About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

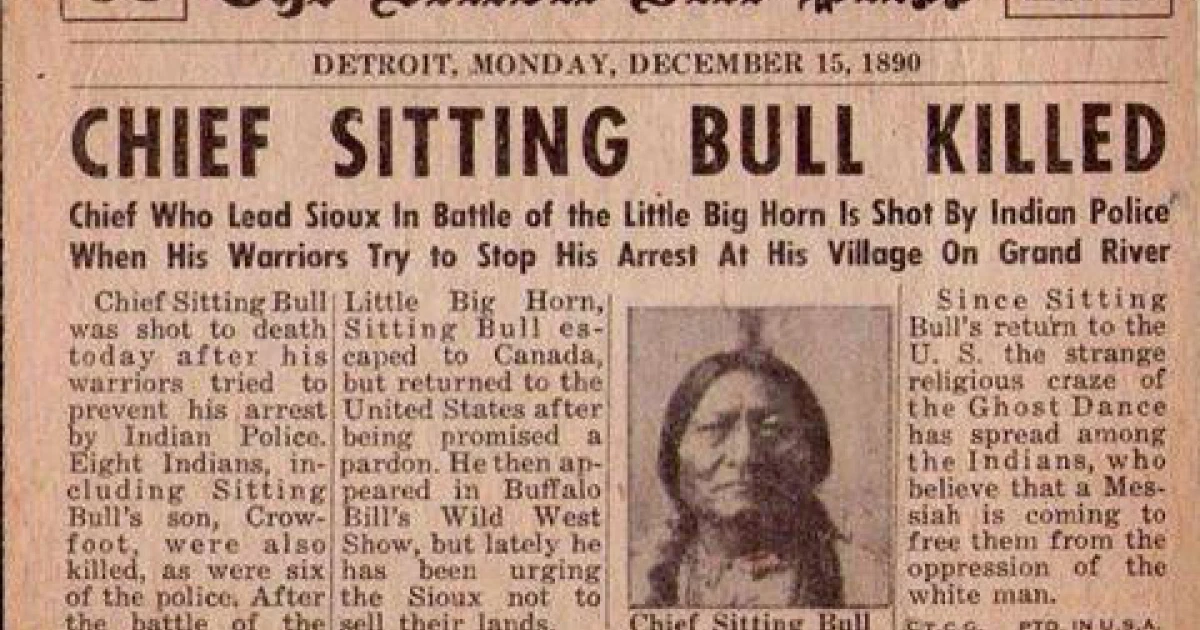

Annotation: Sitting Bull was the Indian chief of the Dakota Sioux. In 1876, his people were driven from the Black Hills reservation. In response, they took up arms against the whites to protect the right to remain on their lands. Sitting Bull and his people defeated a group of Custer’s men that had been sent in advance of Gen. Alfred Terry’s men (Gen. Terry’s command was one column of Gen. Custer’s brigade).

Sitting Bull and his people embraced the Ghost Dance movement started by Wovoka. The fervor of the movement had instilled great fear in white people, as they believed the excitement of the dance was in preparation for future hostilities directed at them. Performing the dance was illegal on the reservation, and Major James McLaughlin visited Sitting Bull to convince him and his followers to abandon the dance to ensure their safety. Sitting Bull was defiant and refused. U.S. authorities confronted him, and he was eventually shot and killed by two Sioux policemen. Shortly after, the massacre at Wounded Knee occurred, partly in response to the death of Sitting Bull and partly because of the upheaval that the Ghost Dance caused.

Document: An Account of Sitting Bull’s Death

by James McLaughlin, Indian Agent at Standing Rock Reservation (1891)

—————

Office of Indian Rights Association, 1305 Arch Street, Philadelphia, Jan. 19th, 1891.

The following graphic and reliable account of the death of Sitting Bull and of the circumstances attending it will be read with interest by many readers. It was written by Major James McLaughlin, who for many years has occupied the post of Indian Agent at Standing Rock, Dakota, and was sent to us by my request. Agent McLaughlin is a good example of what an Indian Agent should be: experienced, faithful, and courageous. The report which he has so kindly sent us is worthy of especial attention at this time. It proves that while there are bad Indians there are also good ones. The unostentatious courage and fidelity of the Indian police, who did not hesitate to sacrifice their lives in the service of a Government not of their own race, is worthy of remembrance.

Herbert Welsh, Cor. Sec’y I. R. A.

—————

United States Indian Service, Standing Rock Agency, North Dakota, Jan. 12th, 1891.

My Dear Mr. Welsh,

Your letter of the 16th ultimo was duly received, and should have been answered earlier, but I have not had a moment to spare since its receipt.

The newspaper reports regarding the arrest and death of Sitting Bull have nearly all been ridiculously absurd, and the following is a statement of the facts:

I was advised by a telegram from the Indian Office, dated Nov. 14th, 1890, that the President had directed the Secretary of War to assume a military responsibility for the suppression of any threatened outbreak among the Sioux Indians, and on December 1st, 1890, another telegram instructed me that as to all operations intended to suppress any outbreak by force, to “co-operate with and obey the orders of the military officers commanding on the reservation.” This order made me subject to the military authorities, and to whom I regularly reported the nature of the “Messiah Craze” and the temper of the Indians of the reservation.

As stated in my letter to you, dated November 25th last, the Messiah doctrine had taken a firm hold upon Sitting Bull and his followers, and that faction strove in every way to engraft it in the other settlements; but by close watching and activity of the police we prevented it from getting a start in any of the settlements outside of the upper Grand River, which districts were largely composed of Sitting Bull’s old followers, over whom he always exerted a baneful influence, and in this craze they fell easy victims to his subtlety, and believed blindly in the absurdities he preached of the Indian millennium. He promised them the return of their dead ancestors and restoration of their old Indian life, together with the removal of the white race; that the white man’s gunpowder could not throw a bullet with sufficient force in future to injure true believers; and even if Indians should be killed while obeying this call of the Messiah, they would only be the sooner united with their dead relatives, who were now all upon the earth (having returned from the clouds), as the living and dead would be reunited in the flesh next spring. You will readily understand what a dangerous doctrine this was to get hold of a superstitious and semi-civilized people, and how the more cunning “medicine men” could impose upon the credulity of the average uncivilized Indian.

This was the status of the Messiah craze here on November 16th, when I made a trip to Sitting Bull’s camp, which is forty miles south-west of Agency, to try and get Sitting Bull to see the evils that a continuation of the Ghost dance would lead to, and the misery that it would bring to his people. I remained over night in the settlement and visited him early next morning before they commenced the dance, and had a long and apparently satisfactory talk with him, and made some impression upon a number of his followers who were listeners, but I failed in getting him to come into the Agency, where I hoped to convince him by long argument. Through chiefs Gall, Flying-By and Gray Eagle, I succeeded in getting a few to quit the dance, but the more we got to leave it the more aggressive Sitting Bull became so that the peaceable and well-disposed Indians were obliged to leave the settlement and could not pass through it without being subjected to insult and threats. The “Ghost Dancers” had given up industrial pursuits and abandoned their houses, and all moved into camp in the immediate neighborhood of Sitting Bull’s house, where they consumed their whole time in the dance and the purification vapor baths preparing for same, except on every second Saturday, when they came to the Agency for their bi-weekly rations.

Sitting Bull did not come into the Agency for rations after October 25th, but sent members of his family, and kept a bodyguard when he remained behind while the greater portion of his people were away from the camp; this he did to guard against surprise in case an attempt to arrest him was made. He frequently boasted to Indians, who reported the same to me, that he was not afraid to die and wanted to fight, but I considered that mere idle talk and always believed that when the time for his arrest came and the police appeared in force in his camp, with men at their head whom he knew to be determined, that he would quietly accept the arrest and accompany them to the Agency, but the result of the arrest proved the contrary. Since the Sioux Commission of 1889 (the Foster, Crook and Warner Commission) Sitting Bull has behaved very badly, growing more aggressive steadily, and the Messiah doctrine, which united so many Indians in common cause, was just what he needed to assert himself as “high priest,” and thus regain prestige and former popularity among the Sioux by posing as the leader of disaffection.

He being in open rebellion against constituted authority, was defying the Government, and encouraging disaffection, made it necessary that he be arrested and removed from the reservation, and arrangements were perfected for his arrest on December 6th, and everything seemed favorable for its accomplishment without trouble or bloodshed at that time; but the question arose as to whether I had authority to make the arrest or not, being subject to the military, to settle which I telegraphed to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs on December 4th, and on the 5th received a reply which directed me to make no arrests whatever, except under orders of the military, or upon an order from the Secretary of the Interior. My reason for desiring to make the arrest on December 6th, was that it could be done then with the greater assurance of success and without alarming the Indians to any great extent, as the major portion of them would have been in for rations at the Agency, forty miles distant from where the arrest would have been made, and I also foresaw, from the movements of the military, that the order for his arrest would soon be issued, and that another ration day (two weeks more) would have to elapse before it could be so easily accomplished.

On December 12th the following telegram was received by the Post Commander of Fort Yates, who furnished me with a copy:

Headquarters, Department of Dakota St. Paul, Minn. December 12th, 1890To Commanding Officer, Fort Yates, North Dakota:

The Division commander has directed that you make it your especial duty to secure the person of Sitting Bull. Call on Indian Agent to cooperate and render such assistance as will best promote the purpose in view. Acknowledge receipt, and if not perfectly clear, report back. By command of General Ruger.

(Signed) M. Barber, Assistant Adjutant General

Upon receipt of the foregoing telegram the Post Commander sent for me, and held a consultation as to the best means to affect the desired arrest. It was contrary to my judgment to attempt the arrest at any time other than upon one of the bi-weekly ration days when there would be but a few Indians in Sitting Bull’s neighborhood, thus lessening the chances of opposition or excitement of his followers. The Post Commander saw the wisdom of my reasoning, and consented to defer the arrest until Saturday morning, December 20th, with the distinct understanding, however, that the Indian police keep Sitting Bull and his followers under strict surveillance to prevent their leaving the reservation, and report promptly any suspicious movements among them.

Everything was arranged for the arrest to be made on December 20th; but on December 14th, at 4 P.M., a policeman arrived at the Agency from Grand River, who brought me a letter from Lieutenant of Police Henry Bull Head, the officer in charge of the force on Grand River, stating that Sitting Bull was making preparations to leave the reservation; that he had fitted his horses for a long and hard ride, and that if he got the start of them, he being well mounted, the police would be unable to overtake him, and he, therefore, wanted permission to make the arrest at once. I had just finished reading Lieut. Bull Head’s letter, and commenced questioning the courier who brought it, when Col. Drum, the Post Commander, came into my office to ascertain if I had received any news from Grand River. I handed him the letter which I had just received, and after reading it, he said that the arrest could not be deferred longer, but must be made without further delay; and immediate action was then decided upon, the plan being for the police to make the arrest at break of day the following morning, and two troops of the 8th Cavalry to leave the post at midnight, with orders to proceed on the road to Grand River until they met the police with their prisoner, whom they were to escort back to the post; they would thus be within supporting distance of the police, if necessary, and prevent any attempted rescue of Sitting Bull by his followers. I desired to have the police make the arrest, fully believing that they could do so without bloodshed, while, in the crazed condition of the Ghost Dancers, the military could not; furthermore, the police accomplishing the arrest would have a salutary effect upon all the Indians, and allay much of the then existing uneasiness among the whites. I, therefore, sent a courier to Lieut. Bull Head, advising him of the disposition to be made of the cavalry command which was to cooperate with him, and directed him to make the arrest at daylight the following morning.

Acting under these orders, a force of thirty-nine policemen and four volunteers (one of whom was Sitting Bull’s brother-in-law, “Gray Eagle”) entered the camp at daybreak on December 16th, proceeding direct to Sitting Bull’s house, which ten of them entered, and Lieut. Bull Head announced to him the object of their mission. Sitting Bull accepted his arrest quietly at first, and commenced dressing for the journey to the Agency, during which ceremony (which consumed considerable time) his son, “Crow Foot,” who was in the house, commenced berating his father for accepting the arrest and consenting to go with the police; whereupon he (Sitting Bull) got stubborn and refused to accompany them.

By this time he was fully dressed, and the policemen took him out of the house; but, upon getting outside, they found themselves completely surrounded by Sitting Bull’s followers, all armed and excited. The policemen reasoned with the crowd, gradually forcing them back, thus increasing the open circle considerably; but Sitting Bull kept calling upon his followers to rescue him from the police; that if the two principal men, “Bull Head” and “Shave Head,” were killed the others would run away, and he finally called out for them to commence the attack, whereupon “Catch the Bear” and “Strike the Kettle,” two of Sitting Bull’s men, dashed through the crowd and fired. Lieut. “Bull Head” was standing on one side of Sitting Bull and 1st Sergt. “Shave Head” on the other, with 2d Sergt. “Red Tomahawk” behind, to prevent his escaping; “Catch the Bear’s ” shot struck Bull Head in the right side, and he instantly wheeled and shot Sitting Bull, hitting him in the left side, between the tenth and eleventh ribs, and “Strike the Kettle’s” shot having passed through Shave Head’s abdomen, all three fell together. “Catch the Bear,” who fired the first shot, was immediately shot down by private of police “Lone Man,” and the fight then became general; in fact, a hand-to-hand conflict; forty-three policemen and volunteers against about one hundred and fifty crazed Ghost Dancers.

The fight lasted about half an hour, but all the casualties, except that of Special Policeman John Armstrong, occurred in the first few minutes. The police soon drove the Indians from around the adjacent buildings, and then charged and drove them into the adjoining woods, about forty rods distant, and it was in this charge that John Armstrong was killed by an Indian secreted in a clump of brush. During the fight women attacked the police with knives and clubs, but in every instance they simply disarmed them and placed them under guard in the houses near by until the troops arrived, after which they were given their freedom. Had the women and children been brought into the Agency there would have been no stampede of the Grand River people; but the men, realizing the enormity of the offence they had committed by attacking the police, as soon as their families joined them, fled up Grand River, and then turned south to the Morian and Cheyenne Rivers.

The conduct of the Indian police upon that occasion cannot be too highly commended. The following is an extract of the official report of E. G. Fechet, Captain 8th Cavalry, who commanded the detachment of troops sent to Grand River:–

“I cannot too strongly commend the splendid courage and ability which characterized the conduct of the Indian police commanded by Bull Head and Shave Head throughout the encounter. The attempt to arrest Sitting Bull was so managed as to place the responsibility for the fight that ensued upon Sitting Bull’s band, which began the firing. Red Tomahawk assumed command of the police after both Bull Head and Shave Head had been wounded, and it was he who, under circumstances requiring personal courage to the highest degree, assisted Hawk Man to escape with a message to the troops. After the fight, no demoralization seemed to exist among them, and they were ready and willing to cooperate with the troops to any extent desired.”

The following is a list of the killed and wounded casualties of the fight:

Henry Bull Head, First Lieutenant of Police, died 82 hour after the fight. Charles Shave Head, First Sergeant of Police, died 25 hours after the fight. James Little Eagle, Fourth Sergeant of Police, killed in the fight. Paul Afraid-of-Soldiers, Private of Police, killed in the fight. John Armstrong, Special Police, killed in the fight. David Hawkman, Special Police, killed in the fight. Alexander Middle, Private of Police, wounded, recovering. Sitting Bull, killed, 56 years of age. Crow Foot (Sitting Bull’s son), killed, 17 years of age. Black Bird, killed, 43 years of age. Catch the Bear, killed, 44 years of age. Spotted Horn Bull, killed, 56 years of age. Brave Thunder, No. 1, killed, 46 years of age. Little Assiniboine, killed, 44 years of age. Chase Wounded, killed, 24 years of age. Bull Ghost, wounded, entirely recovered. Brave Thunder, No. 2, wounded, recovering rapidly. Strike the Kettle, wounded, now at Fort Sully, a prisoner.

This conflict, which cost so many lives, is much to be regretted, yet the good resulting therefrom can scarcely be overestimated, as it has effectually eradicated all seeds of disaffection sown by the Messiah Craze among the Indians of this Agency, and has also demonstrated to the people of the country the fidelity and loyalty of the Indian police in maintaining law and order on the reservation. Everything is now quiet at this Agency, and good feeling prevails among the Indians, newspaper reports to the contrary notwithstanding. No Indians have left this Agency since the stampede of December 15th, following the conflict with the police, and no others will. There were three hundred and seventy-two men, women and children left at that time, of whom about one hundred and twenty are males over sixteen years of age, and of whom two hundred and twenty-seven are now prisoners at Fort Sully, and seventy-two are reported to have been captured at Pine Ridge Agency some time ago.

With kind regards,

I have the honor to be, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

James McLaughlin, Indian Agent

—————

Mr. Herbert Welsh Philadelphia, Pa.