About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

It is hard to say how many years ago the Dakota Indians of the Northern Mississippi River began to spill over the

Missouri in search of game, and became hostile toward the other tribes claiming the western country. Dakota was their traditional tribal name, but as they crossed this Northwestern Rubicon they became known by the name the Chippewas had given them years ago: “Sioux”. It was by that moniker they became known as the most numerous and powerful nation of Native Americans — warriors, women, and children — to be found in the Northern Hemisphere. They were proud warriors when they launched

out on their expedition of conquest west of the Missouri. The Yellowstone river belonged to the Crows; the grassy prairie of Nebraska was the home of the Pawnees; the Black Hills were stomping grounds of the Cheyennes and Arrapahoes; the western side of the Big Horn range and the broad valleys between them and the Rocky Mountains were controlled by the Snakes; while roving parties of Crees rode down along the north shore of the Missouri river itself.

With the Chippewas behind them, and with the white settlers and soldiers in front, the Sioux waged relentless war. They drove the Pawnees across the Platte all the way to Kansas; they pushed both the Cheyennes and Arrapahoes out of the Black Hills, and down to the head waters of the Kaw and the Arkansas rivers; they fought the Snakes back into the Wind River Valley, with demands never to cross the boundary of the Big Horn River; and they sent the Crows running up the Yellowstone valley.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861 the Sioux aided the rebels considerably by raiding Northern settlements in Minnesota, massacring hundreds of women and children, families which had encroached on Sioux lands. General Sully was sent to punish them for these attacks. He marched far into their territory, and would fight them wherever he could find them, but it did no real good. The attempts to keep the Sioux in check during the Civil War did consume precious military resources. When the Civil War ended, and settlers began to move west, further encroaching into Sioux territory, they found the Sioux more aggressive than ever. The army was called on to protect these pioneers, and to escort the surveyors and railroad workers. In the years between 1866 and 1876, the cavalry had no rest; they fought year round; and during those ten years of “peace” more army officers were killed in combat with the American Indians than the British army lost in the entire Crimean war. The Indians had always been brave and skilled warriors, but in 1874 and 1875 the Sioux succeeded in arming themselves with modern rifles, becoming a foe more dreaded than any European cavalry. This combination of modern arms, incredible bravery, and superb horsemanship created a formidable fighting force.

Treaties were made and broken with the Sioux. A road had been built through the heart of the Big Horn and Yellowstone. Wooden forts were built, and manned by small groups of cavalry and infantry. From Ft. Laramie on the Platte up to the Gallatin Valley only those little forts: Reno, Phil Kearny, and C. F. Smith, guarded the way. Naturally the Sioux were concerned about these settlements on their lands. One day vast hordes of Sioux gathered in the ravines around Fort Phil Kearny.

Red Cloud was the fearless Sioux leader. He sent a small raiding party to attack the wood cutters from the fort, who were working with only minimal military protection. Two companies of infantry and one of cavalry went out to the rescue. They were quickly surrounded and then massacred. After that the Sioux had undisputed dominion over their territory for ten years. The US government’s forts were burned and abandoned. The allies of the Sioux joined with them, and a powerful nation of nearly 60,000 people ruled the country from the Big Horn River to the Union Pacific Railway. The Sioux would not go south of the Union Pacific Railroad.

Taking Cheyennes and Arrapahoes, who they had intermarried with, the Sioux went back to the North Platte and the territory beyond. From there they routinely raided in all directions. Attempts were made by the Government to bribe them, but with no lasting success. The U.S. established Indian Agencies and reservations at convenient points. Here the old men, the sick, and the women and children made their homes. Here the young warriors, laughing at the White Man, filled up their bags with ammunition and supplies. They then went on the war path, attacking any white settlers they could find. They would return to the reservation when they needed more supplies.

Two large reservations were created southeast of the Black Hills in the White River Valley. Red Cloud, the hero of the attack at Phil Kearny, made his home here. Many of his chiefs also gathered here: some “good”, like Old-Man-Afraid-of-his-Horses and his worthy son, but most of them crafty and combative, like Red Dog, Little-Big-Man, and American Horse. Further downstream, some twenty miles away, were the headquarters of the Brules. Their chief, Old Spot, was loyal to the U.S., but he had no control over the actions of the young warriors. Other reservations there were along the Missouri, and the Interior Department wanted to gather all of the Sioux Nation into these reservations, in order to help keep them out of trouble, or so it was thought.

The Sioux tradition, however, called for deeds of bravery in battle in order to win distinction. The vacillating policy of the US government allowed the Sioux warriors to make raids against white settlers, and to then return to the sanctuary of the reservation.

The warrior had won his spurs according to Sioux tradition, and was therefore a “brave”.

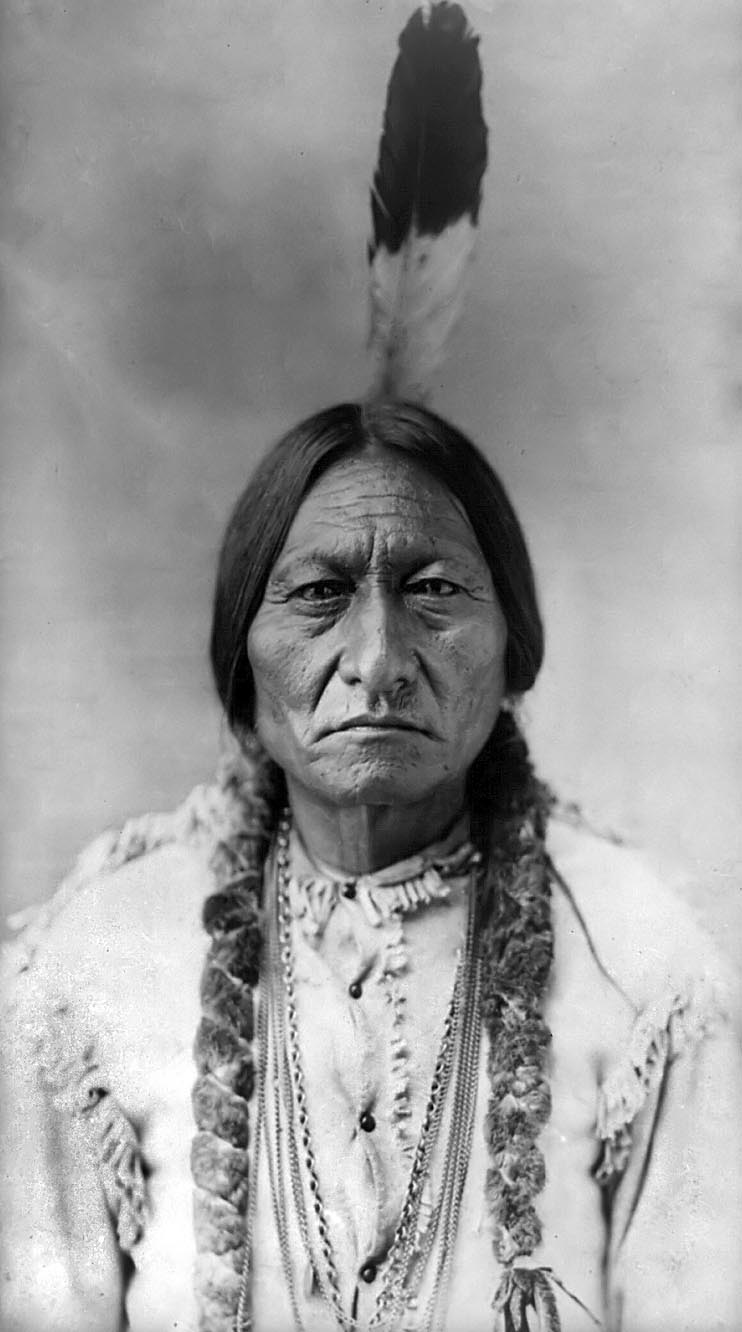

But there were those Great Chiefs who never came in and never made peace. One of those who refused, and whose stand was a rallying point for the disaffected of every tribe, was a shrewd “medicine chief”, the now celebrated Sitting Bull.

Sitting Bull and his followers were living happily and peaceably in the Valley of the Little Big Horn. Though the winters were cold and hard, they enjoyed life, as they hunted abundant game. But because of the US government’s new policy, all the renegades from other tribes flocked to this location.

The wild and angry Ogalalla, Brule, Blackfoot, and Sans Arc warriors all made a home here, and then set about to attack pioneers, settlers, surveyors and prospectors.

At this time, more white settlers were entering the Sioux lands in the Black Hills, most looking for gold. The Ogalallas and Brules killed the settlers, claiming them to be invaders.

Sitting Bull’s followers quickly grew. The Interior Department found it useless to delay any longer. The army received orders to either bring in Sitting Bull, or Snuff Him Out. Early in March of 1876 General George Crook was sent into Sioux country with a strong force of cavalry and infantry. Crook’s forces struck a big Indian Village on the snowy shores of the Powder River. It was thirty degrees below zero; the troops were poorly led by the officer entrusted with the duty, and the Sioux had recently developed impressive new fighting tactics under a new and daring leader, “Choonka-Witko” — known as Crazy Horse.

Crook’s advance retreated, being defeated by the renegades from the Red Cloud and Spotted Tail tribes. Early in May three expeditions moved into the territory, where by this time over 6,000 braves had joined Sitting Bull. From the south came Gen. Crook, with nearly 2,500 soldiers. From the east marched General Terry, with almost as many infantry and cavalry as had Crook, and a few light pieces of artillery. From the west General Gibbon led a group of frontier soldiers, scouting, and definitely finding the Indians on the Rosebud before forming his rendezvous with Terry near the mouth of the Tongue. If Sitting Bull had been aware of the situation, Gibbon’s small force could never have finished that movement.

Early in June Crook’s company was on the northeast slope of the Big Horn, and General Sheridan, planning the entire operation, saw with fear that large numbers of Indians were daily leaving the reservations south of the Black Hills and going around General Crook to join Sitting Bull. The Fifth Regiment of Cavalry was sent from Kansas to Cheyenne, and marched rapidly to the Black Hills to cut off these reinforcements. The great mass of the Indians lay between Crook at the head waters of Tongue River and Terry and Gibbon near its mouth, completely stopping all communications between the commanders. They harassed Crook’s outposts and supply trains, and by June Crook decided to engage them and see the strength of their force. On June 17th Crook skirmished with the Sioux on the bluffs of the Rosebud. He had several hundred Crow allies. The combat lasted much of the day; but long before it was half over Crook was on the defensive and was actually withdrawing his men. He had found a hornets’ nest, and knew it was too much for his small command. Pulling out as best he could, he fell back to the Tongue, sent for the entire Fifth Cavalry and all available infantry, and rested until they could reach him. Crook had not managed to even get within site of Sitting Bull’s Great Indian Village.

Meantime Terry and Gibbon sent their scouts up stream. Major Reno, with a strong battalion of the Seventh Cavalry, left camp to scout up the Wolf Mountains. Sitting Bull and his people decided it was time to move. Their camp stretched for six miles, and their thousands of horses had eaten all the grass. While they had been victorious, they decided it was time to move to the valley of the Little Big Horn. Marching up the Rosebud, Major Reno was confronted by the sight of an immense trail turning suddenly west and crossing the great divide over toward the west. Experienced Indian fighters in his command told him that thousands of Indians had crossed that way within the last few days. Reno wisely turned back, and reported what he had seen to Terry.

At the head of Terry’s cavalry was Brevet Major-General George Armstrong Custer, a daring, dashing, impetuous soldier,

who had won high honors as a division commander during the Civil War, and who had developed a reputation as an Indian Fighter when he led his gallant regiment against the Kiowas and the Cheyennes on the Southern plains. Custer had entered the Sioux country two times in recent campaigns. While Custer no doubt had experience, there were those who were superiors and subordinates who feared that Custer lacked the judgment needed to face a man like Sitting Bull on the Battlefield.

Custer had experienced conflict with both his commanders in the Dakota Department, and within his regiment. It is clear, however, that everyone honored his bravery and daring.

Some have speculated that the flamboyant Custer was considering a bid for the presidency, and that he sought one more bold and dramatic victory to secure his future.

When General Terry decided to send his cavalry to “scout the trail” reported by Reno, Custer was given command of the expedition.

Terry concluded that the Sioux had moved their camp across the Little Big Horn Valley, and he planned to send Custer to hold them from the east, while he and Gibbon’s troops pushed up the Yellowstone in boats. He would then march southward until he reached Sitting Bull’s flank.

Terry’s orders to Custer showed an unusual combination of anxiety and tolerance. He seems to have feared that Custer would be impetuous, but he resisted issuing an order that might wound the high spirited commander of the 7th Cavalry. Terry warned Custer to keep watch well out toward his left as he rode westward from the Rosebud, in order to prevent the Sioux from moving southeastward between the column and the Big Horn Mountains. He would not impede him with distinct orders as to what he must or must not do when he came in contact with the warriors, but he named the 26th of June as the day on which he and Gibbon would reach the valley of the Little Big Horn, and it was his hope and expectation that Custer would come up from the east about the same time, and between them they would be able to soundly whip the assembled Indians.

Custer let him down in an unexpected way. He got there a day ahead of time, and had ridden night and day to do it. Men and horses were exhausted when the Seventh Cavalry rode into sight of the Indian Village on the Little Big Horn that cloudless Sunday morning of the 25th. When Terry came up on the 26th, it was all over for Custer and his regiment.

Custer started on the trail with the 7th Cavalry, and nothing else. A battalion of the 2nd was with Gibbon’s column; but, luckily for the Second, Custer wanted none of them. Two field guns were with Terry, but Custer wanted only his own people. He rode 60 miles in 24 hours. He pushed ahead with focus and without hesitation. He created an impression that he wanted to have one dramatic battle with the Indians, in which he and the Seventh would be the only participants, and hence the heroes. The idea that he could be defeated apparently never crossed his mind. Custer sought glory, but in the end, found only infamy.

Crook had over 2,000 men only 30 miles to Custer’s left. If Custer had been scouting as instructed, he would have run into Crook’s outposts, and Crook could have reinforced him. Custer wanted nothing of the sort, and was savoring the chance to have all the Glory to himself. At daybreak his scouts had come across two or three warriors killed in the fight of the 17th, and they sent back word that the valley of the Little Horn was in sight ahead, and there were “signs” of the Indian Camp.

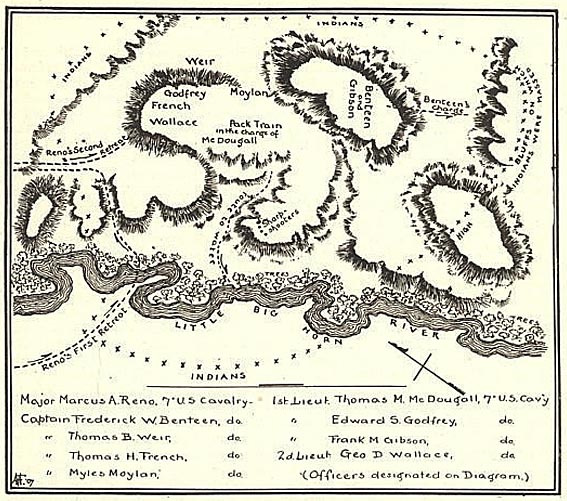

Custer then decided to divide his column. He kept 5 companies, commanded by close friends, with himself. He left Captain McDougal with some troops to guard the rear. He divided the remaining companies between Benteen and Reno. Benteen was sent two miles to the left, and Reno remained between Benteen and Custer. This formed three small columns of 7th cavalry, which moved quickly westward over the divide.

Custer’s troops went into battle with the pomp and parade of war that distinguished them around their camps. Bright guidons flew in the breeze; many of the officers and soldiers wore the casual uniform of the cavalry. George Custer, his brother Tom Custer, Cook and Keogh were all dressed alike in buckskin jackets and broad rimmed scouting hats, with long leather riding boots. Captain Yates seemed to prefer his undress uniform, as did most of the lieutenants in Custer’s column.

The brothers Custer and Captain Keogh rode Kentucky Sorrels. The trumpeters were at the heads of columns, but the band of the Seventh Cavalry had been left behind. Custer’s last charge was started in the absence of the Irish fighting tunes he loved so dearly.

Following Custer’s trail, you will come in sight of the Little Big Horn, snaking northward to its intersection with the broader stream. Looking southward you will see the cliffs and canyons of the mountains. To your North, the prairie reaches the horizon. To your West you see a broad valley on the other side of the stream. The fatal Greasy Grass is not seen below the steep bluffs that contain it. The stream comes into sight far to the left front, and comes toward you bordered by cottonwood and willow trees. It is lost behind the bluffs. For nearly six miles of its winding course, it can not be seen from where Custer got his first view of the village. Hundreds of “lodges” that lined its western bank could not be seen. Custer eagerly scanned the distant tepees that lay far to the North, and shouted “Custer’s luck! The biggest Indian Village on the Continent!” At this point he could not have seen even 1/3 of the village!

But what he could see was enough to fire the blood of a man like Custer. Huge clouds of dust, nervous horses, frantic horsemen making a run for it, and down along the village, lively turmoil an confusion. Tepees were being taken down quickly, and the women and children were fleeing the carnage that was about to come. We know now that the men he saw running westward were the young men going out to round up the horses. We know now that behind those sheltering bluffs were still thousands of fierce warriors eager and ready to meet George Custer. We know that the indications of the Indians panicking and retreating was due mainly to simply trying to get the families away from the fight that was to come. The warriors were by no means running from the fight, the brave warriors were making ready for battle!

Custer interpreted this confused scene as the Warring Indians being in full and speedy retreat. Custer determined that Reno should attack straight ahead, get to the valley and cross the stream. Reno could then attack the southern end of the camp. This would leave Custer and his companies to go into the long winding ravine that ran northwestward to the stream, and then attack aggressively from the east.

Custer sent a dispatch to Benteen and MacDougall, notifying them of his actions, and ordering them to hurry back with the pack trains, supplies, and extra ammunition. Custer placed himself at the head of his column, and charged down the slope, with his troops close behind. The last that Reno and his people saw of Custer was the tail of the column disappearing in a cloud of dust. Then only the cloud of dust could be seen hanging over the trail.

Moving forward, Reno came quickly to a gully that led down through the bluff to the stream. A quick run brought him to the ford; his soldiers plunged through, and began to climb the bank on the western shore. He expected from his orders to find an unobstructed valley, and five miles away the lodges of the Indian village. It was with surprise and grave concern that he suddenly rode into full view of a huge camp, whose southern border was less than two miles away. As far as he could see, the dust cloud rose above an excited Indian Camp. Herds of war horses were being run in from the west. Old men, women, children, and ponies were hurrying off toward the Big Horn. Reno realized that he was in front of the congregated warriors of the entire Sioux Nation in preparation for battle.

Most people think that Custer expected Reno to lead a dashing charge into the heart of the Indian Camp, just as Custer had done at Washita. Reno did not dash as Custer had expected. The sight of the Assembled Sioux Nation removed any desire Reno had ever had to dash into the camp. Reno attacked, but the attack was tentative and half-hearted. He dismounted his men, and advanced them across a mile or so of the prairie. He fired as he got within range of the village. He did not meet any resistance. The appearance of Reno’s command apparently came as a surprise to the Uncapapa and Blackfeet, who were on the South side of the camp. The scouts had given sign of Custer’s troops coming down the ravine. Those who had not run for cover were apparently running toward the Brule village, anticipating that Custer would strike there first.

Reno could have charged into the south end of the village before his approach could have been recognized. Instead, he approached slowly on foot. Reno had had no experience in fighting Indians. He simply concluded that his small column would not drive the mass of warriors from the valley. In much trepidation, he sounded a halt, rally, and mount. He then paused, as if he did not know what to do.

The Indians correctly sensed his hesitation, fear, and indecision. He lost the element of surprise, he lost his momentum, and he lost the confidence of his own troops. He emboldened his enemy; “The White Chief was scared”; and now was their opportunity. Warriors, men and boys, came tearing to the location. A few well-aimed shots knocked some men off of their horses. Reno quickly ordered a movement by the flank toward the bluffs across the stream to his right rear. He never thought to dismount a few cool guns to turn around and cover the enemy. He placed himself at the new head of column, and led the retreating movement. Out came the Indians, with shots and triumphant yells. The rear of the column began to overtake the head; Reno was walking while the rear was running. The Indians came dashing up on both flanks and the rear. At this point the poorly led and helpless troops had no choice. Military discipline and order were abandoned. In one mad rush they ran for the river, jumped in, splashed through, and climbed up the steep bluff on the eastern shore — an inexcusable panic, due mainly to the incompetent conduct of a cowardly commander.

In vain several of the best officers of the column (Donald McIntosh and Benny Hodgson) tried to rally and protect the rear of the column. The Indians were not in overpowering numbers at that point, and a bold stand could have saved the day. But with the Major on the run, the Lieutenants could do nothing, but die bravely, and in vain. Donald McIntosh was surrounded, knocked from his horse and butchered. Hodgson, shot off his horse, was rescued by a friend, who dove into the river with him, but close to the farther shore the Indians killed him, a bullet tore through his body, the gallant and brave man rolled dead into the muddy waters.

Once well up the bluffs, Reno’s command turned around and considered the situation. The Indians had stopped their pursuit, and even now were retreating from range. Reno fired his pistol at the distant warriors in useless defiance of the men who had stampeded him. He was now up some two hundred feet above them, and it was as safe as it was harmless. Two of his best men lay dead down on the banks of the river, and so did more than ten other of his soldiers. The Indians had swarmed all around his troops, and butchered them as they ran. Many more had been wounded, but things appeared safe for the moment. The Indians had mysteriously retreated from their front. Reno did not know what it meant, did not know what had happened to Custer, and did not know where the commands of Benteen and MacDougal were.

Over toward the villages, which they could now see stretching for five miles down the stream, all was total pandemonium and confusion; but northward the bluffs rose still higher to a point nearly opposite the middle of the villages — a point some two miles from them — and beyond that they could see nothing. But that is where Custer had gone, and suddenly, splitting through the moist morning air, came the sound of loud and rapid gunfire; complete volleys followed by continuous rattle and roar. The sounds of war grew more intense for the next ten minutes. Some thought they could hear the victory yells of their friends, and they were ready to yell in reply. Others thought they heard the sound of “charge” being blown on the trumpets. Many wanted to mount their horses, and join the fight, which sounded to be just over the bluffs.

But, almost as suddenly as it had started, the sound of gunfire faded away. The continuous peals of musketry settled into sporadic skirmishing fire. Reno’s men looked at each other in confusion. They could not figure out what had just happened.

Reno’s men were soon encouraged as they heard the reports of scouts that Benteen and MacDougal were approaching from the east. When they arrived the first thing they asked was, “Have you seen anything of Custer?”

Benteen and Weir scouted up to a mile or more to the north, had seen swarms of Indians in the valley below, but not a sign of Custer and his cavalry.

They concluded that there would be no help from Custer, and they did the only thing they could under these circumstances; they dug in and would try and hold out until Terry and Gibbon got there. Reno did not have the pack train, which gave him ample ammunition and supplies.

The question remained, what had happened to George Custer and his men? The question can only be answered by the Indians who were victorious that day, and one Indian who had been working for Custer. There was one Crow scout in Custer’s command who managed to escape the carnage of that day in a Sioux blanket. Between the lone survivor of Custer’s command, and the victorious Indian warriors, a fairly consistent story emerges. From all these sources it was not hard to trace Custer’s every move during that fateful battle.

Never comprehending the overwhelming odds against him, believing that the Indians were “on the run”, and thinking that between himself and Reno he could “double them up” in short order, Custer had sealed his fate. It was about five miles from where Custer first saw the northern end of the village and where he attacked the center of the village. During this 5 mile ride, Custer never saw the complete magnitude of the Indian Camp. As he attacked, and rounded the bluff, he found himself confronted with thousands skilled and well equipped warriors, all ready for the fight. He had hoped to attack the center of the village unmolested, and to meet Reno’s men there, coming from the other direction. Instead he faced an intense attack from the thickets and trees. He could not ignore the attack, and had to deal with the threat at hand. He had his men dismount, and begin engaging the fire coming from the thickets. This was a perilous move, as he was outnumbered ten to one at this point. Worse than that, hundreds of young braves had mounted their horses and dashed across the river below him, hundreds more were following and circling all about him. It is likely that this is the point that Custer realized that he was in trouble, and that he must cut his way out and escape the overwhelming enemy surrounding him.

His trumpeters sounded “Mount!”, and leaving many injured companions on the ground, the men ran for their mounts. With skill and daring, the Ogalallas and Brulés recognized the opportunity, and sprang to their horses, and gave chase. “Make for the heights!” must have been Custer’s order, for the first dash was eastward, and then more to the left as their progress was blocked.

Then, as Custer and the remainder of his regiments of 7th cavalry reached higher ground, they must have fully realized the gravity of their situation. For from this vantage point, all they would have been able to see would be throngs of skilled Sioux warrior on horseback, circling and laying down a furious fire. Custer and his command was fully hemmed in, cut off, and losing men quickly. Custer must have realized that at this point retreat was impossible. Some of the Indian victors later reported that at this point Custer ordered that the horses be turned loose, after losing about half of his men.

A skirmish line was then formed down the slope, and there the men fell at 25 feet intervals (It was here that their fellow soldiers found them two days later). At last, on a mound that stands at the northern end of a little ridge, Custer, Cook, Yates, Tom Custer, and some dozen other soldiers, (the only white men left alive at this point), gathered for the last stand. They undoubtedly fought fiercely, but lost their lives to the superior numbers, and superior leadership and strategy of the Indian Nation.

Keogh, Calhoun, Crittenden, had all been killed along the skirmish line. Smith, Porter, and Reily were found dead with the rest of their men. So were the surgeons, Lord and De Wolf; and, also, were Custer’s other brother, “Boston” Custer and the Herald correspondent.

Two men were not found among the dead. Lieutenants Harrington and Jack Sturgis. About 30 men had made a run for their lives down a little gully. The banks of the gully were teamed with Indians, who managed to shoot down the escaping soldiers as they ran. One officer was reported by the Sioux to have managed to break through the deadly circle of Indians, the only white man to do so that day. Five warriors gave chase. It is reported that as the pursuing band was worn down, and giving up the chase, the officer concluded that all was lost, and took his pistol, and shot himself in the head. This soldiers skeleton was pointed out to the officers of the Fifth Cavalry the following year by one of the pursuers. It had not been found before then. Was it Harrington or could it have been Sturgis? Some years later yet another skeleton was found even further from the battle scene. Remnants found at the scene indicated that it was a cavalry officer. If so, all the missing would be accounted for.

Of the twelve troops of the Seventh Cavalry, Custer led five that hot Sunday into eternity and infamy at the battle of the Little Big Horn, and of his part of the regiment only one living thing escaped the deadly skill of the Sioux warriors. Bleeding from many arrow wounds, weak, thirsty and tired, there came straggling into the lines some days after the fight Keogh’s splendid horse “Comanche”. Who can ever even imagine the scene as the soldiers thronged around the gallant steed?

Editorial Note: There are endless descriptions referring to this horse “Comanche” as the “only survivor of the Battle of Little Big Horn”. Please remember that there were thousands of brave and victorious survivors among the Indian Nations. They won the battle and they survived the battle. They were fighting for their lands, their family, and maybe most of all, for their way of life. In the end, their cause was lost, and their battle in vain, but we must remember, and honor their skill, bravery, and honor at this great event in our history.

As a tribute to his service and bravery, the war horse Comanche was never ridden again. He was stabled at Fort Riley, and would periodically be paraded by the US Army. He lived to the age of 29, and when he died his body was mounted and put on display at the University of Kansas, where it stands to this day.

With Custer’s men all dead, the triumphant Indians left their bodies to be plundered by their women. The warriors once more focused on Reno’s front. There were two nights of celebration and rejoicing in the Indian Camp, though not one instant was the watch on Reno eased. All day of the 26th they kept him penned down in his rifle pits. Early on the morning of the 27th, with great excitement, the lodges were suddenly taken down, and tribe after tribe, village after village, family after family, six thousand Indians passed before his eyes, moving towards the mountains.

Terry and Gibbon had arrived. Reno’s small remnant of the 7th cavalry had been saved. Together they reconnoitered the battlefield, and hastily buried their fallen comrades. They then hurried back to the Yellowstone while the Sioux were hiding in around the Big Horn. The Indians were shrewd enough to realize that Crook and Terry would be reinforced. They also realized that their victory would result in the US Army relentlessly pursuing them. As they heard that great numbers of troops were assembling near the Yellowstone and Platte, they took the only reasonable strategy that they could; the great Alliance of Indian Nations quietly dissolved. Sitting Bull, with many close associates, made for the Yellowstone, and was driven northward by General Miles. Others took refuge across the Little Missouri, where Crook pursued. With much hard pursuit, and even harder fighting, many bands and many famous chiefs were forced into submission that fall and winter. Among these, bravest, most skilled, most victorious of all, was the hero of the Powder River battle, the famed warrior Crazy Horse.

The fame of Crazy Horse, and his exploits had become the stuff of legends among the Indian camps along the Rosebud, even before he joined Sitting Bull. He was a key part of the battle with General Crook on June 17. No chief was as honored or trusted as Crazy Horse.

Up to the time of Little Big Horn, Sitting Bull had no real claims as a warrior, or as a war chief. Eleven days before the fight Sitting Bull had a “sun dance.” His own people report that while he was in a trance, he had a vision of his people being attacked by a large force of white men, and that the Sioux would enjoy a great victory over them. The battle of the 17th of June was a partial fulfillment of this vision.

Scouts in the Indian Camp had seen Reno’s column approaching, but it was decided that nothing would come of that. Sitting Bull believed that the army was waiting for reinforcements, and he had no expectations that an attack was imminent. Then on the morning of the 25th, two Cheyenne Scouts came running into camp, indicating that a large group of soldiers was approaching. Undoubtedly, this led to the commotion that Custer misread as a panic retreat.

Of course, such a report would mean that the women and children had to be hurried away, the great herds of horses brought in, and the warriors assembled to meet the coming adversary. Even as the great chiefs were running to the council lodge there came the report of gunfire from the south. This was Reno’s attack, which the Indians were not expecting. It is reported that the unexpected attack of Reno, and the report that “Long Hair” was dashing up the ravine was too much for Sitting Bull. He is reported to have gathered his family and made his escape to safety. Several miles from the battle, he realized that he was missing one of his children. As he began to return for the missing child, he was surprised to hear the battle waning, and everything becoming quiet. He returned to camp in about 30 minutes, where he found his child. He also found that the battle had been won in his absence.

Without him the Blackfeet and Uncapapas had pushed Reno back and penned him on the bluffs. Without him the Ogalallas, Brulés, and Cheyennes had repulsed Custer’s daring assault, then rushed forth and completed a circle of death that consumed Custer, and all the men with him. Again, it was Crazy Horse who was foremost in the fray, riding in and clubbing the bewildered soldiers with his immense club of war.

On this day, Sitting Bull’s vision was fully realized, but he was not there. Some loyal followers claimed that he had directed the battle from the lodge. The truth lay in the names given to Sitting Bull’s twins- “The one that was Taken”, and “The one that was Left”.

In the years after the conflict, many warriors would tell of their great exploits in the great battle. Rain in the Face would even brag that he had killed Custer with his own hand. In the midst of all the bravado and story telling one man emerged as the man most respected by his comrades on that glorious day. The man most respected by the Indians on that day, for his bravery and leadership, was Crazy Horse. Crazy Horse was killed not long after the battle as he tried to escape Crook’s guard.