About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Original Colonies. This page presents an overview of the 13 original American Colonies. Please note that you can click on the colony titles and be taken to in depth information on that colony.

Settlements in the new world were made in the following order: St. Augustine, Florida, was settled by Spaniards, under Pedro Menendez, 1565, and was the first European settlement. It was occupied by the Spaniards, except for a few years, until Florida passed from their control. While Florida was the area first settled by Europeans, it was not one of the original 13 colonies, as it was controlled by Spain.

The first English settlement in the new world was in Virginia, with the first permanent settlement made in 1607, directed by London merchants, who sent a colony of five ships to settle on Roanoke Island. Storms forced them into the Chesapeake Bay. They went up the Powhatan River, landed, and formed the settlement of Jamestown. The river was named the James River to honor their King. After various difficulties, the settlement prospered, and, in 1619, the first representative Assembly in Virginia was held at Jamestown. This assembly formed the foundation of what would become the State of Virginia.

The first English settlement in the new world was in Virginia, with the first permanent settlement made in 1607, directed by London merchants, who sent a colony of five ships to settle on Roanoke Island. Storms forced them into the Chesapeake Bay. They went up the Powhatan River, landed, and formed the settlement of Jamestown. The river was named the James River to honor their King. After various difficulties, the settlement prospered, and, in 1619, the first representative Assembly in Virginia was held at Jamestown. This assembly formed the foundation of what would become the State of Virginia.

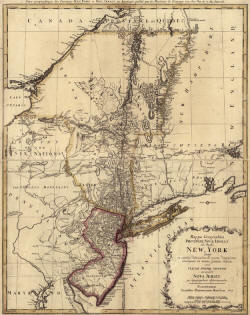

Manhattan Island, was discovered in 1609 by Henry Hudson, while working for the Dutch East India Company. Dutch traders soon settled there, and at Albany, about 150 miles up the Hudson River. The government in Holland gave exclusive rights to Amsterdam merchants to trade with the Native Americans on the Hudson, and the area was named New Netherland. The Dutch West India Company was created in 1621, with unrestricted oversight of New Netherland. They bought Manhattan Island from the Indians for about $24. The payment was made in trade for various cheap trinkets.

Manhattan Island, was discovered in 1609 by Henry Hudson, while working for the Dutch East India Company. Dutch traders soon settled there, and at Albany, about 150 miles up the Hudson River. The government in Holland gave exclusive rights to Amsterdam merchants to trade with the Native Americans on the Hudson, and the area was named New Netherland. The Dutch West India Company was created in 1621, with unrestricted oversight of New Netherland. They bought Manhattan Island from the Indians for about $24. The payment was made in trade for various cheap trinkets.

In 1623 Holland sent 30 families which started a settlement there. This settlement formed the basis for the State of New York (The name was changed from New Netherlald to New York when control passed to the British).

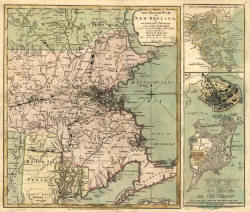

In 1620 a group of English Puritans who fled to Holland to escape persecution, crossed the Atlantic and landed on the shores of Massachusetts. They traveled with permission of the Plymouth Company. They built a settlement and named it New Plymouth. They created a government and called themselves “Pilgrims.” Others were soon to follow, and the foundations of the State of Massachusetts were laid. It is interesting to note that while the Pilgrims are often viewed as the first settlers, they were preceded by the St. Augustine and Jamestown settlements.

In 1620 a group of English Puritans who fled to Holland to escape persecution, crossed the Atlantic and landed on the shores of Massachusetts. They traveled with permission of the Plymouth Company. They built a settlement and named it New Plymouth. They created a government and called themselves “Pilgrims.” Others were soon to follow, and the foundations of the State of Massachusetts were laid. It is interesting to note that while the Pilgrims are often viewed as the first settlers, they were preceded by the St. Augustine and Jamestown settlements.

In 1622 the Plymouth Company granted to Mason and Gorges a tract of land bounded by the Merrimac and Kennebec rivers, the Atlantic ocean, and the St. Lawrence River. This area was soon settled by fishermen. Mason and Gorges dissolved their partnership in 1629. Emigrants from Connecticut and Massachusetts began to settle on the domain, but this was slowed by the French and Indian War. Afterwards, violent disputes with New York about grants ensued. On this tract of land between the Merrimac Kennebec, and St. Lawrence Rivers, the foundations for the commonwealth of NEW HAMPSHIRE were laid.

In 1622 the Plymouth Company granted to Mason and Gorges a tract of land bounded by the Merrimac and Kennebec rivers, the Atlantic ocean, and the St. Lawrence River. This area was soon settled by fishermen. Mason and Gorges dissolved their partnership in 1629. Emigrants from Connecticut and Massachusetts began to settle on the domain, but this was slowed by the French and Indian War. Afterwards, violent disputes with New York about grants ensued. On this tract of land between the Merrimac Kennebec, and St. Lawrence Rivers, the foundations for the commonwealth of NEW HAMPSHIRE were laid.

King James of England persecuted the Roman Catholics in his kingdom, and George Calvert, who was a zealous royalist, sought a refuge for his brethren in America. King James favored the idea, but died before anything was accomplished. His son Charles I. granted a domain between North and South Virginia to Calvert. Before the charter was completed Lord Baltimore died, but his son Cecil received it in 1632. The domain was called Maryland, and Cecil sent his brother Leonard, with colonists, to settle it. They arrived in the spring of 1634, and they laid the foundation for the commonwealth of Maryland at St. Mary.

King James of England persecuted the Roman Catholics in his kingdom, and George Calvert, who was a zealous royalist, sought a refuge for his brethren in America. King James favored the idea, but died before anything was accomplished. His son Charles I. granted a domain between North and South Virginia to Calvert. Before the charter was completed Lord Baltimore died, but his son Cecil received it in 1632. The domain was called Maryland, and Cecil sent his brother Leonard, with colonists, to settle it. They arrived in the spring of 1634, and they laid the foundation for the commonwealth of Maryland at St. Mary.

The Dutch explorer, ADRIAN BLOCK, sailing east from Manhattan, explored a river which the Indians called Quon-eh ti-cut. In the valley watered by that river a group of Puritans from Plymouth began a settlement in 1633. The first permanent settlement made in the valley of the Connecticut River was created by Puritans from Massachusetts, in 1636. This is the present site of Hartford. In 1638 another group from Massachusetts settled on the site of New Haven. The two settlements were politically united, and laid the foundations of the commonwealth of CONNECTICUT in 1639.

The Dutch explorer, ADRIAN BLOCK, sailing east from Manhattan, explored a river which the Indians called Quon-eh ti-cut. In the valley watered by that river a group of Puritans from Plymouth began a settlement in 1633. The first permanent settlement made in the valley of the Connecticut River was created by Puritans from Massachusetts, in 1636. This is the present site of Hartford. In 1638 another group from Massachusetts settled on the site of New Haven. The two settlements were politically united, and laid the foundations of the commonwealth of CONNECTICUT in 1639.

Meanwhile, there was interest in forming a new settlement between Connecticut and Plymouth. Roger Williams, a minister, was banished from Massachusetts in 1636. He went into the Indian country at the head of Narraganset Bay. He was joined by several people sympathetic to his plight. The group located themselves at the present site of Providence. Other people joined them, and they formed a purely democratic government. Others, persecuted at Boston, fled to the Island of Aquiday, or Aquitneek (now Rhode Island), in 1638, and formed a settlement there. The two settlements were consolidated under one government, called the Providence and Rhode Island Plantation, for which a charter was given in 1644. So the commonwealth of RHODE ISLAND was founded.

Meanwhile, there was interest in forming a new settlement between Connecticut and Plymouth. Roger Williams, a minister, was banished from Massachusetts in 1636. He went into the Indian country at the head of Narraganset Bay. He was joined by several people sympathetic to his plight. The group located themselves at the present site of Providence. Other people joined them, and they formed a purely democratic government. Others, persecuted at Boston, fled to the Island of Aquiday, or Aquitneek (now Rhode Island), in 1638, and formed a settlement there. The two settlements were consolidated under one government, called the Providence and Rhode Island Plantation, for which a charter was given in 1644. So the commonwealth of RHODE ISLAND was founded.

A small colony from Sweden made a town on the site of New Castle, Delaware, and called the area New Sweden. The Dutch claimed the region as a part of New Netherland, and the governor of New Netherland proceeded against the Swedes in the summer of 1655, and brought them under subjection. It is difficult to distinguish between the first settlements in Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, because of the early political situation.

A small colony from Sweden made a town on the site of New Castle, Delaware, and called the area New Sweden. The Dutch claimed the region as a part of New Netherland, and the governor of New Netherland proceeded against the Swedes in the summer of 1655, and brought them under subjection. It is difficult to distinguish between the first settlements in Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, because of the early political situation.

The (present) State of Delaware remained in possession of the Dutch, and afterwards of the English, until it was purchased by William Penn, in 1682, and annexed to PENNSYLVANIA. So it remained until the Revolution as “the Territories,” when it became the present State of DELAWARE.

New Jersey’s first permanent settlement was formed at Elizabethtown in 1644. A province lying between New Jersey and Maryland was granted to William Penn, in 1681, for a refuge for his persecuted brethren, the Quakers, and settlements were immediately begun there, in addition to some already made by the Swedes within the domain.

New Jersey’s first permanent settlement was formed at Elizabethtown in 1644. A province lying between New Jersey and Maryland was granted to William Penn, in 1681, for a refuge for his persecuted brethren, the Quakers, and settlements were immediately begun there, in addition to some already made by the Swedes within the domain.

Its territory was claimed to be a part of New Netherland by the Dutch. A few Dutch traders from New Amsterdam seem to have settled in about 1620, and in 1623 a company led by Captain Jacobus May built Fort Nassau, at the mouth of the Timmer Kill, near Gloucester. There four young married couples, with a few others, began a settlement the same year.

Unsuccessful attempts to colonize the area of the Carolinas had been made before the English landed at the James River. Some settlers went into North Carolina from Jamestown between the years 1640 and 1650, and in 1663 a settlement in the northern part of North Carolina had an organized government, and the country was named Carolina, in honor of King Charles II., of England. In 1668 the foundations of the commonwealth of NORTH CAROLINA were formed at Edenton. In 1670 some people from Barbadoes sailed into the harbor of Charleston and settled on the Ashley and Cooper rivers.

Unsuccessful attempts to colonize the area of the Carolinas had been made before the English landed at the James River. Some settlers went into North Carolina from Jamestown between the years 1640 and 1650, and in 1663 a settlement in the northern part of North Carolina had an organized government, and the country was named Carolina, in honor of King Charles II., of England. In 1668 the foundations of the commonwealth of NORTH CAROLINA were formed at Edenton. In 1670 some people from Barbadoes sailed into the harbor of Charleston and settled on the Ashley and Cooper rivers.

In 1729 Carolina became a royal province, and was divided permanently into two parts, called, respectively, North and SOUTH CAROLINA. The King of England bought the two Carolinas for $80,000. From that time until the French and Indian War the general history of the Carolinas presented nothing very remarkable, excepting their brave efforts for defending the colonies against the Indians and Spaniards. The South Carolinians warmly sympathized with the patriotic movements in the North preceding the Revolutionary War.

In 1729 Carolina became a royal province, and was divided permanently into two parts, called, respectively, North and SOUTH CAROLINA. The King of England bought the two Carolinas for $80,000. From that time until the French and Indian War the general history of the Carolinas presented nothing very remarkable, excepting their brave efforts for defending the colonies against the Indians and Spaniards. The South Carolinians warmly sympathized with the patriotic movements in the North preceding the Revolutionary War.

The benevolent General Oglethorpe, sympathizing with the condition of the debt prisoners in England, had the idea of creating a colony in America with the prisoners. The government approved, and, in 1732 he landed, with emigrants, near the present city of Savannah, and there planted the colony that would become the commonwealth of GEORGIA.

The benevolent General Oglethorpe, sympathizing with the condition of the debt prisoners in England, had the idea of creating a colony in America with the prisoners. The government approved, and, in 1732 he landed, with emigrants, near the present city of Savannah, and there planted the colony that would become the commonwealth of GEORGIA.

The first English colony settled in America was the one sent in 1585 by Sir Walter Raleigh. Raleigh dispatched Sir Richard Grenville, with seven ships and lots of people, to form a colony in Virginia. Ralph Lane was to serve as their governor. Grenville left 107 men at Roanoke Island to form a colony. The colony suffered from lack of supplies. The following year, Sir Francis Drake was sailing up the American Coast, and found them in distress. He generously provided them with supplies, a ship and small boats. He also left enough seamen to stay and further explore the country. The generosity was accepted, but a storm shattered his vessels, and discouraged the colonists. They decided to take passage for home with Drake. The colony sailed from Virginia June 18, 1586, and arrived at Portsmouth, England, July 28.

Madame de Guercheville, a pious lady in France, eager to convert the American Indians, convinced De Monts to surrender his patent. She then obtained a charter for “all the lands of New France.” In 1613 she sent out missionaries. They sailed from Honfleur March 12, and arrived in ACADIA. Her agent proceeded to Port Royal (now Annapolis), where he found only five persons, two of whom were Jesuit missionaries who had been sent earlier. They went to Mount Desert Island. Just as they had begun to find provisions, they were attacked by SAMUEL ARGALL, of Virginia. They made some resistance, but were overwhelmed and had to surrender. One of the Jesuits was killed, several were wounded, and the rest were made prisoners. Argall took fifteen of the Frenchmen, besides the Jesuits, to Virginia; the remainder sailed for France. This success motivated the governor of Virginia to send an expedition to destroy the power and influence of the French in Acadia, under the argument that they were encroaching upon the rights of the English. Argall sailed with three ships for the purpose. He arrived at St. Saviour, and broke up a cross the Jesuits had set up there. He sailed to St. Croix and destroyed the remains of De Mont’s settlement; and then he went to Port Royal and burned what was left of that town. The English government did not approve of his actions, nor did the French government resent it.

Though the revolution in England (1688) found supporters among the Low Churchmen and Nonconformists there, who composed the English Whig party, the high ideas which William entertained of royal authority made him naturally coalesce with the Tories and the High Church party. As to the government of the colonies, he continued the oppressive policies of his predecessors. The colonial assemblies had hastened to enact in behalf of the people the Bill of Rights of the Convention Parliament. To these William gave frequent and decided negatives. The colonists’ attempt to gain the writ of habeas corpus was also vetoed by the King. He also continued the prohibition of printing in the colonies. Even men of liberal tendencies, like Locke, Somers, and Chief-Justice Holt conceded prerogatives to the King in the colonies which they denied him at home. The most renowned jurists of the kingdom had not yet understood the true nature of the connective principle between the parent country and her colonies.

As early as 1696 a pamphlet circulated in England suggesting Parliament should tax the colonies. Two pamphlets appeared in reply, arguing against the right of Parliament to tax the colonies, because they had no representative in Parliament to give consent. From that day the subject of taxing the colonies was a question frequently discussed, but not attempted until seven decades later. After the ratification of the treaty of Paris in 1763, the British government resolved to quarter troops in America at the expense of the colonies. The money was to be generated by a tax on foreign sugar and molasses, and by stamps. It was determined to tax the American colonists in a way which Walpole feared to undertake. A debate arose in the House of Commons on the right of Parliament to tax the Americans without allowing them to be represented in that body. The question was decided by an almost unanimous vote in favor of taxation. ” Until then no act, avowedly for the purpose of revenue, and with the ordinary title and recital taken together, is found on the statute-book of the realm,” said Burke. ” All before stood on commercial regulations and restraints.” Then the House proceeded to consider the STAMP ACT.

In 1697 the right of appeal from the colonial courts to the King in council was sustained by the highest legal authority. By this and the establishment of courts of admiralty, England acquired a judicial control over the colonies, and with it a power of bringing her supreme authority to bear on both the colonies, and the colonists.

At the beginning of the French and Indian War (1754), the period when the American people “set up for themselves” in political and social life, there was no exact count of the inhabitants; but from a careful examination of official records, Mr. Bancroft estimated the number as follows:

Colonies |

White |

Colored |

| Massachusetts | 207,000 | 3000 |

| New Hampshire | 50,000 | 3000 |

| Connecticut | 133,000 | 3,500 |

| Rhode Island | 35,000 | 4,500 |

| New York | 85,000 | 11,000 |

| New Jersey | 73,000 | 5,000 |

| Pennsylvania and Delaware | 195,000 | 11,000 |

| Maryland | 104,000 | 44,000 |

| Virginia | 168,000 | 116,000 |

| North Carolina | 70,000 | 20,000 |

| South Carolina | 40,000 | 40,000 |

| Georgia | 5,000 | 2,000 |

| Total | 1,165,000 | 260,000 |

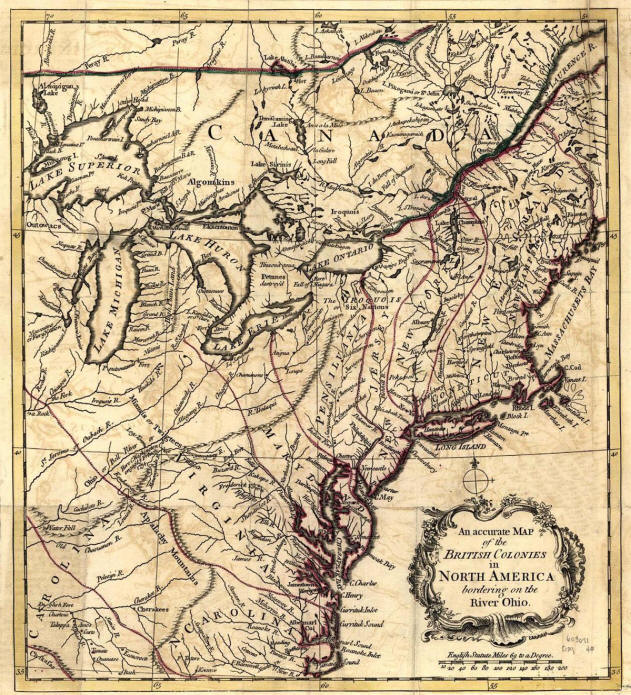

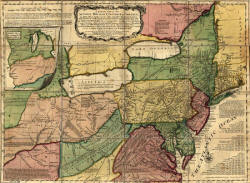

At this period the extent of the territorial claims of England and France was well defined on maps published by Evans and Mitchell in 1754. The British North American colonies stretched coastwise along the Atlantic about 1,000 miles, but inland their extent was very limited. New France extended over a much wider space, from Cape Breton to the mouth of the Mississippi River. The English colonies at that time had a population of 1,485,634, of whom 292,738 were negroes. The French were about 100,000 in number, but they had strong alliances with the Indians. The Indians populated the region on the interior edge of the British colonies. The Indians were frustrated with the constant encroachments and poor treatment by the English, were always ready for war.

The French and Indian War, and the conflicts with England revealed to the colonists their innate strength. During these confrontations, disease and weapons had claimed 30,000 of the colonists. They had also spent more than $16,000,000, of which $5,000,000 had been reimbursed by the British Parliament.

The colonists began to demand a position of political equality with their fellow subjects in England, and were ready to maintain their rights through armed struggle.

In Pitt’s cabinet, as chancellor of the exchequer, was Charles Townshend. He had voted for the Stamp Act, and voted for its repeal. In January, 1767, he proposed taxation schemes which met with strong opposition in America. He introduced a bill imposing a tax on tea, glass, paints, lead, paper, and other articles of British manufacture brought into the colonies. It was passed June 29. By another act, reorganizing the colonial custom-house system, a board of revenue commissioners for America was established, to have its seat at Boston. Connected with these bills were provisions very obnoxious to the Americans, all related to raising tax revenue in America.

There was a provision in the first bill for the maintenance of a standing army in the colonies and allowing the crown to establish a general civil list; setting the salaries of governors, judges, and other officers, with the salaries to be paid by the crown, making these officers independent making of the people of the colonies.

In striking a balance of losses and gains in the matter of parliamentary taxation in America, it was found in 1772 that the expenses on account of the Stamp Act exceeded $60,000, while it had raised only $7,500. The tea tax had been even worse. The whole tax revenue from the colonies for the previous year for duties on teas and wines amounted to no more than about $400, while ships and soldiers for the support of the tax had cost about $500,000; and the East India Company had lost the sale of goods to the amount of $2,500,000 annually for several years.

After the proclamation of King George III., in 1775, Joseph Hawley, one of the stanch patriots of New England, wrote to Samuel Adams : ” The eyes of all the continent are on your body to see whether you act with firmness and intrepidity-with the spirit and dispatch which our situation calls for. It is time for your body to fix on periodical annual elections-nay, to form into a parliament of two houses.” This was the first proposition for the establishment of an independent national government for the colonies.

On April 6, 1776, the Continental Congress, by resolution, threw open their ports to the commerce of the world ” not subject to the King of Great Britain.” This was a declaration of absolute free trade, and the act was a virtual declaration of independence.