About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

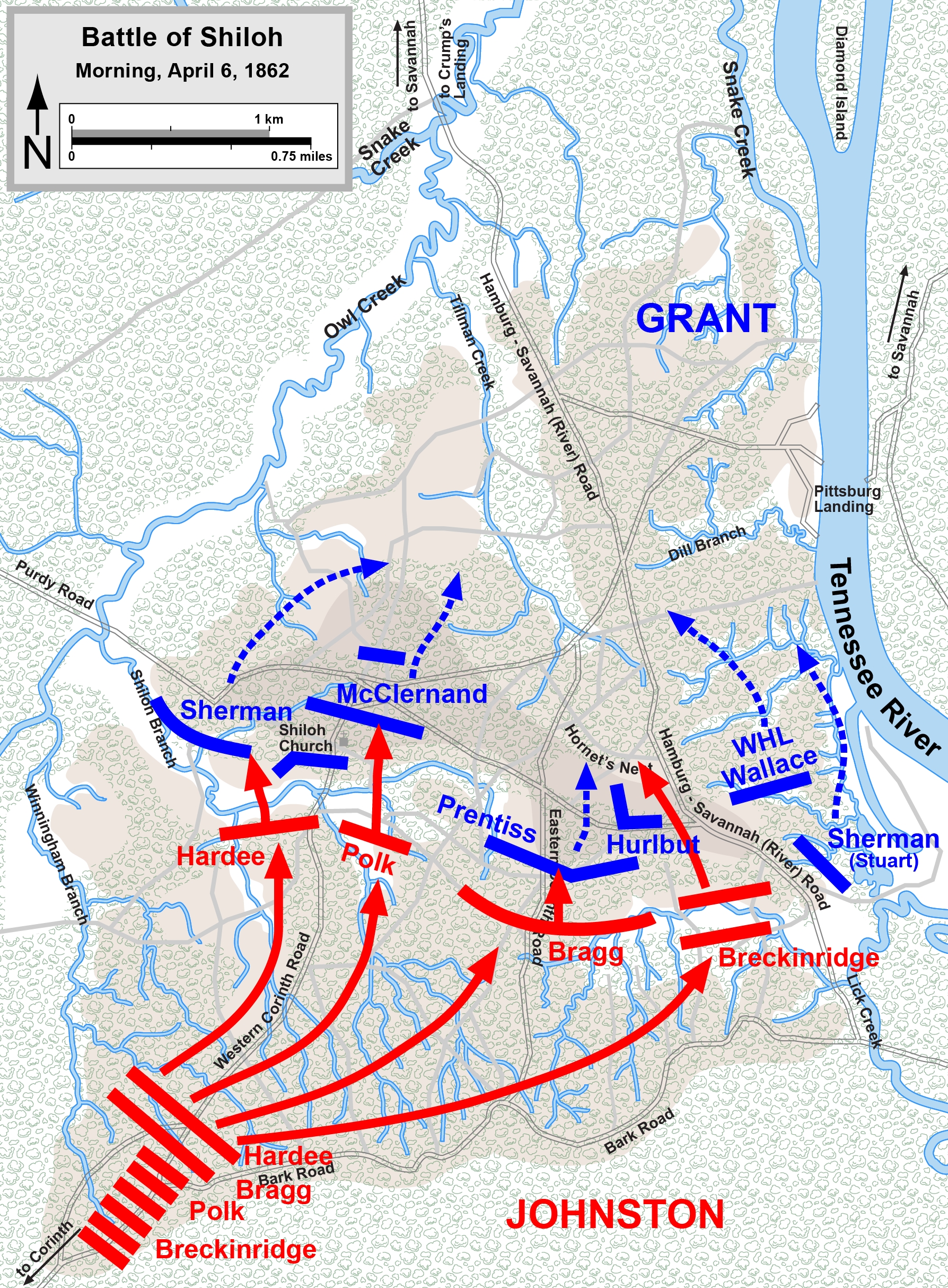

The Battle of Shiloh also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, was a major battle in the Western Theater of the American Civil War, fought April 6 – 7, 1862, in southwestern Tennessee. A Union army under Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had moved via the Tennessee River deep into Tennessee and was encamped principally at Pittsburg Landing on the west bank of the river. Confederate forces under Generals Albert Sidney Johnston and P. G. T. Beauregard launched a surprise attack on Grant there. The Confederates achieved considerable success on the first day, but were ultimately defeated on the second day. On the first day of the battle, the Confederates struck with the intention of driving the Union defenders away from the river and into the swamps of Owl Creek to the west, hoping to defeat Grant’s Army of the Tennessee before the anticipated arrival of Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio. The Confederate battle lines became confused during the fierce fighting, and Grant’s men instead fell back to the northeast, in the direction of Pittsburg Landing. A position on a slightly sunken road, nicknamed the “Hornet’s Nest”, defended by the men of Brig. Gens. Benjamin M. Prentiss’s and W. H. L. Wallace’s divisions, provided critical time for the rest of the Union line to stabilize under the protection of numerous artillery batteries. Gen. Johnston was killed during the first day of fighting, and Beauregard, his second in command, decided against assaulting the final Union position that night.

Reinforcements from Gen. Buell and from Grant’s own army arrived in the evening and turned the tide the next morning, when the Union commanders launched a counterattack along the entire line. The Confederates were forced to retreat from the bloodiest battle in United States history up to that time, ending their hopes that they could block the Union advance into northern Mississippi.

After the losses of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson in February 1862, Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston withdrew his forces into western Tennessee, northern Mississippi, and Alabama to reorganize. In early March, Union Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, then commander of the Department of the Missouri, responded by ordering Grant to advance his Army of West Tennessee (soon to be known by its more famous name, the Army of the Tennessee) on an invasion up the Tennessee River. Halleck then ordered Grant to remain at Fort Henry and turn field command of the expedition over to a subordinate, C.F. Smith, just nominated as a major general. Various writers assert that Halleck took this step because of professional and personal animosity toward Grant. However, Halleck shortly restored Grant to full command, perhaps influenced by an inquiry from President Abraham Lincoln.[5] By early April, Grant had five divisions at Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee, and a sixth nearby. Meanwhile, Halleck’s command was enlarged and renamed the Department of the Mississippi. Now having command over Buell’s Army of the Ohio, Halleck ordered Buell to concentrate with Grant. Buell duly commenced a march with much of his army from Nashville toward Pittsburg Landing. Halleck intended to take the field in person and lead both armies in an advance south to seize the Memphis & Charleston Railroad, a vital supply line between the Mississippi River Valley, Memphis, and Richmond.[6]

Grant’s army of 48,894 men consisted of six divisions, led by Maj. Gens. John A. McClernand and Lew Wallace, and Brig. Gens. W. H. L. Wallace (replacing Charles Ferguson Smith, disabled by a leg injury), Stephen A. Hurlbut, William T. Sherman, and Benjamin M. Prentiss.[1] By early April, all six of the divisions were encamped on the western side of the Tennessee River, Lew Wallace’s at Crump’s Landing and the rest farther south at Pittsburg Landing. Grant developed a reputation during the war for being more concerned with his own plans than with those of the enemy.[7] His encampment at Pittsburg Landing displayed his most consequential lack of such concern—his army was spread out in bivouac style, many around the small log church named Shiloh (the Hebrew word that means “place of peace”),[8] spending time waiting for Buell with drills for his many raw troops, without entrenchments or other awareness of defensive measures. In his memoirs, Grant reacted to criticism of his lack of entrenchments: “Besides this, the troops with me, officers and men, needed discipline and drill more than they did experience with the pick, shovel and axe. … under all these circumstances I concluded that drill and discipline were worth more to our men than fortifications.”[9] Lew Wallace’s division was 5 miles (8 km) downstream (north) at Crump’s Landing, a position intended to prevent the placement of Confederate river batteries and to strike out at the railroad line at Bethel Station.[10]

On the eve of battle, April 5, the first of Buell’s divisions, under the command of Brig. Gen. William “Bull” Nelson, reached Savannah; Grant instructed Nelson to encamp there rather than cross the river immediately. The rest of Buell’s army was still marching toward Savannah, and only portions of four of his divisions, totaling 17,918 men, would reach the area in time to have any role in the battle, almost entirely on the second day. The other three divisions were led by Brig. Gens. Alexander M. McCook, Thomas L. Crittenden, and Thomas J. Wood, but Wood’s division appeared too late even to be of much service on the second day.[11]

On the Confederate side, Johnston named his newly assembled force the Army of Mississippi.[2] He concentrated almost 55,000 men around Corinth, Mississippi, about 20 miles (30 km) southwest of Grant’s position. Of these, 44,699[1] departed from Corinth on April 3, hoping to surprise Grant before Buell arrived to join forces. They were organized into four large corps, commanded by:

On the eve of battle, Grant’s and Johnston’s armies were of comparable size, but the Confederates were poorly armed with antique weapons, including shotguns, hunting rifles, pistols, flintlock muskets, and even a few pikes. However, some regiments, notably the 6th and 7th Kentucky Infantry, had Enfield rifles.[13] They approached the battle with very little combat experience; Braxton Bragg’s men from Pensacola and Mobile were the best trained. Grant’s army included 32 out of 62 infantry regiments who had combat experience at Fort Donelson. One half of his artillery batteries and most of his cavalry were also combat veterans.[14]

Johnston’s second in command was P. G. T. Beauregard, who urged Johnston not to attack Grant. He was concerned that the sounds of marching and the Confederate soldiers test-firing their rifles after two days of rain had cost them the element of surprise. Johnston refused to accept Beauregard’s advice and told him that he would “attack them if they were a million.” Despite General Beauregard’s well-founded concern, the Union forces did not hear the sounds of the marching army in its approach and remained blissfully unaware of the enemy camped 3 miles (4.8 km) away.[15]

In the struggle tomorrow we shall be fighting men of our own blood, Western men, who understand the use of firearms. The struggle will be a desperate one.

Johnston’s plan was to attack Grant’s left and separate the Union army from its gunboat support (and avenue of retreat) on the Tennessee River, driving it west into the swamps of Snake and Owl Creeks, where it could be destroyed. Johnston’s attack on Grant was originally planned for April 4, but the advance was delayed 48 hours. As a result, Beauregard again feared that the element of surprise had been lost and recommended withdrawing to Corinth. But Johnston once more refused to consider retreat.[17]

At 6:00 a.m. on Sunday, April 6, Johnston’s army was deployed for battle, straddling the Corinth Road. In fact, the army had spent the entire night bivouacking undetected in order of battle just two miles (3 km) away from the Union camps. Their approach and dawn assault achieved almost total strategic and tactical surprise. The Union army had virtually no patrols in place for early warning. Grant telegraphed to Halleck on the night of April 5, “I have scarcely the faintest idea of an attack (general one) being made upon us, but will be prepared should such a thing take place.” Grant’s preparedness proved to be overstated. Sherman, the informal camp commander at Pittsburg Landing, did not believe that the Confederates were anywhere nearby; he discounted any possibility of an attack from the south, expecting that Johnston would eventually attack from the direction of Purdy, Tennessee, to the west. When an Ohio colonel warned Sherman that an attack was imminent, the general said, “Take your damned regiment back to Ohio. There is no enemy nearer than Corinth.” Early that morning Colonel Everett Peabody, commanding Prentiss’s 1st Brigade, had sent forward part of the 25th Missouri Infantry on a reconnaissance, and they engaged Confederate outposts at 5:15 a.m. The spirited fight that ensued did help a little to get Union troops better positioned, but the command of the Union army did not prepare properly.[18]

The confusing alignment of the Confederate troops helped to reduce the effectiveness of the attack since Johnston and Beauregard had no unified battle plan. Johnston had telegraphed Confederate President Jefferson Davis that the attack would proceed as: “Polk the left, Bragg the center, Hardee the right, Breckinridge in reserve.”[19] His strategy was to emphasize the attack on his right flank to prevent the Union Army from reaching the Tennessee River, its supply line and avenue of retreat. He instructed Beauregard to stay in the rear and direct men and supplies as needed, while he rode to the front to lead the men on the battle line. This effectively ceded control of the battle to Beauregard, who had a different concept, simply to attack in three waves and push the Union Army straight eastward into the Tennessee River.[20] The corps of Hardee and Bragg began the assault with their divisions in one line, almost 3 miles (5 km) wide.[21] As these units advanced, they became intermingled and difficult to control. Corps commanders attacked in line without reserves. Artillery could not be concentrated to effect a breakthrough. At about 7:30 a.m. from his position in the rear, Beauregard ordered the corps of Polk and Breckinridge forward on the left and right of the line, diluting their effectiveness. The attack therefore went forward as a frontal assault conducted by a single linear formation, which lacked both the depth and weight needed for success. Command and control in the modern sense were lost from the onset of the first assault.[22]

The assault, despite some shortcomings, was ferocious, and some of the numerous inexperienced Union soldiers of Grant’s new army fled for safety to the Tennessee River. Others fought well but were forced to withdraw under strong pressure and attempted to form new defensive lines. Many regiments fragmented entirely; the companies and sections that remained on the field attached themselves to other commands. During this period, Sherman, who had been so negligent in preparation for the battle, became one of its most important elements. He appeared everywhere along his lines, inspiring his raw recruits to resist the initial assaults despite staggering losses on both sides. He received two minor wounds and had three horses shot out from under him. Historian James M. McPherson cites the battle as the turning point of Sherman’s life, which helped to make him one of the North’s premier generals.[23] Sherman’s division bore the brunt of the initial attack, and despite heavy fire on their position and their right flank crumbling, they fought on stubbornly. The Union troops slowly lost ground and fell back to a position behind Shiloh Church. McClernand’s division temporarily stabilized the position. Overall, however, Johnston’s forces made steady progress until noon, rolling up Union positions one by one.[24] As the Confederates advanced, many threw away their flintlock muskets and grabbed rifles dropped by the fleeing Union troops.[25]

General Grant was about ten miles (16 km) down river at Savannah, Tennessee, that morning. On April 4, he had been injured when his horse fell and pinned him underneath. He was convalescing and unable to move without crutches.[26] He heard the sound of artillery fire and raced to the battlefield by boat, arriving about 8:30 a.m. He worked frantically to bring up reinforcements that seemed near enough to arrive swiftly: Bull Nelson’s division from Savannah and Lew Wallace’s division from Crump’s Landing. However, he would wait almost all day before the first of these reinforcements (from Nelson’s division) arrived. Wallace’s slow movement to the battlefield became particularly controversial.[27]

Wallace’s group had been left as reserves near Crump’s Landing at a place called Stoney Lonesome to the rear of the Union line. At the appearance of the Confederates, Grant sent orders for Wallace to move his unit up to support Sherman. Wallace took a route different from the one Grant intended (claiming later that there was ambiguity to Grant’s order). Wallace arrived at the end of his march to find that Sherman had been forced back and was no longer where Wallace thought he was. Moreover, the battle line had moved so far that Wallace now found himself in the rear of the advancing Southern troops. A messenger arrived with word that Grant was wondering where Wallace was and why he had not arrived at Pittsburg Landing, where the Union was making its stand. Wallace was confused. He felt sure he could viably launch an attack from where he was and hit the Confederates in the rear; after the war he claimed that his division might have attacked and defeated the Confederates if his advance had not been interrupted.[28] Nevertheless, he decided to turn his troops around and march back to Stoney Lonesome. Rather than realign his troops so that the rear guard would be in the front, Wallace chose to march the troops in a circle so that the original order was maintained, only facing in the other direction. Wallace marched back to Stoney Lonesome and then to Pittsburg Landing, arriving at Grant’s position about 6:30 or 7 p.m., when the fighting was practically over. Grant was not pleased, and his endorsement of Wallace’s battle report was negative enough to damage Wallace’s military career severely.[29] Today, Wallace is best remembered not as a soldier, but as the author of Ben-Hur.

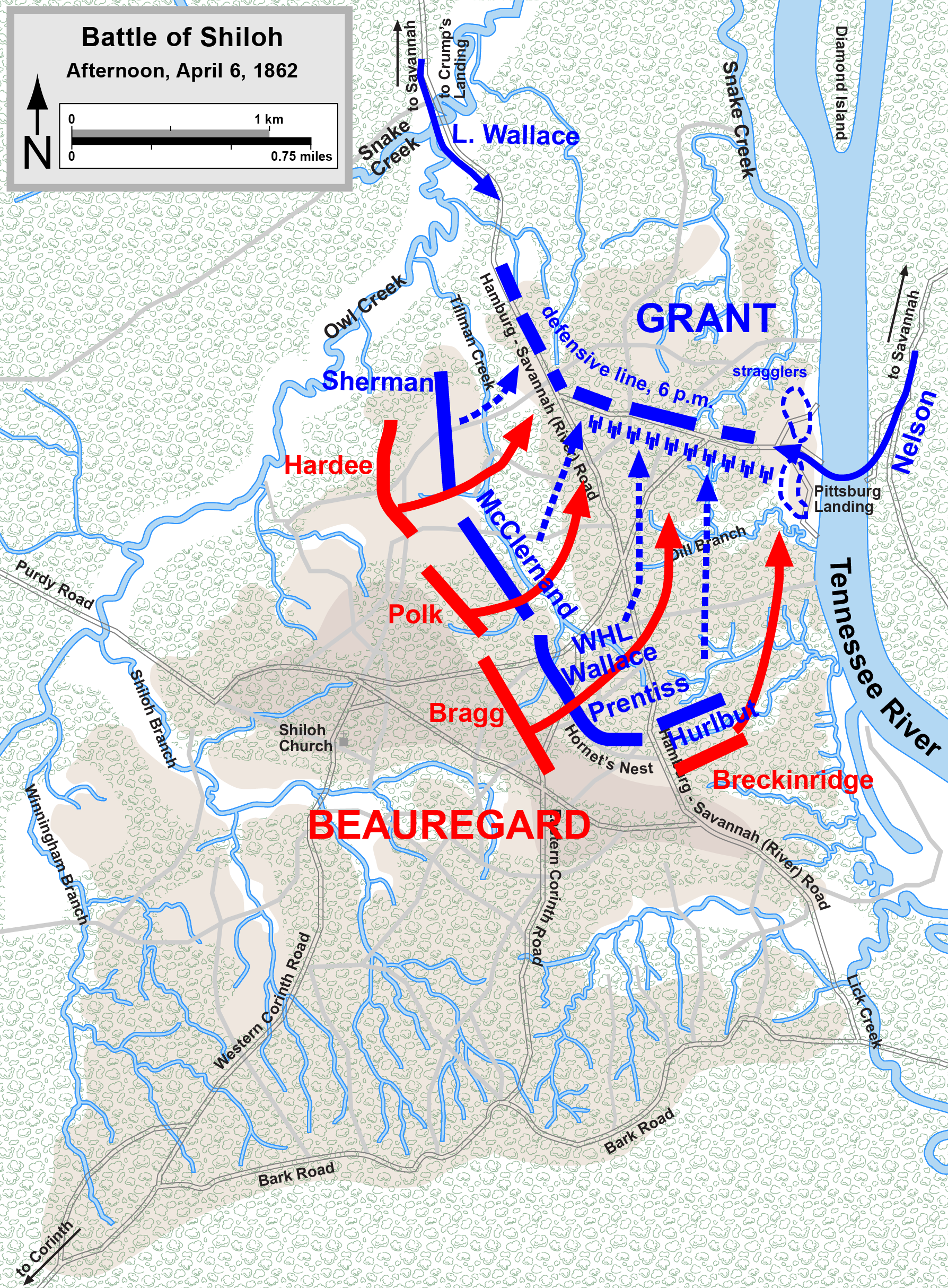

On the main Union defensive line, starting at about 9:00 a.m., men of Prentiss’s and W. H. L. Wallace’s divisions established and held a position nicknamed the Hornet’s Nest, in a field along a road now popularly called the “Sunken Road,” although there is little physical justification for that name.[30] The Confederates assaulted the position for several hours rather than simply bypassing it, and they suffered heavy casualties during these assaults—historians’ estimates of the number of separate charges range from 8 to 14.[31] The Union forces to the left and right of the Nest were forced back, and Prentiss’s position became a salient in the line. Coordination among units in the Nest was poor, and units withdrew based solely on their individual commanders’ decisions. This pressure increased with the mortal wounding of Wallace,[32] who commanded the largest concentration of troops in the position. Regiments became disorganized and companies disintegrated. However, it was not until the Confederates, led by Brig. Gen. Daniel Ruggles, assembled over 50 cannons into “Ruggles’s Battery”[33] to blast the line at close range that they were able to surround the position, and the Hornet’s Nest fell after holding out for seven hours. Surrounded on three sides, General Prentiss surrendered himself and the remains of his division to the Confederates. A large portion of the Union survivors, numbering from 2,200 to 2,400 men, were captured, but their sacrifice bought time for Grant to establish a final defense line near Pittsburg Landing.[34]

While dealing with the Hornet’s Nest, the South suffered a serious setback in the death of their commanding general. Johnston was mortally wounded at about 2:30 p.m. while leading attacks on the Union left through the widow Bell’s cotton field against the Peach Orchard when he was shot in his left leg. Deeming the leg wound to be insignificant, he had sent his personal surgeon away to care for some wounded captured Union soldiers, and in the doctor’s absence, he bled to death within an hour, his boot filling with blood from a severed popliteal artery.[35] This was a significant loss for the Confederacy. Jefferson Davis considered Albert Sidney Johnston to be the most effective general they had (this was two months before Robert E. Lee emerged as the pre-eminent Confederate general). Johnston was the highest-ranking officer from either side to be killed in combat during the Civil War. Beauregard assumed command, but from his position in the rear he may have had only a vague idea of the disposition of forces at the front.[36] He ordered Johnston’s body shrouded for secrecy to avoid damaging morale in the army and then resumed attacks against the Hornet’s Nest. This was likely a tactical error. The Union flanks were slowly pulling back to form a semicircular line around Pittsburg Landing, and if Beauregard had concentrated his forces against the flanks, he might have defeated the Union Army and then reduced the Hornet’s Nest salient at his leisure.[37]

The Union flanks were being pushed back, but not decisively. Hardee and Polk caused Sherman and McClernand on the Union right to retreat in the direction of Pittsburg Landing, leaving the right flank of the Hornet’s Nest exposed. Just after the death of Johnston, Breckinridge, whose corps had been in reserve, attacked on the extreme left of the Union line, driving off the understrength brigade of Colonel David Stuart and potentially opening a path into the Union rear area and the Tennessee River. However, they paused to regroup and recover from exhaustion and disorganization, and then chose to follow the sound of the guns toward the Hornet’s Nest, and an opportunity was lost. After the Hornet’s Nest fell, the remnants of the Union line established a solid three-mile (5 km) front around Pittsburg Landing, extending west from the Tennessee and then north up the River Road, keeping the approach open for the expected belated arrival of Lew Wallace’s division. Sherman commanded the right of the line, McClernand the center, and on the left, remnants of W. H. L. Wallace’s, Hurlbut’s, and Stuart’s men mixed in with the thousands of stragglers[38] who were crowding on the bluff over the landing. One brigade of Buell’s army, Colonel Jacob Ammen’s brigade of Bull Nelson’s division, arrived in time to be ferried over and join the left end of the line.[39] The defensive line included a ring of over 50 cannons[40] and naval guns from the river (the gunboats USS Lexington and USS Tyler).[41] A final Confederate charge of two brigades, led by Brig. Gen. Withers, attempted to break through the line but was repulsed. Beauregard called off a second attempt after 6 p.m., with the sun setting.[42] The Confederate plan had failed; they had pushed Grant east to a defensible position on the river, not forced him west into the swamps.[43]

The evening of April 6 was a dispiriting end to the first day of one of the bloodiest battles in American history. The pitiful cries of wounded and dying men on the fields between the armies could be heard in the Union and Confederate camps throughout the night. A thunderstorm passed through the area and rhythmic shelling from the Union gunboats made the night a miserable experience for both sides. A famous anecdote encapsulates Grant’s unflinching attitude to temporary setbacks and his tendency for offensive action. As the exhausted Confederate soldiers bedded down in the abandoned Union camps, Sherman encountered Grant under a tree, sheltering himself from the pouring rain. He was smoking one of his cigars while considering his losses and planning for the next day. Sherman remarked, “Well, Grant, we’ve had the devil’s own day, haven’t we?” Grant looked up. “Yes,” he replied, followed by a puff. “Yes. Lick ’em tomorrow, though.”[44]

If the enemy comes on us in the morning, we’ll be whipped like hell.

Beauregard sent a telegram to President Davis announcing “A COMPLETE VICTORY” and later admitted, “I thought I had General Grant just where I wanted him and could finish him up in the morning.” Many of his men were jubilant, having overrun the Union camps and taken thousands of prisoners and tons of supplies. But Grant had reason to be optimistic, for Lew Wallace’s division and 15,000 men of Don Carlos Buell’s army began to arrive that evening, with Buell’s men fully on the scene by 4 a.m., in time to turn the tide the next day.[46] Beauregard caused considerable historical controversy with his decision to halt the assault at dusk. Braxton Bragg and Albert Sidney Johnston’s son, Col. William Preston Johnston, were among those who bemoaned the so-called “lost opportunity at Shiloh.” Beauregard did not come to the front to inspect the strength of the Union lines but remained at Shiloh Church. He also discounted intelligence reports from Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest (and bluster from prisoner of war Gen. Prentiss[47]) that Buell’s men were crossing the river to reinforce Grant. In defense of his decision, his troops were simply exhausted, there was less than an hour of daylight left, and Grant’s artillery advantage was formidable. He had also received a dispatch from Brig. Gen. Benjamin Hardin Helm in northern Alabama, indicating that Buell was marching toward Decatur and not Pittsburg Landing.[48]

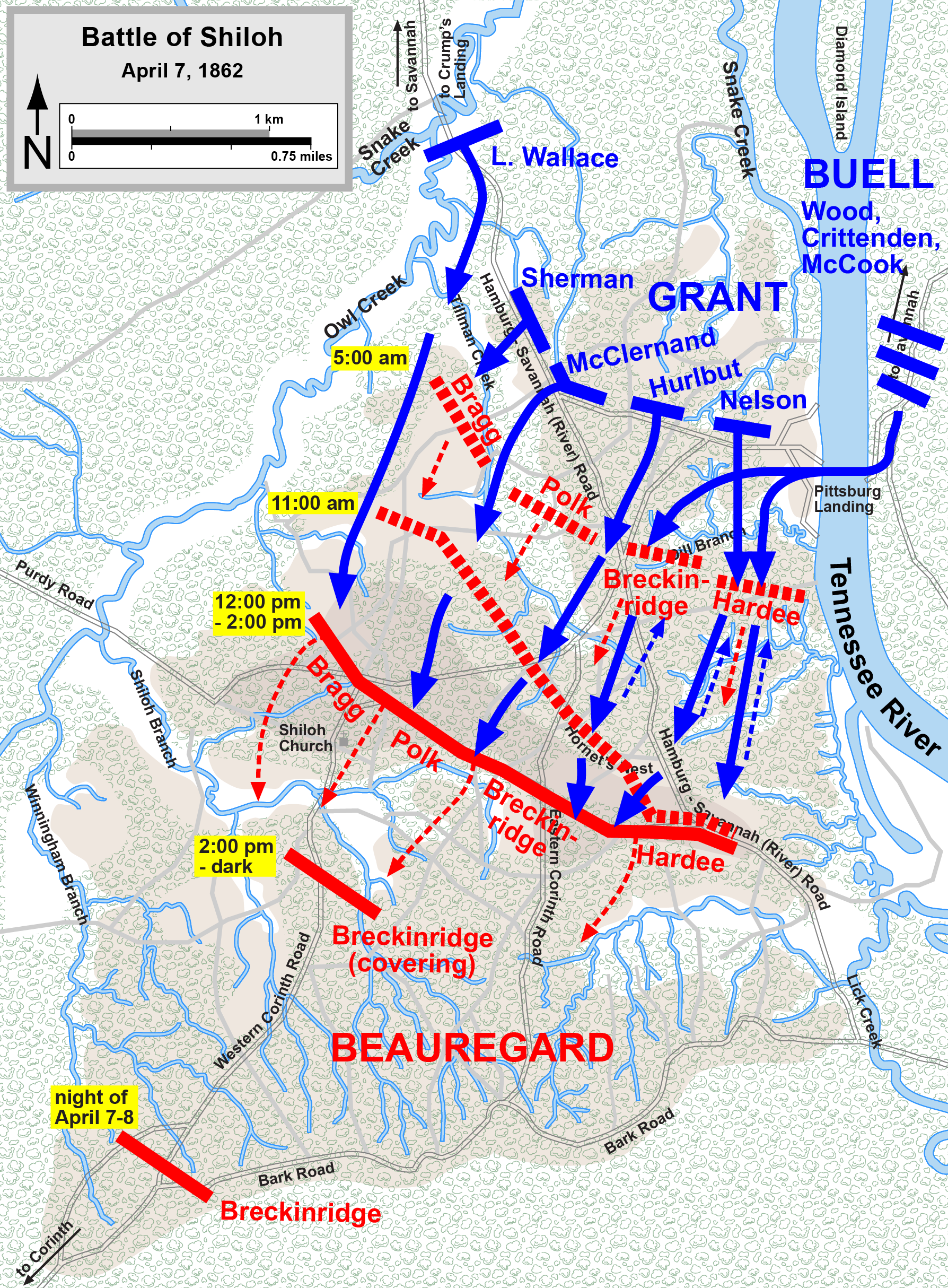

On Monday, April 7, the combined Union armies numbered 45,000 men. The Confederates had suffered as many as 8,500 casualties the first day. Because of straggling and desertion, their commanders reported no more than 20,000 effectives (Buell disputed that figure after the war, stating that there were 28,000). The Confederates had withdrawn south into Prentiss’s and Sherman’s former camps, and Polk’s corps retired all the way to the April 5 Confederate bivouac, 4 miles (6.5 km) southwest of Pittsburg Landing. No line of battle was formed, and few if any commands were resupplied with ammunition. The soldiers were consumed by the need to locate food, water, and shelter for a much-needed night’s rest.[49]

Beauregard, unaware that he was now outnumbered, planned to continue the attack and drive Grant into the river. To his surprise, Union forces started moving forward in a massive counterattack at dawn; Grant and Buell launched their attacks separately; coordination occurred only down at the division level. Lew Wallace’s division was the first to see action, at the extreme right of the Union line, crossing Tilghman Branch around 7 a.m. and driving back the brigade of Col. Preston Pond. On Wallace’s left were the survivors of Sherman’s division, then McClernand’s, and W. H. L. Wallace’s (now under the command of Col. James M. Tuttle). Buell’s divisions continued to the left: Bull Nelson’s, Crittenden’s, and McCook’s. The Confederate defenders were so badly commingled that little unit cohesion existed above the brigade level. It required over two hours to locate Gen. Polk and bring up his division from its bivouac to the southwest. By 10 a.m., Beauregard had stabilized his front with his corps commanders from left to right: Bragg, Polk, Breckinridge, and Hardee.[50] In a thicket near the Hamburg-Purdy Road, the fighting was so intense that Sherman described in his report of the battle “the severest musketry fire I ever heard.”[51]

On the Union left, Nelson’s division led the advance, followed closely by Crittenden’s and McCook’s, down the Corinth and Hamburg-Savannah Roads. After heavy fighting, Crittenden’s division recaptured the Hornet’s Nest area by late morning, but Crittenden and Nelson were both repulsed by determined counterattacks launched by Breckinridge. The Union right made steady progress, driving Bragg and Polk to the south. As Crittenden and McCook resumed their attacks, Breckinridge was forced to retire, and by noon Beauregard’s line paralleled the Hamburg-Purdy Road.[52]

In early afternoon, Beauregard launched a series of counterattacks from the Shiloh Church area, aiming to ensure control of the Corinth Road. The Union right was temporarily driven back by these assaults at Water Oaks Pond. Crittenden, reinforced by Tuttle, seized the road junction of the Hamburg-Purdy and East Corinth Roads, driving the Confederates into Prentiss’s old camps. Nelson resumed his attack and seized the heights overlooking Locust Grove Branch by late afternoon. Beauregard’s final counterattack was flanked and repulsed when Grant moved Col. James C. Veatch’s brigade forward.[53]

Realizing that he had lost the initiative and that he was low on ammunition and food and with over 10,000 of his men killed, wounded, or missing, Beauregard knew he could go no further. He withdrew beyond Shiloh Church, using 5,000 men under Breckinridge as a covering force, massing Confederate batteries at the church and on the ridge south of Shiloh Branch. These forces kept the Union forces in position on the Corinth Road until 5 p.m., when the Confederates began an orderly withdrawal back to Corinth. The exhausted Union soldiers did not pursue much past the original Sherman and Prentiss encampments; Lew Wallace’s division advanced beyond Shiloh Branch but, receiving no support from other units, halted at dark and returned to Sherman’s camp. The battle was over. For long afterwards, Grant and Buell quarreled over Grant’s decision not to mount an immediate pursuit with another hour of daylight remaining. Grant cited the exhaustion of his troops, although the Confederates were certainly just as exhausted. Part of Grant’s reluctance to act could have been the unusual command relationship he had with Buell. Although Grant was the senior officer and technically was in command of both armies, Buell made it quite clear throughout the two days that he was acting independently.[54]

On April 8, Grant sent Sherman south along the Corinth Road on a reconnaissance in force to ascertain if the Confederates had retreated, or if they were regrouping to resume their attacks. Grant’s army lacked the large organized cavalry units that would have been better suited for reconnaissance and for vigorous pursuit of a retreating enemy. Sherman marched with two infantry brigades from his division, along with two battalions of cavalry, and they met up with Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood’s division of Buell’s army. Six miles (10 km) southwest of Pittsburg Landing, Sherman’s men came upon a clear field in which an extensive camp was erected, including a Confederate field hospital, protected by 300 troopers of Confederate cavalry, commanded by Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest. The road approaching the field was covered by fallen trees for over 200 yards (180 m).[55]

As skirmishers from the 77th Ohio Infantry approached, having difficulty clearing the fallen timber, Forrest ordered a charge, producing a wild melee with Confederate troopers firing shotguns and revolvers and brandishing sabers, nearly resulting in the capture of Sherman. As Col. Jesse Hildebrand’s brigade began forming in line of battle, the Southern troopers started to retreat at the sight of the strong force, and Forrest, who was well in advance of his men, came within a few yards of the Union soldiers before realizing he was all alone. Sherman’s men yelled out, “Kill him! Kill him and his horse!” A Union soldier shoved his musket into Forrest’s side and fired, striking him above the hip, penetrating to near the spine. Although he was seriously wounded, Forrest was able to stay on horseback and escape; he survived both the wound and the war. The Union lost about 100 men, mostly captured during Forrest’s charge, in an incident that has been remembered with the name “Fallen Timbers”. After capturing the Confederate field hospital, Sherman encountered the rear of Breckinridge’s covering force and, determining that the enemy was making no signs of renewing its attack, withdrew back to camp.[56]

In the immediate aftermath of the battle, Northern newspapers vilified Grant for his performance during the battle on April 6. Reporters, many far from the battle, spread the story that Grant had been drunk, falsely alleging that this had resulted in many of his men being bayoneted in their tents because of a lack of defensive preparedness. Despite the Union victory, Grant’s reputation suffered in Northern public opinion. Many credited Buell with taking control of the broken Union forces and leading them to victory on April 7. Calls for Grant’s removal overwhelmed the White House. President Lincoln replied with one of his most famous quotations about Grant: “I can’t spare this man; he fights.” Sherman emerged as an immediate hero, his steadfastness under fire and amid chaos atoning for his previous melancholy and his defensive lapses preceding the battle. Today, however, Grant is recognized positively for the clear judgment he was able to retain under the strenuous circumstances, and his ability to perceive the larger tactical picture that ultimately resulted in victory on the second day.[57]

The two-day battle of Shiloh, the costliest in American history up to that time,[60] resulted in the defeat of the Confederate army and frustration of Johnston’s plans to prevent the joining of the two Union armies in Tennessee. Union casualties were 13,047 (1,754 killed, 8,408 wounded, and 2,885 missing); Grant’s army bore the brunt of the fighting over the two days, with casualties of 1,513 killed, 6,601 wounded, and 2,830 missing or captured. Confederate casualties were 10,699 (1,728 killed, 8,012 wounded, and 959 missing or captured).[61] The dead included the Confederate army’s commander, Albert Sidney Johnston; the highest ranking Union general killed was W. H. L. Wallace. Both sides were shocked at the carnage. None suspected that three more years of such bloodshed remained in the war and that eight larger and bloodier battles were yet to come.[62] Grant came to realize that his prediction of one great battle bringing the war to a close was probably not destined to happen. The war would continue, at great cost in casualties and resources, until the Confederacy succumbed or the Union was divided. Grant also learned a valuable personal lesson on preparedness that (mostly) served him well for the rest of the war.[63]

Shiloh’s importance as a Civil War battle, coupled with the lack of widespread agricultural or industrial development in the area where the battle took place after the war ended, led to its development as one of the first five battlefields restored by the federal government in the 1890s. Government involvement eventually proved insufficient to preserve the sprawling canvas upon which the battle took place. While the federal government had saved just over 2,000 acres at Shiloh by 1897 and consolidated those gains by adding another 1,700 acres by 1954, preservation eventually slowed and gains since 1954 account for only 300 additional acres of saved land.[64]

Private preservation organizations have stepped in to fill this void. The Civil War Trust has been the primary agent of these efforts, preserving 1,154 acres at Shiloh since its inception.[65] The land already preserved by the Trust at Shiloh includes tracts over which Confederate divisions passed as they brought the fight to Ulysses S. Grant’s men on the battle’s first day and land over which those same troops retreated during the Union counteroffensive on day two. A 2012 campaign focused in particular on a section of land which was part of the Confederate right flank on day one and on several tracts which were part of the Battle of Fallen Timbers.[66]