About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Legendary Rebel Lies In Remote Grave

Legendary Rebel Lies In Remote GraveBy Thomas E. Turner, Central Texas Bureau Of The News

Maysfield, Milam County — The ancient but neat Little River Cemetery is tucked away in a remote section of the eastern Milam County.

Nestled between the Brazos River and the misnamed Little River, the cemetery contains many graves of some of Texas’ first permanent settlers. The crumbling headstones list the names of Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, the Carolinas.

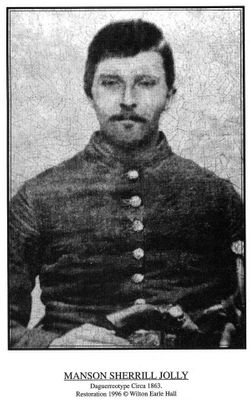

In the center of the cemetery, underneath a gaunt tree, is a simple stone slab marked “Sacred to the Memory of Manson S. Jolly, age 29 years.” A Masonic symbol is the only other marking on the headstone. A smaller slab, inscribed M.S.J., and a small bush mark the grave’s foot.

For decades even the natives of this Old-South region between Cameron and Hearne pondered the significance of that grave and its sparse markings. A few of the old-timers vaguely recalled that it was the end of the trail “for a Confederate soldier”, but that was about all.

Other Confederate graves nearby are marked much better —William D. Lindsey, Co. D, 17th. Alabama Inf, and the like.

And yet, the uncommunicative slab for Manson S. Jolly marks the grave of one of the Civil Wars’ most legendary figures.

In the cradle of the Confederacy, South Carolina they still talk and write of the exploits of a young rebel whose career outdoes fiction. He was — according to the sectional viewpoint — a brave, avenging Robin Hood, or a beastly bushwhacker.

In South Carolina, he will always be a classic symbol of the Unreconstructed Rebel who never surrendered. The career of Manse Jolly provides an insight into the depth and bitterness of the anti-Yankee sentiment that complicates the modem world of Selma, Alabama and some other festering social wounds.

Justified or not, the Civil War left Manse Jolly with a burning heritage of hate. The flames of bitterness were fed by the chaotic Reconstruction era he came home to, a time which even the most objective of historians generally concede is as dark a blot on American history as was the tragic fratricidal orgy itself.

Manse Jolly was, in real life, something right out of a John Wayne movie. In appearance, he resembled more a Henry Fonda in Civil War makeup. He was a backwoods farm boy with a strong Scottish strain and a sharpshooter’s eye that could put a bullet exactly where he wanted it. He could ride like a Comanche, an art which molded him into a Cavalry Sergeant as reckless and dangerous as any in fiction.

He stood 6 feet, 4 inches high, had red hair and the traditional temperament to match it, and blue eyes. He couldn’t have had much schooling, yet he wrote a beautiful script, highly literate for its time. Deadly serious in battle, with knife, pistol or rifle, his letters nevertheless reveal a wry sense of humor.

He was quite likely the champion Yankee killer of South Carolina, where the Civil War started and which suffered some of its most grievous effects.

From the accounts of Confederates who saw him do it, Manse Jolly fought through the entire war with a charmed-life zeal. It never really ended for him, until his ironic death in Texas.

The thing that Carolinians remember most vividly about Manse Jolly is the vow he swore to kill a quota of Yankees for each of the five brothers who died for the Confederacy. Four were killed in battles, the fifth died in an army hospital, a place not much safer than a battlefield in that war.

As usual in Civil War lore, undisputed facts are hard to come by in the Manse Jolly story — dates, spellings, and incidents are clouded in confusion or colored by sectional prejudice. Still, the part of the story fairly well documented is colorful enough.

Accounts vary as to whether Manse swore to kill five, or more, Yankees for each of his dead brothers. There is no agreement, either, on exactly how many he killed — estimates vary from about 15 on up to 100. It seems fairly certain Sgt. Jolly made his quota of Yankees — not counting a sizable number of “freeman.”

Like most bitter “Southerners of the Reconstruction” Jolly had a particular dislike for the freed slaves who guided Union troops or officials to the silver, gold, or horses that had been hidden by the destitute, defeated Rebels.

Most accounts make it plain that Jolly had no mercy for such persons, and he probably didn’t even include the many he dispatched in his grisly box score.

Some time ago a South Carolina man, David J. Watson, a retired engineer, bought the run-down little Jolly log home near Anderson, S.C., and remodeled it with great skill. Watson was, for 31 years, in charge of the physical plant at Clemson University — and is a leader in the area’s historical societies.

Watson says that some 75 or 60 years after the war an old well on the Jolly farm was cleaned out. It contained numerous skeletons and about a peck of corroded military uniform buttons — all marked ” U.S.” The well apparently was one of Manse Jolly’s disposal spots for Yankee soldiers.

Jolly enlisted in the Confederate forces in February 1861 barely two months after South Carolina led the secession parade of Southern States, and two months before the Civil War’s “cold war” phase burst into hot war at Fort Sumter.

An August, 1861 Furlough (containing his physical description) says he joined Co. H. of the 1st S. C. Infantry Regiment. Yet, newspaper accounts and statements of former comrades-in-arms list him as a member of Co. F., 1st C.C. Cavalry. He apparently went through most of the war from Manassas to Appomattox, as a cavalry scout.

One man who served with him recalled one night foray in which they crept up to a Yankee outpost of three Union soldiers, all of whom were quietly dispatched by Jolly’s knife. Another companion recalled Jolly leaving camp one night, and returning with the horse and saddle of a Union officer, which he politely presented to his captain.

He was apparently in Wade Hampton’s cavalry forces when Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox and headed homeward vowing never to surrender.

He came home to a miserable Anderson County occupied by Massachusetts troops, including Negroes, and later a Main regiment. Carpetbaggers, freed-men, and Union troops considered South Carolina the “soul of the session.” It was a time that explains, if not justifies, the deeply engrained resentment underlying today’s upheavals.

Whether by choice or by circumstance, the embittered “unsurrendered” Sgt. Jolly became a scourge of the occupiers. Some sympathetic accounts say Jolly was enraged by the mistreatment of a younger brother, and his mother, by Union soldiers. Since some of the explanations for his vendetta are obviously exaggerated (such as a version that his mother collapsed and died when his younger brother’s body was brought home) there is no clear-cut answer.

But rampage he did. No Union soldier or “freeman” collaborator was safe outside the occupation camp in Anderson. One at a time, and sometimes in batches, the thick woods that Manse Jolly knew like a squirrel swallowed them up. Many died from a sudden bullet. Others died with slashed throats.

Several contemporary accounts mention that Manse Jolly donned Yankee soldier uniforms often, a dangerous disguise which allowed him to capture other unsuspecting blue-clad soldiers. One time Manse wryly observed he was turning enemy soldiers over to “General Green”- meaning the green forest.

He obviously considered himself a guerrilla, carrying on the was against an occupation enemy. He circulated freely in his old haunts, even in Anderson. The Union didn’t know him by sight, and when the price on his head rose even as high a $10,000 there were no takers. Obviously, anyone attempting to collect it, in person or by proxy, would not have lived long enough to spend it. Some of the people of the area were nervous because of his activities, and the Yankee heat it focused, but to most of the people, he was a Robin Hood netting out justified justice.

Finally, though, Manse decided to leave. The most accepted explanation is that while he wasn’t worried about his own safety, his angry hunters were harassing his mother and sisters. His father apparently had died before the war began.

Manse Jolly’s departure for Texas is another colorful phase of his legend — he literally left in a blaze of glory according to Anderson County lore, based largely on old newspaper accounts.

On a Sunday, January 29, 1866 (the story goes), Jolly rode quietly into Anderson on his favorite horse, Dixie. A few blocks down the street from the camp of the Union troops, he reined up. Taking a deep breath, he pulled his hat down over his red hair, and put a pistol in each hand.

With the traditional rebel-yen piercing the calm day, he galloped pell-mell through the camp with both pistols blazing at anything that moved. The troops, understandably, were stunned into virtual statues until the yelling apparition had disappeared into protecting woods, leaving shocked and wounded soldiers in his wake.

Unless the date of the wild incident is wrong, it was still not until September 1866, that he finally left Anderson for Texas. Watson has copies of letters Jolly cautiously mailed his sister and mother en route to Texas. He traveled by way of Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana.

His letters are chatty, nostalgic, providing a good insight into the turbulent times. His traveling companions were Walter Largent, who had helped him harass the Yankees; F.D. Townsend, Thomas Herbert Williams, and a cousin, John M. Jolty.

They settled in Milam County, populated by many Southerners, including some relatives of Manse Jolly.

Manse had arrived on Dixie, and with some money, he had made trading horses en route. Some of the horses probably had belonged to “missing” Union men.

Jolly and his three companions — who were to become well-known families in the region with lots of present-day descendants — lived in a small farm building Manse labeled “Bachelor’s Hall” in his letters home. In one letter he calls it “Delectable Hall.” They worked long hours at raising cotton and wheat, and Manse worked at a gin.

On April 16, 1867, he wrote his sister: “I am more than pleased with Texas, but damn the people that live in it. Society is bad, no use for preachers out here…”

On June 29 he had another appraisal of frontier Texas: “The longer I stay the better satisfied I am but I say darn the most of the people. It has become a general custom amongst the lower class to use snuff. How distasteful it is in my sight to see them push forward a box of snuff and ask all around to dip with them corn is selling for 50 cts per bushel, flour 10 dollars per barrel, bacon 12 ½ cts per pound, beef from one to three cents …”

In that letter he noted, “I am strongly in the notion of getting married as a bachelor’s life is most miserable of all living creatures.”

He carrie d out his “strong notion” the following year, 1868. He married 19-year-old Elizabeth Mildred Smith, a daughter of Capt. John Grey (Jack) Smith, another South Carolinian. Walter Largent married Smith’s other daughter.

d out his “strong notion” the following year, 1868. He married 19-year-old Elizabeth Mildred Smith, a daughter of Capt. John Grey (Jack) Smith, another South Carolinian. Walter Largent married Smith’s other daughter.

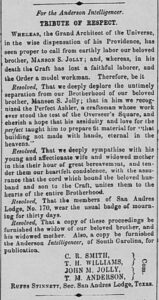

On July 12, 1869, John M. Jolly, the cousin who had come to Texas with Manse, wrote Manse’s Mother:

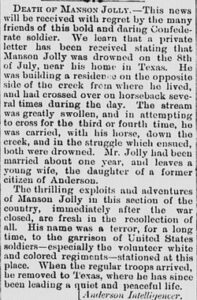

“Dear Aunt: It is under very sad circumstances that I write to you. It becomes my sad duty to inform you that Manson is dead. He was drowned on last Thursday evening 8th inst. The circumstances were these: We have had the highest rise of Little River that has been known for years. Manson was working on a house for himself which was on the opposite side of a small creek from where he was living. In returning from his work in the evening he attempted to swim the creek on his horse and he and the horse both drowned.”

“He had swam the creek (the letter continues) three times that day on the same horse. There were three men and a boy with him but they could render him no assistance. The water was 12 or 15 feet deep where he drowned in consequence of which his body could not be gotten immediately. It was about 18 hours before the body was found. In consequence of the high water, I could not be notified until the next day, and then I had to ride 30 miles to get him though I was in six miles when I started. He was buried on last Saturday 10th inst”

John Jolly concluded his doleful message: “Manson had made friends since we have been here and could he have lived, his future so far as human knowledge extends would have been bright. I feel as if I have lost a brother. Dear Aunt I hope that you will beable to bear up under this trouble. I shall be glad to hear from you and will take a pleasure in writing to you at any time. I am as ever, your nephew.”

Three weeks later Cousin John sent his aunt a lock of Manse’s hair.

According to Milam County’s District Clerk, Grady Allen, a Masonic historian, Manse was a Mason and was in the process of transferring his membership to Cameron’s lodge.

He was to have been accepted in it the night of the day he drowned perhaps one reason he was anxious to return home despite the floodwaters.

The main reason was that his young wife was about five months pregnant. In November 1869, she gave birth to a daughter, Ella Manson Jolly. She lived to be 61, mostly in Fort Worth, where she is buried. She married, at 22, a New Yorker, Thomas Beekman Van Tuyl — a circumstance which must have disturbed her Yankee-hating father even in death, Van Tuyl was a Colorado City and Fort Worth banker.

Manse’s two granddaughters are both living in Los Angeles; one is the wife of a salesman, the other is a Red Cross official.

Manse’s widow later wed a Colorado City man, apparently in her middle age. She died sometime after 1925, age 76, in Fort Worth.

The Clay County village of Jolly, near Wichita Falls, apparently is named after one of Manse’s relatives.

Sgt. Manson Jolly, who never surrendered, lies in his obscure grave near his friend and brother-in-law, Walter Largent, also dead at 29, and their father-in-law, Capt. Jack Smith. The spirit of many a Yankee soldier probably would have been pleased to know that a flooded Texas creek had accomplished what the Civil War and its aftermath couldn’t.