers, dime novels, and minstrel shows.

Until 1821, Spain ruled the area that now includes Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah. The Mexican war for independence opened the region to American economic penetration. Government explorers, traders, and trappers helped to open the West to white settlement. In the 1820s, thousands of Americans moved into Texas, and during the 1840s, thousands of pioneers headed westward toward Oregon and California, seeking land and inspired by manifest destiny, the idea that America had a special destiny to stretch across the continent. Between 1844 and 1848 the United States expanded its boundaries into Texas, the Southwest, and the Pacific Northwest. It acquired Texas by annexation; Oregon and Washington by negotiation with Britain; and Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, and Wyoming as a result of war with Mexico.

In the decades before the Civil War, northern and southern development followed increasingly different paths. By 1860, the North contained 50 percent more people than the South. It was more urbanized and attracted many more European immigrants. The northern economy was more diversified into agricultural, commercial, manufacturing, financial, and transportation sectors. In contrast, the South had smaller and fewer cities and a third of its population lived in slavery. In the South, slavery impeded the development of industry and cities and discouraged technological innovation. Nevertheless, the South was wealthy and its economy was rapidly growing. The southern economy largely financed the Industrial Revolution in the United States, and stimulated the development of industries in the North to service southern agriculture.

For forty years, attempts were made to resolve conflicts between North and South. The Missouri Compromise prohibited slavery in the northern half of the Louisiana Purchase. The acquisition of vast new territories during the 1840s reignited the question of slavery in the western territories. The Compromise of 1850 was an attempt to solve this problem by admitting California as a free state but allowing slavery in the rest of the Southwest. But the compromise included a fugitive slave law opposed by many Northerners. The Kansas-Nebraska Act proposed to solve the problem of status there by popular sovereignty. But this led to violent conflict in Kansas and the rise of the Republican Party. The Dred Scott decision eliminated possible compromise solutions to the sectional conflict and John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry convinced many Southerners that a majority of Northerners wanted to free the slaves and incite race war.