About Publications Library Archives

heritagepost.org

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History

During his daring raid, Morgan and his men captured and paroled about 6,000 Union soldiers and militia, destroyed 34 bridges, disrupted the railroads at more than 60 places, and diverted tens of thousands of troops from other duties. He spread terror throughout the region, and seized thousands of dollars worth of supplies, food, and other items from local stores, houses, and farms.

In Ohio alone, approximately 2,500 horses were stolen and nearly 4,375 homes and businesses were raided. Morgan’s Raid cost Ohio taxpayers nearly $600,000 in damages and over $200,000 in wages paid to the 49,357 Ohioans called up to man 587 companies of local militia.[8]

Morgan’s Raid was a diversionary incursion by Confederate cavalry into the northern (Union) states of Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio and, briefly, West Virginia, during the American Civil War. The raid took place from June 11–July 26, 1863, and is named for the commander of the Confederates, Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan. Although it caused temporary alarm in the North, the raid was ultimately classed as a failure.

The raid covered more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km), beginning in Tennessee and ending in northern Ohio. It coincided with the Vicksburg Campaign and the Gettysburg Campaign, and it was meant to draw U.S. troops away from these fronts by frightening the North into demanding their troops return home. Despite his initial successes, Morgan was thwarted in his attempts to recross the Ohio River and eventually was forced to surrender what remained of his command in northeastern Ohio near the Pennsylvania border. Morgan and other senior officers were kept in the Ohio state penitentiary, but they tunneled their way out and took a train to Cincinnati, where they crossed the Ohio River to safety.

General Morgan and his 2,460 handpicked Confederate cavalrymen, along with 4 artillery pieces,[1] departed from Sparta, Tennessee, on June 11, 1863, intending to divert the attention of the Union Army of the Ohio from Southern forces in the state[2] and possibly stir up pro-southern sentiments in the North. Gen. Braxton Bragg, the regional Confederate commander, had intended for Morgan’s cavalrymen to provide a distraction by entering Kentucky. Morgan, however, confided to some of his officers that he had long desired to invade Indiana and Ohio to bring the terror of war to the North. Bragg had given him carte blanche to ride throughout Tennessee and Kentucky, but ordered him to under no circumstances cross the Ohio River.[3] On June 23, the Federal Army of the Cumberland began its operations against General Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee in what became known as the Tullahoma Campaign, and Morgan decided it was time to move northward into Kentucky.

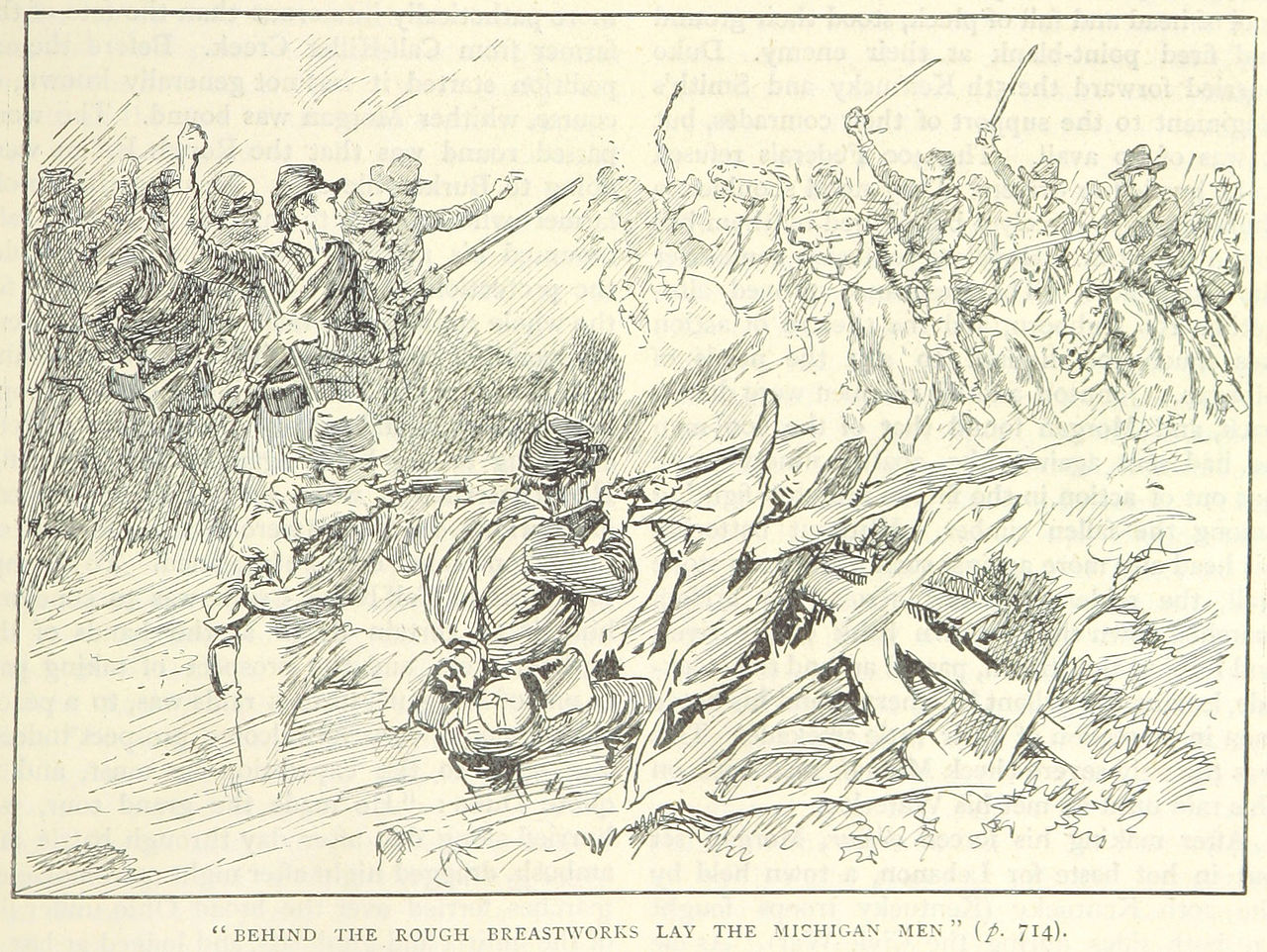

On July 2, hoping to disrupt Union communication lines, Morgan rode into Kentucky, where admiring citizens openly welcomed his cavalrymen. Crossing the rain-swollen Cumberland River at Burkesville, Morgan’s division advanced to the Green River, where it was deflected by half of a Union regiment (the 25th Michigan Infantry) at the Battle of Tebbs Bend on July 4. Morgan soon surprised and captured the garrison at Lebanon. He trapped 400 men from the 20th Kentucky in the town’s railroad depot, but the well-fortified building provided considerable protection. In a sharp six-hour fight, Federal troops killed Morgan’s youngest brother Thomas during the final charge. Morgan finally captured and paroled the Federal troops.

A grieving Morgan continued northward towards Louisville, riding through Springfield, Bardstown, and Garnettsville. Along the way, the Confederates endured several more small skirmishes with Federals and Kentucky home guard units. Just south of the city, however, he turned his remaining men to the northwest and headed for the Ohio River.

At Springfield, Morgan sent a detachment north and east of Louisville, with the intention of confusing Union forces as to where Morgan was really heading. This detachment crossed the Ohio River at Twelve Mile Island, but they were captured near New Pekin, Indiana, before they could rejoin Morgan. To further mislead the Federals on his objectives, Morgan had his telegrapher, “Lightning” Ellsworth, tap telegraph lines and, pretending to be a Union telegrapher, send several messages giving different headings for the raiders and false reports of the size of Morgan’s force—sometimes reporting it as high as 7,000 men. Ellsworth did this throughout the journey, especially in Indiana.[4]

Morgan had sent spy Thomas Hines and a party of 25 Confederates (posing as a Union patrol) on a secret mission into Indiana in June to determine if the local Copperheads would support or join Morgan’s impending raid. After visiting the local Copperhead leader, Dr. William A. Bowles, Hines learned that no desired support would be forthcoming. He and his scouts were soon identified as actually being Confederates, and, in a small skirmish near Leavenworth, Indiana, Hines had to abandon his men as he swam across the Ohio River under gunfire. He wandered around Kentucky for a week seeking information on Morgan’s whereabouts.

By now reduced to 1,800 men, Morgan’s main column had arrived on the morning of July 8 at Brandenburg, Kentucky, a small town along the Ohio River, where Hines rejoined them. Here, the raiders seized two steamboats, the John B. McCombs and the Alice Dean. Morgan, against Bragg’s strict orders,[5] transported his command across the river to Indiana, landing just east of Mauckport. A small company of Indiana home guards contested the crossing with an artillery piece, as did a riverboat carrying a six-pounder. Morgan chased off the local defenders, capturing a sizeable portion as well as their guns. After burning the Alice Dean and sending the John B. McCombs downriver with instructions not to pursue him, Morgan headed away from the river.

Governor Oliver P. Morton worked feverishly to organize Indiana’s defense, calling for able-bodied men to take up arms and form militia companies. Thousands responded and organized themselves into companies and regiments. Col. Lewis Jordan took command of the 450 members of the Harrison County Home Guard (Sixth Regiment, Indiana Legion), consisting of poorly trained civilians with a motley collection of arms. His goal was to delay Morgan long enough for Union reinforcements to arrive.

Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, commander of the Department of the Ohio with headquarters in Cincinnati, quickly organized local Federal troops and home militia to cut off Morgan’s routes back to the South. Morgan headed northward on Mauckport Road, with another brother, Col. Richard Morgan, leading the forward elements. On July 9, one mile south of Corydon, Indiana, the county seat of Harrison County, his advance guard encountered Jordan’s small force, drawn in a battle line behind a hastily thrown up barricade of logs. The colonel attacked, and in a short but spirited battle of less than an hour, he simultaneously outflanked both Union wings, completely routing the hapless militia. Accounts vary as to the number of casualties of the Battle of Corydon, but the most reliable evidence suggests that 4 of Jordan’s men were killed, 10-12 were wounded, and 355 were captured. Morgan counted 11 dead and 40 wounded raiders. Among the dead Federals was the civilian toll keeper who perished near his tollgate. Raiders killed a Lutheran minister, Reverend Peter Glenn, on his farm, 4 miles (6 km) from the battlefield, and stole horses from several other farmers.

General Morgan led his division into Corydon, where he paroled his demoralized prisoners and ransomed the town for cash and supplies. Morgan’s soldiers then traveled east and reached Vienna on July 10, where they burned a railroad bridge and depot, and tapped a telegraph line. After spending the night in Lexington, they headed to the northeast, terrorizing the small towns along the way, including Vernon, Dupont, New Pekin, Salem, and Versailles.

On July 11, while crossing Blue River near New Pekin, Confederate Capt. William J. Davis and some of his men were captured by 73rd Indiana Infantry and a detachment of the 5th U.S. Regulars. Davis and several other soldiers were taken to New Albany and secured in the county jail.

On July 12, Morgan arrived in the town of Dupont, Indiana, where his men burned the town’s storehouse and stole 2,000 smoked hams before riding out of town the next day. The hams were eventually discarded as they began to attract flies, leaving a trail of hams along the side of the road for the pursuing Union Army to follow.

Morgan then headed for Salem where he immediately took possession of the town and placed guards over the stores and streets. His cavalrymen burned the large brick depot, along with all the railcars on the track and the railroad bridges on each side of town. They demanded taxes from area flour and grist mills. After looting stores and taking about $500, they departed in the afternoon.

In Versailles a group of freebooters invaded the local Masonic Lodge, Versailles No. 7, and lifted the Lodge’s badges of office which had originally been made from French silver coins. Morgan, himself a Freemason, ordered the officers’ jewels returned, punishing the thievery of his own men.[6]

Morgan finally left Indiana at Harrison, closely pursued by Federal cavalry.

The Confederates entered Ohio on July 13, destroying bridges, railroads, and government stores. Morgan’s Raid spread alarm across southern and central Ohio, and wild speculation as to his destination. Harper’s Weekly, a leading Northern newspaper, reported:

The raid of the rebel Morgan into Indiana, which he seems to be pursuing with great boldness, has thoroughly aroused the people of that State and of Ohio to a sense of their danger. On 13th General Burnside declared martial law in Cincinnati, and in Covington and Newport on the Kentucky side. All business is suspended until further orders, and all citizens are required to organize in accordance with the direction of the State and municipal authorities. There is nothing definite as to Morgan’s whereabouts; but it is supposed that he will endeavor to move around the city of Cincinnati and cross the river between there and Maysville. The militia is concentrating, in obedience to the order of Governor Tod.

— Harper’s Weekly, July 25, 1863

Sidestepping Burnside’s forces that protected Cincinnati to the south he traveled through such northern communities as Harrison, New Baltimore, Colerain, Springdale, Glendale and Sharonville. Morgan and his men ran into great resistance when trying to capture Camp Dennison. He would eventually retreat and regroup with the other column of his men in Montgomery and bypass Camp Dennison through Wards Corner. Morgan continued east to the Ohio River where, just north of modern Ravenswood, West Virginia, there was a ford at Buffington Island that would allow him to cross over into that state. Burnside correctly guessed Morgan’s intentions. Federal columns under Edward H. Hobson and Henry M. Judah and river gunboats swiftly converged to contest any river crossing. Burnside also sent a militia regiment from Marietta, Ohio, to hold the ford until the Federal forces could arrive. Morgan arrived on the evening of July 18, but decided not to attack the militia in the gathering darkness. It proved to be a mistake.

By morning, the cavalry and gunboats had arrived, blocking Morgan’s escape route. At the subsequent Battle of Buffington Island in Ohio, Union troops won a decisive victory and captured 750 of Morgan’s men, including his brother Richard and noted cavalryman Col. Basil W. Duke. Cut off from safety by the Union gunboats, Morgan and his remaining cavaliers headed northeast back into Ohio. A second attempt at crossing 20 miles (32 km) upriver (opposite Belleville, West Virginia) also failed, with several of Morgan’s men drowning in the swirling river as the gunboats and Union cavalry again drove off the raiders. Col. Adam “Stovepipe” Johnson and over 300 raiders did escape into West Virginia and safety, but General Morgan chose to remain on the Ohio side with the rest of his dwindling force. He was turned away at skirmishes in Gallia County at Coal Hill and Hockingport, losing more of his force.

As Morgan with 400 remaining men headed away from the river into the interior of southern Ohio, he paused at Nelsonville, a small town on the Hocking Canal. His men burned ten wooden canal boats and set a covered bridge ablaze to slow their pursuers. However, as soon as Morgan’s raiders rode off, citizens rushed to save the burning span. Two hours later, Union cavalry arrived, delighted to find that the townspeople had prepared a feast for them.

With his men somewhat rested on Weaver’s homestead near Triadelphia on the 22nd of July, and guided down Island Run by John Weaver who was held hostage, Morgan forded the broad Muskingum River at Eaglesport, just south of Zanesville, before turning northward in Guernsey County. He still hoped to cross the Ohio River at some point and head through West Virginia to safety. At the village of Old Washington, Morgan’s weary men fought a skirmish in the streets before hastily departing, pursued by Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. James M. Shackelford. On July 26, Union forces defeated Morgan at the Battle of Salineville and finally caught him that afternoon near West Point in Columbiana County. They were held in Wellsville, Ohio, then taken to the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus rather than to a prisoner-of-war camp, because of reports that captured Union officers had received similar treatment. Many of his enlisted men ended up in the Camp Douglas stockade in Chicago.

The general and six officers made a daring escape on November 27 by tunneling from an air shaft beneath their cells into the prison yard and scaling the walls.[7] Only two of Morgan’s men were recaptured, and he and the rest soon returned to the South. Morgan was killed less than a year later in Greeneville, Tennessee, by a Union cavalryman after refusing to halt while attempting to escape.

During his daring raid, Morgan and his men captured and paroled about 6,000 Union soldiers and militia, destroyed 34 bridges, disrupted the railroads at more than 60 places, and diverted tens of thousands of troops from other duties. He spread terror throughout the region, and seized thousands of dollars worth of supplies, food, and other items from local stores, houses, and farms. Since the timing somewhat coincided with the Gettysburg Campaign and raids towards Pittsburgh by John D. Imboden’s cavalry, many assumed at the time that Morgan’s Raid was part of a coordinated effort to threaten the Ohio River commerce and spread the war to the North. Few in the North realized that Morgan’s adventure was a violation of his orders and had nothing to do with Robert E. Lee’s simultaneous movement into Pennsylvania.

In Ohio alone, approximately 2,500 horses were stolen and nearly 4,375 homes and businesses were raided. Morgan’s Raid cost Ohio taxpayers nearly $600,000 in damages and over $200,000 in wages paid to the 49,357 Ohioans called up to man 587 companies of local militia.[8]

To Morgan’s men, the long raid had accomplished much, despite their military defeat and high casualties. Col. Basil Duke later wrote, “The objects of the raid were accomplished. General Bragg’s retreat was unmolested by any flanking forces of the enemy, and I think that military men, who will review all the facts, will pronounce that this expedition delayed for weeks the fall of East Tennessee, and prevented the timely reinforcement of Rosecrans by troops that would otherwise have participated in the Battle of Chickamauga.”[9]

To many Confederates, the daring expedition behind enemy lines became known as The Great Raid of 1863, and was initially hailed in the newspapers. However, along with Gettysburg and Vicksburg, it was another in a string of defeats for the Confederate army that summer. Some Northern newspapers derisively labeled Morgan’s expedition as The Calico Raid, in reference to the raiders’ propensity for procuring personal goods from local stores and houses.

Kentucky and Indiana have well-marked John Hunt Morgan Heritage Trails that allow tourists to follow the route of Morgan’s Raid through their states, along with websites and written tour guides.[10] In November 2001, the State of Ohio placed a John Hunt Morgan historical marker on the site of the Ohio State Penitentiary, remembering his imprisonment and daring escape.[7] An equestrian statue of General Morgan was erected and dedicated in 1910 in downtown Lexington, Kentucky.[citation needed] Ohio’s plans for a similar formal trail finally came to fruition in 2013, when the state erected over 600 directional markers and 56 interpretive signs commemorating the route and the important incidents of the raid.[11] Signage was installed during the spring and summer of 2013, in the months leading up to the 150th anniversary of the “Great Raid.”[12]

On the weekend of July 27–28, 2013, communities in Carroll, Jefferson, and Columbiana County, Ohio, held a driving tour to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the raid, with a Civil War era church service, the dedication of a Morgan’s Raid Heritage Trail tablet to mark the location of the fighting at Sharp’s farm, and events in towns on and near the raid route.[13]