About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

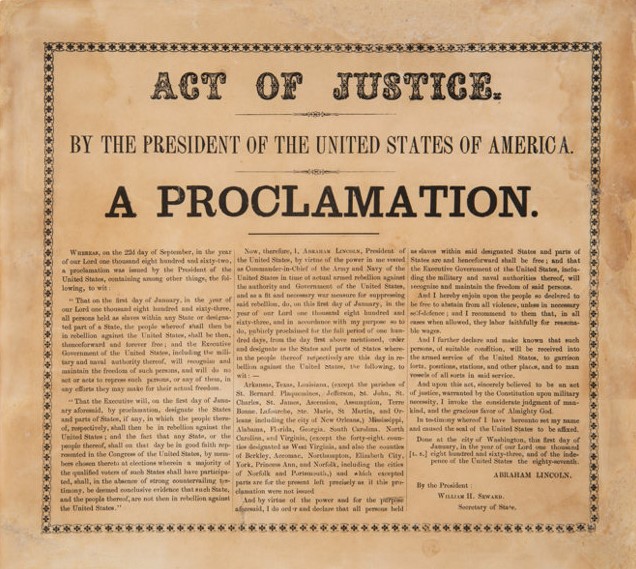

Author: Abraham Lincoln

Date:1862

Annotation:

On September 22, 1862, less than a week after the Battle of Antietam, President Lincoln met with his cabinet. As one cabinet member, Samuel P. Chase, recorded in his diary, the President told them that he had “thought a great deal about the relation of this war to Slavery”:

You all remember that, several weeks ago, I read to you an Order I had prepared on this subject, which, since then, my mind has been much occupied with this subject, and I have thought all along that the time for acting on it might very probably come. I think the time has come now. I wish it were a better time. I wish that we were in a better condition. The action of the army against the rebels has not been quite what I should have best liked. But they have been driven out of Maryland, and Pennsylvania is no longer in danger of invasion. When the rebel army was at Frederick, I determined, as soon as it should be driven out of Maryland, to issue a Proclamation of Emancipation such as I thought most likely to be useful. I said nothing to any one; but I made the promise to myself, and (hesitating a little)–to my Maker. The rebel army is now driven out, and I am going to fulfil that promise.

The preliminary emancipation proclamation that President Lincoln issued on September 22 stated that all slaves in designated parts of the South on January 1, 1863, would be freed. The President hoped that slave emancipation would undermine the Confederacy from within. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles reported that the President told him that freeing the slaves was “a military necessity, absolutely essential to the preservation of the Union….The slaves [are] undeniably an element of strength to those who [have] their service, and we must decide whether that element should be with us or against us.”

Fear of foreign intervention in the war also influenced Lincoln to consider emancipation. The Confederacy had assumed, mistakenly, that demand for cotton from textile mills would lead Britain to break the Union naval blockade. Nevertheless, there was a real danger of European involvement in the war. By redefining the war as a war against slavery, Lincoln hoped to generate support from European liberals.

Document:

“That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, and thenceforward, and forever, free; and the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

“That the Executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State, or the people thereof, shall on that day be in good faith represented in the Congress of the United States, by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified votes of such State shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State, and the people thereof, are not in rebellion against the United States.”

Now, therefore, I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested in me as commander-in-chief of the army and navy of the United States, in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do, on this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and in accordance with my purpose so to do, publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days from the day first above mentioned, order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof, respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States, the following to wit: Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James, Ascension, Assumption, Terre Bonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans), Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia (except the forty-eight country designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkeley, Accomae, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth.) and which excepted parts are for the present left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States and parts of States are and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known that such persons, of suitable conditions, will be received into the armed service of the United States, to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice warranted by the Constitution upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

Source: Gilder Lehrman Institute