About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Sergeant William Jasper (c. 1750 – Oct. 9, 1779) of the 2nd South Carolina Regiment fought at the Battle of Fort Sullivan, South Carolina, on June 28th, 1776. His daring and courageous action that day was recorded by those present, later subjected to the romantic pen of 19th century historians. Like many who fought in militias, Sergeant Jasper’s spell as a soldier ended when his term of enlistment expired. As the war intensified, he re-enlisted his services in a special commission that encompassed hit and run guerilla type tactics against British and loyalist troops; again his feats were dramatized in elaborate historical texts. On October 9th, during the failed American attempt to take Savannah, Sergeant Jasper was mortally wounded while rallying the troops around the colors. He was able to retain his regimental colors during the retreat and died shortly after.

Colonel William Moultire, victorious commander of Fort Sullivan, praised Sergeant Jasper’s bravery during the battle. Soon afterwards Governor John Rutledge, during a ceremony giving thanks to the Sullivan Island garrison, presented his personal sword to Jasper. Colonel Moultire wrote in his memoirs, “The same day, a number of our friends and fellow citizens came to congratulate us on our victory and Governor Rutledge presented Sergeant Jasper with a sword, for his gallant behavior…” Evidence of this can be found in the South Carolina treasury records indicating seventy pounds paid to replace the governor’s sword for the one Rutledge gave to Jasper. This established the sergeant’s place in history and aroused joyous Carolina patriots to toast the garrison’s and Jasper’s heroics, now known as Carolina Day.

After the British abandoned Boston on March 17, 1776 for Halifax Canada, plans were put in place to reassert British rule over the colonies. A massive armada was to invade New York City while another, lesser fleet would sail to Charles Town, South Carolina, to establish British jurisdiction over the south. The assault by combined British naval and military forces under the command of Admiral Sir Peter Parker and General Henry Clinton would attack Fort Sullivan that guarded the harbor to the city. Once the fort was subdued by Admiral Parker’s fleet, General Clinton would land his forces and seize Charles Town, at the time the fourth largest and the wealthiest city in British North America. Word of the intended invasion spread and American General Charles Lee, second in command to General Washington, was sent to Charles Town to help with the city’s defense. He arrived shortly before the British fleet entered the harbor.

Local Carolina residents had already responded to the threat by strengthening Fort Sullivan. Palmetto logs were laid into the partially completed fort which proved to be a blessing. Though General Lee recommended that the fort be abandoned, Colonel William Moultrie and Colonel William Thomson, who commanded militia from South and North Carolina, including some native and African Americans, refused and remained to fight. On June 28th, British frigates anchored before the fort and bombarded the garrison’s wall with twenty four and thirty two pound shot and explosive shells. It was soon discovered that the tough, pliable palmetto logs dampened the initial blow by absorbing the shot and thereby lessening the damage. The Americans slowly and purposely aimed their big guns at the anchored ships and poured shot after shot into the ships’ hulls. The devastation to the British fleet was so destructive, with massive casualties, that Admiral Parker had no choice but to withdraw his frigates and bomb ketches. This spectacular victory over the might of the British Empire dampened England’s hopes for quickly subduing the rebellion in the American colonies while greatly strengthening the patriot resolve for independence.

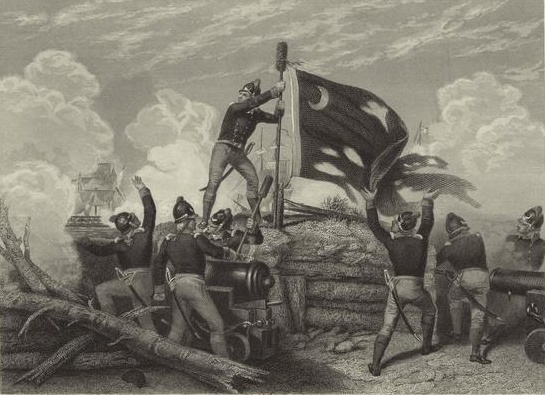

During the battle, the fort’s flag was shot away and fell outside the fort, accordingly disheartening both the soldiers fighting behind the fort and the citizens of Charles Town lining the harbor to observe the battle. Many within the town assumed that the colors were beginning to be drawn down prior to the garrison’s surrender. Soon after, the flag once more reappeared fluttering over the fort’s rim, reviving the defenders spirits. Sergeant Jasper had leapt up from behind the fort’s wall and retrieved the flag. He fixed it to a sponge staff used to clean cannon bores after firing and set it atop of the fort, “our flag once more waving in the air, reviving the drooping spirits,” wrote Colonel Moultrie. Here is Colonel Moultrie’s description of the event: “After some time our flag was shot away; their [citizens of Charleston] hopes were then gone, and they gave up all for lost! Supposing that we had struck our flag, and had given up the fort, Sergeant Jasper perceiving that the flag was shot away and had fallen without the fort, jumped from one of the embrasures, and brought it up through a heavy fire, fixed it upon a sponge-staff, and planted it upon the ramparts again. Our flag once more waving in the air revived the drooping spirits of our friends…”

The flag that Jasper rescued and planted on Fort Sullivan’s rampart, referred to as the Moultrie Flag, was not the stars and stripes, mistakenly depicted in some historical texts and internet articles. In 1775, at the start of hostilities between the colonies and England, the South Carolina Revolutionary Council of Safety requested Colonel William Moultrie, the leading military expert in the providence, to design a banner for the use of South Carolina State Troops (militia). Accordingly he chose a blue background for the flag that matched the color of the troops’ uniforms. He also selected a crescent that reproduced the silver emblem worn on the front of the soldiers’ caps. There has been some debate as if the crescent was symbolic of the moon, or of a gorget – metal crescent, left over from the days of armor, worn around the neck of officers throughout Europe and adopted by military officers in the colonies.

Most images of the Moultrie Flag supposedly flown above Fort Sullivan during the battle had the word Liberty etched into it. Moultrie does not mention the use of the word Liberty in his description of the flag nor could this writer find another primary source that does. The Moultrie Flag, with one addition, has become South Carolina’s state flag. The Sabal Palmetto tree was added in 1861 after South Carolina ceded from the Union.

William Jasper’s heroics at Fort Sullivan were lavishly elaborated upon by 19th century authors which became the basis for later historical texts and articles. One of the more fanciful versions was written by Mason Locke Weems, who gave us the tale of George Washington cutting down his father’s favorite cherry tree in his popular 1800 novel “Life of Washington”. He wrote of Jasper in 1805: “Scarcely had the stars of Liberty [as noted, it was not the stars and stripes, but the S. Carolina flag of crescent on a solid blue background] touched the sand, before Jasper flew and snatched them up and kissed with great enthusiasm. Then having fixed them to the point of his spontoon [not a spontoon, but a sponge rod used to clean out cannon after firing] he leaped up on the breast work amidst the storm and fury of battle, and restored them to their daring station – waving his hat at the same time and huzzaing “God save liberty and my country forever!”

This last bit of huzzahing by Jasper was the first publication of this – not found in any primary sources, and has since been repeated many times in later accounts of Jasper’s actions that day. Weems also had a hand in the ceremony after the battle was won writing that after Governor Rutledge presented his sword to Jasper, he supposedly offered the sergeant a commission which Jasper nobly and rather humbly turned down, “I am greatly obliged to you governor…but I had rather not have a commission…I pass very well with such company as a poor sergeant has any right to keep…”

Little definitively is known of Jasper prior to and during his military service. An examination of texts and internet articles on William Jasper will only confuse the matter by presenting several contrary narrations of his early life. One account that pops up frequently states that Johann Wilheim Gaspe, of German descent, arrived in Philadelphia, around age 16, in 1767 aboard the ship Minerva. Upon arrival, he was listed as John William Jasper. He began a period of indentured servitude supposedly to assist in paying for his passage to America. He remained in Philadelphia for a few years before moving south to purchase land. Once established in Georgia, he sent for his future wife Elizabeth from Philadelphia and began raising a family when the war broke out. Another narration proclaims that William Jasper was born on September 11, 1757 in Cooper River, South Carolina. That he married Mary Wheatley of Pennsylvania in 1776. Several other assertions reveal his birth in Georgia, Virginia, North Carolina, Ireland, England, and Wales. Examinging recent genealogy searches suggest that perhaps William Jasper was mixed up among members of an extended Jasper family, assigning William Jasper’s birth, marriage, and children to the wrong sibling or ancestor. At the time of the Fort Sullivan Battle, it is estimated that Jasper’s age was anywhere from twenty five to thirty years.

Nic Butler, publisher of the Charleston Time Machine through the Charleston County Public Library, wrote an interesting article on June 22, Who Was Sergeant Jasper. While sifting through the Charleston Archives at CCPL, he came across surviving records of the Charleston Poor House (renamed the Alms House in 1856). He found numerous references to a destitute widow by the name of Elizabeth Brown. Mrs. Brown came to the Poor House in the summer of 1836 to apply for rations. She lived alone and began visiting the Poor House three times weekly to receive her city-funded rations. She became well known at the House and no doubt discussed her history with staff, mentioning her famous father. Word spread and in a report published in the Southern Patriot in 1837, Elizabeth Brown was described as “a resident and a native of Charleston.”

According to Ms. Brown’s conversation with the reporter, her father, William Jasper, was a native of Ireland who was “about 45 years of age” at the time of his death in 1779 (at the Battle of Savannah). He had “married a lady in the interior of this state.” A year later, a petition was presented to the U. S. House of Representatives to grant Mrs. Elizabeth Brown, daughter of Sergeant William Jasper, “who gallantly fell at the Battle of Savannah, after rendering the most important service to his country.” The request was denied. Six years later, a petition was filed in the State House by Henry Laurens Pinckney on behalf of Ms. Brown. It was approved and on December 18, 1844, “An Act to Grant a Pension to Elizabeth Brown” was presented to the financial strapped widow. She enjoyed the $100 annual pension but for one year, dying at age 70 in November of 1845.

Elizabeth Brown would have been born around 1775. Sergeant Jasper was not killed in battle until four years later so it is quite possible that she could have been his daughter. However, it is reported that William Jasper had a brother Nicholas who married an Elizabeth who had a daughter named Elizabeth. Could Mrs. Brown have been Nicholas’s daughter instead of William’s, hoping to better her later years in life by claiming her uncle was her father and petitioning for the uncle’s war pension? “Nicholas Jasper, a soldier of the Revolution…was the son of John Abraham Jasper who is said to have been born in 1728 at Cavermathren, Wales. He married Mary Herndon and settled near Georgetown, South Carolina in 1748, later moving to the Cooper River and near Charlestown in 1752 where they reared their family of four sons and three daughters. Nicholas and his brothers John and William served under General Francis Marion and General William Richardson Davie [William served under Colonel Moultrie] in North and South Carolina and Georgia. William was the hero of the battle of Fort Moultrie [Fort Sullivan during the battle], June 17, 1776 [June 28, 1776], and was killed in the assault on Savannah, October 7, 1779 [October 9, 1779]… Nicholas married Elizabeth Wyatt and to this union was born Elizabeth…”

Jasper remained with the militia until sometime in 1778, receiving his discharge. According to a letter from Major General Benjamin Lincoln at Charlestown (commander of the southern theatre), dated July 18, 1779, Jasper is recommended to Colonel Moultrie and requested that he put Jasper and a “party of men” to good use. “Sergeant Jasper with a party of men wait upon you, desirous of something being given them to do. Your being immediately on the spot, will better able you to judge of the most advantageous man in which they may be disposed of. It is thus my wish that they may be employed at your discretion.” Colonel Moultrie gave Jasper what amounted to a “roving commission”. He wrote back, “The business here, to my opinion, will be only to wait on the motions of the enemy…I have sent the Georgia troops, and have also detached Captain Newman’s company of horse, and Jasper’s little party, to harass and perplex the enemy in that state. I have given them directions to join Colonel John Dooley.”

Years later, Moultrie wrote in length in his memoirs of Jasper’s qualities and his use of him and his ‘small party’ to harass the enemy. “At the commencement of the war, William Jasper entered into my regiment, [2nd S. Carolina State Troops] and was made a sergeant; he was a brave, active, stout, strong, enterprising man, and a very great partisan. I had such confidence in him, that when I was in the field, I gave him a roving commission, and liberty to pick out his men from my brigade, he seldom would take more than six: he went often out, and returned with prisoners before I knew he was gone. I have known of his catching a party that was looking for him. He has told me that he could have killed single men several times, but he would not, he would rather let them get off. He went into the British lines at Savannah, and delivered himself up as a deserter, complaining at the same time, of our ill usage to him, he was gladly received (they having heard of his character) and caressed by them. He stayed eight days, and after informing himself well of their strength, situation and intentions, he returned to us again; but that game he could not play a second time. With his little party he was always hovering about the enemy’s camp, and was frequently bringing in prisoners.”

In 1805, Parson Weem’s inventive pen immortalized Francis Marion and so too Sergeant Jasper. He devoted all of chapter two to Jasper and fellow guerilla warrior John Newton. Since so little was recorded about Jasper’s role in the war outside the memoirs of Colonel Moultrie, much of what Weems wrote was drawn from his imagination. He told tales of daring escapes, artful deceptions, chivalry while fearlessly rescuing damsels in distress and American prisoners from British steel. His feats were the stuff of super heroes of today’s media and the foundation of historical fiction novels. Even though some historical truths were woven between the lavish and elaborate descriptions, the books came at a time when much of America was still being settled. After Weem’s novel The Life of Francis Marion appeared on book shelves, dozens of towns and counties were named for Jasper and Newport. It seems the American public eagerly accepted Weem’s fantastic tales and glamorous adventures of the two daring patriots as fact.

In 1779, Jasper fell at what has been called the Second Battle of Savannah; the American’s failed in this attempt to take back Savannah from the British. The British had captured Savannah the year before. From September 16th to October 18th, 1779, French and American forces stage what amounted to a siege to retake the city. On October 9th, a major assault against the British works failed. During this attack, Jasper and many of his fellow soldiers was killed. This battle was noteworthy as it was one of the most significant joint efforts of American and French forces in the war. What is also of interest is that a French colonial force of five hundred recruits from Saint Domingue (present Haiti) joined in the American siege. many “soldiers of color” and black slaves had been established to join the American effort. After the Oct. 9th failure, the siege was abandoned and the British remained in control of Savannah until July 1782.

Colonel Moultrie describes Jasper’s last moments, “…Lieutenants Hume and Bush planted the colors of the 2nd South Carolina regiment upon the ramparts, but they were soon killed. Lt. Grey was on the ramparts, near the colors, and received his mortal wound; the gallant Jasper was with them, and supported one of the colors, until he received his death wound, however he brought off one of the colors with him, and died in a little time after…Three lieutenants and Sergeant Jasper, killed in supporting the colors on the rampart.” Many historical texts state that Jasper owned the flag he carried into battle. There may be some truth to Pastor Weem’s elaborate account as to how Jasper obtained the colors he died while saving the flag after the retreat was sounded. Weems wrote about the ceremony after the Battle of Sullivan Island, claiming that besides the governor’s sword, Sergeant Jasper was also given the state’s colors. “…a most superb pair of colors, embroidered with gold and silver by her own lily-white hands [described by Weems as Mrs. Colonel Elliot of the artillery]. They were delivered I mistake not to the brave sergeant Jasper, who smiled when he took them, and vowed he “would never give them up but with his life.” Though one could question his gallant words spoken that day, history cannot deny that he kept his word.

After Jasper was killed he, along with many who died during the October 9th, 1779 assault, was buried in a common, unmarked grave outside Savannah. A statue was commissioned in 1888 that featured William Jasper’s courageous act on June 28th, 1776. It was designed by Alexander Doyle, famous Civil War artist who was responsible for many of the statues dedicated to Confederate leaders of the war. The statue sits in Madison Square, Savannah, Georgia, just a few yards northwest from the British line and where Jasper fell.

The U.S. mint’s America the Beautiful Quarter Program’s 2016 quarter features Jasper holding the South Carolina flag over Fort Sullivan. As previously stated, many towns and counties were named Jasper after this dedicated Revolutionary War soldier. His sacrifice is honored annually with the Sergeant William Jasper Memorial Ceremony, which includes a wreath laying at the monument.