About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

The fight was for the continent. The strategy embraced the lines from Boston to the mouth of the Chesapeake, from Montreal even to Charleston. Montgomery’s invasion of Canada, although St. John’s and Montreal were taken, failed before Quebec, and the retreat of the American forces gave Burgoyne the base for his comprehensive campaign. Howe had been compelled to give up New England, which contained nearly one-third of the population and strength of the colonies. The center of attack and of defense was the line of New York and Philadelphia. From their foothold at New York, on the one hand, and Montreal on the other, the British commanders aimed to grind the patriots of the Mohawk valley between the upper and nether mill stones. The design was to cut New England off from the other States, and to seize the country between the Hudson and Lake Ontario as the vantage ground for sweeping and decisive operations. This was the purpose of the wedge which Burgoyne south to drive through the heart of the Union. In the beginning of that fateful August, Howe held all the country about New York, including the islands, and the Hudson up to Peekskill; the British forces also commanded the St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario, and their southern shores, finding no opposition north of the Mohawk and Saratoga lake. The junction of Howe and Burgoyne would have rendered their armies masters of the key to the military position. This strip of country from the Highlands of the Hudson to the head of the Mohawk was the sole shield against such concentration of British power. Once lost it would become a sword to cut the patriots into fragments. They possessed it by no certain tenure. Two months later Governor Clinton and General Putnam lost their positions on the Hudson. Thus far Burgoyne’s march had been one of conquest. His capture of Ticonderoga had startled the land. The frontier fort at the head of the Mohawk was to cost him the column on whose march he counted so much.

The corps before Fort Stanwix was formidable in every element of military strength. The expedition with which it was charged was deemed by the war secretary at Whitehall of the first consequence, and it had received as marked attention as any army which King George ever let loose upon the colonists. For its leader Lieutenant-Colonel Barry St. Leger had been chosen by the king himself, on Burgoyne’s nomination. He deserved the confidence, if we judge by his advance, by his precautions, by his stratagem at Oriskany, and the conduct of the siege, up to the panic at the rumor that Arnold was coming. In the regular army of England he became an ensign in 1756, and coming to America the next year he had served in the French war, and learned the habits of the Indians, and of border warfare. In some local sense, perhaps as commanding this corps, he was styled a brigadier. His regular rank was Lieutenant-Colonel of the thirty-fourth regiment. In those days of trained soldiers it was a marked distinction to be chosen to select an independent corps on important service. A wise commander, fitted for border war, his order of march bespeaks him. Skillful in affairs, and scholarly in accomplishments, his writing prove him. Prompt, tenacious, fertile in resources, attentive to detail, while master of the whole plan, he would not fail where another could have won. Inferior to Se. Leger in rank, but superior to him in natural powers and personal magnetism, was Joseph Brant — Thayendanegea — chief of the Mohawks. He had been active in arraying the six Nations on the side of King George, and only the Oneidas and Tuscaroras had refused to follow his lead. He was not thirty-five years of age; in figure the ideal Indian, tall and spare and lithe and quick; with all the genius of his tribe, and the training gained in Connecticut schools, and in the family of Sir William Johnson; he had been a lion in London, and flattered at British headquarters in Montreal. Among the Indians he was preeminent, and in any circle he would have been conspicuous.

As St. Leger represented the regular army of King George, and brant the Indian allies, Sir John Johnson led the regiments which had been organized from the settlers in the Mohawk Valley. He had inherited from his father, Sir William, the largest estate held on the continent by any individual, William Penn excepted. He had early taken sides with the king against the colonists, and having entered into a compact with the patriots to preserve peace and remain at Johnstown, he had violated his promise, and fled to Canada. He came now with a sense of personal wrong, to recover his possessions and to resume the almost royal sway which he had exercised. He at this time held a commission as colonel in the British army, to raise and command forces raised among the royalists of the valley. Besides these was Butler, — John Butler, a brother-in-law of Johnson; lieutenant-colonel by rank, rich and influential in the valley, familiar with the Indians and a favorite of them, shrewd and daring and savage, already the father of that son Walter, who was to be the scourge of the settlers, and with him to render ferocious and bloody the border war. He came from Niagara, and was now in command of Tory rangers.

The forces were like the leaders. It has been the custom to represent St. Leger’s army as a “Motley crowd.” On the contrary it was a picked force, especially designated by orders from headquarters in Britain. He enumerates his “artillery, the thirty-fourth and the King’s regiment, with the Hessian riflemen and the whole corps of Indians,” with him, while his advance, consisting of a detachment under Lieutenant Bird, had gone before, and “the rest of the army, led by Sir John Johnson,” was a day’s march in the rear. Johnson’s whole regiment was with him, together with Butler’s Tory rangers, with at least one company of Canadians. The country from Schoharie, westward, had been scoured of royalists to add to this column. For such an expedition, the force could not have been better chosen. The pet name of the “King’s regiment” is significant. The artillery was such as could be carried by boat, and adapted to the sort of war before it. It had been especially designated from Whitehall. The Hana Chaseurs were trained and skillful soldiers. The Indians were the terror of the land. The Six Nations had joined the expedition in full force except the Oneidas and the Tuscaroras. With the latter tribes the influence of Samuel Kirkland had overborne that of the Johnson’s, and the Oneidas and the Tuscaroras where by their peaceful attitude more than by hostility useful to Congress to the end. The statement that two thousand Canadians accompanied St. Leger as axe men is no doubt an exaggeration; but, exclusive of such helper s and of noncombatants, the corps counted not less than seventeen hundred fighting men. King George could not then have sent a column better fitted for its task, or better equipped, or abler led, or more intent on achieving all that was imposed upon it. Leaving Montreal, it stated on the nineteenth of July from Buck Island, its rendezvous at the entrance of Lake Ontario. It had reached Fort Stanwix without the loss of a man, as if on a summer’s picnic. It had come through in good season. Its chief never doubted that he would make quick work with the Fort. He had even cautioned Lieutenant Bird who led the advance, lest he should rise the seizure with his unaided detachment. When his full force appeared, his faith was sure that the fort would “fall without a single shot.” So confident was he that he sent a dispatch to Burgoyne on the fifth of August, assuring him that the fort would be his directly, and they would speedily meet as victors at Albany. General Schuyler had in an official letter expressed a like fear.

St. Leger was therefore surprised as well as annoyed by the news that the settlers on the Mohawk had been aroused, and were marching in haste to relieve the fort. He found that his path to join Burgoyne was to be contested. He watched by skillful scouts the gathering of the patriots; their quick and somewhat irregular assembling; he knew of their march from Fort Dayton, and their halt at Oriskany. Brant told him that they advanced, as brave, untrained militia, without throwing out skirmishers, and with Indian guild the Mohawk chose the pass in which an ambush should be set for them. The British commander guarded the way for several miles from his position by scouts within speaking distance of each other. He knew the importance of his movement, and he was guilty of no neglect.

From his camp at Fort Stanwix St. Leger saw all, and directed all. Sir John Johnson led the force thrown out to meet the patriots, with Butler as his second, but Brant was its controlling head. The Indians were most numerous: “the whole corps, ” a “Large body,” St. Leger testifies. And with the Indians he reports were “some troops.” The presence of Johnson, and of Butler, as well as of Claus and Watts, of Captains Wilson, Hare and McDonald, the chief royalists of the valley, proves that their followers were in the fight. Butler refers to the New Yorkers whom we know as Johnson’s Greens, and the Rangers, as in the engagement in large numbers. St. Leger was under the absolute necessity of preventing the patriot force from attaching his successfully. He could not do less than send every available man out to meet it. Quite certainly the choicest of the army were taken from the dull duty of the siege for this critical operation. They left camp at night and lay above and around the ravine at Oriskany, in the early morning of the sixth of August. They numbered not less than twelve hundred men under chosen cover.

The coming of St. Leger had been known for weeks. Burgoyne had left Montreal in June, and the expedition by way of Lake Ontario, as the experience of a hundred years prophesied, would respond to his advance. Colonel Gansevoort had appealed to the Committee of Safety for Tryon county, for help. Its chairman was Nicholas Herchkeimer, (known to us as Herkimer,) who had been appointed a brigadier-general by congress in the preceding autumn. (His commission by the New York convention bears the date of September 5, 1776.) His family was large, and it was divided in the contest. A brother was captain with sire John Johnson, and a brother-in-law was one of the chief of the loyalists. He was now forty-eight years of age, short, slender, of dark complexion, with black hair and bright eyes. He had German pluck and leadership, but he had also German caution and deliberation. He foresaw the danger, and had given warning to General Schuyler at Albany. On the seventeenth of July had had issued a proclamation, announcing that the enemy, two thousand strong, was at Oswego, and that as soon as he could approach, every male person being in health, and between sixteen and sixty years of age, should immediately be ready to march against him. Tryon county had strong appeals for help also from cherry Valley and Unadilla; General Herkimer had been southward at the close of June to check operations of the Tories and Indians under Brant; and Frederick Sammons had been sent on a scouting expedition to the Black river country, to test the rumors that an invasion from Canada was to be made from that direction. The danger from these directions delayed and obstructed recruiting for the column against St. Leger. The stress was great, and Herkimer was bound to keep watch south and north as well as west. He waited only to learn where need was greatest, and he went thither. On the thirtieth of July, a letter from Thomas Spencer, a half-breed Oneida, read on its way to General Schuyler, made known the advance of St. Leger. Herkimer’s order was promptly issued, and soon brought in eight hundred men. They were nearly all by blood Germans and low Dutch, with a few of other nationalities. The roster, so far as can now be collected, indicates the presence of persons of English, Scotch, Irish, Welsh, and French blood, but these are exceptions, and the majority of the force was beyond question German. They gathered from their farms and clearings, carrying their equipments with the. They met at Fort Dayton, near the mouth of the West Canada Creek. This post was held at the time by a part of colonel Wesson’s Massachusetts regiment, also represented in the garrison at Fort Stanwix. The little army was divided into four regiments or battalions. The first, which Herkimer had once commanded, was now led by Colonel Ebenezer Cox, and was from the district of Canajoharie; of the second, from Palatine, Jacob Klock was colonel; the third was under Colonel Frederick Visscher, and came from Mohawk; the fourth, gathered from German flats and Kingsland, Peter Bellinger commanded.

Counsels were divided whether they should await further accessions, or hasten to Fort Stanwix Prudence prompted delay. St. Leger’s force was more than double that of Herkimer; it might be divided, and while one-half occupied the patriot column, the Indians under Tory lead might hurry down the valley, gathering reinforcements while they ravaged the homes of the patriots. The blow might come from Unadilla, where Brant had been as late as the early part of that very July. Herkimer, at Fort Dayton, was in position to turn in either direction. But the way of the Mohawk was the natural and traditional warpath. The patriots looked to Fort Stanwix as their defense. They started on the fourth, crossed the Mohawk where is not Utica, and reached Whitestown on the fifth. Here it was probably that a band of Oneida Indians joined the column. From this point or before Herkimer sent an express to Colonel Gansevoort arranging cooperation. He was to move forward when three cannon signaled that aid was ready. The signal was not heard; the messenger had been delayed. His chief advisors, including Colonel Cox and Paris, the latter a member of the Committee of Safety, urged quicker movement. Fort Stanwix might fall while they were delaying, and the foe could then turn upon them. Herkimer was taunted as a coward and a Tory. His German phlegm was stirred. He warned his impatient advisers that they would be the first in the face of the enemy to flee. He gave the order “march on!” Apprised of the ambuscade, his courage which had been assailed prevented the necessary precautions.

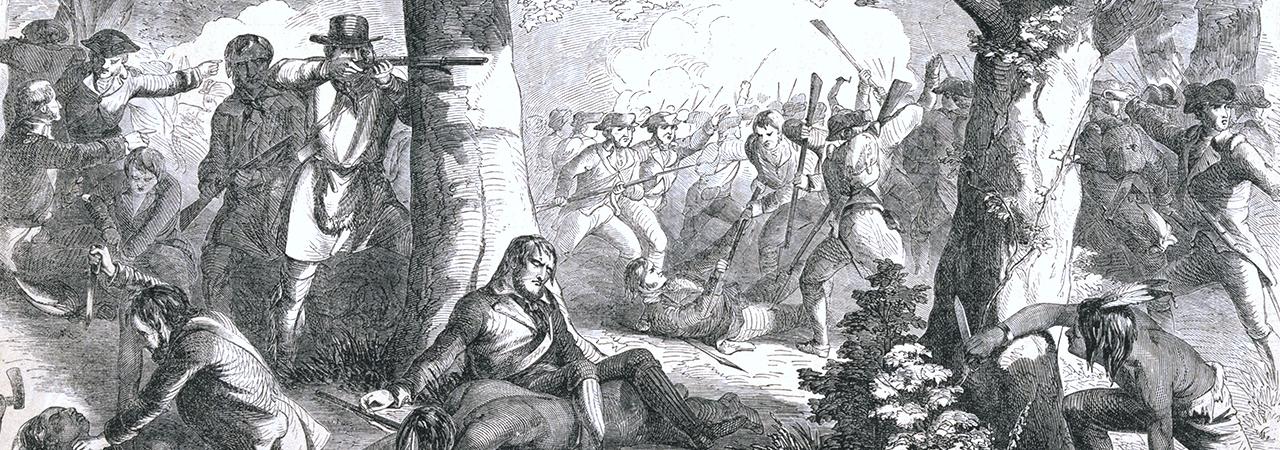

He led his little band on. If he had before been cautious, now he was audacious. His course lay on the south side of the river, avoiding its bends, where the country loses the general level which the rude road sought to follow, when it could be found. For three or four miles hills rose upon valleys, with occasional gullies. The trickling springs and the spring freshets had cut more than one ravine where even in the summer, the water still moistened the earth. These run toward the river, from southerly toward the north. Corduroy roads had been constructed over the marches. For this was the line of such travel as sought Fore Stanwix and the river otherwise than by boat. Herkimer had come to one of the deepest of these ravines, ten or twelve rods wide, running narrower up to the hills at the south, and broadening toward the Mohawk into the flat bottom land. Where the forests were thick, where the rude roadway ran down into the march, and the ravine closed like a pocket, he pressed his way. Not in soldierly order, not watching against the enemy, but in rough haste, the eight hundred marched. They reached the ravine at ten in the morning. The advance had gained the higher ground. Then as so often, the woods became alive. Black eyes flashed from behind every tree. Rifles blazed from a thousand unexpected coverts. The Indians rushed out hatchet in hand, decked in paint and feather. The brave band was checked. It was cut in two. The assailants aimed first of all to seize the supply train. Colonel Visscher, who commanded its rear guard, showed his courage before and after and doubtless fought well here, as the best informed descendants of other heroes of the battle believe. But his regiment, driven northward toward the river, was cut up or in great part captured with the supplies and ammunition. In the ravine and just west of it, Herkimer rallied those who stood with him. Back to back, shoulder to shoulder, they faced the foe. Where shelter could be had two stood tighter, so that one might fire while the other loaded. Often the fight grew closer, and the knife ended the personal contest. Eye to eye, hand to hand, this was a fight of men. Nerve and brawn and muscle were the price of life. Rifle and knife, spear and tomahawk, were the only weapons, or the clubbed butt of the rifle. It was not a test of science, not a weighing of enginery, not a measure of caliber not an exhibition of choices mechanism. Men stood against death, and death struck at them with the simplest implements. Homer sings of chariots and shields. Here were not such helps, no such defenses. Fort or earthworms, barricades or abattis, there were none. The British force had chosen its ground. Two to one it must have been against the band which stood and fought in that pass, forever glorious. Herkimer, early wounded and his horse shot under him, sat on his saddle beneath a beech tree, just where the hill rises at the west a little north of the center of the ravine, calmly smoking a pipe while ordering the battle. He was urged to retire from so much danger; his reply is the eloquence of a hero: “I will face the enemy.”

Meanwhile, Gen. Nathanael Greene’s column on Limekiln Road caught up with the American forces at Germantown. Its vanguard engaged the British pickets at Luken’s Mill and drove them off after a savage skirmish. Adding to the heavy fog that already obscured the Americans’ view of the enemy was the smoke from cannons and muskets, and Greene’s column was thrown into disarray and confusion. One of Greene’s brigades, under the command of Gen. Stephen, veered off course and began following Meetinghouse Road instead of rendezvousing at Market Square with the rest of Greene’s forces. The wayward brigade collided with the rest of American Gen. Wayne’s brigade and mistook them for the redcoats. The two American brigades opened heavy fire on each other, became badly disorganized, and fled. The withdrawal of Wayne’s reserve New Jersey Brigade, which had suffered heavy casualties attacking the Chew house, left Conway’s left flank unsupported.

The ground tells the story of the fight. General Herkimer was with the advance, which had crossed the ravine. His column stretched out for nearly half a mile. Its head was a hundred rods or more west of the ravine, his rear guard reached as far east of it. The firing began from the hills into the gulf. Herkimer closed his line on its center, and in reaching that point his white horse was shot under him. The flag staff today on the hill marks his position. Then, as today, the hills curved like a cimeter, from the west to the east on the north side of the river. Fort Stanwix could not be seen, but it lay in the plain just beyond the gap in the hills, six miles distant. The Mohawk, from the mouth of the Oriskany, curves northward, so that here it is as far away in a right line, perhaps a mile in each case. The bottoms were marshy, as they yet are where the trees exclude the sun. Now the New York Central Railroad and the Erie Canal mark the general direction of the march of the patriots from their starting place hither. Then forests of beech and birch and maple and hemlock covered the land where now orchards and rich meadows extend, and grain fields are ripening for the harvest. Even the forests are gone, and the Mohawk and the hills and the ravine and “Battle Brook,” are the sole witnesses to confirm the traditions which have come down to us. The elms which fling their plumes to the sky are young successors to the knightly warriors who were once masters here. Through the forests Herkimer, from his elevation, could catch the general outlines of the battle. Some of his advance had fallen at the farthest point to which they had marched. Upon their left the enemy had appeared in force, and had closed up from the southward, and on the east side of the ravine. The patriots had been pushed to the north side of the road, away from the line which the corduroy still marks in the ravine, and those who fled sought the river. Skeletons have been found in the smaller ravine about two hundred rods west, and at the mouth of the Oriskany, an extent of a mile and a half; and gun barrels and other relics along the line of the Erie Canal, and down toward the river. These are witnesses of the battle. They mark the center here. Here gathered the brave militia without uniforms, in the garb of farmers, for their firesides and their homes, and the republic just born which was to be. Against them here, in the ravine, pursuing and capturing the rear guard on the east of the ravine or down in it, and thence toward the river, rushed from the forests, uniformed and well equipped, Johnson’s Greens, in their gay color, the German Chasseurs, Europe’s best soldiers, with picked men of British and Canadian regiments, and the Indian warriors decked in the equipments with which they made war brilliant. Some of this scene Herkimer saw; some of it extent of space and thickness of forest hid from his eye. But here he faced the enemy, and here he ordered the battle.

During the carnage a storm of wind and rain and lightning brought a respite. Old men preserve the tradition that in the path by which the enemy came a broad windfall was cut, and was seen for long years afterward. The elements caused only a short lull. In came at the thick of the strife a detachment of Johnson’s’ Greens; and they sought to appear reinforcements for the patriots. They paid dearly for the fraud, for thirty were quickly killed. Captain Gardenier slew three with his spear, one after the other. Captain Dillenback, assailed by three, brained one, shot the second and bayoneted the third. Henry Thompson grew faith with hunger, sat down on the body of a dead soldier, ate his lunch, and refreshed, resumed the fight. William Merckley, mortally wounded, to a friend offering to asset him, said: “Take care of yourself, leave me to my fate.” Such men could not be whipped. The Indians, finding they were losing many, became suspicious that their allies wished to destroy them, and fired on them, giving unexpected aid to the patriot band. Tradition relates that an Oneida maid, only fifteen years old, daughter of a chief, fought on the side of the patriots, firing her rifle, and shouting her battle cry. The Indians raised the cry of retreat, “Oonah! Oonah!” Johnson heard the firing of a sortie from the fort. The British fell back, after five hours of desperate fight. Herkimer and his gallant men held the ground.

The sortie from Fort Stanwix, which Herkimer expected, was made as soon as his messengers arrived. They were delayed, and yet got through at a critical moment. Colonel Willett made a sally at the head of two hundred and fifty men, totally routed two of the enemy’s encampments, and captured their contents, including five British flags. The exploit did not cost a single patriot life, while at least six of the enemy were killed and four made prisoners. It aided to force the British retreat from Oriskany. The captured flags were floated beneath the stars and stripes, fashioned in the fort from cloaks and shirts; and here for the first time the flag of the republic was raised in victory over British colors.

The sortie from Fort Stanwix, which Herkimer expected, was made as soon as his messengers arrived. They were delayed, and yet got through at a critical moment. Colonel Willett made a sally at the head of two hundred and fifty men, totally routed two of the enemy’s encampments, and captured their contents, including five British flags. The exploit did not cost a single patriot life, while at least six of the enemy were killed and four made prisoners. It aided to force the British retreat from Oriskany. The captured flags were floated beneath the stars and stripes, fashioned in the fort from cloaks and shirts; and here for the first time the flag of the republic was raised in victory over British colors.

The slaughter at Oriskany was terrible. St. Leger claims that four hundred of Herkimer’s men were killed and two hundred captures, leaving only two hundred to escape. No such number of prisoners was ever accounted for. The Americans admitted two hundred killed, one fourth of the whole army. St. Leger places the number of Indians killed, at thirty, and the like number wounded, including favorite chiefs and confidential warriors. It was doubtless greater, for the Senecas alone lost thirty-six killed, and in all the tribes twice as many must have been killed. St. Leger makes no account of any of his whites killed or wounded. Butler, however, mentions of New Yorkers (Johnson’s Greens) killed, Captain McDonald; Captain Watts dangerously wounded and one sabaltern. Of the Tory Rangers Captains Wilson and Hare (their chiefs after Butler) were killed. With such loss of officers, the death list of privates must have been considerable. The Greens alone lost thirty. In Britain it was believed as many of the British were killed by the Indians as by the militia. The loss of British and Indians must have approached a hundred and fifty killed. Eyewitnesses were found who estimated it as great as that of the Americans. The patriot dead included Colonel Cox, and his Lieutenant-Colonel Hunt, Majors Eisenlord, Van Slyck, Klapsattle and Belvin; and Captains Diefendorf, Crouse, Bowman, Dillenback, Davis, Pettingill, Helmer, Graves and Fox; with no less than four member of the Tryon county Committee of Safety, who were present as volunteers. They were Isaac Paris, Samuel Billington, John Dygert and Jacob Snell. Spencer, the Oneida, who gave the warning to the patriots, was also among the killed. The heads of the patriot organization in the valley were swept off. Herkimer’s glory is that out of such slaughter he snatched the substance of victory. In no other battle of the revolution did the ration of deaths rise so high. At Waterloo, the French loss was not in so large a ration to the number engaged, as was Herkimer’s at Oriskany; no did the allies suffer as much on that bloody field.

Frightful barbarities were wreaked on the bodies of the dead, and on the prisoners who fell into the hands of the Indians. The patriots held the field at the close of the fight, and were able to carry off their wounded. Among these was the brave and sturdy Herkimer, who was taken on a litter of boughs to his home, and after suffering the amputation of his leg, died on the sixteenth of August like a Christian hero. Of the dead some at least lay unburied until eighteen days later. Arnold’s column rendered to them that last service.

After the battle, Colonel Samuel Campbell, afterward conspicuous in Otsego county, became senior officer, and organized the shattered patriots, leading them in good order back to Fort Dayton. The night of the fight they bivouacked at Utica. Terrible as their losses had been, only sixteen days later Governor Clinton positively ordered them to join General Arnold on his expedition with one-half of each regiment. In his desperation, Sir John Johnson “proposed to march down the country with about two hundred men,” and Claus would have added Indians; but St. Leger disapproved of the suggestion. Only a raid could have been possible. The fighting capacity of St. Leger’s army was exhausted at Oriskany, and he knew it.

St. Leger’s advance was checked. His junction with Burgoyne was prevented. The rising of royalists in the valley did not occur. He claimed indeed the “completest victory” at Oriskany. He notified the garrison that Burgoyne was victorious at Albany, and demanded peremptorily the surrender of the fort; threatening that prolonged resistance would result in general massacre at the hands of the enraged Indians. Johnson, Claus and Butler issued an address to the inhabitants of Tryon county, urging them to submit, because “surrounded by victorious armies.” Colonel Gansevoort treated the summons as and insult, and held his post with sturdy steadiness.” The people of the valley sided with congress against the King. For sixteen days after Oriskany, St. Leger lay before Fort Stanwix, and heard more and more clearly the rumblings of fresh resistance from the valley.

Colonel Willett who led the gallant sortie, accompanied by Major Stockwell, risked no less danger on a mission through thickets and hidden foes, to inform General Schuyler at Albany of the situation. In a council of officers, bitter opposition arose to Schuyler’s proposal to send relief to Fort Stanwix, on the plea that it would weaken the army at Albany, the more important position. Schuyler was equal to the occasion, acting promptly, and with great energy. “Gentlemen,” said he, “I take the responsibility upon myself. Where is the brigadier who will command the relief? I shall beat up for volunteers tomorrow.” Benedict Arnold, then unstained by treason, promptly offered to lead the army. On the next day, August ninth, eight hundred volunteers were enrolled, chiefly of General Lauren’s Massachusetts brigade. General Israel Putnam ordered the regiments of Colonels Cortlandt and Livingston from Peekskill to join the relief “against those worse than infernals.” Arnold was to take supplies wherever he could get them, and especially not to offend the already unfriendly Mohawks. Schuyler enjoined upon him also “as the inhabitants of Tryon county were chiefly Germans, it might be well to praise their bravery at Oriskany, and ask their gallant aid in the enterprise.” Arnold reached Fort Dayton, and on the twentieth of August issued as commander-in-chief of the army of the United States of America on the Mohawk river, a characteristic proclamation, denouncing St. Leger as “a leader of a banditti of robbers, murderers and traitors, composed of savages of America and more savage Britons.” The militia joined him in great numbers. On the twenty-second, Arnold pushed forward, and on the twenty-fourth he arrived at Fort Stanwix. St. Leger had raised the siege and precipitately fled.

St. Leger had been frightened by rumors of the rapid advance of Arnold’s army. Arnold had taken pains to fill the air with them. He had sent to St. Leger’s camp a half-witted royalist, Hon. Yost Schuyler, to exaggerate his numbers and his speed. The Indians in camp were restive and kept tract of the army of relief. They badgered St. Leger to retreat, and threatened to abandon him. The raised the alarm, “they are coming!” and for the numbers of the patriots approaching, they pointed to the leaves of the forest.

On the twenty-second of August, while Arnold was yet at Utica, St. Leger fled. The Indians were weary; they had lost goods by Willett’s sortie; they saw no chance for spoils. Their chiefs killed at Oriskany beckoned them away. The began to abandon the ground, and to spoil the camp of their allies. St. Leger deemed his danger from them, if he refused to follow if he refused to follow their counsels, greater than from the enemy. He hurried his wounded and prisoners forward; he left his tents, with most of his artillery and stores, spoils to the garrison. His men threw away their packs in their flight. He quarreled with Johnson, and the Indians had to make peace between them. St. Leger indeed was helpless. The flight became a disgraceful rout. The Indians butchered alike prisoners and British who could not keep up, or become separated from the column. St. Leger’s expedition, as one of the latest became one of the most striking illustrations to the British of the risks and terrors of an Indian alliance.

The siege of Fort Stanwix was raised. The logic of the Battle of Oriskany was consummated. The whole story has been much neglected, and the best authorities on the subject are British. The battle is one of a series of events which constitute a chain of history as picturesque, as exciting, as heroic, as important, as ennoble any part of this or any other land.