About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

In accordance with the authority conferred by this Congress, the Confederate President appointed John Slidell and James M. Mason diplomatic agents in October 1861, with the power to enter into conventions for treaties with England and France. They were commissioned to secure from these European powers recognition of the Confederate government as a nation, based upon the vast extent of territory, its large and intelligent population, its ample resources, its importance as a commercial nation, and withal the justice of its separation from the United States. It was expected that these statesmen would be able to convince Europe of the ability of the Confederate States to maintain a national existence, as belligerent rights had already been accorded. With all the usual credentials and necessary powers, the commissioners departed for Havana, Cuba, on the blockade-runner “Theodora,” where they arrived in safety and were presented to the captain-general of the island by the British consul, not in an official capacity but as gentlemen of distinction. Afterward, they went as passengers aboard a British merchant vessel, “The Trent,” carrying English mails and sailed for England.

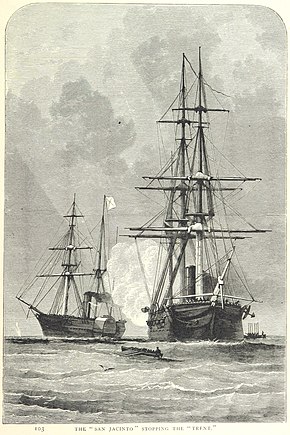

In the meantime Captain Charles Wilkes, U.S. N., commanding the United States sloop-of-war, “San Jacinto,” carrying thirteen guns, who appears to have had a zeal not according to knowledge, was busy in carrying out a purpose to capture the Confederate commissioners and executed his designs with success enough to produce a sensation which involved his government in a serious difficulty with England, from which extrication was gained only by very mortifying explanations. Cruising near the island on the alert for the “Trent,” Captain Wilkes sighted the approaching vessel on the high seas, and gave the command to “beat to quarters, hoist the colors and load the guns.” The next proceeding was to fire a shot across the bow of the “Trent,” which caused that vessel to display the British colors without arresting its onward speed. A shell from the “San Jacinto” across her course brought the “Trent” to without delay and Captain Wilkes then sent his executive officer with a guard of marines and a full-armed boat crew to board the British ship. Lieutenant Fairfax, the executive officer, went aboard, and informing Captain Moir of the “Trent” as to the object of his visit, asked for the passenger list, saying that he would search the vessel to find Mason and Slidell. But while the English captain was protesting against this breach of international law and refusing to show any papers, the two Confederate commissioners with their associates, Eustis and McFarland, appeared and united with the British officer in his protest.

At this juncture the other Federal officers in the armed. cutter came aboard with a number of marines and other armed men of the boat’s crew and the second cutter also appearing alongside Captain Wilkes formed a line outside the main deck cabin into which the Southern passengers had retired to pack their baggage. This show of force was followed by the actual compulsion which it was demanded should be used and by which the commissioners were forcibly transferred from under the English flag to the boat for confinement aboard the “San Jacinto.” The “Trent” was then permitted to pursue her voyage, while the “San Jacinto” steamed away with her prisoners to Fortress Monroe, and on arrival was hailed with the hearty laudations of Congress and the compliments of some portions of the press. Captain Wilkes for a brief moment was the pride of the nation. But in a few days, he heard himself condemned for his officiousness in terms that showed very clearly that he had involved his government in a very disagreeable and dangerous controversy with Great Britain.

The boarding of the “Trent” was an outrage of national amity which could not escape the indignation of all maritime nations. It was perpetrated by a zealot who was too stupid to foresee its ill effect on the relations which his own country was endeavoring to maintain with Europe, and it produced a sensation which for a while seemed to threaten the total failure of coercion. It is not surprising that on getting the full news of the event President Lincoln said to the attorney general: “I am not getting much sleep out of that exploit of Wilkes, and I suppose we must look up the law of the case. I am not much of a prize lawyer, but it seems to me pretty clear that if Wilkes saw fit to make that capture on the high seas, he had no right to turn his quarterdeck into a prize court.” The shrewd President saw that Wilkes could not let the “Trent” go free, while he bore away from her the American passengers as “contraband, “or as” conspirators,” thus choosing to determine himself a question which only an admiralty court duly constituted could adjudicate.

The President also soon realized that the rash act was very inopportune as well as illegal. Mr. Seward hurried to communicate with Mr. Adams, the United States minister at London, the shrewd suggestion that “in the capture of Messrs. Mason and Slidell on board a British vessel, Captain Wilkes having acted without any instructions from the government, the subject is therefore free from the embarrassment which might have resulted if the act had been especially directed by us.” “I trust,” he wrote, “that the British government will consider the subject in a friendly temper and it may expect the best disposition on the part of this government.”

The penetrating mind of Lincoln had reached the core of the outrage, and the cunning Secretary saw the only way out of the difficulty. Mr. Adams was therefore immediately instructed as to his line of diplomatic work, even before the British government had communicated its indignation to its minister at Washington. But Earl Russell was soon ready to inform Lord Lyons officially that intelligence of a very grave nature had reached her Majesty’s government concerning” an act of violence which was an affront to the British flag and a violation of national law.” The Earl further expressed the trust that the United States will of its own accord offer to the British government such redress as alone could satisfy the British nation, namely, the “liberation of the four gentlemen and their delivery to your Lordship in order that they may again be placed under British protection, and a suitable apology for the aggression which has been committed. Should these terms not be offered by Mr. Seward, you will propose them to him.” It should be borne in mind that the report of the affair made by Commander Williams, the British agent, to the admiralty must be accepted as the unprejudiced account of the events which transpired aboard the “Trent.” With very slight protest Mr. Seward in answer to Lord Russell’s letter admitted the facts to be as stated, and based the defense of his government mainly on the fact that Wilkes acted “without any direction or instruction or even foreknowledge on the part of the United States government.” Upon all grounds, the best course to be pursued was the one suggested kindly and firmly by the English government, but Mr. Seward proceeded to write, after nearly a month’s delay, an elaborate argument ending only as it must have ended, in his repeating that “what has happened has been simply inadvertence,” and that for “this error the British government has the right to expect the same reparation that we as an independent state should expect from Great Britain or from any other friendly nation on a similar case.”

After this explanation and apology, the Secretary concluded his remarkable document by writing that “the four persons in question are now held in military custody at Fort Warren in the State of Massachusetts. They will be cheerfully liberated. Your Lordship will please indicate a time and place for receiving them.” Mr. Seward must have felt the sting that was put in the acceptance of his apology by the English government. That final rejoinder which went through the hands of Lord Lyons to the table of the secretary of state very coolly declared the apology to be full and the British demand complied with. Such pungent sentences as the following appeared in the final British communication: “No condition of any kind is coupled with the liberation of the prisoners” –“The secretary of state expressly forbears to justify the particular act of which her Majesty’s government complained”–and Lord Russell threateningly says that if the United States had sanctioned the action of Wilkes, it “would have become responsible for the original violence and insults of the act”–” It will be desirable that the commanders of the United States cruisers be instructed not to repeat acts for which the British government will have to ask for redress and which the United States government cannot undertake to justify.” The illustrious prisoners were placed under the British protection with as little parade as possible and Captain Wilkes was left to enjoy as best he could the compliments hastily voted by Congress. The Confederate hope that European nations would unite with England in some policy severer than the demand for apology and restitution which Mr. Seward could so easily make was dissipated. The threatening affair produced a ripple, became a mere precedent in national intercourse, and passed away. Lord Russell and Mr. Seward were alike gratified by the termination of the trouble. These upper and nether millstones then went on grinding the Confederacy which lay between.

Source: The Confederate Military History, Volume 1, Chapter XV