About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

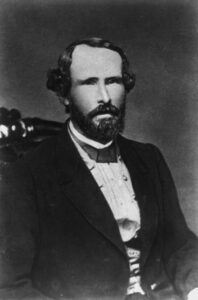

George Wythe Randolph was a lawyer, Confederate general, and, briefly, Confederate secretary of war during the American Civil War (1861–1865). The grandson of former U.S. president Thomas Jefferson, Randolph hailed from an elite Virginia family but largely shunned public life until John Brown‘s raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859. He supported secession, founded the Richmond Howitzers, joined the Confederate army, and fought at the Battle of Big Bethel (1861). Appointed the Confederacy’s third secretary of war in March 1862, he helped to reform the War Department at a time when the Confederate capital at Richmond was threatened by Union general George B. McClellan‘s Peninsula Campaign (1862). Randolph helped to improve procurement and authored the Confederacy’s first conscription law, having already done the same for Virginia. His independence and focus on the strategic importance of the West put him into conflict with Confederate president Jefferson Davis, and he resigned in November 1862, his health failing. He died of tuberculosis in 1867.

George Wythe Randolph was a lawyer, Confederate general, and, briefly, Confederate secretary of war during the American Civil War (1861–1865). The grandson of former U.S. president Thomas Jefferson, Randolph hailed from an elite Virginia family but largely shunned public life until John Brown‘s raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859. He supported secession, founded the Richmond Howitzers, joined the Confederate army, and fought at the Battle of Big Bethel (1861). Appointed the Confederacy’s third secretary of war in March 1862, he helped to reform the War Department at a time when the Confederate capital at Richmond was threatened by Union general George B. McClellan‘s Peninsula Campaign (1862). Randolph helped to improve procurement and authored the Confederacy’s first conscription law, having already done the same for Virginia. His independence and focus on the strategic importance of the West put him into conflict with Confederate president Jefferson Davis, and he resigned in November 1862, his health failing. He died of tuberculosis in 1867.

George Wythe Randolph was born at Monticello in Albemarle County on March 10, 1818, the son of the soon-to-be Virginia governor Thomas Mann Randolph Jr. and Martha Jefferson Randolph. Named for George Wythe, a Virginia delegate to the Second Continental Congress and a signer of the Declaration of Independence, Randolph was the youngest of twelve children. His father accrued large debts that ultimately wrecked the family’s financial and social standing. Wanting to shield her son from the family’s misfortunes, Martha Randolph sent her son to preparatory schools in Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Washington, D.C. At age thirteen, he enlisted as a midshipman in the United States Navy, sailing on the USS John Adams and USS Constitution to the Mediterranean Sea. (He contracted tuberculosis while at sea, but the disease went into a long remission.) Returning to the United States at the age of nineteen, Randolph trained at the Naval School in Norfolk, Virginia.

While still in the navy, he attended the school his grandfather founded, the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, at a time when the institution was dogged by student drunkenness and gambling. Finding a mentor in George Tucker—a former congressman, a novelist, and an essayist—Randolph studied economics, history, and political science. After two years, he resigned from the navy and read the law. On October 12, 1840, he was admitted to the Albemarle County bar, practicing in Charlottesville until just prior to 1850, when he grew tired of small-town life and moved to Richmond. There he became a civic leader, founding the Richmond Mechanics’ Institute and serving as an officer of the Virginia Historical Society. He also met the widow Mary Elizabeth Adams Pope, whom he married in New Orleans, Louisiana, on April 10, 1852.

Randolph had largely shunned politics, but John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in October 1859 inflamed sectional tensions and served to radicalize Randolph. He organized the Richmond Howitzers, a light-artillery unit armed with short-range howitzers converted from naval use, and marched it to Charles Town, Virginia (now West Virginia). There the unit contributed to prison security during Brown’s trial and, in December, his execution. Randolph was elected as a delegate to the Virginia Convention of 1861, which met in Richmond in February and for two and half months hotly debated the question of secession.

On April 12, Randolph and two other Virginia delegates—William B. Preston and Alexander H. H. Stuart—met in Washington, D.C., with the newly elected U.S. president, Abraham Lincoln, hoping to dissuade him from forcefully resupplying the federal garrison at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, and thereby provoking war. Lincoln vowed to meet force with force, however, and that night Confederates fired on Sumter. On April 17, after Lincoln responded with a call for 75,000 volunteers, the Virginia convention voted to secede. In the meantime, Randolph served on the convention’s military committee and helped to organize the state’s defenses and draft a conscription law based on European models.

Randolph was commissioned a major in the Virginia militia and his Richmond Howitzers were placed under the command of John Bankhead Magruder. Quickly promoted to colonel, Randolph was chief of artillery with Magruder’s Army of the Peninsula at the Battle of Big Bethel in York County and Hampton on June 10, 1861. Virginia’s first full-scale battle of the war resulted in a Confederate victory and praise for Randolph, who went on to design the fortifications at Yorktown, anticipating Union general George B. McClellan’s amphibious invasion of the peninsula the following spring. On February 12, 1862, Randolph was promoted to brigadier general and assigned to command the defenses at Suffolk.

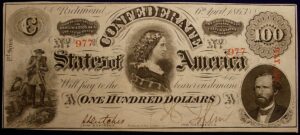

Randolph was not in Suffolk long. On March 18, 1862, Confederate president Jefferson Davis appointed him secretary of war to replace the outgoing Judah P. Benjamin, who had been censured by the Confederate Congress after the loss of Roanoke Island, North Carolina. Responsibilities at the War Department could be overwhelming. The Confederate army needed to be fed, equipped, and transported. Additional soldiers needed to be recruited. Issues of long-term strategy needed to be hashed out and coordinated between the Eastern and Western theaters. The egos and ambitions of generals, congressmen, and the president needed to be coddled.

His most immediate concern, perhaps, was McClellan’s march up the peninsula between the York and James rivers, a campaign that threatened Richmond. Working with Davis, his adviser Robert E. Lee, and the commander in the field, Joseph E. Johnston, Randolph helped to administrate the Confederate response. After Johnston’s wounding at the Battle of Seven Pines–Fair Oaks, Lee took over and defeated McClellan in the Seven Days’ Battles. McClellan’s immediate threat neutralized, the secretary of war began an unusual program of centralized economic planning, in which he proposed to feed and supply his troops by exchanging cotton with the North for food and other supplies. The plan failed, but in a successful effort to provide the Confederate armies with fresh recruits, he also helped to author a conscription law much like the one he had written for Virginia in 1861.

Randolph was known most for his insistence on strengthening the Confederacy’s military position in the southern and western parts of the country. Believing the Confederacy could not hold its territories if it left its chief ports in jeopardy, Randolph, in conjunction with Davis, drew up preliminary plans to retake New Orleans, which had fallen to the Union in April 1862. Plans remained just plans, however, and Randolph became increasingly frustrated with Davis’s Virginia-centric approach to the war. He also chafed at the president’s well-known habit of micromanaging his subordinates. (Before the war, when Davis was U.S. secretary of war, he had fought titanic battles with the army’s commanding general, Winfield Scott, over the minuscule details of expense reports.) His tuberculosis back and his health growing more fragile, Randolph resigned on November 15, 1862.

After briefly considering a return to field command, Randolph instead resigned from the army. He lived in Richmond during the bread riot on April 1, 1863, and advocated for the plight of workers. Randolph’s wife, Mary Randolph, meanwhile, was president of the Richmond Ladies’ Association. One of Richmond’s most prestigious organizations, it included as members the wives of various government officials, including the famous diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut. As noted by the historian Caroline E. Janney, Mary Randolph—perhaps echoing her husband’s quasi-socialist inclinations—suggested to the group that it divides its donated goods equally among both Union and Confederate wounded and prisoners, an idea not met with universal approval among the women. “Some shrieked in wrath at the bare idea of putting our noble soldiers on par with Yankees—living, dying, or dead,” Chesnut wrote. In the end, the association stuck to serving the needs of Confederate soldiers only.

In November 1864, Randolph and his wife evaded the Union blockade and spent the rest of the war in England and France, returning to the United States in September 1866. He died on April 3, 1867, at Edgehill, a family estate in Albemarle County. He is buried at Monticello.

Goldberg, D. E. (n.d.). Randolph, George Wythe (1818–1867). Retrieved March 29, 2021, from https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/randolph-george-wythe-1818-1867/