About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

The causes which made possible the assertion of American National Independence must be sought, not merely in the oppressive legislation which directly provoked the colonists into revolt, but, back of that, in the political institutions they had evolved for themselves; in the self-dependence made necessary by the distance and indifference of the mother country; in the inherited instinct for self-government common to all of the English race; in their desire for commercial and territorial expansion, and in the occasional and temporary unity of action to which they were from time to time forced for mutual defense against a common enemy.

When the struggle which ended in the Revolution began, the thirteen colonies were pretty much representative democracies. All of them elected legislatures, which made laws, laid taxes, levied troops, provided for grants, and formed a real government of the people by the people. Two of the colonies, Connecticut and Rhode Island, held charters which allowed them to choose their own Governors as well. So complete were these two charter-grants that when the Union was formed no change was needed in the political structure of the two States; and, in fact, no change was made for many years. Massachusetts originally held an equally liberal charter, but was deprived of it by an arbitrary act of the Crown, as we shall see. Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland were still proprietary colonies, but through self-interest the nominal proprietors granted a large measure of self-government. The other colonies had elective legislatures, but in each the Royal Governor had an absolute veto power over legislation. In all the bond to the English Crown was the charter or royal grant. Naturally, the colonists construed these grants very strictly, confining the power of the Governor to the closest legal construction of the charter, and assuming for themselves every power not specifically withheld. Above all, the colonists well understood the immense advantage that their power to grant or withhold supplies of money gave them. In reality, government in local matters practically rested with the Assemblies. The Royal Governors might, and did, fume and fret, complain to the English Government, and denounce their subjects as turbulent and obstinate, but they were met by passive resistance and, in more than one case, by actual force.

Looking more closely into the political structure of the colonies, we find in New England, in full swing, the purest democracy the world has ever known, in the town-meeting system. In these town meetings every citizen had his right to speak and his vote, and the meeting assumed the fullest authority over all local matters, forming, also, the unit for legislative representation. In the Southern colonies the county took the place of the New England town as the political unit, but here, also, the democratic idea had taken strong hold. Massachusetts and Virginia were by far the most advanced examples of these two types of local government. As might naturally be expected, therefore, we find them always in the lead in resenting arbitrary actions of the Royal Governors and of the Crown. They were not only the largest and oldest of the colonies, but their peoples were far the most homogeneous. In each the population was almost wholly English, and in large part was made up of the third and fourth generations of the original settlers. Differing as widely as possible in origin the one people coming mainly from the Roundheads, the other largely from the Cavaliers; differing widely, also, in social and religious matters and in habits the one being austere and simple in life, the other almost aristocratic;—yet each had unified, had become distinctly American, and was free from close dependence on the mother country.

Massachusetts and Virginia had also in common the bitter recollection of actual conflict with the royal authority. In Virginia Bacon’s Rebellion had left the seeds of discontent. It originated in the wish of the Virginia colonists to put down Indian disturbances without waiting for the tardy action of the Governor. Nathaniel Bacon boldly led his neighbors to an attack on these Indians without due authority from Governor Berkeley, who had promised him a commission, but had failed in this and other promises of assistance to the distressed colonists. Berkeley forthwith proclaimed Bacon a rebel, and war on a small scale ensued and continued until the latter’s sudden death. Massachusetts had a still more irritating memory in the Andros tyranny and the loss of her charter. When Charles the Second mounted the throne his resentment at the Puritan sympathies of New England led him to lend a willing ear to various complaints against the province; his commissioners were refused recognition by the General Court of the colony, which “pleaded his Majesty’s charter;” the controversy became so intense that it is recorded that in 1671 the colony was “almost on the brink of renouncing its dependence on the Crown;” finally in 1684 the charter was declared forfeited by the English Court of Chancery, and Sir Edmund Andros was sent out as “President of New England,” a new and quite unconstitutional office. Connecticut, as every school-boy knows, saved her charter by hiding it in the historic oak tree; Massachusetts was less fortunate, and something very like anarchy followed until the news came of the beginning of the reign of William and Mary, when Sir Edmund was seized and thrown into prison, and an assembly of representatives at Boston provisionally resumed the old charter. In the end the colony was forced to accept a new charter by which a Royal Governor was granted a veto power. But Massachusetts never forgot her old and more perfect form of liberty, and never was as well disposed as before to the Crown.

The colonies of New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and the Carolinas were in population comparatively mixed, were less unified; and in them, therefore, we find, when the Revolution begins, a strong Tory element, which made their action uncertain and often reluctant. Generally speaking, the Royal Governors of the colonies were not in sympathy with the peoples; they were usually arrogant, sometimes mere adventurers, often weak and vacillating. Their quarrels with the Assemblies usually turned on grants of money. And here, even in early times, we find everywhere cropping up the principle which later was voiced in the watchword of the Revolution, “No taxation without representation.” It has been said that this watchword was illogical; that in point of fact not all people in England who were taxed were represented in Parliament, and that, on the other hand, the American colonies had no real wish for representation in Parliament. Both statements are true, but the representation demanded by the Americans was that which they already had—that of their own legislatures. The idea was succinctly expressed as far back as 1728, when the Massachusetts General Court refused to grant a fixed salary for Governor Burnet because it is the undoubted right of all Englishmen, by Magna Charta, to “raise and dispose of money for the public service, of their own free accord without compulsion.” And the converse of it was seen in Pennsylvania when, the Governor having refused his assent to a bill containing a scheme of taxation, the Assembly demanded his assent as a right. The doctrine, in short, was simply that money raised from the people should be expended by the people, that the Assemblies were the legal representatives of the people, and that they, and they only, could know what taxes the people could bear and how the sums thus raised could be expended to public advantage. The expression of this theory varied continually up to the Declaration of Independence, but its substance was consistently maintained. From the position that parliament had no right to interfere in internal taxation the colonies in the end advanced to the position that their allegiance was to the Crown; that the parliament was in no sense an Imperial Parliament; that the Crown stood for English rule over all British dominions; but that while the laws of England were to be enacted by the English parliament, the laws of the American colonies were to be formulated by their own representatives in legislatures assembled. It was only as a last resort and when driven to extremity that the colonies threw off that loyal allegiance to the Crown which they had held to be quite consistent with the maintenance of this basic principle of their liberties.

Let us look now for a moment at the imperfect and temporary union entered into from time to time by the colonists for mutual defense, and which in a way foreshadowed the greater and permanent union of the future. Along the coast the English power had become continuous; the Dutch power at New Amsterdam had been swept away; the Spaniards had been pushed back to the South; the Indians and the French were held at bay on the West and North. In King Philip’s War the New England colonies had combined to raise two thousand troops and had conquered by concerted action. In the early French and Indian wars military operations had also been carried on in concert by the colonies with varying successes. Thus, the New England colonies and New York had captured Port Royal in 1690, and had even attempted an attack on Quebec, and in 1709 and 1712 expeditions were planned against Canada and Acadia, in which the colonies united. Both of these latter comparative failures led, by the way, to the issue of paper money to cancel the heavy debts incurred. When Great Britain was at war with Spain the Southern colonies Georgia, Carolina and Virginia had also united in an unsuccessful expedition led by Oglethorpe against Florida. In King George’s War the colonies planned and carried out almost without help from England the expedition by which the French stronghold Louisburg was seized. Encouraged by this notable triumph of their four thousand troops, they projected the conquest of Canada an undertaking so vast that it is not surprising that it was soon abandoned.

But the most serious emergency arose when France and England were for a short time at peace, after the treaty of Aix-La-Chapelle (1748). The French plan of extension of territory in America was one of unbounded ambition and of unity of purpose. From New Orleans to Quebec the French had gradually erected a line of fortified posts along the course of the explorations of La Salle, Joliet, Marquet and D’Iberville. Following their theory that the discoverers of a river were entitled to all the territory drained by it, they were occupying the Mississippi valley and were moving eastward toward the Alleghanies, thus drawing close round the English territory and threatening to invade it. Fortunately their line of outposts from Quebec to New Orleans was only as strong as its weakest part; otherwise English supremacy on the Continent would have been overthrown. With their Indian allies the French were now face to face with the pioneers of the colonies who were pressing westward, and who on their side were strengthened by the Indian alliance of the Six Nations. The Ohio Company had been formed for the purpose of colonizing the valley of the Ohio River and to check the progress of the French eastward. It was believed that the territory of the company was infringed upon by French settlements, and George Washington, then a young surveyor, was sent by Governor Dinwiddie, of Virginia, to examine the actual condition of affairs on the frontier. The wily French gave him fair words but no satisfaction. In this, Washington’s first service to the country, he showed on a small scale the calmness, firmness and courage that made him a few years later the hope and support of a nation. His report on the frontier situation was so serious that the colonists determined on immediate war and Virginia called the other provinces to her aid. How to raise men and money was a serious question. It was to solve the difficulty of conducting the campaign that Benjamin Franklin proposed, at a meeting of commissioners of the several colonies held at Albany, a plan of confederation, commonly called the Albany Plan. It provided for a form of federal government which should not interfere with the internal affairs of any colony but should have supreme power in matters of mutual defense and in whatever concerned the colonies as a body. The Albany Plan included a President or Governor-General who should be appointed and paid by the King, and a Grand Council to be made up of delegates elected once in three years by the colonial legislatures. This scheme found favor neither with the Crown nor with the colonial assemblies; each party considered that too much power was given the other, and the colonies also objected to accepting taxes imposed upon them by a body in a sense foreign to each though composed of delegates from all. Yet the project is of immense interest and significance, historically, because it shows in what way men’s minds were turning and how the leaven of National unity was working almost without the knowledge of the people themselves.

The war that ensued was at first carried on in America alone, though after two years it became a part of the great Seven Years War between France and England (1755-63). At the outset the key of the territorial struggle lay at the junction of the Alleghany and Monongahela rivers, near where Pittsburgh now stands. Here Washington was besieged in Fort Necessity and was compelled to capitulate by overwhelming forces, but under honorable conditions. The French still held Fort Du Quesne, and against this Braddock’s unfortunate expedition was directed. Now at last the colonists were dispossessed of their old idea of the invincibility of British troops. The regulars, disregarding the advice of the Americans, who understood Indian and French warfare, fell into an ambuscade and were all but cut to pieces. The lesson must have been a startling one to the untrained, half-armed provincial troops. As one writer has said, ” The provincial who had stood his ground, firing from behind trees and stumps, while the regulars ran past him in headlong retreat, came home with a sense of his own innate superiority which was sure to bring its results.” Thus and in many other ways throughout the war the Americans learned their own possibilities as soldiers on their own ground. The details of the war need not here be reviewed. With the great battle on the Plains of Abraham and the death of the heroic Wolfe and the not less intrepid Montcalm, French dominion in the new world perished forever. It is well known that the mortification of the French statesmen was allayed by the astute reflection that the now undisputed power of Great Britain was likely to be but temporary. Said the Duke de Choiseul, “Well, so we are gone; it will be England’s turn next.” He saw and other French statesmen predicted the same thing that the very fact that no external enemies threatened the provinces would bring them face to face with the mother country for the final struggle.

Indeed, the treaty of Paris was not even signed when the mutterings of the storm were heard. Now, thought England, was the time to enforce her disregarded authority; now, thought the colonies, was the time to insist on their rights of expansion and of self-government. England’s whole theory of the relation of colonies was radically wrong, though she held it in common with other great Powers. This theory was that the colony was merely a commercial dependency —a place where the mother country could extend its trade; while by no means was the colony to be allowed to compete in trade at home or in the world’s markets. To this end had been enacted years before the so-called Navigation Laws. By these Americans were forbidden to export their products to other countries than England, to buy the products of other countries except from English traders, to manufacture goods which could compete in the colonies with English importations (for instance, there was even a law against the making of hats), or to ship goods from colony to colony except in British vessels; while a high protective tariff prevented the colonists from selling grain and other raw products to England. A peculiarly ingenious and annoying repressive measure was that known as the Molasses Act, aimed to stop that extensive trade which consisted in taking dried fish to the French West Indies, receiving molasses in return, bringing it to New England, there turning it into rum, and finally, taking the rum to Africa, where it was often traded for slaves, who in turn were usually sold again in the West Indies. The Molasses Act insisted that the Yankee traders should carry their fish only to the British West Indies; and as these islands did not wish the fish there was an end, theoretically, to a very profitable if not altogether moral system.

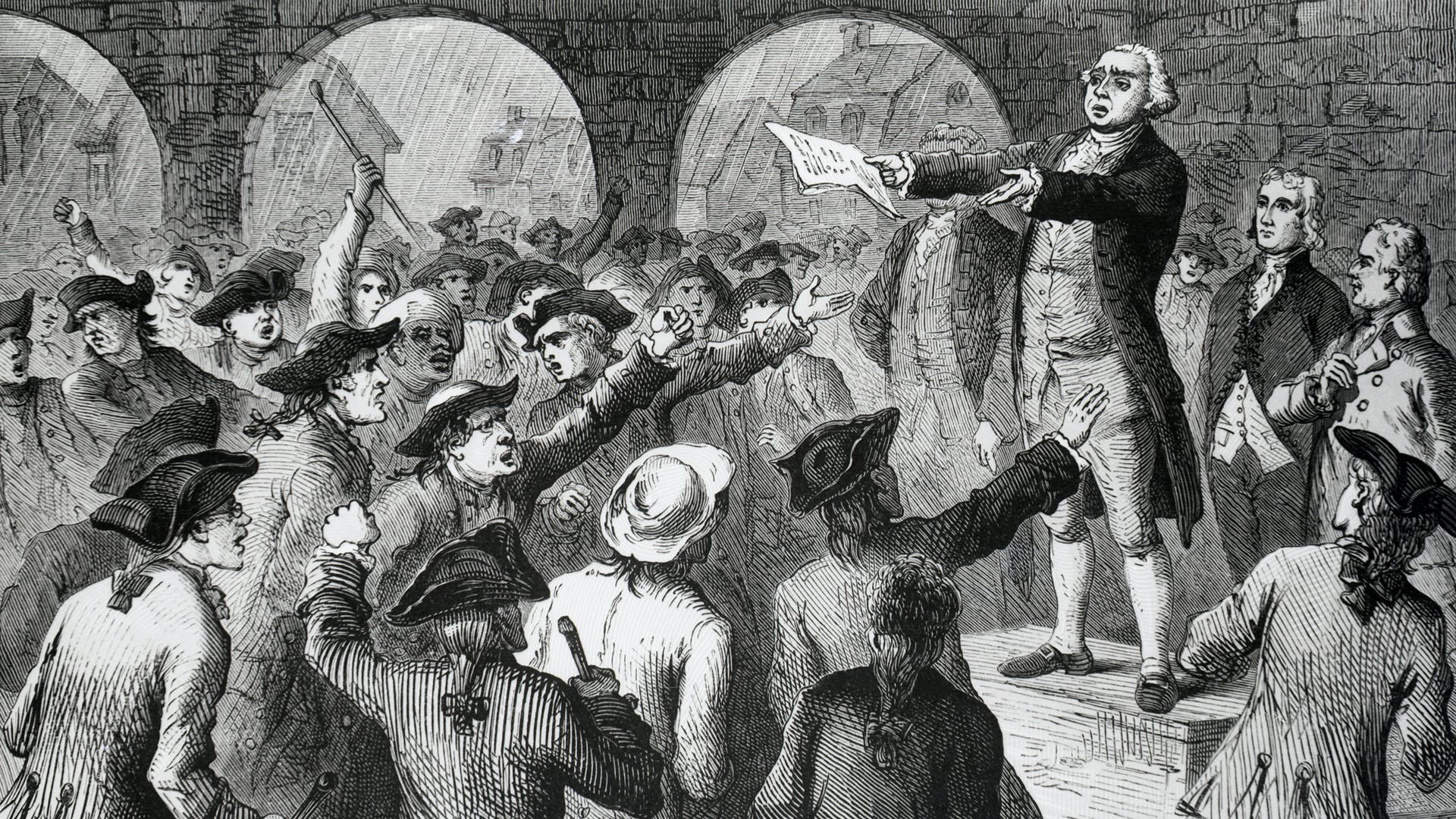

In point of fact, all these laws had been constantly disregarded; smuggling and surreptitious trading were universal. But now it was suddenly attempted to enforce them, and that by the obnoxious Writs of Assistance search warrants made out in blank, so that they could be filled out and used by any officer, against any person, at any time. This was quite contrary to the spirit of the English law, and met with such a sturdy resistance that, though the courts did not dare to declare the writs illegal, the practice was abandoned. James Otis, in particular, thundered against the Writs of Assistance (rather than to defend which he had thrown up his office as King’s Prosecutor) in a speech at the utterance of which John Adams declared ” the child, Independence, was born.” Almost simultaneously with this excitement in Boston, Patrick Henry was delivering his maiden speech in Virginia against the royal veto of a bill diminishing the salaries of the clergy. He denounced any interference with Virginia’s law-making power, and boldly proclaimed that when a monarch so acted he ” from being the father of his people degenerated into a tyrant, and forfeits all rights to obedience.”

While yet the bickering about the old laws continued, a quite novel form of taxation was rushed through Parliament, “with less opposition than a turnpike bill.” The Stamp Act was indeed a firebrand such as its originators little suspected. Great Britain had been at great expense during the recent wars, and naturally thought that the Colonies should bear their share of the cost. On their side, the Colonies maintained that they had done all that with their feeble means was possible. George III had lately (1760) mounted the throne. He was narrow-minded, obstinate, a thorough believer in kingly authority; and, as he could not strive for personal supremacy by the means which proved so fatal to Charles I, he adopted the methods of wholesale political bribery, of continual intrigue, and of relentless partisan enmity to those who opposed him. It was because these opponents of his, or some of them, sympathized with America that he grew fixed in his determination to exact obedience. He hated the liberty-loving Colonists chiefly because he hated the New Whigs in England. His minister, Grenville, thought to please his royal master, and at the same time not to offend beyond endurance the Americans, by his invention of the Stamp Act.

This ordered that in the Colonies all contracts, legal papers, wills, real-estate transfers, as well as newspapers, should be printed on stamped paper, or on paper to which stamps had been affixed. Coincident with it was passed a law ordering the colonial assemblies to support in various ways the royal troops which should be sent to them. So that this whole scheme proposed, first, to tax the Colonies illegally (as they held), then to send soldiers among them to enforce the tax, and, finally, to compel them to pay for the support of these very soldiers. No wonder that a storm of indignation raged from Maine to Georgia. Grenville himself was amazed at the result. In Massachusetts Samuel Adams declared that this was violating the liberty of self-government, to which subjects in America were entitled to the same extent as subjects in Britain. Patrick Henry, in Virginia, presented resolutions declaring that, ” The taxation of the people by themselves or by persons chosen by themselves to represent them, who can only know what taxes the people are able to bear, is the distinguishing characteristic of British freedom,” and that the General Assembly of Virginia, therefore, had the sole and exclusive right and power to lay taxes upon the inhabitants of the Colony. A congress of delegates from nine of the Colonies soon met at New York and set forth the same principle of Colonial rights in a petition to the Crown. No attempt was made by this Stamp Act Congress to do more than declare the feelings of the united Colonies. But it was a distinct advance in the direction of union. Meanwhile, the people at large showed a disposition to take the matter in their own hands, without regard to Parliament or Congress, or lawyers, or fine spun theories of constitutional right. When the stamps arrived they were burned or thrown into the sea; stamp officers were compelled to resign their offices; mobs in a few cases injured the property of obnoxious persons; the “Sons of Liberty” formed themselves into clubs and warned all to “touch not the unclean thing” under penalty of mob law. When the time came for the Stamp Act to go into operation there were no stamp officers to enforce it. One of them has left it on record that when he rode into Hartford to deposit his resignation, with a thousand armed farmers at his heels, he felt “like Death on the pale horse With all hell following him.” No doubt there were some acts of mob law at this time which a strict sense of justice could not approve, but, as Macaulay has said, “the cure for the evils of liberty is more liberty;” and so, in the end, it proved in this case.

On May 16th, 1766, a Boston paper published what we should call today an “extra,” in which, under the heading “Glorious News,” it reported the arrival of a vessel belonging to John Hancock, with news of the repeal of the Stamp Act. Grenville’s Ministry had fallen, and with it fell his measure. Rejoicings in London were, the paper stated, general. Ships in the river had displayed all their colors, and illuminations and bonfires were going on all over the city. This shows how widespread at that time was the English sympathy for Americans; even during the war it was not wholly suppressed. The “extra” from which we have quoted ends its account by saying, “It is impossible to express the joy the town is now in, on receiving the above great, glorious, and important news. The bells in all the churches were immediately set a ringing, and we hear the day for a general rejoicing will be the beginning of next week.”

But even this change of front on the part of Parliament was accompanied by a gratuitous declaration to the effect that it had the power ” \to bind the colonies and people of America in all cases whatsoever.”

Lord Rockingham’s Ministry, which had repealed the futile and fruitless Stamp Act, lasted but a year; it was followed by that of which the Duke of Grafton was nominally the head, but in which the unscrupulous and audacious Lord Townshend, the Chancellor of the Exchequer was the real leader. He at once proposed and carried a law imposing on the American Colonies import taxes on glass, paper, painters’ colors, lead and tea. To such laws as this, he cunningly argued, the Colonies had often before submitted. In a way they submitted to this also; that is to say, they did not at first resist its constitutionality, but retorted by entering into “non-importation” agreements, by which they bound themselves as individuals not to purchase the taxed articles. Merchants who persisted in selling the obnoxious goods were boycotted, as we call it now, and found placards posted up in which it was demanded that to quote one of these notices literally “the Sons and Daughters of Liberty would not buy any one thing of him, for in so doing they will bring Disgrace upon themselves and their Posterity, for ever and ever, AMEN.” It was not denied that it was the intention to use the sums raised by these taxes to pay the salaries of the royal governors and of the colonial judges, and to maintain British troops in the colonies. This was emphatically subversive of free government. New York refused to make provision for troops quartered upon it, and only consented tardily and imperfectly when its legislature was, as a penalty, suspended by the Crown. Massachusetts threw all kinds of technical legal obstructions in the way of providing for the two British regiments which arrived at Boston. Protests against the Townshend Act made in an orderly meeting in Boston were denounced in Great Britain as treasonable, and it was proposed that colonists guilty of such offenses should be brought to England and there tried for treason. If anything were needed to inflame still further the colonists’ indignation it was this. Massachusetts sent out a circular letter to other colonies asking them to unite in petitions and remonstrances to the king; this in turn was treated as also treasonable; a disturbance caused by the seizure of a sloop belonging to John Hancock for customs’ offenses was magnified into a riot; the dreaded act providing for the trial of accused colonists in England was passed; in every way the situation was becoming critical.

The presence of the British troops in Boston was irritating in the extreme to the masses of the citizens; quarreling between soldiers and citizens of the rougher class was constantly going on, and finally in March, 1770, a street brawl ended in the so-called Boston Massacre, when the troops, not without very great provocation, fired upon the citizens, killing five and wounding six. From that day the hearts of the common people were ready for armed resistance at any minute. Looking back on the “massacre” from the cool standpoint of history, it must be admitted that it was not quite the merciless and causeless act of brutality which it seemed then to the inflamed minds of the populace, but its influence at the time was enormous.

The year of the Boston Massacre saw also the accession of the subservient Lord North as the Prime Minister and tool of George III. With him began a new chapter in the attempt to enforce taxation without representation. The non-importation pledges were beginning to fall into disuse, and Lord North was led to hope that by removing all the taxes except that on tea the colonists would yield the point of principle involved. George III himself had said, “I am clear there must always be one tax to keep up the right,” and it was thought that the three pence per pound would be regarded as a trifle not worth fighting for. But the colonists were not fighting for money but for a principle; and in 1772 it was found that the tea tax was yielding only $400 a year, while it was costing over a million of dollars to collect it. A last cunning trick was attempted by Lord North; he gave the East India Company a rebate on teas taken to America, thus making it possible for the colonists to buy the tea with the threepenny tax still on it and yet pay less than before the tax was laid. It is to the honor of our forefathers that the subterfuge was instantly detected and the new proposal resented as the deepest insult. Cargoes of tea were sent to Charleston, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. In the first city the tea was stored in damp cellars and purposely spoiled; New York and Philadelphia refused to allow the tea to be landed; Boston held her famous tea party; and in still other ports the tea was burned.

The destruction of the tea in Boston harbor was not one of those mob acts (like the brawl which led to the Boston Massacre, or the burning of the revenue schooner “Gaspe” in Rhode Island) which are the inevitable but regrettable accompaniments of a great popular movement; it was rather a deliberate act, agreed on by the wisest leaders and carried out or sanctioned by the people at large. Thousands of sober citizens stood upon the shore and watched the party, disguised as Indians, who hurled the hated tea overboard; so eminent a man as Samuel Adams led the party, and to this day no American has felt otherwise than proud of the significant and patriotic deed.

Events now hurried rapidly one upon another. The British Parliament’s reply to the Boston Tea Party was the Boston Port Bill, which absolutely forbade any trade in or out of the port. Simultaneously the charter of Massachusetts was changed so as to give the Crown almost unlimited power and to abolish town meetings, while it was made legal to quarter troops in Boston itself, and General Gage, the commander-in-chief of the British troops in the colonies, was made Governor of Massachusetts. This attack upon one of the colonies was regarded as a challenge to all. The system of correspondence committees started locally in Massachusetts and extended, at Virginia’s suggestion, between the colonies, for counsel and mutual support, was made the means of calling together at Philadelphia the first Continental Congress (September 5th, 1774). In this all the colonies but Georgia were represented, and among the delegates were George Washington and Patrick Henry, of Virginia; John and Samuel Adams, of Massachusetts; John Jay, of New York, and many others famous in our historical annals. This first really National Congress was moderate but firm in its action. It drew up a declaration of rights, which was a splendid recital of the wrongs complained of, prepared an address to the King, and adopted what was called the American Association, an agreement to prevent all importation from and exportation to Great Britain until justice was done; it adjourned with the expressed resolve to meet again, if necessary, the following year.

England now considered the colonies as in open rebellion, and indeed they were, at least in arms; Massachusetts alone had twenty thousand “minute men” ready to respond to the first call. And that call soon came. General Gage sent troops to the number of eight hundred to Concord, to destroy military stores there accumulated and to arrest Samuel Adams and John Hancock, to be sent for trial as traitors to England. The events of that expedition are familiar to us all. Boston was at that time a city of 17,000 inhabitants, guarded by 3000 British regulars. The inhabitants had patiently waited for the troops to strike the first blow, until the latter attributed their inaction to cowardice. But this expedition to arrest the American leaders would bring matters to the long-waited-for crisis. On that night (April 18) Paul Revere, in company with Davies and Prescott, started with a message from Dr. Joseph Warren, one of the leading spirits in Boston. The message was flashed by a lantern across the Charles river; it was to tell the farmers and townsfolk that the hour for resistance was come. A handful of colonists collected on the Lexington Green were fired upon by the British, and eight or ten were killed; the troops pressed on to Concord and seized the stores; but their retreat to Lexington was one long fight with the “embattled farmers” posted behind stone walls and trees and hidden in houses. When, reaching Lexington, the British were reinforced from Boston, they were so exhausted that a British writer says they laid down on the ground in the hollow square made by the fresh troops, ” with their tongues hanging out of their mouths like those of dogs after a chase.”The British had lost two hundred and seventy-three men; the Americans one hundred and three. Paul Revere’s midnight ride had fulfilled its mission. The “shot heard round the world” had been fired.

And the War Came.