About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Tecumseh’s War or Tecumseh’s Rebellion are terms used to describe a conflict in the Old Northwest between the United States and an American Indian confederacy led by the Shawnee leader Tecumseh. Although the war is often considered to have climaxed with William Henry Harrison’s victory at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811, Tecumseh’s War essentially continued into the War of 1812 and is frequently considered a part of that larger struggle. Tecumseh was killed by Americans at the Battle of the Thames in Canada in 1813 and his confederacy disintegrated. The tribes remaining in the newly expanded U.S. signed treaties and were forced to sell their lands and moved west by the 1830s. In long-term context, historians place Tecumseh’s War as the final conflict of the Sixty Years’ War resulting in the European conquest of the Great Lakes region.

The two principal adversaries in the conflict, Tecumseh and William Henry Harrison, had both been junior participants in the Battle of Fallen Timbers at the close of the Northwest Indian War in 1794. Tecumseh was not among the signers of the Treaty of Greenville that had ended the war and ceded much of present-day Ohio, long inhabited by the Shawnees and other Native Americans, to the United States. However, many Indian leaders in the region accepted the Greenville terms, and for the next ten years pan-tribal resistance to American hegemony faded.

After the Treaty of Greenville, most of the Ohio Shawnees settled at the Shawnee village of Wapakoneta on the Auglaize River, where they were led by Black Hoof, a senior chief who had signed the treaty. Little Turtle, a war chief of the Miamis, who had also participated in the earlier war and signed the Greenville Treaty, lived in his village on the Eel River. Both Black Hoof and Little Turtle urged cultural adaptation and accommodation with the United States.

The tribes of the region participated in several treaties including the Treaty of Grouseland and the Treaty of Vincennes that gave and recognized American possession of most of southern Indiana. The treaties resulted in an easing of tensions by allowing settlers into Indiana and appeasing the Indians with reimbursement for the lands the settlers were inhabiting via squatting.

In May 1805 Lenape Chief Buckongahelas, one of the most important native leaders in the region, died of either smallpox or influenza. The surrounding tribes believed his death was caused by a form of witchcraft and a witch-hunt ensued leading to the death of several suspected Lenape witches. The witch-hunts inspired a nativist religious revival led by Tecumseh’s brother Tenskwatawa (“The Prophet”) who emerged in 1805 as a leader among the witch hunters. He quickly posed a threat to the influence of the accommodationist chiefs, to whom Buckongahelas had belonged. As part of his religious teachings, Tenskwatawa urged Indians to reject European American ways, such as drinking liquor, European style clothing, and firearms. He also called for the tribes to refrain from ceding any more lands to the United States. Numerous Indians—who were inclined to cooperate with the United States—were accused of witchcraft, and some were executed by followers of Tenskwatawa. Black Hoof was accused in the witch-hunt but was not harmed. From his village at Greenville, Tenskwatawa compromised Black Hoof’s friendly relationship with the United States, leading to rising tensions with settlers in the region. Black Hoof and other tribal leaders began to put pressure on Tenskwatawa and his followers to leave the area to prevent the situation from escalating.[1]

By 1808, tensions with whites and the Wapakoneta Shawnees compelled Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh to retreat further northwest and establish the village of Prophetstown near the confluence of the Wabash and Tippecanoe Rivers, land claimed by the Miami. Little Turtle told the Shawnee that they were unwelcome there, but the warnings were ignored.[2] Tenskwatawa’s religious teachings became more widely known as they became more militant, and he attracted Native American followers from many different nations, including Shawnee, Canadian Iroquois, Chickamauga, Meskwaki, Miami, Mingo, Ojibwe, Ottawa, Kickapoo, Delaware (Lenape), Mascouten, Potawatomi, Sauk, and Wyandot.

In 1808 Tecumseh began to be seen as a leader by his community. In 1808 the British in Canada approached him to form an alliance, but he refused. It was not until 1810 that the Americans first took notice of him. Tecumseh eventually emerged as the leader of the confederation, but it was built upon a foundation established by the religious appeal of his younger brother.[2]

Willig (1997) states that Tippecanoe was the largest Native American community in the Great Lakes region and served as important cultural and religious center. It was an intertribal, religious stronghold along the Wabash River in Indiana for three thousand Native Americans, Tippecanoe, known as Prophetstown to whites. Led by Tenskwatawa initially, and later jointly with Tecumseh, thousands of Algonquin-speaking Indians gathered at Tippecanoe to gain spiritual strength.[3]

Meanwhile, in 1800, William Henry Harrison had become the governor of the newly formed Indiana Territory, with the capital at Vincennes. Harrison sought to secure title to Indian lands in order to allow for American expansion; in particular he hoped that the Indiana Territory would attract enough white settlers so as to qualify for statehood. Harrison negotiated numerous land cession treaties with American Indians.

In 1809 Harrison began to push for the need of another treaty to open more land for settlement. The Miami, Wea, and Kickapoo were “vehemently” opposed to selling any more land around the Wabash River.[4] In order to influence those groups to sell the land, Harrison decided, against the wishes of President James Madison, to first conclude a treaty with the tribes willing to sell and use them to help influence those who held out. In September 1809 he invited the Potawatomi, Lenape, Eel Rivers, and the Miami to a meeting in Fort Wayne. In the negotiations Harrison promised large subsidies and payments to the tribes if they would cede the lands he was asking for.[5]

Only the Miami opposed the treaty; they presented their copy of the Treaty of Greenville and read the section that guaranteed their possession of the lands around the Wabash River. They then explained the history of the region and how they had invited other tribes to settle in their territory as friends. The Miami were concerned that the Wea leaders were not present, although they were the primary inhabitants of the land being sold. The Miami also wanted any new land sales to be paid for by the acre, and not by the tract. Harrison agreed to make the treaty’s acceptance contingent on approval by the Wea and other tribes in the territory being purchased, but he refused to purchase land by the acre. He countered that it was better for the tribes to sell the land in tracts so as to prevent the Americans from only purchasing their best lands by the acre and leaving them only poor land to live on.[5]

After two weeks of negotiating, the Potawatomi leaders convinced the Miami to accept the treaty as reciprocity to the Potawatomi who had earlier accepted treaties less advantageous to them at the request of the Miami. Finally the Treaty of Fort Wayne was signed on September 30, 1809, selling the United States over 3,000,000 acres (approximately 12,000 km²), chiefly along the Wabash River north of Vincennes.[5] During the winter months, Harrison was able to obtain the acceptance of the Wea by offering them a large subsidy. The Kickapoo were closely allied with the Shawnee at Prophetstown and Harrison feared they would be difficult to sway. He offered the Wea an increased subsidy if the Kickapoo would also accept the treaty, causing the Wea to pressure the Kickapoo leaders to accept. By the spring of 1810 Harrison had completed negotiations and the treaty was finalized.[6]

Tecumseh was outraged by the Treaty of Fort Wayne, and thereafter he emerged as a prominent political leader. Tecumseh revived an idea advocated in previous years by the Shawnee leader Blue Jacket and the Mohawk leader Joseph Brant, which stated that American Indian land was owned in common by all tribes, and thus no land could be sold without agreement by all. Tecumseh knew that such “broad consensus was impossible”, but that is why he supported the position.[7] Not yet ready to confront the United States directly, Tecumseh’s primary adversaries were initially the Native American leaders who had signed the treaty, and he threatened to kill them all.[7]

Tecumseh began to expand on his brother’s teachings that called for the tribes to return to their ancestral ways, and began to connect the teachings with idea of a pan-tribal alliance. Tecumseh began to travel widely, urging warriors to abandon the accommodationist chiefs and to join the resistance at Prophetstown.[7]

Harrison was impressed by Tecumseh and even referred to him in one letter as “one of those uncommon geniuses.”[7] Harrison thought that Tecumseh had the potential to create a strong empire if he went unchecked. Harrison suspected that he was behind attempts to start an uprising, and feared that if he was able to achieve a larger tribal federation, the British would take advantage of the situation to press their claims to the Northwest.[8]

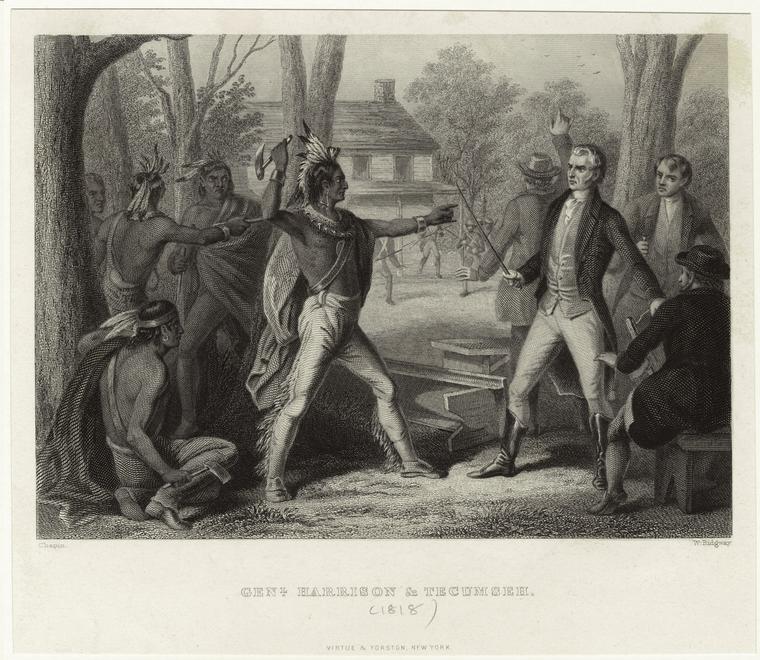

In August 1810 Tecumseh and 400 armed warriors traveled down the Wabash River to meet with Harrison in Vincennes. The warriors were all wearing war paint, and their sudden appearance at first frightened the soldiers at Vincennes. The leaders of the group were escorted to Grouseland where they met Harrison. Tecumseh insisted that the Fort Wayne treaty was illegitimate; he asked Harrison to nullify it and warned that Americans should not attempt to settle the lands sold in the treaty. Tecumseh acknowledged to Harrison that he had threatened to kill the chiefs who signed the treaty if they carried out its terms, and that his confederation was rapidly growing.[8] Harrison responded to Tecumseh that the Miami were the owners of the land and could sell it if they so choose. He also rejected Tecumseh’s claim that all the Indians formed one nation, and each nation could have separate relations with the United States. As proof Harrison told Tecumseh that the Great Spirit would have made all the tribes to speak one language if they were to be one nation.[9]

Tecumseh launched an “impassioned rebuttal”, but Harrison was unable to understand his language. A Shawnee who was friendly to Harrison cocked his pistol from the side lines to alert Harrison that Tecumseh’s speech was leading to trouble. Finally an army lieutenant who could speak Tecumseh’s language warned Harrison that he was encouraging the warriors with him to kill Harrison. Many of the warriors began to pull their weapons and Harrison pulled his sword. The entire town’s population was only 1,000 and Tecumseh’s men could have easily massacred the town, but once the few officers pulled their guns to defend Harrison the warriors backed down.[9] Chief Winnemac, who was friendly to Harrison, countered Tecumseh’s arguments to the warriors and instructed them that because they had come in peace, they should return in peace and fight another day. Before leaving, Tecumseh informed Harrison that unless the treaty was nullified, he would seek an alliance with the British.[10]

During the next year tensions began to rise quickly. Four settlers were murdered on the Missouri River and in another incident a boatload of supplies was seized by natives from a group of traders. Harrison summoned Tecumseh to Vincennes to explain the actions of his allies.[11] In August 1811, Tecumseh met with Harrison at Vincennes, assuring him that the Shawnee brothers meant to remain at peace with the United States. Tecumseh then traveled to the south on a mission to recruit allies among the “Five Civilized Tribes.” Most of the southern nations rejected his appeals, but a faction among the Creeks, who came to be known as the Red Sticks, answered his call to arms, leading to the Creek War, which also became a part of the War of 1812[12] Tecumseh delivered many passionate speeches and convinced many to join his cause.

| “ | Where today are the Pequot? Where are the Narragansett, the Mochican, the Pocanet, and other powerful tribes of our people? They have vanished before the avarice and oppression of the white man, as snow before the summer sun … Sleep not longer, O Choctaws and Chickasaws … Will not the bones of our dead be plowed up, and their graves turned into plowed fields? | ” |

| —- Tecumseh, 1811, ‘The Portable North American Indian Reader’[13] | ||

As tensions rose, Harrison openly denounced Tenskwatawa as a fraud and a fool, enraging him. Tecumseh ordered his brother to take no action, but his brother continued to call for the death of Harrison. Tenskwatawa lifted the ban on firearms and was able to quickly procure them in large quantities from the British in Canada. Tecumseh made a strategic error by leaving him alone to travel to the south.[14] Tenskwatawa took his brother’s absence as an opportunity to raise tensions even higher by further stirring up his followers.[15]

Harrison had left the territory to travel to Kentucky while Tecumseh was still away leaving Secretary John Gibson. Gibson had lived among the Indians for several years and soon heard from his friends that Tecumseh had secured an alliance with the British and procured weapons. He called out the territorial militia to prepare for the defense of the region and sent riders to recall Harrison. Harrison soon returned accompanied by 250 army regulars and 100 Kentucky volunteers. He gathered the scattered Indiana militia units, totaling about 600 men, and the Indiana Rangers together north of Vincennes.[16]

While Tecumseh was still in the south, Governor Harrison marched his army north along the Wabash River from Vincennes with more than 1,000 men on an expedition to intimidate the Prophet and his followers. His stated goal was to force them to accept peace, but he acknowledged that he would launch a preemptive attack on the natives if they refused. His army stopped near present day Terre Haute to construct Fort Harrison to guard an important position on the Wabash River. While at Fort Harrison, Harrison received orders from Secretary of War William Eustis authorizing him to use force if necessary to disperse the Indians at Prophetstown.[17] On November 6, 1811, Harrison’s army arrived outside Prophetstown, and Tenskwatawa agreed to meet Harrison in a conference to be held the next day. Tenskwatawa, perhaps suspecting that Harrison intended to attack the village, decided to risk a preemptive strike, sending out about 500 of his warriors against the American encampment. Before the dawn of the next day, the Indians attacked, but Harrison’s men held their ground, and the Indians withdrew from the village after the battle. The victorious Americans burned Prophetstown the following day and returned to Vincennes.[17]

Harrison—and many subsequent historians—claimed that the Battle of Tippecanoe was a deathblow to Tecumseh’s confederacy. Harrison, thereafter nicknamed “Tippecanoe”, eventually became the President of the United States largely on the memory of this victory. The battle was a severe blow for Tenskwatawa, who lost prestige and the confidence of his brother. However, although it was a significant setback, Tecumseh began to secretly rebuild the alliance upon his return from the south. By December, most of the major American papers began to carry stories on the battle. Public outrage quickly grew and many Americans blamed the British for inciting the tribes to violence and supplying them with firearms. Andrew Jackson was among the forefront of men calling for war, claiming that Indians were “excited by secret British agents.”[18] Other western governors called for action, William Blount of Tennessee called on the government to “purge the camps of Indians of every Englishmen to be found…”[19] Acting on popular sentiment, Congress passed resolutions condemning the British for interfering in American domestic affairs. Tippecanoe fueled the worsening tension with Britain, culminating in a declaration of war only a few months later.[20]

As the Americans went to war with the British, Tecumseh found British allies in Canada. Canadians would subsequently remember Tecumseh as a defender of Canada, but his actions in the War of 1812—which would cost him his life—were a continuation of his efforts to secure Native American independence from outside dominance. Tecumseh continued the struggle until his death in the 1813 Battle of Thames, ending the native uprising.