About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Thomas Hutchinson

Governor of Massachusetts during early 1770s; instituted policies that prompted the Boston Tea Party

Charles Townshend

British member of Parliament who crafted the 1767 Townshend Acts

Parliament wasted little time invoking its right to “bind” the colonies under the Declaratory Act. The very next year, in 1767, it passed the Townshend Acts. Named after Parliamentarian Charles Townshend, these acts included small duties on all imported glass, paper, lead, paint, and, most significant, tea. Hundreds of thousands of colonists drank tea daily and were therefore outraged at Parliament’s new tax.

Fueled by their success in protesting the Stamp Act, colonists took to the streets again. Nonimportation Agreements were strengthened, and many shippers, particularly in Boston, began to import smuggled tea. Although initial opposition to the Townshend Acts was less extreme than the initial reaction to the Stamp Act, it eventually became far greater. The nonimportation agreements, for example, proved to be far more effective this time at hurting British merchants. Within a few years’ time, colonial resistance became more violent and destructive.

To prevent serious disorder, Britain dispatched 4,000 troops to Boston in 1768—a rather extreme move, considering that Boston had only about 20,000 residents at the time. Indeed, the troop deployment quickly proved a mistake, as the soldiers’ presence in the city only made the situation worse. Bostonians, required to house the soldiers in their own homes, resented their presence greatly.

Tensions mounted until March 5, 1770, when a protesting mob clashed violently with British regulars, resulting in the death of five Bostonians. Although most historians actually blame the rock-throwing mob for picking the fight, Americans throughout the colonies quickly dubbed the event the Boston Massacre. This incident, along with domestic pressures from British merchants suffering from colonial nonimportation agreements, convinced Parliament to repeal the Townshend Acts. The tax on tea, however, remained in place as a matter of principle. This decision led to more violent incidents.

In 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act, granting the financially troubled British East India Company an exclusive monopoly on tea exported to the American colonies. This act agitated colonists even further: although the new monopoly meant cheaper tea, many Americans believed that Britain was trying to dupe them into accepting the hated tax.

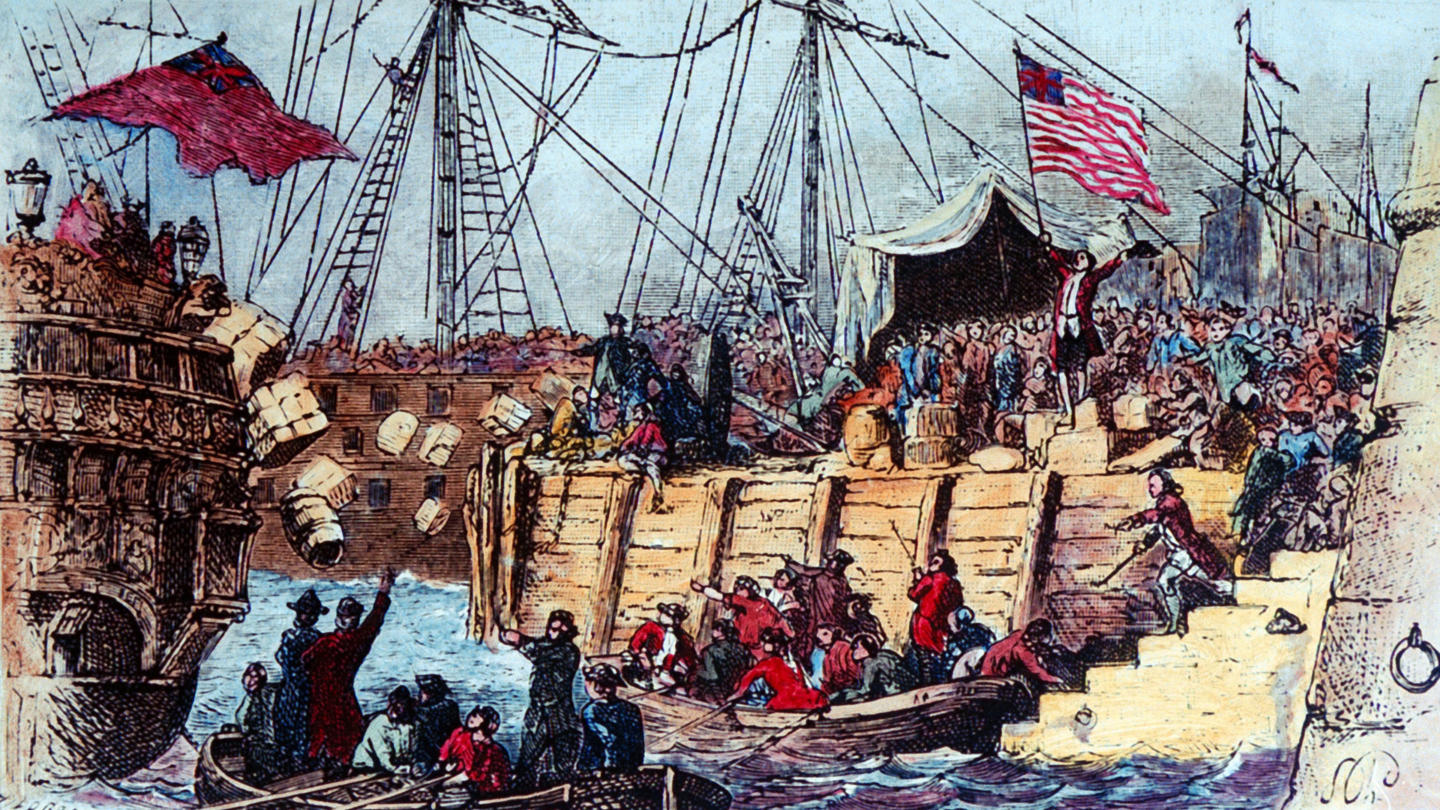

In response to the unpopular act, tea agents in many American cities resigned or canceled orders, and merchants refused consignments. In Boston, however, Governor Thomas Hutchinson resolved to uphold the law and ordered that three ships arriving in Boston Harbor be allowed to despoit their cargoes and that appropriate payment be made for the goods. This policy prompted about sixty men, including some members of the Sons Of Liberty, to board the ships on the night of December 16, 1773 (disguised as Native Americans) and dump the tea chests into the water. The event became known as the Boston Tea Party.

The dumping of the tea in the harbor was the most destructive act that the colonists had taken against Britain thus far. The previous rioting and looting of British officials’ houses over the Stamp Act had been minor compared to the thousands of pounds in damages to the ships and tea. Governor Hutchinson, angered by the colonists’ disregard for authority and disrespect for property, left for England. The “tea party” was a bold and daring step forward on the road to outright revolution.

The Tea Party had mixed results: some Americans hailed the Bostonians as heroes, while others condemned them as radicals. Parliament, very displeased, passed the Coercive Acts in 1774 in a punitive effort to restore order. Colonists quickly renamed these acts the Intolerable Acts.

Numbered among these Intolerable Acts was the Boston Port Bill, which closed Boston Harbor to all ships until Bostonians had repaid the British East India Company for damages. The acts also restricted public assemblies and suspended many civil liberties. Strict new provisions were also made for housing British troops in American homes, reviving the indignation created by the earlier Quartering Act, which had been allowed to expire in 1770. Public sympathy for Boston erupted throughout the colonies, and many neighboring towns sent food and supplies to the blockaded city.

At the same time the Coercive Acts were put into effect, Parliament also passed the Quebec Act. This act granted more freedoms to Canadian Catholics and extended Quebec’s territorial claims to meet the western frontier of the American colonies.