About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Before the American Civil War, Abraham Lincoln and other leaders of the anti-slavery Republican Party sought not to abolish slavery but merely to stop its extension into new territories and states in the American West. This policy was unacceptable to most Southern politicians, who believed that the growth of free states would turn the U.S. power structure irrevocably against them. In November 1860, Lincoln’s election as president signaled the secession of seven Southern states and the formation of the Confederate States of America. Shortly after his inauguration in 1861, the Civil War began. Four more Southern states joined the Confederacy, while four border slave states in the upper South remained in the Union.

Lincoln, though he privately detested slavery, responded cautiously to the call by abolitionists for emancipation of all American slaves after the outbreak of the Civil War. As the war dragged on, however, the Republican-dominated federal government began to realize the strategic advantages of emancipation: The liberation of slaves would weaken the Confederacy by depriving it of a major portion of its labor force, which would in turn strengthen the Union by producing an influx of manpower. With 11 Southern states seceded from the Union, there were few pro-slavery congressmen to stand in the way of such an action.

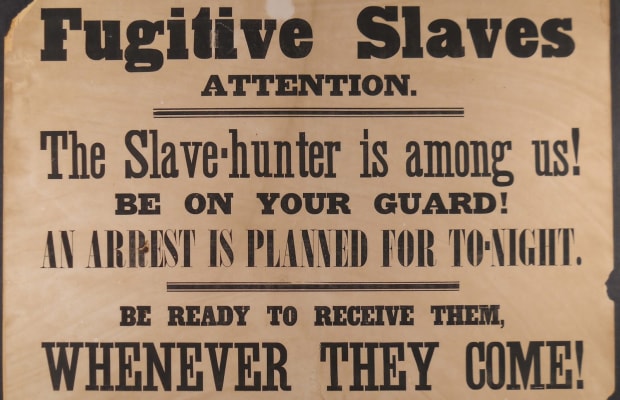

In 1862, Congress annulled the fugitive slave laws, prohibited slavery in the U.S. territories, and authorized Lincoln to employ freed slaves in the army. Following the major Union victory at the Battle of Antietam in September, Lincoln issued a warning of his intent to issue an emancipation proclamation for all states still in rebellion on New Year’s Day.

That day–January 1, 1863–President Lincoln formally issued the Emancipation Proclamation, calling on the Union army to liberate all slaves in states still in rebellion as “an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity.” These three million slaves were declared to be “then, thenceforward, and forever free.” The proclamation exempted the border slave states that remained in the Union and all or parts of three Confederate states controlled by the Union army.

The Emancipation Proclamation transformed the Civil War from a war against secession into a war for “a new birth of freedom,” as Lincoln stated in his Gettysburg Address in 1863. This ideological change discouraged the intervention of France or England on the Confederacy’s behalf and enabled the Union to enlist the 180,000 African American soldiers and sailors who volunteered to fight between January 1, 1863, and the conclusion of the war.

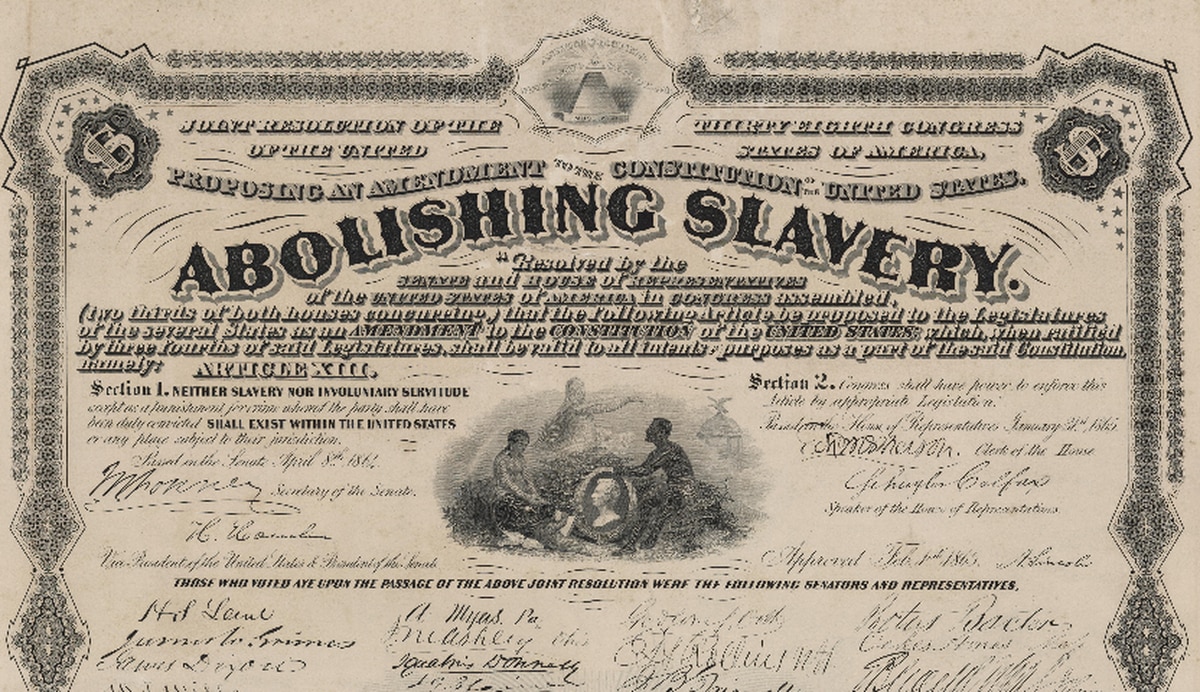

As the Confederacy staggered toward defeat, Lincoln realized that the Emancipation Proclamation, a war measure, might have little constitutional authority once the war was over. The Republican Party subsequently introduced the 13th Amendment into Congress, and in April 1864 the necessary two-thirds of the overwhelmingly Republican Senate passed the amendment. However, the House of Representatives, featuring a higher proportion of Democrats, did not pass the amendment by a two-thirds majority until January 1865, three months before Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

On December 2, 1865, Alabama became the 27th state to ratify the 13th Amendment, thus giving it the requisite three-fourths majority of states’ approval necessary to make it the law of the land. Alabama, a former Confederate state, was forced to ratify the amendment as a condition for re-admission into the Union. On December 18, the 13th Amendment was officially adopted into the Constitution–246 years after the first shipload of captive Africans landed at Jamestown, Virginia, and were bought as slaves.

Slavery’s legacy and efforts to overcome it remain a central issue in U.S. politics, particularly during the post-Civil War Reconstruction era and the African American civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s.