About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

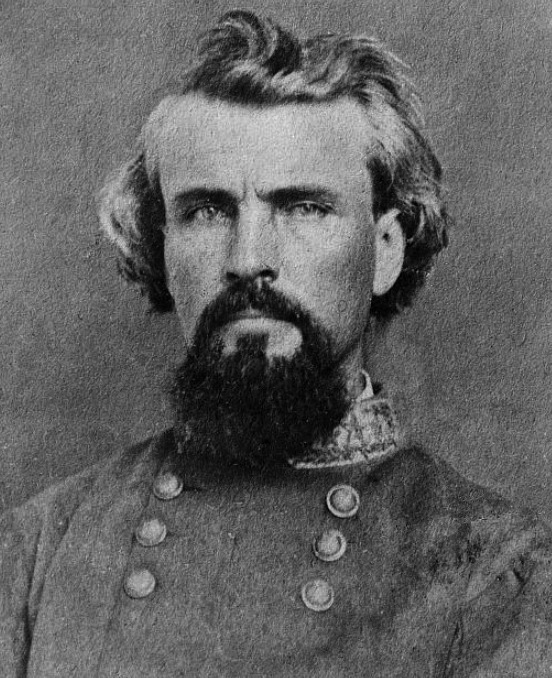

In 1871, Gen. Forrest was called before a Congressional Committee. Forrest testified before Congress personally for over four hours.

Here’s part of the transcript of Forrest’s testimony to that 1871 hearing:

“The reports of Committees, House of Representatives, second session, forty-second congress,” P. 7-449. (see link here )

“The primary accusation before this board is that Gen. Forrest was a founder of The Klan, and its first Grand Wizard, So it shall address those accusations first.”

Forrest took the witness stand on June 27th,1871. Building a railroad in Tennessee at the time, Gen Forrest stated he ‘had done more, probably than any other man, to suppress this violence and difficulties and keep them down, had been vilified and abused in the (news) papers, and accused of things I never did while in the army and since. He had nothing to hide, wanted to see this matter settled, our country quiet once more, and our people united and working together harmoniously.’

Asked if he knew of any men or combination of men violating the law or preventing the execution of the law: Gen Forest answered emphatically, ‘No.’ (A Committee member brought up a ‘document’ suggesting otherwise, the 1868 newspaper article from the “Cincinnati Commercial”. That was their “evidence”, a news article.)

Forrest stated …any information he had on the Klan was information given to him by others.

Sen. Scott asked, ‘Did you take any steps in organizing an association or society under that prescript (Klan constitution)?’

Forrest: ‘I DID NOT’ Forrest further stated that ‘..he thought the Organization (Klan) started in middle Tennessee, although he did not know where. It is said I started it.’

Asked by Sen. Scott, ‘Did you start it, Is that true?’

Forrest: ‘No Sir, it is not.’

Asked if he had heard of the Knights of the White Camellia, a Klan-like organization in Louisiana,

Forrest: ‘Yes, they were reported to be there.’

Senator: ‘Were you a member of the order of the white Camellia?’

Forrest: ‘No Sir, I never was a member of the Knights of the White Camellia.’

Asked about the Klan :

Forrest: ‘It was a matter I knew very little about. All my efforts were addressed to stop it, disband it, and prevent it….I was trying to keep it down as much as possible.’

Forrest: ‘I talked with different people that I believed were connected to it, and urged the disbandment of it, that it should be broken up.'”

The following article appeared in the New York Times on June 27th, “Washington, 1871. Gen Forrest was before the Klu Klux Committee today, and his examination lasted four hours. After the examination, he remarked that the committee treated him with much courtesy and respect.”

Gen. Forrest was NOT the ‘first Grand Wizard of the KKK’. For the correct information on that, here are the actual documented facts :

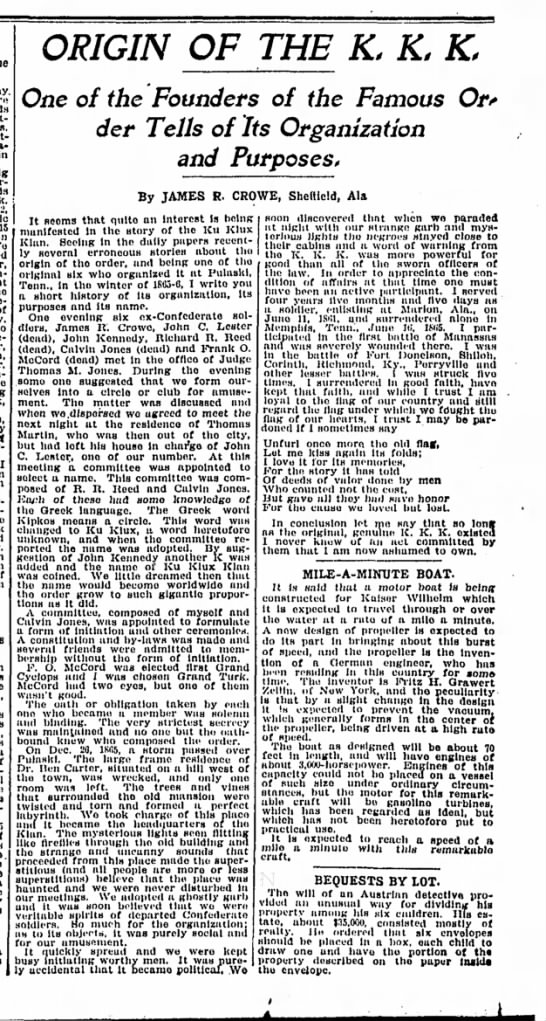

Actually, the “kuklos” was started in Pulaski, Tennessee, just before Christmas 1865, by six ex-Confederate officers, and was a sort of social club for Confederate officers.

Nathan Bedford Forrest had absolutely nothing to do with the founding of the Ku Klux Klan.

And even within the history of the Klan, differences must be noted between the Klan of the 1860s and the Klan of today.

The KKK that was reorganized in 1915 had a reputation as a bigoted and sometimes violent organization, fueled by hate and ignorance and thriving on fear and intimidation. But that wasn’t always the case. The original KKK of the 1860s was organized as a fun club, or social club, for Confederate veterans. Many historians agree that if a YMCA had been available in the town of Pulaski, Tenn., the KKK might never have existed. It was also a social aid and welfare society whose main purpose was to protect those who had been dispossessed by the War while helping maintain law and order during the so-called “Reconstruction”. Not only did this early kkk have thousands of Black members, but there was also an all-black kkk chapter in Nashville at one time. (credit goes to Lochlainn Seabrook for that documented info).

On Dec. 24, 1865, six young Confederate veterans met in the law office of Judge Thomas M. Jones, near the courthouse square in Pulaski. Their names were James R. Crowe, Calvin E. Jones, John B. Kennedy, John C. Lester, Frank O. McCord, and Richard B. Reed. All had been CSA officers and were lawyers, except Kennedy and McCord, who had each served as a private in the Confederate army. The meeting resulted in the idea of forming a social club, an 1860s version of the VFW or American Legion.

Notice, Gen. Forrest was not present at the founding meeting.

Their number quickly grew, and in meetings that followed, the men selected a name based on the Greek word “kuklos” meaning circle, from which they derived the name Ku Klux. Perhaps bowing to their Scotch-Irish ancestry, and to add alliteration to the name, they included “clan,” spelled with a K. And so, quite innocently, a new social club called the Ku Klux Klan was created to provide recreation for Confederate veterans.

McCord, whose family owned the town’s weekly newspaper, the Pulaski Citizen, printed mysterious-sounding notices of meetings and club activities. As other newspapers picked up his stories about the Klan, word spread and the organization grew.

The actual Grand Wizard of the KKK at that time was former CSA General, George W. Gordon, a resident of Pulaski, Tennessee, where the club was formed. He was often identified with the Klan and personally claimed to have been involved with the group. His robes and Klan regalia are in the Tennessee State Museum.

When the war ended, Forrest was virtually broke, having spent most of his estimated pre-war fortune of $1.5 million outfitting his troops. He was spending his time between business ventures in Memphis and his farm in Mississippi. Organizations such as the Klan were farthest from his mind.

After the War, General Forrest made a speech to the Memphis City Council (then called the Board of Aldermen). In this speech, he said that there was no reason that the black man could not be doctors, store clerks, bankers, or any other job equal to whites. They were part of our community and should be involved and employed as such just like anyone else. In another speech to Federal authorities, Forrest said that many of the ex-slaves were skilled artisans and needed to be employed and that those skills needed to be taught to the younger workers. If not, then the next generation of blacks would have no skills and could not succeed, and would become dependent on the welfare of society. Forrest’s words went unheeded. The Memphis & Selma Railroad was organized by Forrest after the war to help rebuild the South’s transportation and to build the ‘new South’. Forrest took it upon himself to hire blacks as architects, construction engineers and foremen, train engineers and conductors, and other high-level jobs. In the North, blacks were prohibited from holding such jobs.

When Forrest was ‘elected’ Grand Wizard of the Klan in mid-1867 at the Maxwell House Hotel in Nashville, he wasn’t even in town. He was ‘elected’ in absentia. That doesn’t count as ‘being elected’. The best scholarly research shows that Forrest never “led the Klan,” he never “rode with” the Klan, nor did he ever own any Klan paraphernalia. It has been speculated by many that the reason for his name being submitted for the election was partly a prank, and mostly to discredit him for his work toward black equality such as his hiring practices for his railroad company. Forrest was a civil rights pioneer.

So there you have it. There is no reason to think of Gen. Forrest with anything but admiration and respect. If anyone still thinks badly of Gen. Forrest, that is a reflection of their own bad character and does not take away from Gen. Forrest’s outstanding contributions to humanity.

Always remember, the “kuklos” of the late 1860s wasn’t even remotely like the US-flag-waving racist mob of the early 20th century.

I am, general, yours, very respectfully,

N. B. FORREST,

Major-General.

(From the OFFICIAL RECORDS

WAR OF THE “REBELLION”)

Forrest’s Speech to the Pole Bearers

Forrest (1821-1877) was a famous Southern military leader, a brilliant strategist, and a gentleman who made his mark in what Southerners call the War of Northern Aggression or War Between The States.

To paint every general on the losing side as a racist simply because you don’t like the South is a travesty that the facts of history will knock downtime and time again.

Yes, Forrest was a great general in an unpopular war, but when the war ended, Forrest accepted the outcome and then sought reconciliation with those around him.

He worked diligently to rebuild the New South and earnestly to generate employment for black Southerners.

His leadership and character did not fade because the South had been defeated. Instead, he used who he was, accepted the outcome, and used his fame and talents for others’ good.

At an early convention of the Pole-Bearers, whose beginnings prefaced the NAACP, it was Forrest who was invited to speak. History records no disrespect at the meeting; instead, both the Pole-Bearers and Forrest behaved with mutual respect and decorum. He was the guest speaker, and historically the first white invited to be the keynote speaker.

Forrest was asked because the group was said to have wanted to extend union and peace to others, but what happened in further actions was even more important.

On July 4, 1875, the event began with a young black woman, the daughter of a leader of the Pole-Bearers, offering him a small bouquet of flowers signifying the peace intended.

Forrest received the flowers and then spoke from his heart to the gathering. His actions and recorded words testify that this gentleman was in truth a civil rights advocate, a believer in the rights of all people.

Among the statements he made that day: “I came here with jeers of some white people who think what I am doing is wrong. We were born on the same soil, breathe the same air, live in the same land, and why should we not be brothers and sisters. I believe I can exert some influence … and shall do all in my power to elevate every man and to depress none. I want to elevate you to take positions in law offices, in stores, on farms, and wherever you are capable of going.”

He apologized for having no formal speech, but continued, ” Many things have been said about me that are wrong, and which black and white persons here who stood by me through the war can contradict.”

“I feel that you are free men, I am a free man, and we can do as we please. I came here as a friend and whenever I can serve any of you I will do so. We have one union, one flag, one country; therefore, let us stand together. Although we differ in color, we should not differ in sentiment.”

“Do your duty as citizens, and if any are oppressed, I will be your friend. I thank you for the flowers, and assure you that I am with you in heart and hand.”

It should be noted that both black and white soldiers fought under Forrest against the North. Many were in attendance at this Memphis address. When Forrest’s cavalry abdicated in May of 1865, the muster included 65 black soldiers. Forrest described those gentlemen as soldiers amid his finest.

Yes, Forrest was a Southern general whose war strategies were unmatched. Yes, the war that began over states’ rights brought forth a welcome transition to the civil rights we are so thankful for today.

The transcript of the 1871 Congressional Committee can be found here.

Pages 3 to 41 contain Gen. Forrest’s testimony.

This link connects to the record of Gen. Forrest’s testimony concerning the ‘ku klux’ and the state of affairs in portions of Georgia and Tennessee in which Gen. Forrest had traveled. There are only two mentions of Fort Pillow in this link, each time it is mentioned only in passing, not in depth.

We are still looking for the rumored transcript of the committee in which Gen. Sherman supposedly questions Gen. Forrest; it is probably an urban legend. Sherman was not a member of Congress in 1871.

Many thanks to the Library of Congress for providing this link.

As for Fort Pillow, Gen. Forrest received many requests from residents around the fort asking him to come stop the Union soldiers from looting and pillaging the area and from committing atrocities (murders, rapes, random shootings, etc.) upon the people. When the battle started, many of the Union troops were drunk and refused to surrender when the battle was clearly lost. Afterward, Gen. Forrest had the most severely wounded Union soldiers transferred to a Union gunboat.

The Yankee newspapers created all sorts of lies to cover up the atrocities committed by the Union troops and their refusal to abide by the terms of surrender, so they invented tales of butchery by Forrest’s troops. After learning all the facts of the battle and the Union atrocities committed in the weeks before the battle, one has to admire the restraint of the Confederates. The Union Congressional “investigation” of 1864 was a smear job, with “witnesses” who were later proven to have been over a hundred miles away at the time of the battle. Here is one account from a Union Soldier present at the battle:

Report of Lieut. Daniel Van Horn, Sixth U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery, of the capture of Fort Pillow.

MARCH 16-APRIL 14, 1864.–Forrest’s Expedition into West Tennessee and Kentucky.

O.R.– SERIES I–VOLUME XXXII/1 [S# 57]

HDQRS. SIXTH U.S. HEAVY ARTILLERY (COLORED),

Fort Pickering, Memphis, Tenn., April 14, 1864.

Lieut. Col. T. H. HARRIS,

Assistant Adjutant-General.

COLONEL: I have the honor to submit the following report of the battle and capture of Fort Pillow, Tenn.:

At sunrise on the morning of the 12th of April, 1864, our pickets were attacked and driven in, they making very slight resistance. They were from the Thirteenth Tennessee Cavalry.

Major Booth, commanding the post, had made all his arrangements for battle that the limited force under his command would allow, and which was only 450 effective men, consisting of the First Battalion of the Sixth U.S. Heavy Artillery, five companies of the Thirteenth Tennessee Cavalry, and one section of the Second U.S. Light Artillery (colored), Lieutenant Hunter.

Arrangements were scarcely completed and the men placed in the rifle-pits before the enemy came upon us and in ten times our number, as acknowledged by General Chalmers. They were repulsed with heavy loss; charged again and were again repulsed. At the third charge Major Booth was killed, while passing among his men and cheering them to fight.

The order was then given to retire inside the fort, and General Forrest sent in a flag of truce demanding an unconditional surrender of the fort, which was returned with a decided refusal.

During the time consumed by this consultation advantage was taken by the enemy to place in position his force, they crawling up to the fort.

After the flag had retired, the fight was renewed and raged with fury for some time, when another flag of truce was sent in and another demand for surrender made, they assuring us at the same time that they would treat us as “prisoners of war.”

Another refusal was returned, when they again charged the works and succeeded in carrying them. Shortly before this, however, Lieut. John D. Hill, Sixth U. S. Heavy Artillery, was ordered outside the fort to burn some barracks, which he, with the assistance of a citizen who accompanied him, succeeded in effecting, and in returning was killed.

Major Bradford, of the Thirteenth Tennessee Cavalry, was now in command. At 4 o’clock the fort was in possession of the enemy, every man having been either killed, wounded, or captured.

There never was a surrender of the fort, both officers and men declaring they never would surrender or ask for quarter.

As for myself, I escaped by putting on citizens clothes, after I had been some time their prisoner. I received a slight wound of the left ear.

I cannot close this report without adding my testimony to that accorded by others wherever the black man has been brought into battle. Never did men fight better, and when the odds against us are considered it is truly miraculous that we should have held the fort an hour. To the colored troops is due the successful holding out until 4 p.m. The men were constantly at their posts, and in fact through the whole engagement showed a valor not, under the circumstances, to have been expected from troops less than veterans, either white or black.

The following is a list of the casualties among the officers as far as known: Killed, Maj. Lionel F. Booth, Sixth U.S. Heavy Artillery (colored); Maj. William F. Bradford, Thirteenth Tennessee Cavalry; Capt. Theodore F. Bradford, Thirteenth Tennessee Cavalry; Capt. Delos Carson, Company D, Sixth U.S. Heavy Artillery (colored); Lieut. John D. Hill, Company C, Sixth U.S. Heavy Artillery (colored); Lieut. Peter Bischoff, Company A, Sixth U.S. Heavy Artillery (colored). Wounded, Capt. Charles J. Epeneter, Company A, prisoner; Lieut. Thomas W. McClure, Company C, prisoner; Lieut. Henry Lippett, Company B, escaped, badly wounded; Lieutenant Van Horn, Company D, escaped, slightly wounded.

I know of about 15 men of the Sixth U.S. Heavy Artillery (colored) having escaped, and all but 2 of them are wounded.

I have the honor to be, very respectfully, &c.,

DANIEL VAN HORN,

2d Lieut. Company D, Sixth U.S. Heavy Artillery (colored).

For a full accounting of the Fort Pillow battle, read “Confederate Victories At Fort Pillow” by Edward F. Williams III, published 1973 by Historic Trails, Inc., Memphis, TN and “The Campaigns of General Nathan Bedford Forrest and of Forrest’s Cavalry”, originally published in 1868 and reprinted in 1996. Both books can probably be found at Abes Books.

Here is a pretty good analysis of the Fort Pillow battle.

Another good article from the Armchair General

Good reference books:

“Nathan Bedford Forrest and the Battle Of Fort Pillow: The True Story” by Lochlainn Seabrook

“Forrest! 99 Reason To Love Nathan Bedford Forrest” by Lochlainn Seabrook

… and there are several other good books about Forrest by Lochlainn Seabrook at Sea Raven Press

Another interesting read: “Truth Of The War Conspiracy”