About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Frederick Douglass was a “from here.” Where I was raised, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, a “from here” is the opposite of a “come here,” and much is made of whether you were born on this side of the Chesapeake Bay or arrived later in life. In weighty matters, the question of just how many generations of your family have called this place home can become relevant, too.

One such matter is the Confederate monument at the Talbot County Courthouse, in Easton, a town of about seventeen thousand people. The monument, which is the last in Maryland on public property outside of cemeteries and battlefields, has two parts: a granite base, which was erected in 1914 and bears the names of ninety-six Confederate soldiers with some connection to the county—most carved in stone, others on two brass plaques—and a six-foot-tall statue, added two years later, of a young man with “C.S.A.” carved into his belt buckle and a Confederate flag in his arms. The front of the base is inscribed “To the Talbot Boys / 1861–1865 / C.S.A.”

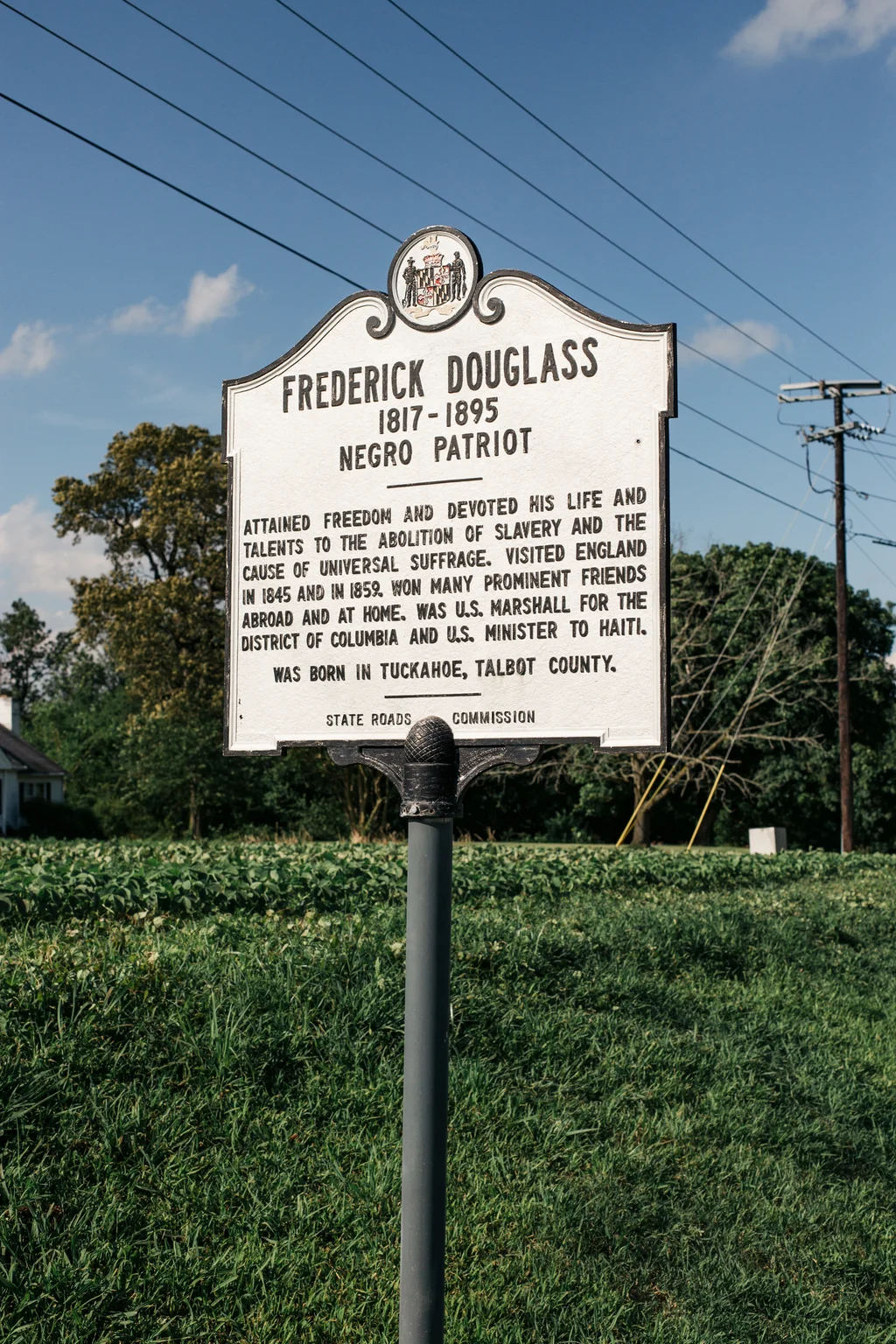

For most of the past decade, that monument has shared the courthouse lawn with another: of Douglass, who was born into slavery some twelve miles from where his statue stands. Probably no one would be more surprised by this arrangement than Douglass himself, whose home state never seceded from the United States and whose home county voted against secession, sending more than three hundred soldiers to the Union Army. And yet there is no monument for the Union dead at the courthouse, or anywhere else in Talbot County.

The absence of a Union monument and the prominence of a Confederate one are part of why many a “from here,” like me, grew up believing that Talbot County was a Confederate stronghold. I love where I am from, so much so that I moved back to the Eastern Shore as an adult and, for years now, I have been one of many residents advocating for the removal of the “Talbot Boys” from the courthouse lawn. Earlier this summer, I thought I might be able to tell the story of how the Confederate monument finally came down. Instead, I’m left to confront why it remains.

Talbot County’s monument was installed fifty years after the Civil War, in an era when the gains of Reconstruction were already being reversed, Jim Crow was under way, and revanchist public commemorations of the Confederacy were spreading across the country. Thousands of squares and streets were dedicated to Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis and Stonewall Jackson, and historical markers to Confederate sites and causes went up anywhere that the United Daughters of the Confederacy could inspire local action. So common were these memorials that there were companies devoted to their production. Though defenders of the “Talbot Boys” insist that the statue is a one-of-a-kind effort to honor the local dead, in reality it once had an identical twin, known as “The South’s Defenders,” on the lawn of the Calcasieu Parish courthouse, in Lake Charles, Louisiana. Both statues came from the W. H. Mullins Company, in Salem, Ohio, which had so many Civil War wares on offer that it advertised them in a catalogue: “The Blue and the Gray: Statues in Stamped Copper and Bronze.”

Advocates for the “Talbot Boys” also like to say that the monument has nothing to do with slavery, and that the political beliefs of those who are honored on it and those who erected it are unknowable or distinct from the motivations of Confederate champions elsewhere. In fact, many of those involved left extensive archives of their lives, detailing their thoughts about the Civil War and everything else. The effort to erect Easton’s statue was started in 1912, by a lawyer named Joseph Seth. He was not a Confederate veteran, but he was a sympathizer. He was also active in local politics, eventually becoming mayor, and not long before his election he decided the time had come to honor the “Talbot Johnnies.” The statue was dedicated on June 5, 1916. Ten years later, Seth published a memoir with his second wife, Mary, which recorded his views on, among other things, race relations on the Eastern Shore. “Slaves were held here from the early days of the Colony until the Emancipation Act, but they lived under a paternal, kindly rule,” he claimed.

That does not comport with the narratives of slavery from the enslaved themselves, and certainly not with the most notable account from someone forced to live and work in bondage in Talbot County. In his autobiography, Frederick Douglass wrote of his master:

At least fourteen of the men whose names appear on the Confederate monument in Easton owned slaves or belonged to slave-owning families, including the man whose name comes first: Admiral Franklin Buchanan, who married into the Lloyd family, which enslaved more than seven hundred people, Douglass among them, at their Wye House plantation. In the passage above, the man whom Douglass is describing worked for the Lloyds. The year before the Civil War began, nearly four thousand people were enslaved in Talbot County. Easton’s port had become a hub for the domestic slave trade, and the town’s slave market was located on the very grounds where the Confederate statue now stands.

The surnames on that statue also appear on local streets, towns, landmarks, and landings: a geography of place and power. Take “Tilghman,” the name of a nearby island, but also of Oswald Tilghman, who survived the war and helped Seth raise money for the monument. Around the same time that it was erected, Tilghman published a “History of Talbot County,” in which he described the death of another one of the statue’s honorees, his relative Lloyd Tilghman, at the Battle of Champion Hill, in Mississippi: “He was laid under the shade of a peach tree where his life’s blood ebbed slowly away, and another hero was added to that long list of martyrs who died for the cause, ‘the lost cause,’ though it be, still dear and will ever remain dear to the hearts of all true Southerners to the end of time.”

The movement to relocate Easton’s Confederate monument began with a movement to erect a different one. In 2002, the Talbot Historical Society began exploring the life of Frederick Douglass; to better acknowledge his connection to the region, they proposed a statue in his honor on the courthouse green. But, when they brought the idea before the county council, they were told by its members that there was an “unwritten rule” that only veterans could be honored at the courthouse. Dozens of local veterans voiced opposition to the Douglass statue on the basis of that dubious rule, and for a few months the Star Democrat, Easton’s local newspaper, was filled with letters to the editor debating the appropriateness of paying tribute to one of the nation’s most famous abolitionists on the courthouse lawn. When the council finally approved the Douglass statue, in 2004, it did so by a single vote. That approval came with some conditions, including this one: “The policy adopted by the county is that any new statue would not exceed the proportions or dimensions of other statues,” Philip Carey Foster said, in rejecting the first design for the Douglass memorial, on the ground that it was taller than the “Talbot Boys.” “And anyone who didn’t die in a war would not be acknowledged as greater than those who did.”

It took another seven years to get the Douglass statue installed. When it finally was, many thought that settled the matter of statues on the courthouse lawn. Instead, the discussion it had provoked about who deserved pride of place in the county led to questions about who did not. That conversation came to a head in 2015, after a white supremacist murdered nine people at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, in Charleston, South Carolina. A few weeks later, Richard Potter, the president of the local chapter of the N.A.A.C.P., asked the county council to formally consider removing the “Talbot Boys” statue.

Potter was born and raised in Easton—a “from here,” although defenders of the monument often insist on portraying the N.A.A.C.P. as a group of outside agitators. One letter to the Star Democrat claimed that “these people,” including Potter’s organization, were “attempting to force their opinions on the people of this county.” But Potter can remember looking up at the Confederate monument as a young child and wondering what a boy had to do to become a statue; only later did he realize what this particular human figure represented. Then he began to wonder why he and everyone else had to pass by a Confederate statue in order to get a marriage license or serve on a jury or go to court; his members asked him how such a symbol could stand outside the very courts and offices ostensibly promising fairness and justice. Eventually, Potter, on behalf of the N.A.A.C.P., presented a three-part proposal to the council: remove the monument, research the Civil War, and produce an accurate memorial.

In the fall of 2015, after a series of meetings with activists, clergy, and the general public, the council held a vote behind closed doors—the first of many irregularities in how it has handled the issue—and announced its decision not to relocate the monument. When that vote was found to have violated Maryland’s open-meeting laws, the council was forced to vote again, publicly, in the summer of 2016. By then, private letters and public comments had turned into protests for removal. Nonetheless, the council voted unanimously to keep the monument on the courthouse lawn.

Every so often, in the years that followed, a petition for removal would circulate, or something would occasion a new round of letters and protest: the removal of Confederate monuments in New Orleans, the murder of a counter-protester by a white supremacist in Charlottesville, the two-hundredth anniversary of Douglass’s birth, the removal of all other Confederate statues outside battlefields and cemeteries in the state of Maryland. The most recent such event was the murder of George Floyd, which sparked one of the largest public protests in the county’s recent history: around a thousand people joined a Black Lives Matter gathering in Talbot County in June, which ended with some attendees leaving their signs and placards at the monument, including a sign at the feet of the “Talbot Boys” that read “still???”

By then, at least two people in a position to answer that question had concluded that it was time for the statue to go. One of them was Pete Lesher: the only Democrat on the county council, a curator at the nearby Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, and a descendent of some of those named on the monument. The other was the president of the county council, a Black Republican named Corey Pack, who five years earlier had voted to protect the monument. Now Pack felt that it was no longer appropriate for public property, and, not long after the Black Lives Matter protest, he introduced a resolution for its removal.

Pack was born in Baltimore, but he moved his family to Easton in 2002, when he became a field supervisor for the Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services. He was appointed to the council in 2007 and has been reëlected three times. In the years since Pack voted to keep the Confederate statue, he has talked with more and more African-Americans about their experiences of previous decades on the Eastern Shore.

The segregation that existed here before the Civil War remained entrenched in the decades after it. In 1919, not long after the Confederate monument was installed, a mob of some two thousand people surrounded the courthouse in an attempt to lynch a Black man named Isaiah Fountain, who was being tried for the rape of a teen-age girl. In 1924, another would-be lynch mob was thwarted only when a local baseball hero, John Franklin (Home Run) Baker, prevented its members from lynching a Black man accused of assaulting Baker’s sister-in-law. In 1957, the year after schools in Talbot County began to integrate, eight hundred whites came together to form the Talbot County Citizens Association, which picketed elementary schools with signs that read “Let’s Keep Our Schools White.” One of the first Black families to send their children to a white school—two little boys, ages six and seven—found a bomb on their front lawn in Easton, its seven-foot fuse burned to within a few inches of detonating. In 1986, four locals were arrested for burning a cross on the lawn of the only Black family on Tilghman Island. After they received their sentences, which ranged from community service to six months in jail, the Ku Klux Klan held a rally at the courthouse, to protest their treatment. By then, the Black family had already moved away from the Eastern Shore.

In 1991, three Black employees of the Talbot County Roads Department, with the assistance of the A.C.L.U., filed a lawsuit alleging “an unbroken pattern of racial discrimination, segregation, and harassment.” They described supervisors segregating road crews, harassing Black workers with racial epithets, and denying minority employees opportunities for overtime work, promotions, and training. A U.S. District Court ordered the county to pay a settlement and court fees—and to develop proposals to address racial discrimination in local government. In 2000, a Black corrections officer filed charges of discrimination against the county’s detention center. A similar suit was later filed against the county’s schools.

Growing up, I saw Confederate flags on bumper stickers and T-shirts and baseball caps all around the county, but I didn’t learn any of this history. In school, we were taught about the Talbot Boys but not about the Hill, a free Black neighborhood in downtown Easton thought by some historians to be one of the oldest such communities in the country. We were taught about the naval career of Admiral Buchanan but not about Unionville, a community outside Easton which was settled by former slaves and free people of color, including eighteen Black veterans of the Union Army. When we were taught the history of the civil-rights movement, the boycotts and marches in faraway Montgomery were portrayed as necessary and heroic, but similar actions in nearby Cambridge were depicted as dangerous and thuggish. We read about the tragedy of the four little girls at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, in Birmingham, but not the attempted murder of two boys who helped integrate the very schools we attended.

These omissions added up to a distorted vision of life on the Eastern Shore, and they have allowed some residents to feel that this place is different from everywhere else in America. Some have claimed that our local Civil War history is uniquely complex because Maryland was a border state with divided loyalties. But that claim ignores the complexities of the Civil War everywhere, from the unionist volunteers of Nickajack, in the Deep South, to the Copperheads, in the North. More troublingly, some have suggested that, despite our history of enslavement and Confederate sympathies, we have not merely developed but have somehow always possessed a kind of local immunity to the racism that afflicts every other community in this country.

The idea that racism isn’t really a problem here was articulated most recently and most shockingly by one of Pack’s colleagues on the county council, Laura Price. Born and raised in Talbot County, Price runs a printing and shipping business in Easton.

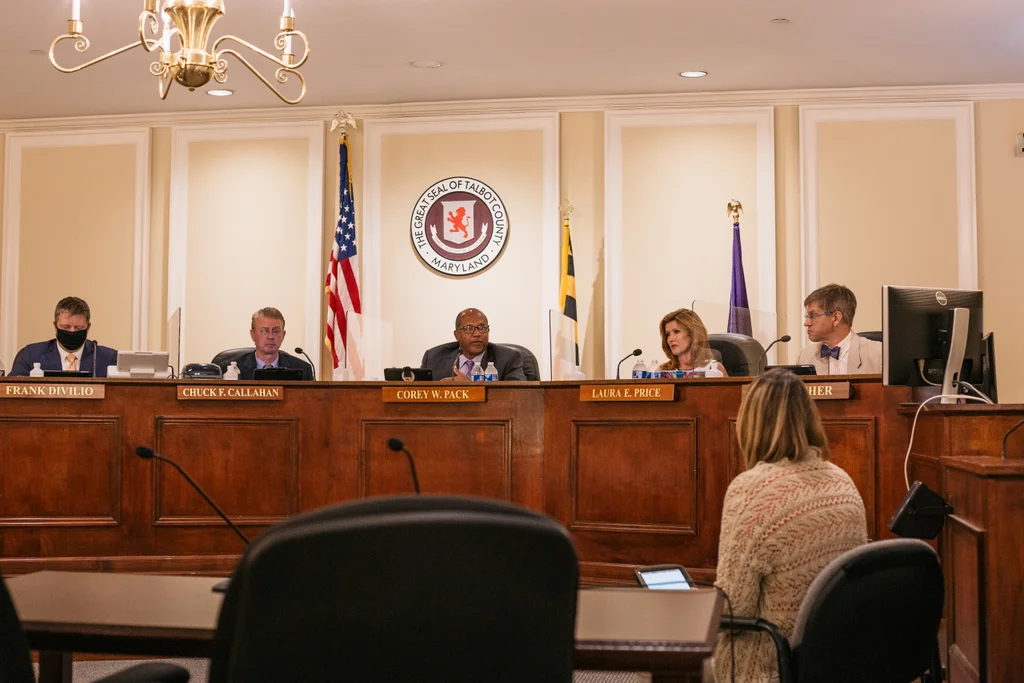

Pack put forward his resolution to remove the statue at a council meeting earlier this summer. The members were gathered, on a Tuesday evening, in a long, stately meeting room in the south wing of the courthouse where the “Talbot Boys” monument stands. Price and Pack were seated beside each other on the dais, separated by a philosophical gulf and a plexiglass coronavirus barrier. Hanging above them was the county seal, its motto an accidental commentary on the scene: “Tempus Praeteritum et Futurum,” “Times Past and Future.”

Pack proposed two other measures in addition to removing the statue: adding a diversity statement to the county’s employee handbook and requiring the county manager to produce an annual report on diversity trainings in county government. While the other three council members listened as he explained his reasoning, Price interrupted him repeatedly. She suggested that the council had more important business, pleaded to delay any vote, queried the county manager about his ability to comply with such regulations, and, finally, began voicing her opposition more directly.

“We haven’t had any complaints, no lawsuits,” Price said. “And I don’t necessarily think that we have to create a problem that, thank God, does not exist in Talbot County government.” She accused her colleagues of “reacting emotionally,” adding, “There’s a lot of things besides just racial issues that people need to think about when they’re treating each other, and to single that one thing out—”

“What one thing are you talking about?” Pack asked, before she could finish. “Single what one thing out?”

Price, looking nonplussed, answered, “Diversity training,” at which point Pack explained that diversity encompasses more than race.

During the public-comment period that followed, Richard Potter, of the N.A.A.C.P., who was watching a live stream of the meeting at home, called in to speak. “I’m appalled at listening to the discussion from your council county councilwoman Laura Price, as it relates to her resistance to creating a diversity statement, training, and diversity reports,” he began, during what should have been his allotted three minutes of speaking time. “Councilwoman Price’s constant reiteration—”

“Excuse me?” Price interrupted. “This has got to stop.” She began packing her purse, flustered and furious, and rose from her seat. “If you don’t stop him, I’m leaving,” she said. Potter was muted, the call was terminated, and the public-comment period was abruptly ended.

It was hard to miss the temerity of a county-council member disputing the existence of racism in county governance shortly before silencing the local president of the N.A.A.C.P. And it was not the first time that Price had tried to quash public input: at an earlier meeting, she challenged a different caller, who was also advocating for the statue’s removal, by saying that the public-comment period should be reserved “for Talbot County citizens,” a requirement that does not exist. Later that summer, the ostensible public hearing on the statue resolution was closed to the public entirely, even though previous council meetings during the pandemic had merely limited entry and enforced social distancing and mask-wearing. By then, Price had stopped attending the meetings in person, although the other council members continued to show up.

Closing the meetings did not deter people from sharing their opinions by phone, e-mail, letter, and protest. I wrote my own e-mail, as did hundreds of others—more than have contacted the county council on any other recent matter. At the official hearing, twenty-eight callers voiced their support for the statue’s removal; only three spoke in favor of retaining it, and one said that all statues should be removed. The opinion pages of the Star Democrat revealed a similar ratio. One Easton resident wrote in her letter to the editor, “I have lived most of my life oblivious to racism. Obvious racism was never directed at me because I’m white. I walked past statues and monuments and even confederate flags flying completely unaware of their meaning. Racism can be as subtle as a dirty look or a snide comment or as in my case, seeing but not understanding the statues that I’ve walked past my whole life.”

A public-information request revealed that of the nearly nine hundred people who contacted the county council about the statue directly, more than seven hundred of them advocated for its removal. Many wrote passionately about how much they had learned about a place they thought they knew, and how, like Councilman Pack, that knowledge had changed their opinion of the statue and its appropriateness on public property. So far this summer, there have been a half-dozen demonstrations outside the courthouse by those who support removal, including one organized immediately after the council voted 3–2 against the resolution; within thirty minutes, almost a hundred people had assembled, putting an end to the fiction that only outside agitators wanted the monument gone.

At that meeting on August 11th, Laura Price was joined by two of her Republican colleagues in voting against removing the statue: Chuck Callahan, who runs a local construction company, and Frank Divilio, a local insurance agent. They were, technically speaking, not in favor of keeping the monument; they were merely opposed to removing it. Collectively, they made a procedural case. Price argued that the resolution “should not have been introduced under our emergency order,” meaning while the pandemic procedures were in place, during which time the council had taken action on all sorts of other matters, from liquor licensing to the residency requirements for county employees.

Divilio and Callahan also invoked the coronavirus pandemic, claiming that it had prevented enough public input. The Confederate monument was somehow both too trivial to consider during the pandemic, according to Price, and too serious to decide without further deliberation, according to two of her colleagues. “This is a big deal for a lot of people, and it’s a big deal for us to make such a historical decision on something that is one hundred and fifty years old,” Callahan said, of a statue that is a hundred and four years old. Although he himself had voted to keep it four years earlier, during his previous term, now he said, “I don’t think it should be the council’s decision.”

At one point, Callahan lamented that “nobody’s here that’s on that statue,” adding, “There’s eighty-four names on that statue, and they can’t stand in front of us and tell us what their thoughts are.” Apparently, the opinion of Confederate ghosts mattered more than those of living residents who had spent the summer sharing their views. Some observers pointed out that the problem did not actually seem to be the lack of comments but, rather, the lack of comments in favor of keeping the statue. (Divilio and Price denied that this was their reasoning. Callahan did not respond to a request for comment.)

Councilman Divilio, who had previously proposed a “unity statue” to replace the Confederate monument, now claimed that the broader public should decide its future, via a ballot question. “It’s time for us to put it back to the community,” he said. Because of statewide deadlines, a ballot question could not appear until 2022—and chances are that it would not appear even then. Maryland has strict rules about what kinds of questions can appear on ballots, and a straw poll of this sort is generally prohibited. This year, the pandemic; two years from now, the impossibility of putting the matter to public vote. “I’d like to push it down the road a little bit,” Callahan said.

Not taking action is a form of action. It preserves the status quo; in this case, it preserves a Confederate monument on public property. The “Talbot Boys” statue remains for the same reason it was erected in the first place: not because it is historically accurate or represents the will of the majority but because powerful people support it and they can afford to ignore those of us who do not. The letters calling for its removal have continued, as have the protests, prompting the council to conduct their meetings virtually rather than continuing to convene in person.

Some say that change is coming too quickly, or that it is coming from elsewhere. After the council declined to act, Michelle Ewing, the secretary of the Mid Shore League of Republican Women, wrote a letter to the Star Democrat thanking Price, Divilio, and Callahan for resisting “calls from the extremist/racist BLM, Antifa, NAACP and ACLU to remove a monument because it offends some people.” She added, “The rioting, lawlessness, looting, arson, murder and extreme intimidation to defund our police, take a knee, submit to race baiters or else, has to end.”

But the call to remove the statue didn’t originate outside Talbot County, and, whatever is happening elsewhere in the country, the local protests have taken the form of handmade signs, banjo players, bucket drums, noisemakers, banners, and chants—all on the public grounds of the courthouse itself. Even claiming that local opposition to the monument is a recent development concedes too much to the statue’s defenders. In reality, there are those who saw the danger of Confederate tributes long before the current debate, including Frederick Douglass himself. Speaking at Arlington Cemetery on Decoration Day, just a few years after the Civil War ended, Douglass said, “We are sometimes asked, in the name of patriotism, to forget the merits of this fearful struggle, and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life and those who struck to save it—those who fought for slavery, and those who fought for liberty and justice.”

For more than a hundred years, that forgetfulness has been enshrined in bronze and granite at the very courthouse square where Douglass was once jailed. I know the dangers of such false remembrances because of how they deformed my own understanding of local history when I was a child, and I see it in so many of the historically inaccurate arguments offered by those who defend the Confederate statue today—most heartbreakingly, in those who argue that if the Confederate statue is removed then Douglass should be, too.

The twin of the “Talbot Boys,” in Lake Charles, Louisiana, was also the subject of protests this summer. In August, local authorities voted to keep it up. Two weeks later, Hurricane Laura’s hundred-and-thirty-mile-per-hour winds ripped that statue from its pedestal, leaving it crumpled on the ground. Hurricanes find their way to the Eastern Shore, too, but Talbot County does not need an act of God. It needs, from just one more council member, an act of conscience.

Originally appeared on The New Yorker

About

According to Pew Research, 77 percent of The New Yorker’s audience hold left-of-center political values, while 52 percent of those readers hold “consistently liberal” political values.

USDE’s Analysis

This piece directly speaks towards a white, and black supremacy equally in regards to the recent protests across America that’s portraying a black-based agenda and supremacy over white. The removal of such statues would not necessarily be enough for such an organization as the political agenda of “BLM” is speculated to be much deeper; emphasis that the white race are racially segregating the black race if one is not supporting their organization.