About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

The Battle of Perryville, also known as the Battle of Chaplin Hills, was fought on October 8, 1862, in the Chaplin Hills west of Perryville, Kentucky, as the culmination of the Confederate Heartland Offensive (Kentucky Campaign) during the American Civil War. Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg’s Army of Mississippi[5] won a tactical victory against primarily a single corps of Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s Union Army of the Ohio. The battle is considered a strategic Union victory, sometimes called the Battle for Kentucky, since Bragg withdrew to Tennessee soon thereafter. The Union retained control of the critical border state of Kentucky for the remainder of the war. On October 7, Buell’s army, in pursuit of Bragg, converged on the small crossroads town of Perryville in three columns. Union forces first skirmished with Confederate cavalry on the Springfield Pike before the fighting became more general, on Peters Hill, when the Confederate infantry arrived. Both sides were desperate to get access to fresh water. The next day, at dawn, fighting began again around Peters Hill as a Union division advanced up the pike, halting just before the Confederate line. After noon, a Confederate division struck the Union left flank—the I Corps of Maj. Gen. Alexander M. McCook—and forced it to fall back. When more Confederate divisions joined the fray, the Union line made a stubborn stand, counterattacked, but finally fell back with some units routed.[6]

Buell, several miles behind the action, was unaware that a major battle was taking place and did not send any reserves to the front until late in the afternoon. The Union troops on the left flank, reinforced by two brigades, stabilized their line, and the Confederate attack sputtered to a halt. Later, three Confederate regiments assaulted the Union division on the Springfield Pike but were repulsed and fell back into Perryville. Union troops pursued, and skirmishing occurred in the streets until dark. By that time, Union reinforcements were threatening the Confederate left flank. Bragg, short of men and supplies, withdrew during the night, and continued the Confederate retreat by way of Cumberland Gap into East Tennessee.[6]

Considering the casualties related to the engaged strengths of the armies,[2] the Battle of Perryville was one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War. It was the largest battle fought in the state of Kentucky.[7]

Opposing viewpoints within the state vied for control during the early part of the war, and the state legislature declared official neutrality between the combatants. This neutrality was first violated on September 3, 1861, when Confederate Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk occupied Columbus, considered key to controlling the Lower Mississippi. Two days later Union Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant seized Paducah. Henceforth, neither adversary respected the proclaimed neutrality of the state.[10] While the state never seceded from the Union, Confederate sympathizers who were members of the legislature set up a temporary Confederate capital in Bowling Green in November 1861. The Confederate States recognized Kentucky and added a star representing the state to the Confederate flag.[11]

The initiative to invade Kentucky came primarily from Confederate Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of the Department of East Tennessee. He believed the campaign would allow them to obtain supplies, enlist recruits, divert Union troops from Tennessee, and claim Kentucky for the Confederacy. In July 1862 Col. John Hunt Morgan carried out a successful cavalry raid in the state, venturing deeply into the rear areas of Buell’s department. The raid caused considerable consternation in Buell’s command and in Washington, D.C. During the raid, Morgan and his forces were cheered and supported by many residents. He added 300 Kentucky volunteers to his 900-man force during the raid. He confidently promised Kirby Smith, “The whole country can be secured, and 25,000 or 30,000 men will join you at once.”[12]

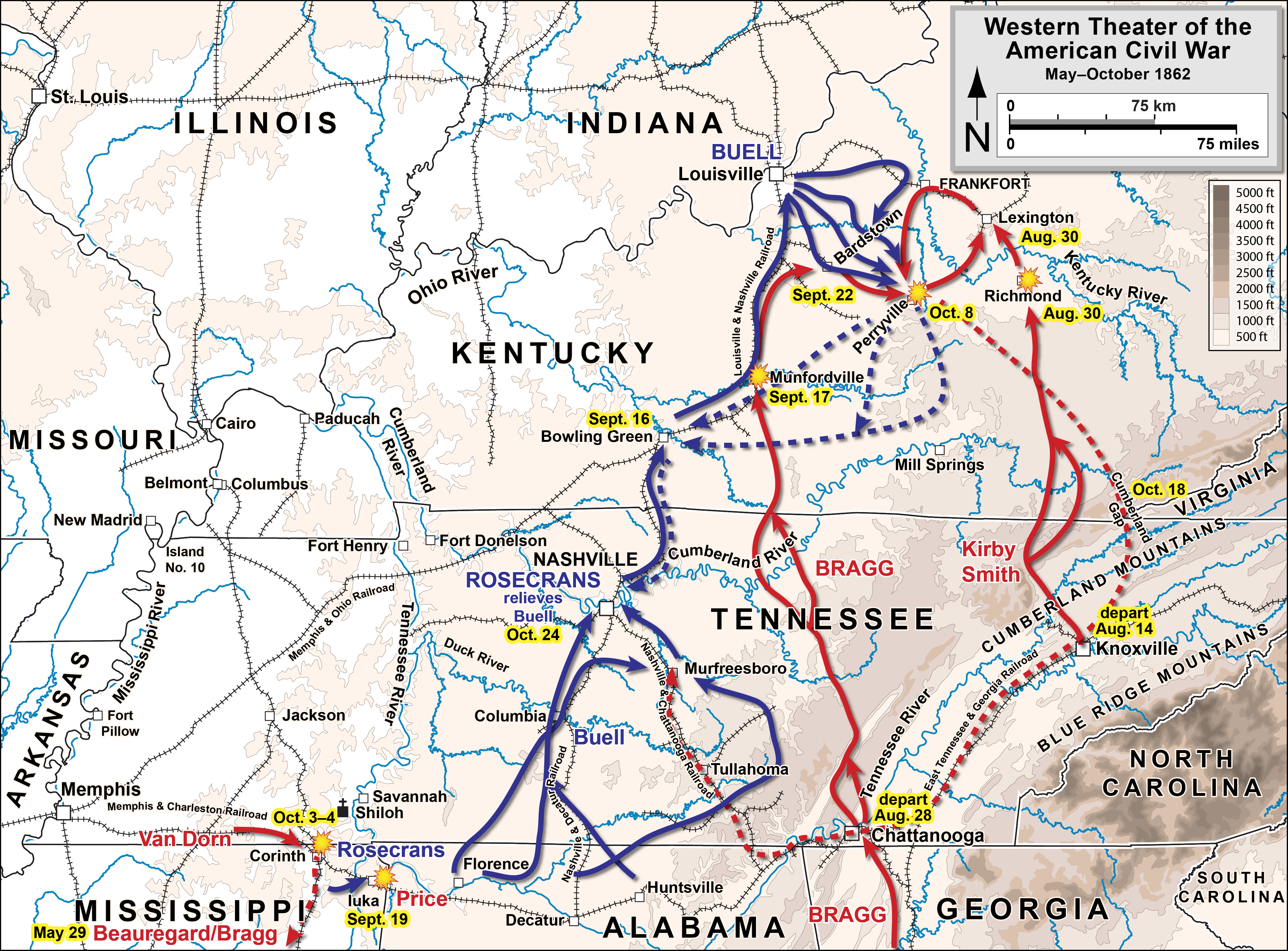

Bragg considered various options, including an attempt to retake Corinth, Mississippi, or to advance against Buell’s army through Middle Tennessee. He eventually heeded Kirby Smith’s calls for reinforcement and decided to relocate his Army of Mississippi to join with him. He moved 30,000 infantrymen in a tortuous railroad journey from Tupelo, Mississippi, through Mobile and Montgomery to Chattanooga. Supply wagons, cavalry, and artillery moved overland under their own power through Rome, Georgia. Although Bragg was the senior general in the theater, Confederate President Jefferson Davis had established Kirby Smith’s Department of East Tennessee as an independent command, reporting directly to Richmond. This decision caused Bragg difficulty during the campaign.[13]

Smith and Bragg met in Chattanooga on July 31, 1862, and devised a plan for the campaign: The newly created Army of Kentucky, including two of Bragg’s brigades and approximately 21,000 men, would march north under Kirby Smith’s command into Kentucky to dispose of the Union defenders of Cumberland Gap. (Bragg’s army was too exhausted from its long journey to begin immediate offensive operations.) Smith would return to join Bragg, and their combined forces would attempt to maneuver into Buell’s rear and force a battle to protect his supply lines. Any attempt by Ulysses S. Grant to reinforce Buell from northern Mississippi would be handled by the two small armies of Maj. Gens. Sterling Price and Earl Van Dorn. Once the armies were combined, Bragg’s seniority would apply and Smith would be under his direct command. Assuming that Buell’s army could be destroyed, Bragg and Smith would march north into Kentucky, a movement they assumed would be welcomed by the local populace. Any remaining Federal force would be defeated in a grand battle in Kentucky, establishing the Confederate frontier at the Ohio River.[14]

The campaign plan was bold but risky, requiring perfect coordination between multiple armies that would initially have no unity of command. Bragg almost immediately began to have second thoughts, despite pressure from President Davis to take Kentucky. Smith quickly abandoned the agreement, foreseeing that a solo adventure in Kentucky would bring him personal glory. He deceived Bragg as to his intentions and requested two additional brigades, ostensibly for his expedition to Cumberland Gap.[15] On August 9, Smith informed Bragg that he was breaking the agreement and intended to bypass Cumberland Gap, leaving a small holding force to neutralize the Union garrison, and to move north. Unable to command Smith to honor their plan, Bragg focused on a movement to Lexington instead of Nashville. He cautioned Smith that Buell could pursue and defeat his smaller army before Bragg’s army could join up with them.[16]

Smith marched north with 21,000 men from Knoxville on August 13; Bragg departed from Chattanooga on August 27, just before Smith reached Lexington.[17] The beginning of the campaign coincided with Gen. Robert E. Lee’s offensive in the Northern Virginia Campaign (Second Manassas Campaign) and with Price’s and Van Dorn’s operations against Grant. Although not centrally directed, it was the largest simultaneous Confederate offensive of the war.[18]

Meanwhile, Buell was forced to abandon his slow advance toward Chattanooga. Receiving word of the Confederate movements, he decided to concentrate his army around Nashville. The news that Smith and Bragg were both in Kentucky convinced him of the need to place his army between the Confederates and the Union cities of Louisville and Cincinnati. On September 7, Buell’s Army of the Ohio left Nashville and began racing Bragg to Louisville.[19]

On the way, Bragg was distracted by the capture of a Union fort at Munfordville. He had to decide whether to continue toward a fight with Buell (over Louisville) or rejoin Smith, who had gained control of the center of the state by capturing Richmond and Lexington, and threatened to move on Cincinnati. Bragg chose to rejoin Smith. Buell reached Louisville, where he gathered, reorganized, and reinforced his army with thousands of new recruits. He dispatched 20,000 men under Brig. Gen. Joshua W. Sill toward Frankfort, hoping to distract Smith and prevent the two Confederate armies from joining against him. Meanwhile, Bragg left his army and met Smith in Frankfort, where they attended the inauguration of Confederate Governor Richard Hawes on October 4. The inauguration ceremony was disrupted by the sound of cannon fire from Sill’s approaching division, and organizers canceled the inaugural ball scheduled for that evening.[20]

On October 1, Buell’s Army of the Ohio left Louisville with Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas as his second in command. (Two days earlier, Buell had received orders from Washington relieving him of command, to be replaced by Thomas. Thomas demurred, refusing to accept command while the campaign was underway, leaving Buell in place.) The 55,000 troops—many of whom Thomas described as “as yet undisciplined, unprovided with suitable artillery, and in every way unfit for active operations against a disciplined foe”[21]—advanced toward Bragg’s veteran army in Bardstown on three separate roads.[22]

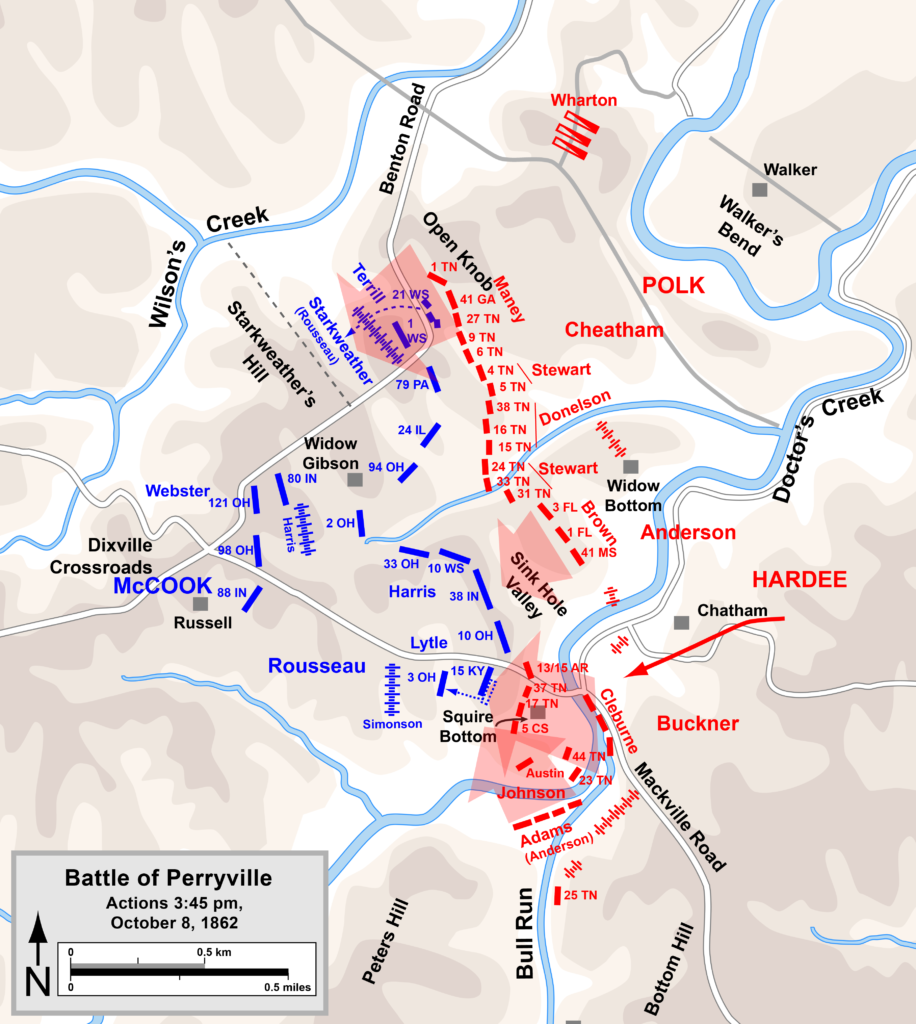

The I Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Alexander M. McCook, marched on the left, along the Mackville Road. His 13,000 men consisted of the 3rd Division, under Brig. Gen. Lovell H. Rousseau, and the 10th Division, under Brig. Gen. James S. Jackson.[23]

The II Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden, marched on the right, along the Lebanon Road. His 20,000 men were in three divisions: the 4th, commanded by Brig. Gen. William Sooy Smith; the 5th, Brig. Gen. Horatio P. Van Cleve; and the 6th, Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood.[24]

The III Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Charles Champion Gilbert, took the center, along the Springfield Pike. Just a few weeks earlier, Gilbert had been a captain, but was elevated to acting major general and corps command following the death by murder of the previous commander, Maj. Gen. William “Bull” Nelson. Gilbert’s 22,000 men were also in three divisions: the 1st, under Brig. Gen. Albin F. Schoepf; 9th, Brig. Gen. Robert B. Mitchell; and the 11th, Brig. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan.[25]

Bragg’s Army of Mississippi consisted of about 16,800 men in two wings. The Right Wing, commanded by Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk, consisted of a single division under Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham. The Left Wing, commanded by Maj. Gen. William J. Hardee, consisted of the divisions of Brig. Gen. J. Patton Anderson and Maj. Gen. Simon B. Buckner.[26]

When he departed for Frankfort on September 28, Bragg left his army under Polk’s command. On October 3, the approach of the large Union force caused the Confederates to withdraw eastward and Bardstown was occupied on October 4. Hardee’s wing stopped at Perryville and requested reinforcements from Bragg. Although Bragg wished to concentrate his army at Versailles, the quickly approaching Federal III Corps forced the concentration at Perryville and Harrodsburg.[27]

Hardee had selected Perryville for a few reasons. The village of approximately 300 residents had an excellent road network with connections to nearby towns in six directions, allowing for strategic flexibility. It was located to prevent the Federals from reaching the Confederate supply depot in Bryantsville. Finally, it was a potential source of water. The area had been afflicted by a drought for months. The heat was oppressive for both men and horses, and the few sources of drinking water provided by the rivers and creeks west of town—most reduced to isolated stagnant puddles—were desperately sought after.[28]

On October 7, Buell reached the Perryville area as Union cavalry clashed with Wheeler’s rearguard throughout the day.[29] Accompanying III Corps, Buell learned that the Confederates had halted at Perryville and were deploying their infantry. He therefore planned an attack. The enemy force was his principal objective, but the availability of water also made control of the town and surrounding area desirable. Buell issued orders for all corps to move at 3 a.m. the next day and attack at 10 a.m. However, movements of the I and II Corps were delayed, having deviated several miles from their line of march in search of water. Buell decided to delay his attack until October 9 to complete his army’s deployment and ordered each corps commander to avoid a general engagement on October 8. Buell was unable to oversee the deployment of his arriving corps. Thrown from his horse, he suffered injuries that prevented him from riding. He established his headquarters at the Dorsey house, about 3 miles (4.8 km) due west of town.[30]

Hardee established a line of defense across the three roads leading into Perryville from the north and west. Until reinforcements could arrive, he was limited to three of the four brigades of Buckner’s division. Brig. Gen. Sterling A. M. Wood was placed at the north of town. Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson was to Wood’s right, east of the Chaplin River near the Harrodsburg Pike. Brig. Gen. St. John R. Liddell’s Arkansas Brigade formed on the crest of Bottom Hill, just east of Bull Run Creek, a tributary of Doctor’s Creek, with one regiment, the 7th Arkansas, sent forward to Peters Hill on the other side of the creek.[31] On the evening of October 7 the final Confederate forces began to arrive. The first of Patton Anderson’s four brigades reached the area around 3 p.m. Brig. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s brigade, the remainder of Buckner’s division, followed. Around midnight, three brigades of Frank Cheatham’s division arrived, moving quickly and enthusiastically, having left their baggage train behind; his fourth brigade, under Brig. Gen. Preston Smith, received orders to return to Harrodsburg.[32]

The first shots of the battle were fired early on the morning of October 8. Finding that there were algae-covered pools of water in the otherwise dry bed of Doctor’s Creek, troops from the 10th Indiana advanced to take advantage of them. They encountered the forward men of the 7th Arkansas and some shots were exchanged. At 2 a.m., Buell and Gilbert, the III Corps commander, ordered newly promoted Brig. Gen. Phil Sheridan to seize Peters Hill; Sheridan started off with the brigade of Col. Daniel McCook (the younger brother of the I Corps commander). Sheridan seized the hill, driving the Arkansans back to the main line of their brigade, but continued to push across the creek. Liddell’s brigade could not check the momentum of Sheridan’s thirsty soldiers and Buckner, Lidell’s division commander, was ordered by Polk not to reinforce him, but to pull his brigade back. Polk was concerned about starting a general engagement to the west of the Chaplin River, fearing he was outnumbered. Meanwhile, on the Union side, a nervous Gilbert ordered Sheridan to return to Peters Hill.[34]

For the preceding few days, Braxton Bragg had been deceived by the diversion launched by Sills against Frankfort, assuming that it was the major thrust of Buell’s army. He wanted Polk to attack and defeat what he considered to be a minor force at Perryville and then immediately return so that the entire army could be joined with Kirby Smith’s. Polk sent a dispatch to Bragg early that morning that he intended to attack vigorously, but he quickly changed his mind and settled on a defensive posture. Bragg, angered that he was not hearing the sounds of battle, rode from Harrodsburg to Perryville to take charge, arriving about 10 a.m. and establishing his headquarters at the Crawford house on the Harrodsburg Pike.[35]

Bragg was appalled at the condition of Polk’s battle line, which contained gaps and was not properly anchored on the flanks. As he rode in, he observed some of McCook’s I Corps troops north of town, but he assumed that the primary threat continued to be on the Springfield Pike, where the action against the III Corps had taken place early that morning. (He had no knowledge of Crittenden’s II Corps approaching on the Lebanon Pike.) He gave orders to realign his army into a north-south line and prepare to attack en echelon. Cheatham’s division marched north from town and prepared to open the attack on the Union left—which Bragg assumed to be on the Mackville Road—beginning a large “left wheel” movement. Two brigades from Patton Anderson’s division would then strike the Union center and Buckner’s division would follow up on the left. Another of Anderson’s brigades, commanded by Col. Samuel Powel,[36] would attack farther to the south along the Springfield Pike. The large clouds of dust raised by Cheatham’s division marching at the double quick north prompted some of McCook’s men to believe the Confederates were starting to retreat, which increased the surprise of the Rebel attack later in the day.[37]

By the afternoon of October 8, most of Buell’s army had arrived. They were positioned with McCook’s I Corps on the left from the Benton Road to the Mackville Road; Gilbert’s III Corps in the center, on the Springfield Pike; Crittenden’s II Corps on the right, along the Lebanon Pike. The vast majority of action during the battle would be against McCook’s corps. Because of an unusual acoustic shadow, few sounds from the battle reached Buell’s headquarters only 2 miles (3.2 km) away; he did not exert effective control over the battle and committed no reserves until late in the day.[38]

Cheatham’s artillery bombardment began at 12:30 p.m., but he did not immediately order his infantry forward. Union troops continued to file into line, extending their flank to the north, beyond the intended avenue of attack. Bragg moved Cheatham’s division into Walker’s Bend, assuming the redirected attack would now strike the Union’s open flank. Unfortunately for the Confederates, their cavalry reconnaissance withdrew before McCook placed an artillery battery under Lt. Charles Parsons and the brigade of Brig. Gen. William R. Terrill onto the Open Knob, a prominent hill on the northern end of the battlefield.[40]

Parsons’ eight guns on the Open Knob were manned by inexperienced soldiers, some of whom were infantry recruits from the 105th Ohio Infantry. Terrill’s 33rd Brigade was posted to defend the guns. Maney’s brigade was able to approach the Knob undetected through the woods, as the Union troops’ attention was focused on Donelson’s attack. Eventually they redirected their guns and a fierce firefight ensued. Brig. Gen. Jackson, the 10th Division commander, was killed in the action, and command fell to Terrill, who immediately made a poor command decision. Obsessed with the safety of his artillery, he ordered the 123rd Illinois to mount a bayonet charge down the hill. The 770 raw Union troops suffered heavy casualties at the hands of the 1,800 veteran Confederates. As reinforcements arrived from the 80th Illinois and a detachment of infantry commanded by Col. Theophilus T. Garrard, the two sides were briefly stalemated. Maney’s artillery, commanded by Lt. William Turner, pounded the inexperienced defenders, and Maney ordered a charge up the steep slope, which swept the Union men from the hill and captured most of Parsons’ guns; the tenacious Parsons had to be dragged away from the scene by his retreating soldiers.[44]

Maney’s attack continued to the west, down the reverse slope of the Open Knob, through a cornfield, and across the Benton Road, after which was another steep ridge, occupied by the 2,200 men in the Union 28th Brigade of Col. John C. Starkweather (Rousseau’s division), and twelve guns. Those guns made the Open Knob an untenable position. Starkweather had placed his 21st Wisconsin in the cornfield about the time that Maney was attacking Parsons’ position. The inexperienced men of the 21st—some of whom had never fired their weapons before, the regiment having been formed less than a month earlier—could see little through the 10- to 12-foot (3.7 m) high cornstalks of the cornfield. They were surprised as the remnants of Terrill’s brigade retreated through their position. As Terrill himself retreated, he shouted, “The Rebels are advancing in terrible force!” Terrill convinced the regimental adjutant to order yet another bayonet charge; 200 men advanced and were quickly smashed by the oncoming Confederates. While the Union men had to hold their fire to keep from shooting their retreating comrades, artillery fire from Starkweather’s batteries caused numerous friendly fire casualties. The 21st managed to fire a volley into the Confederate ranks, but it was answered by a 1,400-musket volley that decimated the Union regiment, and the survivors fled toward the Benton Road.[45]

The guns were discharged so rapidly that it seemed the earth itself was in a volcanic uproar. The iron storm passed through our ranks, mangling and tearing men to pieces. The very air seemed full of stifling smoke and fire, which seemed the very pit of hell, peopled by contending demons.

To fill a gap in the Confederate line where Donelson’s brigade had fought, Cheatham deployed the Tennessee brigade of Brig. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart and they joined Maney’s brigade in the advance against Starkweather. The 1st Tennessee attacked the northern end of the hill while the remainder of Maney’s brigade assaulted directly up the slope. Starkweather’s position was a strong one, however, and the Confederates were initially repulsed by strong infantry and artillery fire. A second charge and vicious hand-to-hand fighting brought the Confederates to the crest, among the batteries. Meanwhile, Brig. Gen. Terrill returned to the fight, leading his troops up the reverse slope of the hill. He was mortally wounded by an artillery shell exploding overhead and died at 2 a.m. the following day. Starkweather meanwhile was able to salvage six of his twelve guns and move them 100 yards (91 m) west to the next ridge. Col. Albert S. Hall began the day as regimental commander of the 105th Ohio, and with the deaths of Jackson, Terrill, and Col. George Webster, advanced all the way to command of the 10th Division by the end of the day.[47]

Once again the Federals had a strong defensive position, with good artillery support and a stone wall at the top of a steep slope. Maney’s and Stewart’s men attempted three assaults, all unsuccessful, and withdrew to the vicinity of the Open Knob at around 5:30 p.m. The assault by Maney’s brigade over three hours was the bloodiest of the battle, and arguably its most crucial action. Historian Kenneth W. Noe describes Maney’s final repulse as the “high-water mark of the Confederacy in the western theater, no less important than the Angle at Gettysburg.”[49]

The en echelon attack continued with Anderson’s division in the center. At about 2:45 p.m., the same time that Maney’s first attack was being repulsed on the Open Knob, the brigade of Col. Thomas M. Jones began its attack across a valley commanded by a large sinkhole. Jones had no orders to attack from Anderson or Hardee, but moved forward on his own initiative when he heard the sound of firing to his right. As they entered the valley, his men were cut down by musketry and fire from twelve artillery pieces on the next ridge, where the Union 9th Brigade (Rousseau’s division) under Col. Leonard A. Harris was posted. Confederate artillery attached to Jones’s brigade, Capt. Charles Lumsden’s Alabama Light Artillery, returned fire, but due to an optical illusion that made two successive ridges look the same, were unable to fix on the appropriate range and their fire had no effect on the Federal line. At 3:30 p.m., the Confederate brigade of Brig. Gen. John C. Brown moved up to take the place of Jones’s retreating men. By this time, most of the Union artillery had had to withdraw to replenish their ammunition, so Brown’s men did not suffer the same fate as Jones’s. Nevertheless, they made no headway against the infantry units in place until successes on the Confederate left put pressure on the Union position.[50]

Almost all of McCook’s I Corps units were posted at the beginning of the battle on land owned by “Squire” Henry P. Bottom. The corps’ right flank, Col. William H. Lytle’s 17th Brigade, was posted on a ridge on which Squire Bottom’s house and barn were situated, overlooking a bend in the Chaplin River and a hill and farm owned by R. F. Chatham on the other side. At about 2:30 p.m. Major John E. Austin’s 14th Battalion of Louisiana Sharpshooters, screening Brig. Gen. Daniel W. Adams‘s Confederate brigade, engaged the 42nd Indiana as it was collecting water in the ravine of Doctor’s Creek. This began a Confederate attack against this area with Brig. Gen. Bushrod R. Johnson’s brigade descending from Chatham House Hill at about 2:45 p.m., crossing the almost-dry riverbed and attacking the 3rd Ohio Infantry, commanded by Col. John Beatty. The attack was disorganized; last-minute changes of orders from Buckner were not distributed to all of the participating units and friendly fire from Confederate artillery broke their lines while still on Chatham House Hill. When the infantry attack eventually moved up the hill, fighting from stone wall to stone wall, Confederate artillery bombarded the 3rd Ohio and set afire Squire Bottom’s log barn. Some of the Union wounded soldiers had sought refuge in the barn and many were burned to death.[51]

The Ohioans withdrew and were replaced in their position by the 15th Kentucky. As Johnson’s men ran low on ammunition, Brig. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne’s brigade entered the battle at about 3:40 p.m. Cleburne’s horse, Dixie, was killed by an artillery shell, which also wounded Cleburne in the ankle, but he kept his troops moving forward. As they advanced up the slope, they were subjected to Confederate artillery fire; Cleburne later surmised that the friendly fire was caused by his men wearing blue uniform trousers, which had been captured from Union soldiers at Richmond. On Cleburne’s left, Brig. Gen. Daniel W. Adams‘s brigade joined the attack against the 15th Kentucky, which had been reinforced by three companies of the 3rd Ohio. The Union troops retreated to the west toward the Russell House, McCook’s headquarters. Lytle was wounded in the head as he attempted to rally his men. He was left on the field for dead, and was captured.[52]

What soldier under Buell will forget the horrible affair at Perryville, where 30,000 men stood idly by to see and hear the needless slaughter in McCook’s unaided, neglected and even abandoned command, without firing a shot or moving a step in its relief?

While Lytle’s brigade was being beaten back, the left flank of Phil Sheridan’s division was only a few hundred yards to the south on Peters Hill. One of the lingering controversies of the battle has been why he did not choose to join the fight. Earlier in the day he had been ordered by Gilbert not to bring on a general engagement. At around 2 p.m., the sound of artillery fire reached army headquarters where Buell was having dinner with Gilbert; the two generals assumed that it was Union artillery practicing and sent word to Sheridan not to waste gunpowder. Sheridan did project some artillery fire into the Confederate assault, but when Gilbert finally arrived from the rear, he feared that Sheridan would be attacked and ordered him back to his entrenchments.[54]

Sheridan’s division did participate toward the end of the battle. The Confederate brigade of Col. Samuel Powel (Anderson’s division) was ordered to advance in conjunction with Adams’s brigade, on Cleburne’s left. The two brigades were widely separated, however, with Powel’s on Edwards House Hill, immediately west of Perryville. At about 4 p.m., Powel received orders from Bragg to advance west on the Springfield Pike to silence the battery of Capt. Henry Hescock, which was firing into the left flank of Bragg’s assault. Bragg assumed this was an isolated battery, not the entire III Corps. Three regiments of Powel’s brigade encountered Sheridan’s division, and although Sheridan was initially concerned by the Confederates’ aggressive attack and sent for reinforcements, the three regiments were quickly repulsed.[56]

It was like running a marathon, over fences and ditches and cornfields, the enemy ahead and we in pursuit. At times, we were so close that I was once able to give a Rebel a kick in the rear.

Sheridan, who would be characterized in later battles as very aggressive, hesitated to pursue the smaller force, and also refused a request by Daniel McCook to move north in support of his brother’s corps. However, his earlier request for reinforcements bore fruit and the 31st Brigade of Col. William P. Carlin (Mitchell’s division) moved up on Sheridan’s right. Carlin’s men moved aggressively in pursuit of Powel, chasing them as fast as they could run toward Perryville. As they reached the cemetery on the western outskirts of town, fierce artillery dueling commenced. Carlin pressed forward and was joined by the 21st Brigade of Col. George D. Wagner (Wood’s division, II Corps). They were poised to capture the town and the critical crossroads that dominated Braxton Bragg’s avenue of withdrawal, but an order from Gilbert to Mitchell curtailed the advance, despite Mitchell’s furious protestations.[58]

Bragg’s attack had been a large pincer movement, forcing both flanks of McCook’s corps back into a concentrated mass. This mass occurred at the Dixville Crossroads, where the Benton Road crossed the Mackville Road. If this intersection could be seized, the Confederates could conceivably get around the right wing of McCook’s corps, effectively cutting them off from the rest of the army. The southern jaw of the pincer began to slow at the temporary line established at the Russell House. Harris’s and Lytle’s brigades defended until Cleburne’s and Adams’s attack ground to a halt. The northern jaw had been stopped by Starkweather’s defense. The remaining attacks came from north of the Mackville Road, by two fresh brigades from Buckner’s division: Brig. Gen. St. John R. Liddell’s and Brig. Gen. Sterling A. M. Wood’s.[60]

The initial target of the assault was Col. George Webster’s 34th Brigade of Jackson’s division. Webster was mortally wounded during the fighting. His death marked the final senior loss for the 10th Division—the division commander, Jackson, and the other brigade commander, Terrill, had also been mortally wounded. (The previous evening, Jackson, Terrill, and Webster had been idly discussing the possibility of all of them being killed in battle and they dismissed the thought as being mathematically negligible.) Webster’s infantry and Capt. Harris’s artillery battery posted on a hill near the Benton Road shot Wood’s attackers to pieces and they were forced to fall back. They regrouped at the base of the hill and renewed their assault. Harris’s battery ran low on ammunition and had to withdraw, and the Confederate attack pushed Webster’s men back toward the crossroads. Col. Michael Gooding’s 13th Brigade (Mitchell’s division) arrived on the field from Gilbert’s corps and took up the fight. Wood’s men withdrew and were replaced by Liddell’s.[61]

The arrival of reinforcements was a result of McCook’s belated attempts to secure aid for his beleaguered corps. At 2:30 p.m. he sent an aide to Sheridan on Peters Hill, requesting that he secure I Corps’ right flank. McCook dispatched a second staff officer at 3 p.m. to obtain assistance from the nearest III Corps unit. The officer encountered Brig. Gen. Albin F. Schoepf, commanding the 1st Division, the III Corps’ reserve. Unwilling to act on his own authority, Schoepf referred the staff officer to Gilbert, who in turn referred him to Buell’s headquarters more than 2 miles (3.2 km) away. The arrival of McCook’s staff officer at about 4 p.m. surprised the army commander, who had heard little battle noise and found it difficult to believe that a major Confederate attack had been under way for some time. Nevertheless, Buell ordered two brigades from Schoepf’s division to support I Corps. This relatively minor commitment indicated Buell’s unwillingness to accept the reported dire situation at face value.[62]

Liddell’s men fired at an unknown unit less than 100 yards (91 m) east of the crossroads. Calls were heard, “You are firing upon friends; for God’s sake stop!” Leonidas Polk, the wing commander, decided to ride forward to see who had been the victims of the supposedly friendly fire. Polk found that he had ridden by mistake into the lines of the 22nd Indiana and was forced to bluff his way out by riding down the Union line, pretending to be a Union officer, and shouting at the Federal troops to cease fire. When he had escaped, he shouted to Liddell, and the Confederates fired, hundreds of muskets in a single volley, which killed Col. Squire Keith and caused casualties of 65% in the 22nd Indiana, the highest percentage of any regiment engaged at Perryville. Although Liddell wanted to pursue the assault, Polk had been unnerved by his personal contact with the enemy and halted the attack, blaming the falling darkness. The Union units moved their supplies and equipment through the endangered intersection and consolidated their lines on a chain of hills 200 yards (180 m) northwest. McCook’s corps had been badly damaged during the day, but was not destroyed.[63]

I was in every battle, skirmish and march that was made by the First Tennessee Regiment during the war, and I do not remember of a harder contest and more evenly fought battle than that of Perryville. If it had been two men wrestling, it would have been called a “dog fall.” Both sides claim victory—both whipped.

Union casualties totaled 4,276 (894 killed, 2,911 wounded, 471 captured or missing). Confederate casualties were 3,401 (532 killed, 2,641 wounded, 228 captured or missing).[65] In all, casualties totaled one-fifth of those involved.

Braxton Bragg had arguably won a tactical victory, having fought aggressively and pushed his opponent back for over a mile. But his precarious strategic situation became clear to him as he found out about the III Corps advance on the Springfield Pike, and when he learned late in the day of the II Corps’ presence on the Lebanon Pike. At 9 p.m. he met with his subordinates at the Crawford House and gave orders to begin a withdrawal after midnight, leaving a picket line in place while his army joined up with Kirby Smith’s. As the army marched toward Harrodsburg, they were forced to leave 900 wounded men behind.[66]

The two other corps of Buell’s army were each as large as the entire Confederate force engaged. Had they both advanced boldly once the battle was underway, they could have seized the town of Perryville, cut off the attackers from their supply depots in central Kentucky, and very possibly achieved a decisive battlefield victory on the model of Austerlitz or Waterloo.

Bragg united his forces with Smith’s at Harrodsburg, and the Union and Confederate armies, now of comparable size, skirmished with one another over the next week or so, but neither attacked. Bragg soon realized that the new infantry recruits he had sought from Kentucky would not be forthcoming, though many were willing to join the cavalry, and that he lacked the logistical support he needed to remain in the state. He made his way southeast to Knoxville, Tennessee, through the Cumberland Gap. Bragg was quickly called to the Confederate capital, Richmond, Virginia, to explain to Jefferson Davis the charges brought by his officers about how he had conducted his campaign, who were demanding that he be replaced as head of the army. Although Davis decided to leave the general in command, Bragg’s relationship with his subordinates would be severely damaged. Upon rejoining the army, he ordered a movement to Murfreesboro, Tennessee.[68]

Buell conducted a half-hearted pursuit of Bragg and returned to Nashville, rather than pushing on to East Tennessee as the Lincoln administration had wished. Pent-up dissatisfaction with Buell’s performance resulted in a reorganization of the Western departments. On October 24, a new Department of the Cumberland was formed under Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, and Buell’s Army of the Ohio was assigned to it, redesignated the XIV Corps. (After the Battle of Stones River at Murfreesboro in late December, another strategic defeat for Braxton Bragg, it would receive its more familiar name, the Army of the Cumberland.) Buell was ordered to appear before a commission investigating his conduct during the campaign. He remained in military limbo for a year and a half, his career essentially ruined. He resigned from the service in May 1864.[69]

Following the Battle of Perryville, the Union maintained control of Kentucky for the rest of the war. Historian James M. McPherson considers Perryville to be part of a great turning point of the war, “when battles at Antietam and Perryville threw back Confederate invasions, forestalled European mediation and recognition of the Confederacy, perhaps prevented a Democratic victory in the northern elections of 1862 that might have inhibited the government’s ability to carry on the war, and set the stage for the Emancipation Proclamation which enlarged the scope and purpose of the conflict.”[70]

Portions of the battlefield of Perryville are preserved by the state of Kentucky as Perryville Battlefield State Historic Site.